In the Shadow of the Ancients - An Assyrian AAR

- Thread starter Tommy4ever

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

A couple weeks on from the death of my Persian AAR from file loss and I am already back for more. I hope this one can provide the same entertainment as its predecessor. This time we are moving over to Mesopotamia to follow the story of the Assyrians. I didn’t actually begin the game playing in the middle east (but as a Shia ruler in Sicily in the 1066 start), but shifted over once things started to look more interesting out east than in the neighbourhood I was actually playing in. As such we will quick off in the unconventional surrounded of the early 1100s to begin our story when we get into the first update proper.

Last edited:

- 1

- 1

Introduction: The Origins of the Assyrian Nation

Introduction: The Origins of the Assyrian Nation

Prior to the ascent of the first medieval Assyrian state, the Aramean-speaking Syriac Christians of the Middle East had little sense of collective national identity. This population, having been the largest group across Mesopotamia and Syria at the time of the Arab Conquest, had dwindled by the end of the first millennium AD to the status of a scattered minority everywhere in their traditional homelands except for a small territory north of Baghdad, centred around the city of Samarra. They appeared to be a disjointed people drifting into the abyss of history. Yet, from these beginnings there would arise a new Assyrian nation. Its developed was genuinely remarkable, marking the novel forging of a coherent and powerful national identity among the Syriac Christians of the Near East alongside the revival of the unimaginably ancient idea of Assyria. The ethnogenesis of this nation rooted itself in three key pillars: ancestral and ethnic connection to the ancient civilisations of the Near East – most prominently Assyria itself, the Aramaic language and the Christian teachings of the Church of the East.

The Medieval architects of Assyrian nationhood consciously identified themselves as the indigenous population of the Near East who had been uprooted by interloping Arabs, Kurds, Greeks, Turks and Persians. They claimed to be the direct, undiluted, ancestors of the glories of the Cradle of Civilisation, to the Babylonians, Akkadians and above all the ancient Assyrians. This claim was granted credence by their use of the Aramean language, known as Syriac by the Greeks. Having originated in Syria, the Aramean tongue had developed into the dominant language of the Levant and Mesopotamia during the first millennium BC and remained so until the Arab conquest. It was the native language of Jesus Christ, was one of the main languages of the Talmud, was used in Babylon and Nineveh and at the courts of Persian Shahanshahs.

Just as important to the Assyrian idea as history and language was faith. Christianity arrived in Mesopotamia within the lifetime of the Apostles – soon establishing itself as one of the major religions of the area. While the Western Church solidified its structures and theology as the state religion of the late Roman Empire, the Christians beyond Rome’s eastern frontier in the Persian empire sought a different path. Receiving official sanction from the Sassanian Shah, the Church of the East was consecrated as an independent Church in 410, with its own Patriarch. The Church’s rise helped to further embed the linguistic foundations of the later Assyrian people, as literary Syriac – based on the Aramaic dialect spoken in the religious centre of Edessa – emerged as the liturgical language of the eastern Church.

The Persian Church had a number of theological differences with its Roman counterpart, chief among these was Nestorianism. Nestorius had been the Patriarch of Constantinople, one of the most influential positions in the Roman Church, and posited the idea that the human and divine nature of Jesus were distinct and separate. After Nestorius and his teachings were deemed heretical by the Councils of Ephesus and Chalcedon, many of his followers fled eastward into the Persian empire where they imprinted their ideas onto the emerging Church of the East.

From this time, the Church flourished – becoming the largest religion in its core Mesopotamian territories and achieving influence not only within the Sassanian empire but far beyond. There were sizeable Nestorian dioceses in Indian, where the St Thomas Christians of the Malabar Coast were in communion, and notable communities throughout the tribes of Central Asia and even in distant China.

The cataclysmic upheavals of the seventh century, with the rise of Islam and conquest of the entire Middle East by the Rashidun Caliphate set in motion the decline of the Aramean-speaking peoples and their Church. Many Syriac Christians had welcomed the Muslim takeover, that relieved them from the oppression of Zoroastrian Persians, shielded them from the interference of Roman clerics and granted them protection as People of the Book. Indeed, Aramean speaking Christian scholars played a vital role in the Islamic Golden Age with their translation of ancient texts, and their culture flourished in tandem with that of the Caliphate. Nonetheless, over the generations Islam and Arabic gradually replaced Christianity and Aramean across the Near East. As the centuries passed, the Syriac Christians retreated back ever further – increasingly concentrating in the plains of northern Mesopotamia, in the lands of ancient Assyria. It would be here, in the early twelfth century, that this age of retreat was ended and the Assyrian nation was born.

- 10

- 1

Glad to see you back in action, Tommy  Once again you've managed to find an initial scenario that I find rather fascinating. Definitely looking forward to see how the Assyrians struggle to find their place in the sun once more.

Once again you've managed to find an initial scenario that I find rather fascinating. Definitely looking forward to see how the Assyrians struggle to find their place in the sun once more.

- 2

Thank you very much for returning with a new AAR. 1000 Near East appears to resemble the 2000 Near East with minority religions/cultures getting the rawest deals.

- 1

- 1

Assyria will rise again!

I wonder if the Assyrian Church will displace its opposing churches, like Orthodoxy and Catholicism, but the Muslims must be dealt with first...

I wonder if the Assyrian Church will displace its opposing churches, like Orthodoxy and Catholicism, but the Muslims must be dealt with first...

- 1

I am following this eagerly! I only found the Persian AAR last week - imagine my disappointment to discover that it had ended prematurely! But I am excited for this project.

- 1

A People Are Born 1129-1138

A People Are Born 1129-1138

The Assyrian nation was forged during a period of tremendous flux in the Middle East caused by the dramatic waxing and waning of Turkish power. The Seljuk Turks had descended from their Steppe Homeland during the first half of the eleventh century to conquer a mighty empire stretching across Persia, Central Asia and Mesopotamia – making the Abbasid Caliph their vassal and establishing themselves as the greatest power in Sunni Islam. In the latter part of the century they attempted to push their power yet further – invading both the Shia Fatimid-ruled Levant and Byzantine controlled Anatolia. In both cases, they met with initially success – taking lands in Syria and Armenia – yet were ultimately forced to relinquish their gains before the end of the century. This stunting of the Turks’ expansionist ambitions robbed the Seljuks of their reputation for invincibility and promoted internal disquiet that would come to the fore under the strains of the century to come.

The Turkish empire was tipped from stagnation to crisis by the mass migration of another Turkic Steppe nation into their empire – the Jewish Khazars. Having once been the leading power on the western Eurasian Steppe, the Khazars had been forced from their traditional homelands by more aggressive Cuman tribes. In the late 1110s and the 1120s they made the journey around the eastern coastline of the Caspian Sea to invade the northern provinces of the Seljuk Empire. The Turks had little response to the arrival of the Jewish tribes in their tens of thousands, facing a string of military defeats that forced them to surrender the souther shore of the Caspian to a new Khazar Khaganate and allow for the migration of the entire Khazar nation from the north. The arrival of the Khazars gravely sapped the strength of the Turks, destabilising the entire Middle East.

The threat of foreign invasion was compounded upon by internal discord and religious schism. The movement of the messianic self-declared Islamic Mahdi, Hussein Zikrid – known as the Zikri – had risen rapidly across Iran, Mesopotamia and the Persian Gulf from last years of the eleventh century. Promising a reordering of society, a return to true religion and the imminent coming of the end of days, by the time of the Khazar invasion, the Zikri were increasingly challenging the dominance of the Sunni traditionalists – winning particularly widespread support in eastern Persia, southern Iraq and among the Kurds. The Zikri turned to revolutionary violence in the 1120s, embarking on major rebellions against their Sunni Turkish overlords that rocked the Seljuk state. At the same time, the Abbasids in Baghdad, fearing that the Seljuks were no longer capable of carrying the sword for the Caliph rose up in pursuit of their own independence.

Among the many warlords vying for a share of the spoils as the Seljuk Empire teetered on the brink of collapse was a Syriac Christian tribal leader hailing from the countryside near the city of Samarra. This was the man who would become known as Saint Ta’mhas the Great. Among his many epitaphs, Ta’mhas the Scholar, the Lion of Assyria, the Father of the Nation. The man who would do more than any other to forge the idea of an Assyrian people, and rise to a status of religious veneration within the Church of the East, his Qatwa bloodline taking on almost sacred significance among the adherents of the Nestorian Church.

Ta’mhas made his entrance into history in 1129 when he led a small band of Aramaic tribal warriors into the Christian-majority city of Samarra – taking advantage of the withdrawal of most its previous Turkish garrison. Over the next two years he would fight bitterly to secure his rule over his small territory – pushing east to take Kurdish Kirkuk and west to capture further Assyrian populated territory at Deir. Nonetheless, his position as Malik of Samarra remained contested with the Seljuks still desperately hanging on to their power while larger Kurdish and Arab Muslim armies swirled across the region. Ta’mhas took a major step towards security in 1131 when he joined with the Abbasids to fend off a Turkish siege of Baghdad, in doing so gaining the Caliph’s recognition of his claims. The first Assyrian Christian realm was born.

The Malik knew well that his position, surrounded by more powerful Muslim states, remained extremely tenuous. He therefore set out to strike against the last major outpost of Seljuk power in northern Mesopotamia at Mosul in 1132, the largest city in a region home to a large Christian population. Even in their wildest fantasies, few Assyrians would have predicted the scale of their success in this initiative as Ta’mhas and his ragtag army faced down a Seljuk force four times their number at the Battle of Nimrud and completely destroyed it – effectively ending serious Turkish influence north of Baghdad. As the Christians entered Mosul, their domination over the fertile Plains of Nineveh and all the lands from Samarra to the Anatolian mountains seemed certain.

However, as the Turkish power evaporated, the Kurdish majority of the region rose up to seize power for themselves in opposition to both their foreign masters and the Assyrians. With Ta’mhas’ men being routed from their attempts to move into Sinjar and Nisibin, the Kurds sought to track the Christian army in recently captured Mosul. There Ta’mhas waited for two long years in the face of an overwhelmingly large Kurdish host. All seemed lost after a group of Muslims inside the city opened the gates – allowing the Kurds to begin to pour inside. There, in what appeared a final stand Ta’mhas led out his men and not only halted the Kurds but sent them into a chaotic retreat that allowed him to sally forth and scatter them. Despite this great victory, the fighting was far from over. Still benefiting from much greater numbers, the Kurds continued to menace the Assyrian presence around Mosul for several more years before finally agreeing to a truce in 1136 that allowed Ta’mhas to retain control over the city but left the rest of northern Mesopotamia in their hands.

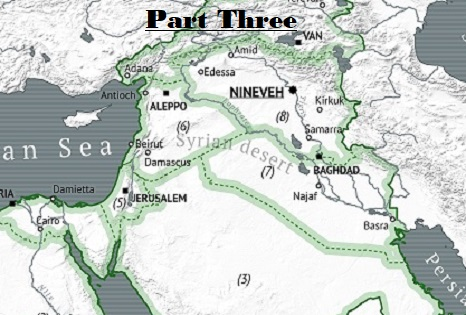

Shortly after the truce with the Kurds, Ta’mhas led his armies into a war against the isolated Turkish Beylik of Rahbah, who controlled a small Syriac-majority territory along the Euphrates. The victorious conclusion of this smaller conflict in 1138 marked the end of almost a decade of constant warfare for the nascent Assyrian state. Further to the east, the end of the 1130s also marked the conclusion of the Seljuk’s great crisis. After fending the Abbasids from Basra and holding the line against the Khazars along the new frontier in the Alborz Mountains, the Turks, admittedly diminished, had stopped the rot of their empire and clung onto their imperial power in Persia. Through these years of fighting, Malik Ta’mhas had established control over a rich Mesopotamian territory featuring a number of the area’s most important cities in Mosul, Samarra and Kirkuk. Furthermore, although within this territory Assyrian Christians formed a plurality of the population, only outnumbered by the combined numbers of Kurds and Arabs, Sunnis, Shia and Zikris. Now entering a period of peace, this new realm had the opportunity to take its first steps towards defining itself as a nation.

- 9

- 1

And we are off! So as I mentioned prior to the intro update, I started this game in 1066 as a Shia in Sicily (a state that didn't survive very long after my tag switch sadly). In the early 1100s thing start to get very interesting in the east - with the Khazars migrating into Daylam (the Persian Caspian) - giving us a flood of Jewish provinces to boot. As the Fatimids hold most of the Muslim holy sites, Sunni Islam is absolutely riven by heretics - the main one in the Seljuk empire being the Zikris who provide fuel for a large number of rebellions. Then of course the Abbasids break free. In game Samarra was actually a Nestorian religious revolt from the Abbasids (who were at the time fighting for their independence from the Turks and therefore distracted).

After independence, as a successful revolt we had a bunch of event troops and so invaded the province of Mosul - defeating the Turks as it says in the story. Then there was a huge Kurdish uprising (I have rebellions set to very powerful - so we were talking tens of thousands). Fending off those rebels proved much harder than fighting the Turks and I barely clung on to keep Mosul itself. But here we are, a little more secure than before and in control of a fairly wealthy stretch of real estate. We rule all 3 Assyrian-Nestorian provinces (Deir, Samarra and Rahbah) as well as two Kurdish Sunni ones (Mosul and Kirkuk).

Glad to see so many of you come aboard from the first! I'm glad a number of you seem to be particularly interested in the new Assyrian setting we have chosen. My interest in this particular area was actually piqued after seeing the Assyrians playing an (admittedly minor) role in my Persian AAR and starting to do a little reading on them. When I saw them lead a successful revolt in this game (while the also very interesting Khazar-Jewish invasion of Persia) I knew this was where the real story in this game was.

After independence, as a successful revolt we had a bunch of event troops and so invaded the province of Mosul - defeating the Turks as it says in the story. Then there was a huge Kurdish uprising (I have rebellions set to very powerful - so we were talking tens of thousands). Fending off those rebels proved much harder than fighting the Turks and I barely clung on to keep Mosul itself. But here we are, a little more secure than before and in control of a fairly wealthy stretch of real estate. We rule all 3 Assyrian-Nestorian provinces (Deir, Samarra and Rahbah) as well as two Kurdish Sunni ones (Mosul and Kirkuk).

Ohhh, I love Assyrian history, wonderful.

Glad to see you back in action, TommyOnce again you've managed to find an initial scenario that I find rather fascinating. Definitely looking forward to see how the Assyrians struggle to find their place in the sun once more.

Thank you very much for returning with a new AAR. 1000 Near East appears to resemble the 2000 Near East with minority religions/cultures getting the rawest deals.

Ok, I’m in my friend.

Assyria will rise again!

I wonder if the Assyrian Church will displace its opposing churches, like Orthodoxy and Catholicism, but the Muslims must be dealt with first...

Eager to read more!

I am following this eagerly! I only found the Persian AAR last week - imagine my disappointment to discover that it had ended prematurely! But I am excited for this project.

Glad to see so many of you come aboard from the first! I'm glad a number of you seem to be particularly interested in the new Assyrian setting we have chosen. My interest in this particular area was actually piqued after seeing the Assyrians playing an (admittedly minor) role in my Persian AAR and starting to do a little reading on them. When I saw them lead a successful revolt in this game (while the also very interesting Khazar-Jewish invasion of Persia) I knew this was where the real story in this game was.

- 6

- 2

It begins! The foundations of a free Assyria are small, but they do exist. Everyone starts small, after all...

- 1

A very harrowing start, but Assyria appears to have bought itself some breathing room for the time being.

- 1

Kingdom Come 1138-1163

Kingdom Come 1138-1163

Having been formed through a decade of fighting in the midst of the collapse of Seljuk power west and north of Persia, the 1140s provided Ta’mhas Qatwa’s nascent state with a period of peace and nation building. The Malik moved his capital from his native tribal territory around Samarra to the larger city of Mosul in the north. In a move etched with the symbolic rejection of the legacy of the Islamisation and Arabisation of the Middle East and anchoring of his own Syriac people in the traditions of the ancient peoples of Mesopotamia, Ta’mhas renamed the city Nineveh, adopting the title the name of ancient Assyrian metropolis whose ruins were not far from its successor.

During this time Mosul, Samarra and Kirkuk became magnets for two key groups of refugees – Syriac Christians and Jews. The instability of the first half of the twelfth century in the Middle East, the shock of the Khazar invasion, the rise of a Christian realm in Mesopotamia and, later in the century, the beginning of the Crusader era in earnest, turned Islamic opinion against religious minorities. For Christians, particularly Syriacs but also Armenians, the attraction of Ta’mhas’ statelet were obvious and they were welcomed keenly to settle. Asylum for Jews, who suffered ever harsher repression than their Christian counterparts as Turkic, Arab and Kurdish leaders accused them of collaborating with the Khazars, was a less obvious outcome of the emergence of a new Assyrian regime on the Tigris, but they were nonetheless welcomed in large numbers – swelling their numbers in the major cities and setting a historic precedent.

Together, these groups of refugees would help to stimulate a cultural and commercial flourishing, while Ta’mhas maintained a cosmopolitan court in Nineveh featuring Christian Assyrians and Armenians, Jews, and Muslim Arabs and Kurds. The emerging Mosul intelligentsia, following the interests of their patron, paid close attention to the question of Assyrian nationality, with Ta’mhas sponsoring the composition of an epic poem in the Aramean language that told the story of ancient Assyria and traced an unbroken historic lineage to his own state – the Melekh Katwa.

For all the cosmopolitanism in the cities, the Samarran state was tightly aligned with the Church of the East. Breaking a generations’ old taboo that had long forbidden any attempt to concert Muslims was from their faith, Syriac clerics embarked on proselyting campaigns among the realm’s large Islamic populations. As might have been expected, these efforts outraged communities and regional actors alike – leading to at an at times violent backlash, including the murder of Bishop Aggai of Deir near Kirkuk by a group of Kurdish tribesmen.

Undoubtedly the upturning of social hierarchies that had seen Muslims robbed of their historically privileged position was a source of torment and anger. It not only fuelled outbursts of popular violence, but also sinister scheming at court in Nineveh. There, Ta’mhas was the victim of an assassination attempt in 1147 as a palace slave brandished a knife and set upon the sovereign while he held court. The assailant was unable to badly injure his ruler, and was sent to the city’s dungeons for interrogation. To the horror of the Malik, the would-be killer was sprung from his captivity that very night by a Muslim cabal who subsequently fled to the Kurdish city of Irbil across the frontier. After the Zikri Kurdish Gholamid Emir refused his demands to return the conspirators to him, Ta’mhas readied his armies for war.

The Gholamids were an imposing foe with a larger and more religiously and ethnically unified realm than their Assyrian counterparts, while their territories surrounded Nineveh on three sides. Malik Ta’mhas therefore adopted a highly aggressive strategy. In his opening gambit, he marched east quickly from Nineveh, taking Irbil’s defenders by surprise, storming the city and brutally sacking it to neutralise it as a potential threat. He then swung westward to meet the largest part of the Kurdish army by the foot of Mount Sinjar where, in a tightly fought encounter, the Christians won the day. Although Samarra had gained a clear advantage, this was far from the end of the conflict as the Gholamid Emir rallied his pious tribesmen for holy war and sent a plea to his fellow Zikri Muslims in the Zagros mountains to send aid. These new sources of manpower could not wholly turn the tide against the Assyrians, but they nonetheless forced Ta’mhas to row back from ambitions to annex the entire Emirate. After four years of fighting, the two sides reached a peace in 1151 that saw Ta’mhas gain control of Sinjar, Irbil and Nisibis – a place of great spiritual importance to Nestorians as site of what was once one of the greatest centres of Syriac theology and scholarship.

The Malik’s triumph in his war against the Kurds greatly enhanced the stature of his realm across the region – leaving Ta’mhas in control of all northern Mesopotamia. Following this victory, he beseeched the Patriarch of the East, Hnanisho, the spiritual leader of the Church of the East, to establish a permanent residency at Nineveh. The Church’s Patriarchate had been based in Baghdad for centuries from the Arab conquest, but during the instability of the 1120s and 1130s had relocated to the Persian city of Isfahan. Promised lands, the resources to construct a new residency, security, proximity to the largest part of his flock, and a place at the seat of power of the world’s only Nestorian Christian state, Hnanisho accepted this offer and arrived in Nineveh in 1155. Not long after his arrival, Hnanisho would proclaim Ta’mhas as the King of Assyria.

Born in the last years of the eleventh century, the great Assyrian King continued to lead military campaigns from the front well into his sixties. In the years following his war against the Kurds, the broken Gholamid Emirated splintered into a series of petty tribal states that Assyria routinely waged war against throughout the late 1150s – absorbing them into their growing realm one by one. Then, in 1160, a dispute broke out with the Armenians. A fellow non-Chalcedonian Christian nation, the Armenians might have appeared to be natural allies of Assyria. Nonetheless, the two Kingdoms came to blows over Edessa – strategic, prosperous and ethnically Armenian, but for the Assyrians it was of profound spiritual significance. Edessa had been home to Saint Ephrem, the father of the Syriac Christian tradition and the founder of the theological schools of Edessa and Nisibis that had incubated the Church of the East. Guided by force of destiny, Ta’mhas went to war in 1160. Edessa itself was extremely well defended and, while the conflict dragged on for three years and featured a number of battles across the frontier, the war was dominated by the long running Assyrian siege of the city. The attacking army was ravaged by raids, disease and occasional hunger, yet never relented in their attacks. Finally, in 1163 the walls were breached and the elderly King entered the sacred city in jubilation. Having achieved yet another great victory on the field of battle, Ta’mhas, now sixty five years old, was already gravely ill and barely had the strength to mount his horse. He would never set eyes upon the banks of the Tigris again, remaining in Edessa for several more months in a steadily worsening condition before passing away, bequeathing an incredible legacy to his two sons Niv and Nahir.

- 9

- 1

We have completed our rise from religious rebellion to Kingdom in a single reign!

For information, I didn't manually rename Mosul to Nineveh myself - but they are culturally linked name changes, which is a nice touch for such a small and little played culture. There are one or two other Assyrian linked name changed the game produces, I'm not sure if they share them with any other cultures. I did especially like having my capital in Nineveh!

From our humble origins, Ta'mhas has left behind a genuine regional power - albeit a culturally and religiously isolated one that is still dwarfed by the genuine big boys like the Byzantines and Seljuks (now somewhat recovered from their earlier crisis).

With that little bit of breathing room our great founder has turned Assyrian into a real Kingdom. Only time will tell if we can hang on to what we have gained, not only from external foes but domestic ones too. Afterall, the more we expand beyond the very small Assyrian cultured heartland, the more unhappy populations we will be absorbing.

For information, I didn't manually rename Mosul to Nineveh myself - but they are culturally linked name changes, which is a nice touch for such a small and little played culture. There are one or two other Assyrian linked name changed the game produces, I'm not sure if they share them with any other cultures. I did especially like having my capital in Nineveh!

It begins! The foundations of a free Assyria are small, but they do exist. Everyone starts small, after all...

From our humble origins, Ta'mhas has left behind a genuine regional power - albeit a culturally and religiously isolated one that is still dwarfed by the genuine big boys like the Byzantines and Seljuks (now somewhat recovered from their earlier crisis).

A very harrowing start, but Assyria appears to have bought itself some breathing room for the time being.

With that little bit of breathing room our great founder has turned Assyrian into a real Kingdom. Only time will tell if we can hang on to what we have gained, not only from external foes but domestic ones too. Afterall, the more we expand beyond the very small Assyrian cultured heartland, the more unhappy populations we will be absorbing.

- 5

- 1

The founder dies. What will the sons bring to Assyria? Thank you for giving me this little gem.

- 1

Ta'mhas will go down in history as the founder of a new Assyria, we hope that his children can continue that lineage.

- 1

- 1

Assyria is now an official kingdom, but the Muslims are probably still a threat. Let's hope that they're still preoccupied with fighting each other?

It's interesting that Jews are accepted, given some historical Christian attitudes towards them (although that was mostly European). I wonder if that could lead to profits in the future?

It's interesting that Jews are accepted, given some historical Christian attitudes towards them (although that was mostly European). I wonder if that could lead to profits in the future?

- 2

Dangerous enemies still surround Assyria, but Ta’mhas has managed to found his kingdom on a solid footing. Hopefully the ongoing general chaos will give his heirs time and opportunities to shore up their position and reclaim more of Assyria's ancestral empire.

- 1

- 1