I have to say that this is one of my favourite AARs ever. I love the narrative structure you use — it's almost like reading a pop history book, and the constant inclusion of map screenshots is great. Keep up the wonderful work ^_^

A History of the World According to Paradox: A Hands-Off AAR, Part Two

- Thread starter magritte2

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Unlikely, but when they do expect many wars against the locals. A lot of them will come to nothing until the fog clears and the Europeans can start landing in force. Colonizing usually happens once the Americas and Africa are pretty well accounted for.

I'm interested in seeing if its the Huron or Iroquois in control. I find its usually the Huron who win out in most my games.

@dodedo, Oceania has not been reached yet.

@warman, see page 5. The Hurons conquered the Iroquois in 1480.

Thanks again for all the kind comments about my AAR.

@warman, see page 5. The Hurons conquered the Iroquois in 1480.

Thanks again for all the kind comments about my AAR.

Thanks again for all the kind comments about my AAR.

Good job sir! What's your occupation if you don't mind me asking?

I think people overestimate the Hungarians. Their technological backwardness will lead to their utter destruction as soon as they have to fight a real power. The only reason they've gotten so far is because their enemies have been very minor Baltic powers, hardly a challenge for any blob. I think they'll get mixed into a war with Frankfurt or Byzantium or Austria-Navarra and get taught a very brutal lesson. It might even be a chance for Austria to reclaim its homeland.

Or better yet they will get into a war with mega-Byzantines. Then we could have a REAL war after Byzantines are done munching on Hungary.

[badjoke]This AAR *puts on sunglasses* ROCKS

YYYYEEEAAAHHH!!![/badjoke]

I'm sorry, but it was too tempting to not do that.

YYYYEEEAAAHHH!!![/badjoke]

I'm sorry, but it was too tempting to not do that.

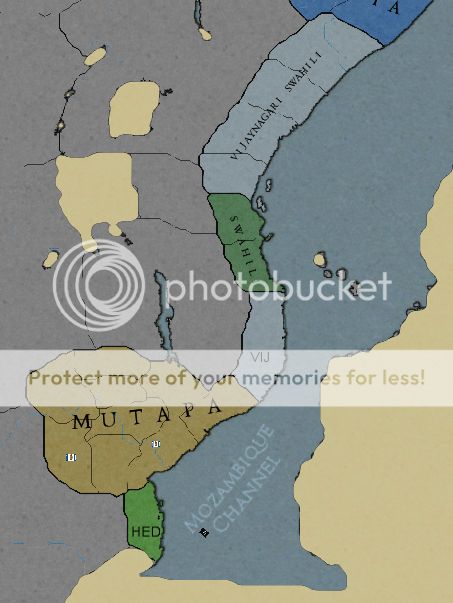

EAST AFRICA, 1650-1681

East Africa was still beset by foreign invaders in the mid-17th century. They had been assailed not only by the Indian powers of Bihar and Vijayanagar, but by Europeans and even the Chinese. Though these newer invaders had failed to grasp a permanent foothold in the region, they had on occasion forced Mutapa to surrender large sums of gold from their rich mines in the interior, most memorably the large payments made to Austria in 1636. The African peoples along the coast still yearned for freedom, and in 1650, a rebellion against the Bihari led to the declaration of a new Chiefdom of Swahili by Muhammad Kilwa.

East Africa in 1650:

The tiny new state was an immediate target for invasion. As if defending itself from a Bihari attempt to recapture the territory was not enough, Malacca declared war the following year. Kamborapasu Kagona of Mutapa allied with his fellow Animists, hoping to prevent the Muslims from spreading their faith in the region again. But though Kilwa was able to buy off the Malaccans, a more determined invasion force came from even farther away. The Manchurians had also declared war, and brought in their Ming and Vijayanagari allies. As it happened, it was Ming that was able to land the superior force and in 1653, they annexed Swahili.

Having destroyed the Swahili, both Malacca and Ming pressed south into Mutapa. By 1656, Kamborapasu was forced to cede the coastal province of Sofala to Malacca, nearly cutting his people off from the sea and its valuable trade routes. By 1657, a 18,000 strong force from Vijayanagar was pressing into the Mutapan interior. Desperate to avoid extinction, in 1659 he delivered more than 800 gold bars to the Manchurian envoy to end the invasion.

The more advanced nations from both east and west continued to bully the unfortunate Mutapans through the next few decades. An even larger monetary settlement was demanded by the Austrians following the war of 1660-1663. The Malaccans attacked again in 1662 and seized the province of Uteve three years later. Kamborapasu’s successor, Nechagadzike was no more successful. The Manchu came back with demands for still more gold in 1669 and he was powerless to stop him.

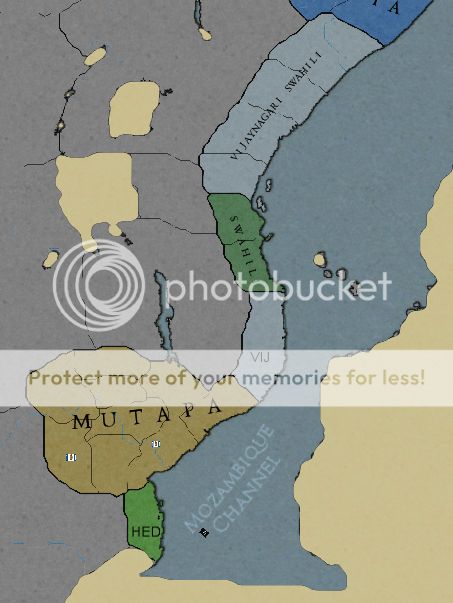

The Austrians were not the only European powers taking an interest in southern Africa. The English had begun building settlements along the southern tip of Africa, while the Atlantic Coast had attracted settlers from Berry, Etruria, Sweden and Castille. The entire coast from the Danish Congo to the Cape was in European hands by 1669. The Castillians used their new colony in Damaraland as a staging ground for an assault on Mutapa. By 1672, they had captured the important ivory producing port of Quelimane, severing Mutapa’s last link to the sea. However, the Castillians were unable to quell the spirit of the inhabitants, and by 1679, rebel forces had recaptured the province and made it part of Mutapa once again.

In 1677, Malacca attacked again, both because the death of Nechagadzike had left the Mutapans in political disarray, and because of their frustration with Mutapan support for Animist zealots in its African provinces. For a time, the rebels succeeded in controlling all of Malaccan Africa, but by 1681, Malaccan forces had once more defeated the Africans. While Malacca struggled with the invasions, the European influence in the region spread with Danish colonies being founded in Madagascar, while Leinster settled the islands to the east. By the 1680’s, it seemed doubtful that any native African states would survive in East Africa.

Southern Africa in 1684:

East Africa was still beset by foreign invaders in the mid-17th century. They had been assailed not only by the Indian powers of Bihar and Vijayanagar, but by Europeans and even the Chinese. Though these newer invaders had failed to grasp a permanent foothold in the region, they had on occasion forced Mutapa to surrender large sums of gold from their rich mines in the interior, most memorably the large payments made to Austria in 1636. The African peoples along the coast still yearned for freedom, and in 1650, a rebellion against the Bihari led to the declaration of a new Chiefdom of Swahili by Muhammad Kilwa.

East Africa in 1650:

The tiny new state was an immediate target for invasion. As if defending itself from a Bihari attempt to recapture the territory was not enough, Malacca declared war the following year. Kamborapasu Kagona of Mutapa allied with his fellow Animists, hoping to prevent the Muslims from spreading their faith in the region again. But though Kilwa was able to buy off the Malaccans, a more determined invasion force came from even farther away. The Manchurians had also declared war, and brought in their Ming and Vijayanagari allies. As it happened, it was Ming that was able to land the superior force and in 1653, they annexed Swahili.

Having destroyed the Swahili, both Malacca and Ming pressed south into Mutapa. By 1656, Kamborapasu was forced to cede the coastal province of Sofala to Malacca, nearly cutting his people off from the sea and its valuable trade routes. By 1657, a 18,000 strong force from Vijayanagar was pressing into the Mutapan interior. Desperate to avoid extinction, in 1659 he delivered more than 800 gold bars to the Manchurian envoy to end the invasion.

The more advanced nations from both east and west continued to bully the unfortunate Mutapans through the next few decades. An even larger monetary settlement was demanded by the Austrians following the war of 1660-1663. The Malaccans attacked again in 1662 and seized the province of Uteve three years later. Kamborapasu’s successor, Nechagadzike was no more successful. The Manchu came back with demands for still more gold in 1669 and he was powerless to stop him.

The Austrians were not the only European powers taking an interest in southern Africa. The English had begun building settlements along the southern tip of Africa, while the Atlantic Coast had attracted settlers from Berry, Etruria, Sweden and Castille. The entire coast from the Danish Congo to the Cape was in European hands by 1669. The Castillians used their new colony in Damaraland as a staging ground for an assault on Mutapa. By 1672, they had captured the important ivory producing port of Quelimane, severing Mutapa’s last link to the sea. However, the Castillians were unable to quell the spirit of the inhabitants, and by 1679, rebel forces had recaptured the province and made it part of Mutapa once again.

In 1677, Malacca attacked again, both because the death of Nechagadzike had left the Mutapans in political disarray, and because of their frustration with Mutapan support for Animist zealots in its African provinces. For a time, the rebels succeeded in controlling all of Malaccan Africa, but by 1681, Malaccan forces had once more defeated the Africans. While Malacca struggled with the invasions, the European influence in the region spread with Danish colonies being founded in Madagascar, while Leinster settled the islands to the east. By the 1680’s, it seemed doubtful that any native African states would survive in East Africa.

Southern Africa in 1684:

By the 1680’s, it seemed doubtful that any native African states would survive in East Africa.[/SIZE]

I'm actually pretty surprised they lasted this long. In my games, they usually get destroyed way before that.

They have a tendency to hang around in my games, if only b/c the AI is poor at controlling rebellions in far away lands. Still, until the coast is completely settled most nations will avoid taking more than the coastal provinces of the natives.

I don't know why, but for some reason Ming Africa seems way more absurd to me than Etrurian Africa...

@dodedo, I am planning to use HoD, because I think that the new "newspaper" features will be really helpful in constructing the AAR. I've found EU3 quite a bit more difficult to write for than CK2 because it's more abstract and Vicky 2 is more abstract still, so I'll need all the help I can get. Hopefully, it will be out by the time the EU3 section of the AAR is complete.

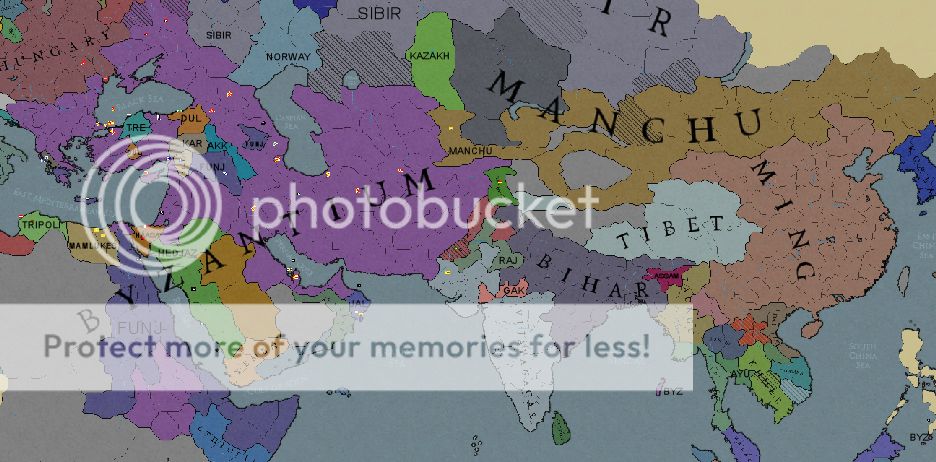

BYZANTINE CONSOLIDATION AND THE PUNITIVE WARS, 1648-1695

Where his predecessors had concentrated on conquering the East, Andreas Kantekouzenos decided that he would focus his reign on centralizing authority in the Empire. The empire had many vassal states that had been ruled by their own families for centuries. These vassals were willing to assist in times of war but a single unified Imperial army would be more efficient, especially since due to the vagaries of inheritances over the centuries, many vassals were fragmentary. Soon after taking the throne, Andreas dissolved one of the largest of these, the Kingdom of Greece. He divided the former realm of Georgios Komnenos between several Exarchs, and while the Komnenos family would still own extensive lands, the exarchates would not be hereditary.

In the 1650’s, he became irritated by the ongoing Muslim resistance to conversion in the territories of southern Arabia. He was repeatedly forced to crush revolutionary Jalayirids and make them swear allegiance again, and lost control of Bahrein and Qatar to Sicily due to rebel defections. Despite these setbacks, his larger plan continued as he intended, with the annexation of the Kingdom of Kazan, tightening Byzantium’s hold on the steppes north of the Black Sea.

In 1665, the Sicilians launched an ill-advised war to recover the province of Al Hasa, calling in a gaggle of minor non-Christian states as allies: the Jalayirids, Omani and Kazakh (which had recently rebelled against Sibir). Despite their best efforts and the difficulties of fighting in the harsh desert lands, it was over by 1670. The Kazakhs and Jalayirids were forced to become vassals once more, while the others made monetary payments in return for peace. The Empire reached the apex of its power. Emulating its neighbors to the west, it had even begun a tentative colonization program, placing settlements on the Andaman Islands and Sulu in the East.

However, the Empire’s neighbors and even its vassals were starting to look askance at its growing power. The Emperor’s reputation hit an all-time low after he dissolved the Duchy of Haasa in 1678. Doux Dudjayn of Lezhnevo did not take kindly to the disinheriting of his family in favor of the Emperor’s handpicked men. He roamed the world complaining about how his wife’s kinsman had disregarded the centuries of loyal service his family had given the Empire. The complaints and the resulting unrest in the Empire drew the attention of its neighbors.

Byzantium in 1678:

This sparked the beginning of the so-called Punitive Wars. It started with relatively minor skirmishes that only caused difficulties because they occurred at the far reaches of the Empire. In the summer of 1678, against the backdrop of another rebellion of Kazakhs, Kashmir declared war and managed to persuade its more powerful ally, Bihar to join it. Meanwhile in the north several members of the Holy Roman Empire—Zaparozhe, Nizhny Novgorod, Moldavia—declared war on him.

In two years, Andreas was able pacify the Kazakhs and exact tribute from Zaparozhe and its allies but by that time, he was assailed from the south by the Ethiopians, who dragged in Yemen, Athens and Syria. Though none of these states posed much of a threat by itself, it made for an awkward war with many small fronts. In 1681, seeing that the Empire had still not punished the Kashmiris, the Punjabi’s also declared war, and brought in Gakwar. The little state of Gakwar took advantage of the Byzantine blockades of Ethiopia and Yemen to take control of the colonies in the Andaman Islands and Sulu.

He was able to campaign successfully on several fronts that year, crushing the newly formed Oirat Horde and forcing annual tribute, then turning south and defeating the Syrians and Yemeni. He chose to only take money in compensation not land, out of fear of further antagonizing his neighbors. It did little good, however, as Manchu attacked the following year, and persuaded Ming and Tibet to join in the assault.

Andreas died in 1683, throwing the Empire into confusion. Because of the death of his son some years earlier, the heir apparent was only eight years old. A regency council hastily formed, but the signs of weakness encouraged still more attacks. Vijayanagar joining its allies in Manchu on the eastern front was bad enough, and inspired the regents to make quick treaties with Ethiopia, Punjab, and Athens without demands despite their advantage in those wars. But it was the news in August that Hungary had joined the ranks of the Empire’s enemies, and brought in Austria and Navarra as allies that really alarmed the council.

The Austrians and Hungarians advanced through the Balkans, shocking the populace, especially the Austrians whose cannons and muskets were vastly more advanced than the Byzantine ones. While there had sometimes been border incursions, the heart of the Empire had not been invaded by a foreign army in more than four centuries. The regency struggled to impose its authority, leading to widespread peasant rebellions in Asia Minor and in the vassal state of Funj. Somehow they managed to extricate themselves diplomatically from the wars with Hungary and Manchu by 1685 but the Sicilians attacked again in the south later that year and were followed by Zaparozhe and its allies once again. 1688 saw another attack from Punjab and Kashmir. Though the Empire was able to deal with each of these threats in turn, it seemed that new wars would start each time they signed a treaty, and their manpower was rapidly dwindling.

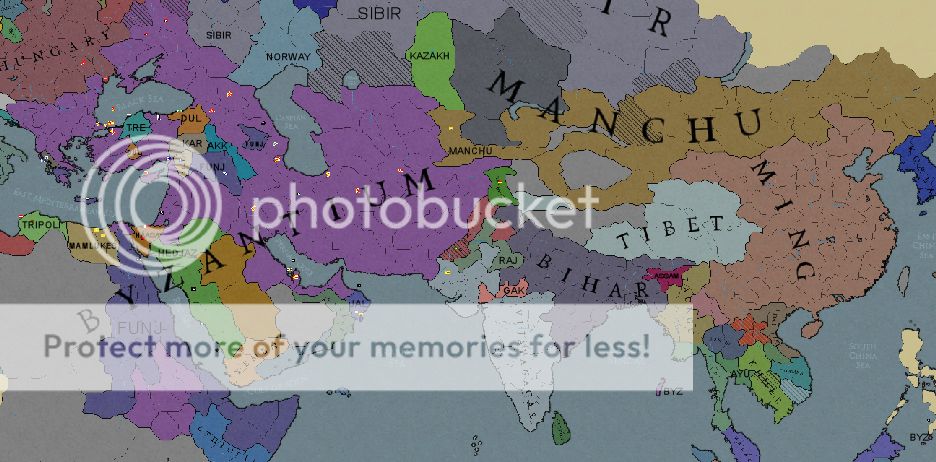

Manuel II finally came of age in 1689 and faced a dire threat almost immediately when Sibir and its ally Norway attacked. These dangerous new enemies were followed by renewed aggression in the west from Hungary, Austria and Navarra the following Spring. In the summer, Manchu, Ming and Vijayanagar broke the peace once more. With the Austrians advancing on Constantinople itself, Manuel was desperate to save himself. He ceded the Adriatic provinces of Usora and Zeta to Austria in the fall of 1690. Through brilliant diplomacy he made peace with several nations including Vijayanagar without concessions in 1691, and agreed to release Karaman from its vassal status in return for peace with Sibir.

Late that year, however, Manuel died mysteriously and left no legal heir. Support in the Imperial court coalesced around Andreas Doukas, in part because his name recalled the great Emperors of the past. But he was a distant relative of those great men and his legitimacy was dubious. Even so, he was able to cut a deal with Hungary, renouncing an old claim on Belgorod and giving Najd its full independence in 1693. With the European powers off his back, he was able to advance his campaigns in the east and by the fall of 1695, the Empire was at last at peace. Though in most cases, peace was made without terms, he was able to force the Manchurians to release a state called Durrani.

Though the Empire survived the Punitive wars with only minimal territorial losses, the damage was far greater than appeared on the surface. The feeling of safety which Imperial citizens had enjoyed for centuries was severely shaken, the Kantakouzenos dynasty had ended and the new dynasty was unproven. Worst of all, the relative backwardness of the Empire’s military technology had been badly exposed by its wars with Sibir, Hungary, and especially Austria. It remained to be seen whether the young Emperor could restore its faded glory.

Byzantium in 1696:

Where his predecessors had concentrated on conquering the East, Andreas Kantekouzenos decided that he would focus his reign on centralizing authority in the Empire. The empire had many vassal states that had been ruled by their own families for centuries. These vassals were willing to assist in times of war but a single unified Imperial army would be more efficient, especially since due to the vagaries of inheritances over the centuries, many vassals were fragmentary. Soon after taking the throne, Andreas dissolved one of the largest of these, the Kingdom of Greece. He divided the former realm of Georgios Komnenos between several Exarchs, and while the Komnenos family would still own extensive lands, the exarchates would not be hereditary.

In the 1650’s, he became irritated by the ongoing Muslim resistance to conversion in the territories of southern Arabia. He was repeatedly forced to crush revolutionary Jalayirids and make them swear allegiance again, and lost control of Bahrein and Qatar to Sicily due to rebel defections. Despite these setbacks, his larger plan continued as he intended, with the annexation of the Kingdom of Kazan, tightening Byzantium’s hold on the steppes north of the Black Sea.

In 1665, the Sicilians launched an ill-advised war to recover the province of Al Hasa, calling in a gaggle of minor non-Christian states as allies: the Jalayirids, Omani and Kazakh (which had recently rebelled against Sibir). Despite their best efforts and the difficulties of fighting in the harsh desert lands, it was over by 1670. The Kazakhs and Jalayirids were forced to become vassals once more, while the others made monetary payments in return for peace. The Empire reached the apex of its power. Emulating its neighbors to the west, it had even begun a tentative colonization program, placing settlements on the Andaman Islands and Sulu in the East.

However, the Empire’s neighbors and even its vassals were starting to look askance at its growing power. The Emperor’s reputation hit an all-time low after he dissolved the Duchy of Haasa in 1678. Doux Dudjayn of Lezhnevo did not take kindly to the disinheriting of his family in favor of the Emperor’s handpicked men. He roamed the world complaining about how his wife’s kinsman had disregarded the centuries of loyal service his family had given the Empire. The complaints and the resulting unrest in the Empire drew the attention of its neighbors.

Byzantium in 1678:

This sparked the beginning of the so-called Punitive Wars. It started with relatively minor skirmishes that only caused difficulties because they occurred at the far reaches of the Empire. In the summer of 1678, against the backdrop of another rebellion of Kazakhs, Kashmir declared war and managed to persuade its more powerful ally, Bihar to join it. Meanwhile in the north several members of the Holy Roman Empire—Zaparozhe, Nizhny Novgorod, Moldavia—declared war on him.

In two years, Andreas was able pacify the Kazakhs and exact tribute from Zaparozhe and its allies but by that time, he was assailed from the south by the Ethiopians, who dragged in Yemen, Athens and Syria. Though none of these states posed much of a threat by itself, it made for an awkward war with many small fronts. In 1681, seeing that the Empire had still not punished the Kashmiris, the Punjabi’s also declared war, and brought in Gakwar. The little state of Gakwar took advantage of the Byzantine blockades of Ethiopia and Yemen to take control of the colonies in the Andaman Islands and Sulu.

He was able to campaign successfully on several fronts that year, crushing the newly formed Oirat Horde and forcing annual tribute, then turning south and defeating the Syrians and Yemeni. He chose to only take money in compensation not land, out of fear of further antagonizing his neighbors. It did little good, however, as Manchu attacked the following year, and persuaded Ming and Tibet to join in the assault.

Andreas died in 1683, throwing the Empire into confusion. Because of the death of his son some years earlier, the heir apparent was only eight years old. A regency council hastily formed, but the signs of weakness encouraged still more attacks. Vijayanagar joining its allies in Manchu on the eastern front was bad enough, and inspired the regents to make quick treaties with Ethiopia, Punjab, and Athens without demands despite their advantage in those wars. But it was the news in August that Hungary had joined the ranks of the Empire’s enemies, and brought in Austria and Navarra as allies that really alarmed the council.

The Austrians and Hungarians advanced through the Balkans, shocking the populace, especially the Austrians whose cannons and muskets were vastly more advanced than the Byzantine ones. While there had sometimes been border incursions, the heart of the Empire had not been invaded by a foreign army in more than four centuries. The regency struggled to impose its authority, leading to widespread peasant rebellions in Asia Minor and in the vassal state of Funj. Somehow they managed to extricate themselves diplomatically from the wars with Hungary and Manchu by 1685 but the Sicilians attacked again in the south later that year and were followed by Zaparozhe and its allies once again. 1688 saw another attack from Punjab and Kashmir. Though the Empire was able to deal with each of these threats in turn, it seemed that new wars would start each time they signed a treaty, and their manpower was rapidly dwindling.

Manuel II finally came of age in 1689 and faced a dire threat almost immediately when Sibir and its ally Norway attacked. These dangerous new enemies were followed by renewed aggression in the west from Hungary, Austria and Navarra the following Spring. In the summer, Manchu, Ming and Vijayanagar broke the peace once more. With the Austrians advancing on Constantinople itself, Manuel was desperate to save himself. He ceded the Adriatic provinces of Usora and Zeta to Austria in the fall of 1690. Through brilliant diplomacy he made peace with several nations including Vijayanagar without concessions in 1691, and agreed to release Karaman from its vassal status in return for peace with Sibir.

Late that year, however, Manuel died mysteriously and left no legal heir. Support in the Imperial court coalesced around Andreas Doukas, in part because his name recalled the great Emperors of the past. But he was a distant relative of those great men and his legitimacy was dubious. Even so, he was able to cut a deal with Hungary, renouncing an old claim on Belgorod and giving Najd its full independence in 1693. With the European powers off his back, he was able to advance his campaigns in the east and by the fall of 1695, the Empire was at last at peace. Though in most cases, peace was made without terms, he was able to force the Manchurians to release a state called Durrani.

Though the Empire survived the Punitive wars with only minimal territorial losses, the damage was far greater than appeared on the surface. The feeling of safety which Imperial citizens had enjoyed for centuries was severely shaken, the Kantakouzenos dynasty had ended and the new dynasty was unproven. Worst of all, the relative backwardness of the Empire’s military technology had been badly exposed by its wars with Sibir, Hungary, and especially Austria. It remained to be seen whether the young Emperor could restore its faded glory.

Byzantium in 1696:

The AI's dealing with controlling Byzantium a lot better than I thought it would. Although the return of the Doukid doesn't bode well...

Sometimes. To predict whether or not they will, the best way is to look at their innovative-narrowminded slider and their centralization. They'll probably westernize at some point, but I feel it's going to be some time, and the massive stability loss to the already unsteady empire will probably cause it to shake itself into pieces. I'm sure they would still be powerful, but they would lose their territories on the periphery, no doubt.