It lives! I half suspected this was another Jape abandonment and am delighted to see you return.

A surprisingly good peace deal for Italy, I had wondered if Lanza would be able to limp on for a few more years on the strength of it. Instead he managed to find a new and exciting way to finally kill his career. He really wasn't very good at the whole running a country thing was he?

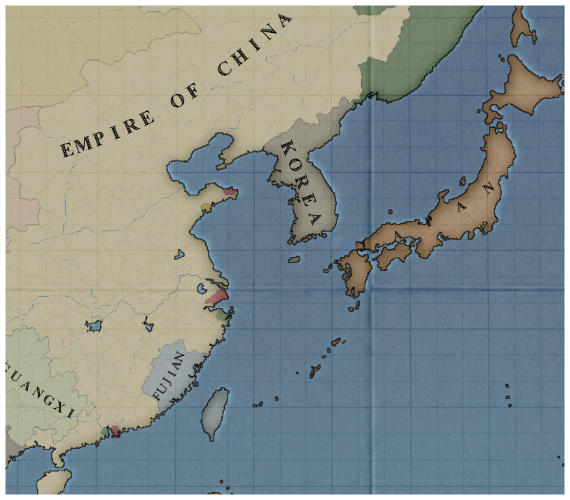

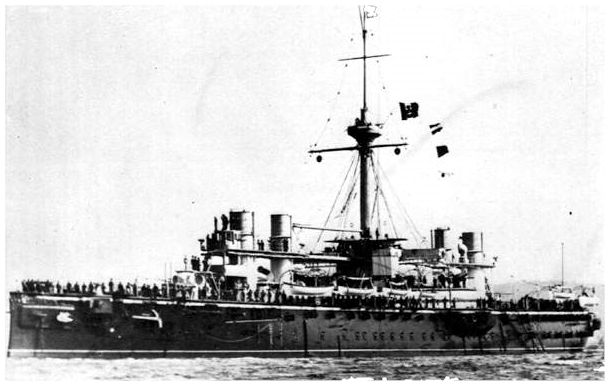

A Franco-Ottoman friendship would indeed be worrying for Rome, but at least it isn't a formal alliance (yet?). It will complicate the choices, Italy can't just rebuild her fleet as she also has to keep an eye on the French across the Alps. Fortresses on the Alps and Battleships on the slips?

A surprisingly good peace deal for Italy, I had wondered if Lanza would be able to limp on for a few more years on the strength of it. Instead he managed to find a new and exciting way to finally kill his career. He really wasn't very good at the whole running a country thing was he?

A Franco-Ottoman friendship would indeed be worrying for Rome, but at least it isn't a formal alliance (yet?). It will complicate the choices, Italy can't just rebuild her fleet as she also has to keep an eye on the French across the Alps. Fortresses on the Alps and Battleships on the slips?