InTveresting Times: An AfTver Action Report

- Thread starter Fyregecko

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Thank you the idiot is gone. Tver will live once again.

... or simply find a new pyschopathic idiot to be ruled by?

These are the Rurikovichs we are reading about.

The revenge of the narwhal was a joy to behold. Our Scot-Poolish hero had had enough. Well he is rather old. A new chi-p off the old block would be a good thing. For a moment I did think we'd be seeing nasty things happen to Poland and Scotland for good measure.

Pity poor Dmitri was just a rebel pretending to be have the best interests of Tver at heart. Just how are you going to deal with all that infamy?

Pity poor Dmitri was just a rebel pretending to be have the best interests of Tver at heart. Just how are you going to deal with all that infamy?

... or simply find a new pyschopathic idiot to be ruled by?

These are the Rurikovichs we are reading about.

Rurichoviches are very often a bucnh of murderous psychopaths (every single one) but only a decisive minority are morons, the chance that the empire of Tver would get a less capable Tzar is like... i don't know it's to small to be countable. But probably like 0.1 %

That letter was a work of art. Truly, Dobczyński knows how to work a turn of phrase. Among other things.

Oh man. Invading Poland is one whale of a task!

He who comes bearing a narwhal, by the narwhal should perish. Granted, if this was a Narva-related pun it would be better. But would I pass the opportunity up even if it's a little lacking? Neva!

He who comes bearing a narwhal, by the narwhal should perish. Granted, if this was a Narva-related pun it would be better. But would I pass the opportunity up even if it's a little lacking? Neva!

Yay! I am finally finished reading all this. Great AAR, worth he read, and I am eager hearing more!

Just fully caught up on this AAR now, and love it so far! It must be all the really blatant innuendo and desperately bad puns ( which are the best kind).

Looking forward to the next update.

Looking forward to the next update.

One thing I learned after reading this AAR- I'm not alergic to puns, otherwise i'd be dead already.

Great piece of work- been lurking for a while and finally decided to post. Shame that Dobczyński had to go, though. I hope he'll come back soon.

Great piece of work- been lurking for a while and finally decided to post. Shame that Dobczyński had to go, though. I hope he'll come back soon.

I love it Nice. The Tablet art style is so much crisper. 10/10 from my point of view!!

Thanks mate. I'll be mixing elements of the old and the new one, but most characters will now be done in the new style

Oh god this is glorious! This is why everyone needs a narwhal - to get rid of inconvenient fat oafs! Konni was a real idiot, the first truly incompetent sot the game generated for you, so good riddance to him. Although it was interesting that he was one of the few people to actually recall the familiar method of power transfer in Tver, despite not having intentionally initiated it himself. Did the game give you a stab hit for his death?

Narwhals are awesome. And yes, I'd been really lucky with rulers overall, so I could hardly complain, but I was very glad to see the back of him. No in-game Stability hit, though I bet the country was Destabilised when he hit the bottom of the stairs...

That Narwhal is priceless.

For git hunting, you need to conquer somewhere like Najd.

Very true (I also recently learned that James VI once received a camel as a gift - not sure if that's a compliment or not). Sadly, Najd is nowhere near my zone of influence and I have bugger all navy...but there's still over 150 years to go...

Your artwork really pops out with that shading!

Too bad that the Rurikoviches are becoming morons, although they excel at creative assassinations. Let's see how Aleksandr soon fairs against the enemies of Tver.

Thanks

Awww, Dmitriy is just a pretender. I was hoping that he'd be the one to save Tver from the incompetencies of Konstantin's reign. I'll join the chorus of praise for the new art style too.

Afraid so. Though I like to check out pretenders incase they look competent. Also, being called Kholmsky and appearing in Kholm, I knew that I at least wanted to use him for something.

Will this mean a return of Dobczyński?!

The dynasty isn't finished, if that's what you mean. I won't spoil anything though

that was spectacular ... revenge of the Narwhal

Dobby's resignation letter was a corker too - sort of thing that should be sent to every HR 'director' on a regular basis just to remind them (ahem ... stop ranting).

Like the new graphics, seems your new gizmo (shows off deep technical knowledge) allows slightly softer more rounded lines?

As you probably deduced, I've felt like writing this kind of a letter at times as well...

And yes, drawing smooth lines is indeed far easier on the new tablet. The difference between drawing on a tablet and looking at the monitor, compared with the new one where I actually draw on what I'm looking at is huge. I'll still use the old one for things like backgrounds, but, as above, characters will be done with the Galaxy Note.

Thank you the idiot is gone. Tver will live once again.

Thank the game, not me

Aleksandr V has a fondness of monocles, he can't possibly be a bad guy

Amen

The revenge of the narwhal was a joy to behold. Our Scot-Poolish hero had had enough. Well he is rather old. A new chi-p off the old block would be a good thing. For a moment I did think we'd be seeing nasty things happen to Poland and Scotland for good measure.

Pity poor Dmitri was just a rebel pretending to be have the best interests of Tver at heart. Just how are you going to deal with all that infamy?

Sadly Scotland (or North Britain as it's been widely known since about 1500...) is well outside my reach due to my lack of a decent navy (thank you Aleksandr II...). And the Infamy is a pain in the arse, but my best Diplomat is working on it. Aleksandr only has Dip 3 so I'm considering, in game terms, whether Dmitriy Kholmsky might be a better choice as Czar...

You will create Russia?

Same answer as a few pages ago

Rurikoviches have had the worst luck with gravity.

Gravity can be a pain in the...whatever you fall on. I try to vary the deaths, but ones involving falling people / objects / livestock just have so much potential!

That letter was a work of art. Truly, Dobczyński knows how to work a turn of phrase. Among other things.

Many other things *wink wink*

Brilliant AAR. I'll definitely follow it.

Thanks pal

Oh man. Invading Poland is one whale of a task!

He who comes bearing a narwhal, by the narwhal should perish. Granted, if this was a Narva-related pun it would be better. But would I pass the opportunity up even if it's a little lacking? Neva!

Splendidly punned milord! And yes, many provinces have excellent potential. Sadly, many are outwith my current range.

Yay! I am finally finished reading all this. Great AAR, worth he read, and I am eager hearing more!

Cheers mate, thank you for following and commenting

Just fully caught up on this AAR now, and love it so far! It must be all the really blatant innuendo and desperately bad puns ( which are the best kind).

Looking forward to the next update.

Thank you sir/madam

One thing I learned after reading this AAR- I'm not alergic to puns, otherwise i'd be dead already.

Great piece of work- been lurking for a while and finally decided to post. Shame that Dobczyński had to go, though. I hope he'll come back soon.

I think that bad puns are especially dangerous to sufferers...

And thank you. No character lasts for ever, and this is Mirin Janusz's retirement, but it's not the end of the dynasty. Fear not, the cheap smut will return!

@ All: I apologise for typoes, I don't have Word or equivalent on this new computer so I don't have a WP programme with a spellchecker...

Episode LV: MoTvernisation

Imperial Palace, City of Tver

The death of the Czar and the outbreak of the Kholmsky Rebellion spread unrest through the Empire of Tver like a badger spreading tuberculosis amongst prize cattle - that is to say, the danger was greatly exaggerated and used by a lot of rich people as an excuse for shooting furry mammals. Czar Konstantin IV had been arguably the worst monarch in the history of Tver, and few tears were shed at his passing. Those that were shed were tears of hilarity.

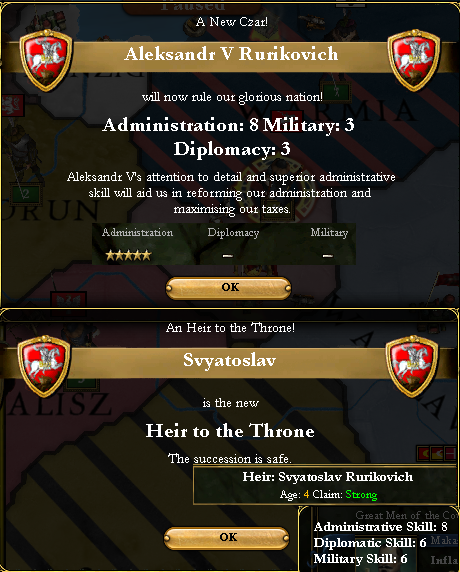

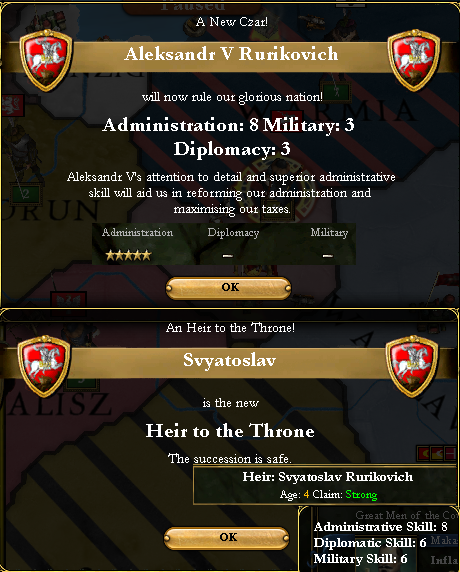

The Kholmsky Rebellion was a blow to the Empire's leadership. The popular, capable advisor had raised an army of followers and marched upon the capital, seeking to take the crown for himself. Prince Aleksandr, Kholmsky declared, was a half-Muslim bastard unworthy to sit upon the thrown of Tver (and, to be fair, the first half was technically true). The vast majority of Tver's nobility, though, stood behind the young Prince in spite of his tarnished heritage. Once Kholmsky was dead, it was decreed, Aleksandr would be crowned Czar of the Tverian Empire.

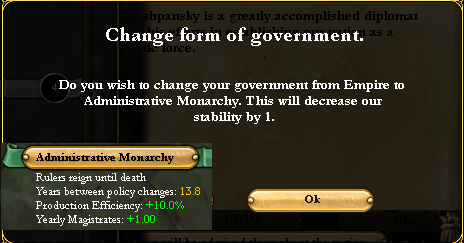

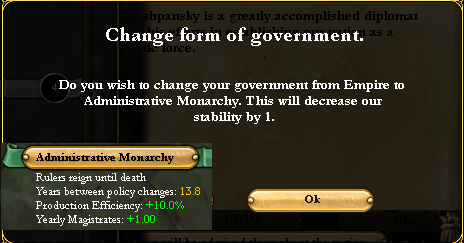

Aleksandr was a talented man - that is to say, he had a talent. He was a peerless administrator with piercing attention to detail. He liked nothing better than studying charts and statistics, calculating ways to optimise the running of the Empire. Even before his coronation, he embarked on an ambitious programme of administrative reforms to improve efficiency.

'The old systems were designed for the czarina Aleksandr, Mikulski. Fine for the time - hem - but quite outsated. We need changes, upgrades, modification and tinkering!'

'It sounds riveting, sir.' Captain Mikulski, temporarily promoted to Chief Advisor, did his best to appear enthusiastic. Thankfully for him, the Prince's talents did not extend to the judging of people's mood. Administration was his forte. People were his foible.

The changes, though, were undoubtedly effective, and the Empire soon saw increases in its income and improved efficiency in expansion, construction and colonisation projects.

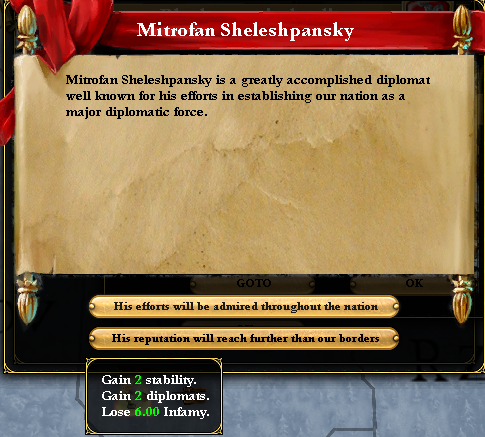

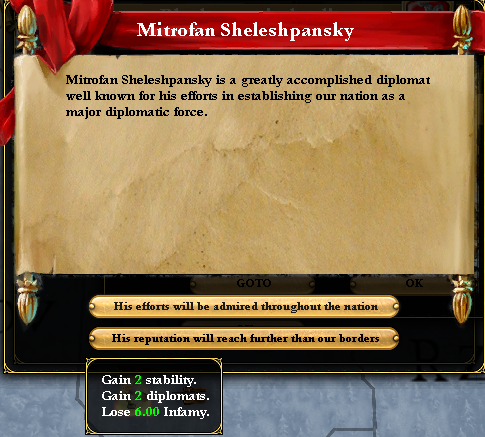

Another notable man of the period was the Chief Diplomat, Mirtofan Sheleshpansky (not, he constantly reminded the 'perfidious Poles' of the court, 'Szeleszpański'). His efforts were instrumental in improving the badly daamged reputation of the Empire in the courts of her neighbours. Tverian aggression, he argued, was purely a result of the warmongering tendancies of the previous Czar. With the Empire soon to be Under New Emperoragement, the days of reckless expansion and unnecessary warfare were over.

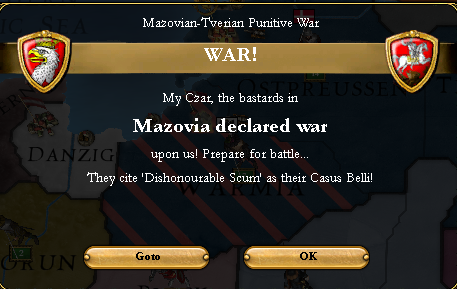

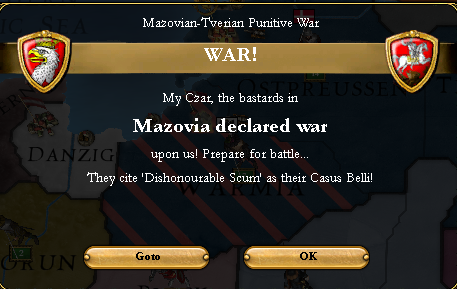

So impressed was the Duke of Mazovia, that he decided the time had come to take the best decision for his people. A small state surrounded by potential enemies, the Duke knew that the end of Mazovia's independence would come sooner rather than later. Here was a chance, though, to choose his countrymen's fate, and as a nation with a Bill of Rights guaranteeing the rights of minorities, seevral Polish provinces, and a long history of Polish senior advisors, the Empire of Tver seemed a far superior option to Mazovia's other, more ruthless neighbours.

The entry process, though, would be long and complicated, and the Duke decided to try an ambitious gambit: a direct application for membership and an open welcome for a Tverian delegation to oversee their entry into what one of his councillors called the 'Tverozone.

Prince Aleksandr was gratified by their enthusiasm, and was very happy to send a delegation to Mazovia. But he could not, sadly, agree to their request. Sucha rapid acquisition, given Tver's recently damaged reputation amongst the international community, would likely be seen badly amongst the courts of Europe - and might even be viewed as an annexation, whatever the Duke's protests to the contrary.

In addition, crucially, a speedy changeover would require the avoidance of Application Form AXL 2895 - a non-negotiable obstacle to membership. Application Form AXL 2895 (of which only three copies survive today) is reckoned by literary historians to be the fifth-largest book ever printed. Micro-print hardback copies are still recommended for home-defence use in parts of Russia, and an entire village was built from copies of the book in Rzhev Oblast, receiving in excess of 200, 000 tourists every year.

However, Aleksandr assured the Duke that their membership was Under Consideration, and recommended several steps to be taken in preparation for joining. The establishment of Orthodox Christianity would help to speed up their application, as would renunciation of Mazovia's claims on Warsaw (which, once inducted into the Empire, they would no longer need).

Matters administrative dealt with, the Czar Elect turned to the pressing matter of Kholmsky's rebellion.

'Mikulski! Find me General Sheleshpansky.'

'He's here, sir. Might want to put your monocle in.'

'Ah. Yes, that's better. General!'

'Sir!'

'You leave for Kholm immediately. I want this rebellion crushed like a recalcitrant bug under a hefty box of government papers.'

'Yes, sir.' Sheleshpansky exited. In truth, Sheleshpansky was not devoid of Kholmskyite sympathies. This would be his chance to assess the man's capabilities. After all, like Dobczyński before him, Sheleshpansky saw his duty as to the Empire of Tver, above that to the House of Rurikovich. If Kholmsky showed himself as capable on the battlefield as in the debating chamber...

The war with Denmark continued, with Danish troops advancing through Prussia into Tverian Poland. The assault on Warsaw, though, was ended by a rebel army originally founded to drive Tverian forces out of Warsaw but equally happen to unleash their fury on the Danish blockade of the city.

Mikulski was amused. 'Well, that's convenient.'

'Rather! Hem. Saves us a lot of effort if they can destroy each other.'

'Varsovians. Strange people. Not like they're known for uprisings or anyt hing...'

Exciting news reached the court of Tver. A Portuguese explorer had returned from wanderings in the far east, having discovered a new island. His journey had been long and hard, and half his ships crew had been mangaed on the way, but his enthusiasm, embodied by animeted gestures, was unbounded.

Sheleshpansky routed Kholmsky's disorganised forces with an ease which disappointed the general. The man was a capable negotiator, but an ineffective general. Sheleshpansky's loyalist troops drove him from the field. Kholmsky escaped, however, and before he could pursue the traitor Sheleshpansky received word of a fresh Danish offensive in the north-west. He rode to meet a fresh army to repulse the Scandinavian offensive.

The Battle of Olonets, though, wa sa disaster for the Tverian forces. Sheleshpansky's troops were unable to break their well-equipped, entrenched Danes, and forced to retreat, leaving the province in the enemy's hands.

The Danish attack was gathering momentum, and Tver's forces were pushed to try and contain their well-organised opponents. While Tverian units managed to move into Finland and take Kexholm, a two-pronged Danish assault on Tverian Poland and the Baltic coast gave them a distinct advantage. Able to concentrate their forces, the Danes, in spite of their far smaller size, posed a serious threat to the safety of the Empire's western provinces.

It was time for boldness - and nobody who had ever seen the inside of Sheleshpansky's wardrobe would ever doubt his boldness. Danish troops were assembled near the Baltic coast, presenting an opportunity to crush their assault force. Opportunity had reared her head - it was now, or Neva.

Tver's forces distracted, Polish rebels sought to break free from the Empire's grasp. United under the romantic Cracovian banner - in spite of having little support in Kraków itself - they drove Tverian troops out of and Sandomierz, and reclaimed the ancient Polish capital of Gniezno from Bohemia along with the rest of Sieradz province.

Prince Aleksandr redirected troops from the Danish front to face the rebels - but not quickly enough. The Cracovian Front declared their freedom under the banner of the new, independent Duchy of Kraków.

Their independence, though, was short-lived. Tverian troops, battle-hardened from the Danish Wars, rapidly overran both of the Duchy's provinces. Sandomierz was re-taken, and the opportunity to add Sieradz to the Empire was enthusiastically siezed. The Cracovian rebellion had paid a mighty dividend to the Empire of Tver.

Sheleshpansky returned to Tver to receive further orders. Prince Aleksandr was in an excellent mood.

'Ah, General! The conquering hero returns! Hem. My thanks for your valiant efforts against my enemies. And the Empire's.'

Sheleshpansky was taken aback.

'My thanks, your highness, but my work is barely started. The Danes have fought us to a bloody stalemate in the north-west. They still represent a very real threat to the Empire's safety.'

'Ah, we will deal with them in due course General! But the way you dealt with the traitor - exemplary!'

'The traitor, sir?'

'With Kholmsky, of course. Ruthlessly eliminated, exactly what I needed from you! Hem! Top show.'

'Sir...that wasn't me.'

'What? Of course it was you! Wasn't it him, Mikulski?'

'I...assumed that it was you in charge, General.'

'I was in Denmark, sir. I defeated Kholmsky several months ago as asked, but when I left before the hunt for his followers could begin.'

'Oh. Well. If you didn't deal with the traitor...'

'Well. I suppose it was inevitable. Going to kill me for your master, I suppose? My head displayed on a pike for all the Empire to see. Like every other rebel and traitor in our history. Death, I can take. But I can't stand predictability.'

'I say. That is original.'

'Well, regardless, he's dead. Hem. A pity, really. I always liked Kholmsky. Good thinker. I wonder what the last thing that went through his mind was...'

Imperial Palace, City of Tver

The death of the Czar and the outbreak of the Kholmsky Rebellion spread unrest through the Empire of Tver like a badger spreading tuberculosis amongst prize cattle - that is to say, the danger was greatly exaggerated and used by a lot of rich people as an excuse for shooting furry mammals. Czar Konstantin IV had been arguably the worst monarch in the history of Tver, and few tears were shed at his passing. Those that were shed were tears of hilarity.

The Kholmsky Rebellion was a blow to the Empire's leadership. The popular, capable advisor had raised an army of followers and marched upon the capital, seeking to take the crown for himself. Prince Aleksandr, Kholmsky declared, was a half-Muslim bastard unworthy to sit upon the thrown of Tver (and, to be fair, the first half was technically true). The vast majority of Tver's nobility, though, stood behind the young Prince in spite of his tarnished heritage. Once Kholmsky was dead, it was decreed, Aleksandr would be crowned Czar of the Tverian Empire.

Aleksandr was a talented man - that is to say, he had a talent. He was a peerless administrator with piercing attention to detail. He liked nothing better than studying charts and statistics, calculating ways to optimise the running of the Empire. Even before his coronation, he embarked on an ambitious programme of administrative reforms to improve efficiency.

'The old systems were designed for the czarina Aleksandr, Mikulski. Fine for the time - hem - but quite outsated. We need changes, upgrades, modification and tinkering!'

'It sounds riveting, sir.' Captain Mikulski, temporarily promoted to Chief Advisor, did his best to appear enthusiastic. Thankfully for him, the Prince's talents did not extend to the judging of people's mood. Administration was his forte. People were his foible.

The changes, though, were undoubtedly effective, and the Empire soon saw increases in its income and improved efficiency in expansion, construction and colonisation projects.

Another notable man of the period was the Chief Diplomat, Mirtofan Sheleshpansky (not, he constantly reminded the 'perfidious Poles' of the court, 'Szeleszpański'). His efforts were instrumental in improving the badly daamged reputation of the Empire in the courts of her neighbours. Tverian aggression, he argued, was purely a result of the warmongering tendancies of the previous Czar. With the Empire soon to be Under New Emperoragement, the days of reckless expansion and unnecessary warfare were over.

So impressed was the Duke of Mazovia, that he decided the time had come to take the best decision for his people. A small state surrounded by potential enemies, the Duke knew that the end of Mazovia's independence would come sooner rather than later. Here was a chance, though, to choose his countrymen's fate, and as a nation with a Bill of Rights guaranteeing the rights of minorities, seevral Polish provinces, and a long history of Polish senior advisors, the Empire of Tver seemed a far superior option to Mazovia's other, more ruthless neighbours.

The entry process, though, would be long and complicated, and the Duke decided to try an ambitious gambit: a direct application for membership and an open welcome for a Tverian delegation to oversee their entry into what one of his councillors called the 'Tverozone.

Prince Aleksandr was gratified by their enthusiasm, and was very happy to send a delegation to Mazovia. But he could not, sadly, agree to their request. Sucha rapid acquisition, given Tver's recently damaged reputation amongst the international community, would likely be seen badly amongst the courts of Europe - and might even be viewed as an annexation, whatever the Duke's protests to the contrary.

In addition, crucially, a speedy changeover would require the avoidance of Application Form AXL 2895 - a non-negotiable obstacle to membership. Application Form AXL 2895 (of which only three copies survive today) is reckoned by literary historians to be the fifth-largest book ever printed. Micro-print hardback copies are still recommended for home-defence use in parts of Russia, and an entire village was built from copies of the book in Rzhev Oblast, receiving in excess of 200, 000 tourists every year.

However, Aleksandr assured the Duke that their membership was Under Consideration, and recommended several steps to be taken in preparation for joining. The establishment of Orthodox Christianity would help to speed up their application, as would renunciation of Mazovia's claims on Warsaw (which, once inducted into the Empire, they would no longer need).

Matters administrative dealt with, the Czar Elect turned to the pressing matter of Kholmsky's rebellion.

'Mikulski! Find me General Sheleshpansky.'

'He's here, sir. Might want to put your monocle in.'

'Ah. Yes, that's better. General!'

'Sir!'

'You leave for Kholm immediately. I want this rebellion crushed like a recalcitrant bug under a hefty box of government papers.'

'Yes, sir.' Sheleshpansky exited. In truth, Sheleshpansky was not devoid of Kholmskyite sympathies. This would be his chance to assess the man's capabilities. After all, like Dobczyński before him, Sheleshpansky saw his duty as to the Empire of Tver, above that to the House of Rurikovich. If Kholmsky showed himself as capable on the battlefield as in the debating chamber...

The war with Denmark continued, with Danish troops advancing through Prussia into Tverian Poland. The assault on Warsaw, though, was ended by a rebel army originally founded to drive Tverian forces out of Warsaw but equally happen to unleash their fury on the Danish blockade of the city.

Mikulski was amused. 'Well, that's convenient.'

'Rather! Hem. Saves us a lot of effort if they can destroy each other.'

'Varsovians. Strange people. Not like they're known for uprisings or anyt hing...'

Exciting news reached the court of Tver. A Portuguese explorer had returned from wanderings in the far east, having discovered a new island. His journey had been long and hard, and half his ships crew had been mangaed on the way, but his enthusiasm, embodied by animeted gestures, was unbounded.

Sheleshpansky routed Kholmsky's disorganised forces with an ease which disappointed the general. The man was a capable negotiator, but an ineffective general. Sheleshpansky's loyalist troops drove him from the field. Kholmsky escaped, however, and before he could pursue the traitor Sheleshpansky received word of a fresh Danish offensive in the north-west. He rode to meet a fresh army to repulse the Scandinavian offensive.

The Battle of Olonets, though, wa sa disaster for the Tverian forces. Sheleshpansky's troops were unable to break their well-equipped, entrenched Danes, and forced to retreat, leaving the province in the enemy's hands.

The Danish attack was gathering momentum, and Tver's forces were pushed to try and contain their well-organised opponents. While Tverian units managed to move into Finland and take Kexholm, a two-pronged Danish assault on Tverian Poland and the Baltic coast gave them a distinct advantage. Able to concentrate their forces, the Danes, in spite of their far smaller size, posed a serious threat to the safety of the Empire's western provinces.

It was time for boldness - and nobody who had ever seen the inside of Sheleshpansky's wardrobe would ever doubt his boldness. Danish troops were assembled near the Baltic coast, presenting an opportunity to crush their assault force. Opportunity had reared her head - it was now, or Neva.

Tver's forces distracted, Polish rebels sought to break free from the Empire's grasp. United under the romantic Cracovian banner - in spite of having little support in Kraków itself - they drove Tverian troops out of and Sandomierz, and reclaimed the ancient Polish capital of Gniezno from Bohemia along with the rest of Sieradz province.

Prince Aleksandr redirected troops from the Danish front to face the rebels - but not quickly enough. The Cracovian Front declared their freedom under the banner of the new, independent Duchy of Kraków.

Their independence, though, was short-lived. Tverian troops, battle-hardened from the Danish Wars, rapidly overran both of the Duchy's provinces. Sandomierz was re-taken, and the opportunity to add Sieradz to the Empire was enthusiastically siezed. The Cracovian rebellion had paid a mighty dividend to the Empire of Tver.

Sheleshpansky returned to Tver to receive further orders. Prince Aleksandr was in an excellent mood.

'Ah, General! The conquering hero returns! Hem. My thanks for your valiant efforts against my enemies. And the Empire's.'

Sheleshpansky was taken aback.

'My thanks, your highness, but my work is barely started. The Danes have fought us to a bloody stalemate in the north-west. They still represent a very real threat to the Empire's safety.'

'Ah, we will deal with them in due course General! But the way you dealt with the traitor - exemplary!'

'The traitor, sir?'

'With Kholmsky, of course. Ruthlessly eliminated, exactly what I needed from you! Hem! Top show.'

'Sir...that wasn't me.'

'What? Of course it was you! Wasn't it him, Mikulski?'

'I...assumed that it was you in charge, General.'

'I was in Denmark, sir. I defeated Kholmsky several months ago as asked, but when I left before the hunt for his followers could begin.'

'Oh. Well. If you didn't deal with the traitor...'

'Well. I suppose it was inevitable. Going to kill me for your master, I suppose? My head displayed on a pike for all the Empire to see. Like every other rebel and traitor in our history. Death, I can take. But I can't stand predictability.'

'I say. That is original.'

'Well, regardless, he's dead. Hem. A pity, really. I always liked Kholmsky. Good thinker. I wonder what the last thing that went through his mind was...'

Last edited:

ah the wonders of modern bureaucracy ... but Svyatoslav looks one to cherish - he may have this father's taste for paper but much more rounded (though in that last picture Aleksandr does look a wee bitty portly)

@ loki100: Heh, well spotted, his stature in that portrait was a mistake - his slim build is one of his characteristics. Thanks for noting it, I've 'airbrushed' him to the way he should be

I wonder if a certain advisor took a pair of keepsakes when he left . . .

Also, that armor is very shiny, but the monocle makes the man. That and his complete lack of diplomatic and military ability.

Also, that armor is very shiny, but the monocle makes the man. That and his complete lack of diplomatic and military ability.

Alexandr looks especially grandiose thanks to the new shading (and the monocle!). Tablet MoTvernisation = Military MoTvernisation, hopefully? The game has made you wait far too long for that. That number of Danes should not be able to defeat a greater and more illustverious number of Tverians. Just take care to build up to your forcelimits before pressing the button, as the AI has a habit of insta-declaring war on anyone with red infamy and -3 stability.

Also, Svyatoslav is an interesting name. According to the game files, it's the most uncommon ruer name in Tver - but so is Konstantin. And Tver apparently has no women rulers. So either the file is just being silly or you changed it to make it more interesting =)

And the thing about the stab hit - it's just the game's way of noting whether your leader died 'naturally', or that your evil plan to kill him off succeeded - so in Konni's case it must have been the fat that got to him. It's one of the few times I'd be happy to receive a stabhit - though of course, there are no 'natural' deaths in Tver, only Natveral Selection!

Also, Svyatoslav is an interesting name. According to the game files, it's the most uncommon ruer name in Tver - but so is Konstantin. And Tver apparently has no women rulers. So either the file is just being silly or you changed it to make it more interesting =)

And the thing about the stab hit - it's just the game's way of noting whether your leader died 'naturally', or that your evil plan to kill him off succeeded - so in Konni's case it must have been the fat that got to him. It's one of the few times I'd be happy to receive a stabhit - though of course, there are no 'natural' deaths in Tver, only Natveral Selection!