Kurt_Steiner: Then there’s his Attorney General...

I have plans for Reagan, which may or may not include the White House. One of my several ideas is to run Reagan-Bush in 1976, which would naturally set Bush up in 1984. That idea has the advantage of already being developed; then again, I have several other ideas as well so who knows which way I’ll go. Once I get past 1968, the Presidents becomes really uncertain until 1984.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

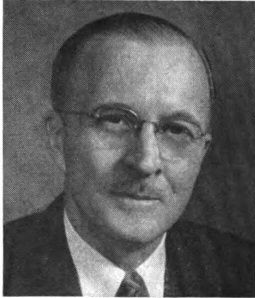

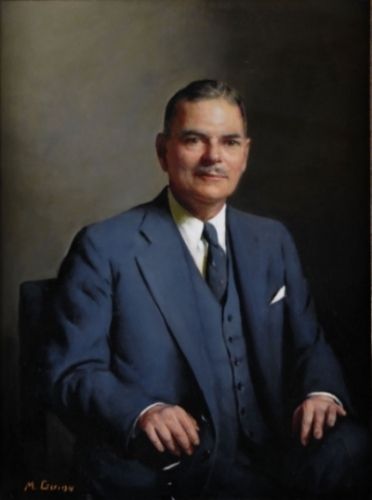

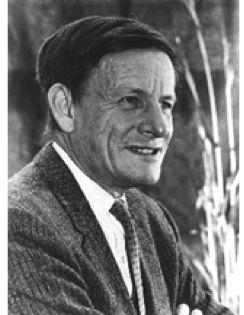

The Enforcer

“Court orders are precisely that: an order. They are to be obeyed like the word of God. If you believe a court order does not apply to you, you must be disabused of that notion in the strictest manner possible.”

-Attorney General Roger Ledyard

As the United States Attorney General in the early 1960s, Roger Ledyard took his job as the nation’s chief law enforcement officer very seriously. He had a black-and-white view of the world: the law was the law and it had to be enforced with the utmost zeal. Throughout his life, from his childhood in Groton, Connecticut to his submarine service in the Pacific during World War Two to his postwar legal career, Ledyard had a religious zealot-like attitude about following the rules and was willing to confront anyone who thought the rules didn’t apply to them. His unwavering commitment to the rule of law earned him the nickname “The Enforcer”, which Ledyard wore as a badge of honor as he climbed up the legal ladder to the top post at the United States Department of Justice. That he had an icy personality was something Ledyard freely acknowledged:

“I do not expect many people to like me. I do expect them to fear me, and it is my hope that this fear will compel them to do the right thing all the time.”

Serving as Attorney General at the height of the Civil Rights Movement, The Enforcer had no patience for the South. None. He coldly dismissed their arguments about states’ rights as

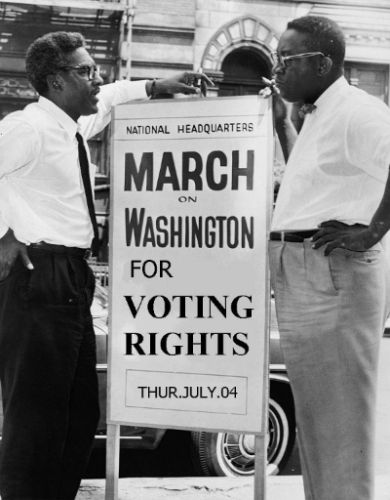

“meaningless words only a stupid person would utter” and prosecuted the South with gusto for their failure to fully adhere to civil rights laws and court orders. By January 1963, the Justice Department had sued seven Southern states for not following court orders in enforcing school integration and had sued seventy-five Southern counties over their excluding blacks from the polls (which was against the law). When the state of Mississippi tried to defy court-mandated school integration in the autumn of 1962, Ledyard decided to make an example out of the state by showing that resistance is futile.

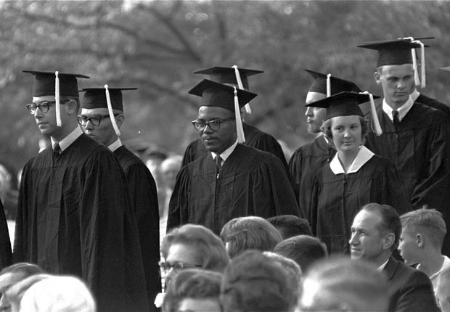

James Meredith could sense that the time was right. Born in Kosciusko, Mississippi in June 1933, the African-American escaped the strictly-segregated world of Mississippi by serving in the integrated United States Air Force during the 1950s. He left the Air Force in 1960, the year Vice President Henry M. Jackson was elected the country’s next President. When Jackson signaled in 1961 that he was going to embrace civil rights instead of ignoring it like his two predecessors had, Meredith became inspired to break the color line by applying for admission at the University of Mississippi in Oxford. The twenty-eight-year-old felt that it was time for the University of Mississippi to drop her policy of whites only, which was in defiance of the Supreme Court’s 1954 landmark decision ruling segregated public schools to be unconstitutional...and he was going to be the one who brought about that long-overdue change in policy. In his application for admission, Meredith wrote that he wanted to attend Ole Miss – her nickname – for the sake of his country, race, family, and himself.

“I am familiar with the probable difficulties involved in such a move as I am undertaking,” he wrote,

“And I am fully prepared to pursue it all the way to a degree from the University of Mississippi.”

Ole Miss denied him admission...twice. With support from Medgar Evers, the NAACP’s field secretary in Mississippi, Meredith filed suit with the United States District Court for the Southern District of Mississippi on May 31st, 1961, alleging that the university had rejected him solely on account of his race. He argued that his academic record was good enough to be accepted. The case went up to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, which ruled in Meredith’s favor. Mississippi then appealed to the Supreme Court, which on September 10th, 1962 upheld the ruling of the appeals court. Ole Miss was ordered by the High Bench to end its

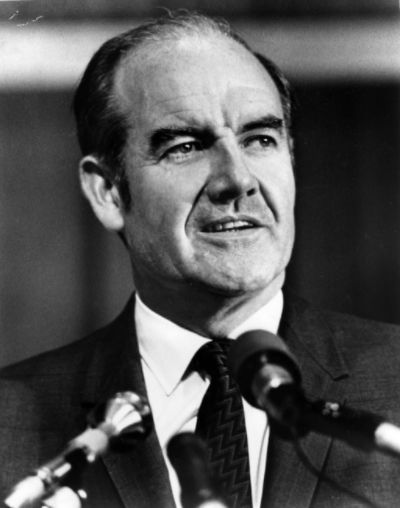

“calculated campaign of delay, harassment, and masterly inactivity” and admit him. In response to losing the court battle, Mississippi Governor Ross Barnett (a devoted segregationist) went on statewide television on September 13th to denounce

“this flagrant assault on our freedom to choose our way of life.”

Emotionally promising not to

“surrender to the evil and illegal forces of tyranny,” Barnett declared

“we must either submit to the unlawful dictates of the Federal Government or stand up like men and tell them ‘NEVER’.”

Barnett’s defiant pledge that

“no school will be integrated in Mississippi while I am your Governor” attracted Ledyard’s attention in no time. Calling the Governor’s speech

“the ramblings of a stupid man,” the Attorney General reacted the next day by suing the state of Mississippi for refusing to admit Meredith at Ole Miss. He called Barnett and asked him point blank,

“Are you out of your mind, Governor?”

Hearing this enraged Barnett:

“How dare you speak to me that way!”

“I am the Attorney General of the United States,” Ledyard retorted with no manner of politeness in his voice,

“I will speak to you as I damn well need to!”

He thought it was so stupid for the Governor to go on TV and

“act like you can ignore the law just because you don’t like it. I have news for you, Governor. YOU CAN’T!”

The two men angrily went back and forth for several minutes.

Barnett:

“Don’t you tell me what I can and can’t do!”

Ledyard:

“As the Attorney General, it’s my job to tell you what you can and can’t do!”

Ledyard had no sympathy for the South, which he made abundantly clear to Barnett. Returning the volley, Barnett called Ledyard

“a snow-digging Yankee Republican” who was too ignorant to understand that segregation was perfectly moral because the Bible said so.

“The Good Lord was the original segregationist,” he proclaimed,

“He put the black man in Africa...”

As he started to preach, Barnett suddenly heard the phone line go dead. After about ten or fifteen minutes of arguing with the Governor, the Attorney General finally got fed up and hung up on him midsentence.

“That man really is out of his mind,” he angrily told his deputy who watched the shouting match unfold with his eyes wide open. The fact that Barnett said with all seriousness that Mississippi had the largest percentage of African-Americans in the country because

“they love our way of life here, and that way is segregation” made Ledyard want to reach through the phone and strangle him. As he saw it, Barnett had no legitimate reason to argue with him whatsoever. The law was the law. The courts had ordered Ole Miss to register Meredith. Ole Miss had to register Meredith and let him enter the university because that is where he wanted to go. End of story. This

“pointless” resistance greatly angered Ledyard since it ran against everything he believed in. Concluding that he wasn’t going to get anywhere with Barnett over the phone, Ledyard decided that he would have to personally make the Governor obey the law. After discussing the matter with the President, the Attorney General flew to Mississippi. Meredith would get enrolled, one way or another.

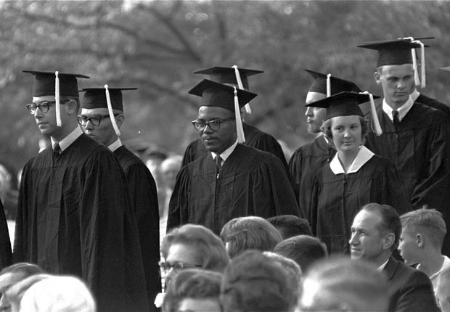

(Ole Miss)

(Ole Miss)

Barnett was fuming at the way he had been spoken to, so you can imagine his reaction when he learned that Ledyard had come to Jackson, Mississippi (the state capital) to see him personally. Not only that, the Attorney General had brought along six U.S. Marshals.

“Governor, you chose on your own not to enforce the law,” Ledyard told him sternly in his own office,

“So I have no choice but to come here and enforce the law myself.”

An undeterred Barnett informed Ledyard that he wouldn’t submit to Federal authority, having publicly vowed to resist integrating the University of Mississippi.

“Like I told you,” The Enforcer snapped,

“You do not have the right to ignore court orders!”

He then uttered his now-famous

“court orders are precisely that” line, followed by his announcement that the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit had just held Barnett in contempt of court for defying their order to enroll Meredith. He was to be arrested and fined $10,000 a day for each day he refused to obey their order. To drive home his intention to arrest the Governor, Ledyard signaled to one of the U.S. Marshals to brandish handcuffs in the most menacingly way possible.

“While you’re sitting in jail, Governor,” Ledyard added with cold straightforwardness,

“Your state will not be receiving another penny.”

When the Governor demanded to know what he was talking about, the Attorney General revealed that the President had issued an executive order that was to go into effect the moment Barnett was arrested. This executive order would withhold all Federal funds from the state of Mississippi for her not demonstrating

“compliance with the Constitution and the laws of the United States.”

The Jackson Administration, playing political hardball with the South in a way no other Democratic Administration would have dared, knew taking this legal step would hurt Mississippi because the state received $668 million from Federal coffers. If the Governor continued his refusal to comply with the court order, the stroke of Jackson’s pen would completely cut that off. In addition, Mississippi would see all her NASA, defense, and other Federal contracts be held up. Ole Miss would see her accreditation suspended and even her football team would be negatively impacted by being stripped of her postseason eligibility to participate in bowl games. Having forced Barnett into a corner by laying out the steep cost of his opposition to Federal authority, The Enforcer gave him a final ultimatum:

- He could back down, allow Meredith to enroll at Ole Miss, and figure out a way to spin his about-face in the best possible light. Taking his route would also void Barnett’s arrest, fine, and the executive order.

- He could be arrested, face the fine of $10,000 a day, and have Mississippi suffer greatly.

Either way, Ledyard would see to it that Meredith got enrolled. It was just a question of whether the process would be painless or painful...and only Barnett could answer that question.

“I Love Mississippi,” Barnett said,

“I would never do anything that would hurt her...”

When asked if that meant he would finally give in, the Governor blurted out the rest of his sentence:

“But what am I supposed to tell my people?! I gave them my word that I would never agree to let that boy get into Ole Miss!”

“Tell them the truth,” Ledyard answered,

“Tell them that the United States is a nation of laws and not of men. Tell them that every American citizen must abide by the law even if they disagree with it.”

The Governor looked down at the floor, staring intently at the polished tiles. He could sense that he was running out of time. He only had two options and he had to decide quickly. After what felt like an eternity, Barnett lifted his head up and shot an inquisitive look at Ledyard.

“Can I tell them you pointed a gun at my head?”

Ledyard stared right back at him.

“You can tell your people that we fired at you and missed for all I care.”

Under pressure, Barnett reluctantly decided that he wasn’t going to try to be a hero in the end. A short discussion followed and a deal was struck: Barnett would agree to allow Meredith to register in exchange for being granted a free hand to come up with a face-saving story about why he was doing what he said he wasn’t going to do just days ago. The Attorney General didn’t really care how the Governor would spin this; all he cared about was living up to his nickname.

On Thursday, September 20th, under the protection of 500 U.S. Marshals, Ledyard escorted Meredith onto the Ole Miss campus in Oxford. Knowing that the media was covering the event for newspapers and the evening news, the Attorney General wanted every American to see that he was personally overseeing the enforcement of the law. In the admissions office, Ledyard stood by and watched as university registrar Robert B. Ellis handed Meredith registration paperwork for him to fill out. In the meantime, the segregationist Governor was painting himself as someone who tried with all his might to prevent this moment from happening but was defeated by superior Federal power. In his victimized account of the meeting in his office, Barnett claimed that a U.S. Marshal had actually held a handgun against his head and had the gun ready to fire. Ledyard, upholding his end of the deal, neither confirmed nor denied the accusation. Although he was just doing his job of enforcing the law, the Attorney General couldn’t completely resist feeling pleased as he watched Meredith fill out the paperwork. This was after all an unprecedented moment: the first African-American student to enroll at the University of Mississippi. After Meredith had been led to his dorm room, Ledyard called the President at the White House to inform him that

“the rule of law has prevailed in the United States of America.”

While that was true, it didn’t mean that whites opposed to Meredith’s enrollment wouldn’t go down without a fight. That evening, the U.S. Marshals assembled on campus became accosted by a crowd of about a thousand people. Most of them were students who felt provoked by the heavy-handed Federal presence on their campus. The mob began to harass the U.S. Marshals at 7:25 PM local time. Over the next few hours, two thousand more agitators made their way onto the Oxford campus and soon the harassment swelled into a full-on riot.

Faced with such a large and violent mob, the 500 U.S. Marshals proved wholly unable to contain the rioters. Those angrily protesting the Marshals’ presence pelted them with rocks, bricks, and small arms fire. The white mob also set cars on fire and damaged university property. The Marshals defended themselves as best they could with tear gas...until they ran out of it. With the rioting growing worse by the hour, President Jackson ordered four thousand motorized infantry troops to head to Oxford and restore order there. Having intervened militarily in the Dominican Republic the previous spring, Scoop was not about to look inept dealing with violence within his own country. When they arrived at Ole Miss in the pre-dawn hours of September 21st, the rioters turned their assault on them. The commanding general barely escaped getting killed when his staff car was surrounded at the university’s gate and set on fire. The general and his other passengers were luckily able to escape the burning car and make the 200 yard dash to safety. Gradually, the arriving soldiers were able to establish control over the campus and force the mob to dissolve. When the rioting ended that Friday morning and an uneasy peace had returned, 166 U.S. Marshals and 40 soldiers were wounded. Grimly, two men had been killed during the rioting:

- Foreign-born journalist Paul Guihard, who was covering the event for the British tabloid newspaper “The Daily Sketch”. His body was found behind a building with a gunshot wound in the back of his head.

- Ray Gunter, a local white jukebox repairman who had come to the campus merely out of curiosity. He was found with a gunshot wound in his forehead.

After spending the weekend at Ole Miss making sure that the U.S. Marshals would be adequately able to protect Meredith while he attended his classes, Ledyard returned to Washington on Monday, September 24th. He regarded Ole Miss as “Mission Accomplished”: he had stared down Barnett and forced him to desegregate the University of Mississippi. In doing so, the Attorney General had demonstrated to the South that resisting Federal court orders was futile. National reaction to The Enforcer’s handling of Ole Miss was mixed. Several Southern newspapers vilified Ledyard as being a modern-day William Tecumseh Sherman: a Northern brute who assaulted the Southern way of life without mercy. On the flip side of the coin, Ledyard was hailed as a hero by civil rights supporters for his firm and resolute leadership in getting Meredith enrolled. According to an editorial in “The Washington Post”, the Attorney General had handled the situation in Mississippi better than anyone else could have handled it. Some people even put Ledyard’s name forward as a Republican Presidential candidate in 1964. In his characteristic blunt style, The Enforcer shot that idea down:

“I have never had the desire to be President of the United States. I will never be President of the United States. So stop wasting your time thinking about me becoming President of the United States.”

Despite having the Federal Government on his side, Meredith wasn’t completely accepted by his peers during his two semesters at the University of Mississippi. While some white students did accept him as an equal, others harassed Meredith every chance they got – even though the U.S. Marshals guarded him twenty-four hours a day. For example, students who lived in the dorm room directly above Meredith’s would bounce basketballs on the floor at all hours of the night. He was also subjected to isolation. Whenever Meredith walked into the cafeteria to get his food, other students would turn their backs on him and steer clear of whichever table he sat at. Having gotten this far, Meredith endured this treatment and graduated on August 18th, 1963 with a degree in political science.

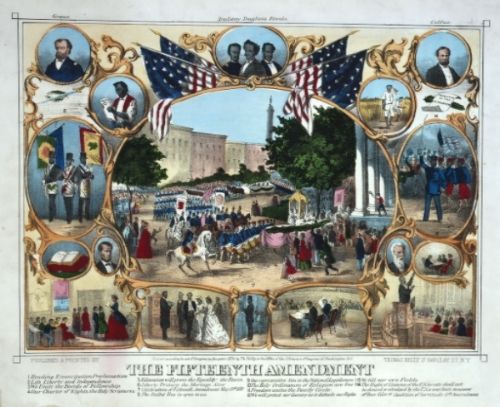

The desegregation of the University of Mississippi in September 1962 became a watershed moment in the fight against Southern racism. Southern whites, so used to being able to deny blacks their rights as American citizens with impunity, now found that the tables had turned. Having once condoned the Jim Crow system, the Federal Government was now moving aggressively in dismantling it piece by piece. By forcing Ole Miss to register James Meredith, the Jackson Administration had demonstrated to African-Americans that they had a powerful ally in their fight against segregation. This in turn emboldened blacks to step up their campaign to ultimately eradicate Jim Crow from all walks of life. Ledyard’s actions had told white Southerners in the clearest manner possible that the days of the Federal Government accommodating their attitude against blacks were over. These Southerners would grow violently desperate to hold back the rising tide of racial progress. Thus Ole Miss had set the stage for what would follow in 1963.