The Palestinian Wars 1301-1320

The twenty year conflict in the Levant initiated by Niv II’s decision to forcefully press his claim to the Kingdom of Jerusalem progressed through a number of different stages as it escalated into a matter of Assyria’s very existence. In the first part of the conflict, the Assyrians faced down the Crusader lords of Outremer. Benefiting from much greater numbers and a unified leadership under the talented generalship of their King, the Assyrians made strong gains – capturing a number of fortresses east of the Jordan River and placing Jerusalem and Jaffa under siege.

The tide of the conflict started to change after German forces began to arrive in the Levant from around 1303, and especially after the Kaiser himself landed at Beirut in 1304. The Germans, greatly outnumbering the Assyrians, captured Acre, relieved Jerusalem and Jaffa and reclaimed most of the Jordan Valley, all the while sparing with the Assyrians leading to heavy losses on both sides.

While the Germans could field more men, and had a steady stream of reinforcements from Europe that the Assyrians could not match, the course of the conflict began to bend in Nineveh’s favour in the face of a number of key victories on the field of battle that Niv led his men to. Fighting was attritional and costly, but within a couple of years the momentum of the German advance had been halted and by 1307 the Assyrians were beginning to make gains – pushing back into the Jordan valley, recapturing Acre and most importantly of all bringing Jerusalem under siege once again. Assyrian prospects were further enhanced when the Emperor Dietrich passed away as a break out of cholera in Jaffa ripped through his army. His successor Friedrich, far away in Europe, was less focussed on the Palestinian conflict, and as such limited the resources being sent to the long campaign in Outremer.

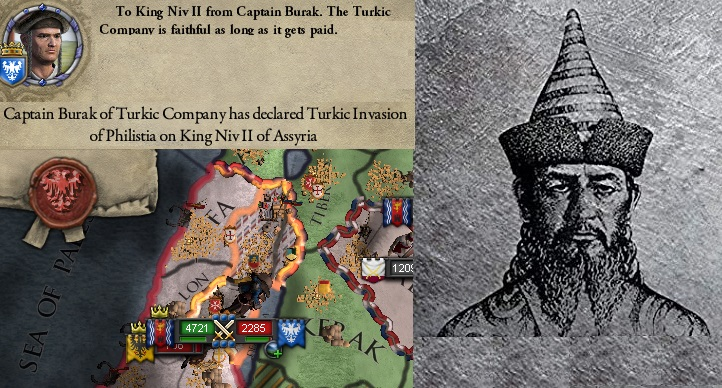

It was during this siege of Jerusalem that relations between the crown and Cumans finally broke down. Having maintained a testing relationship with the monarchy ever since their first arrival in Assyria decades before, the Cumans had been particularly reluctant to become involved in a great conflict with their Catholic co-religionists in Palestine. Notably, they had been alienated by an increasingly anti-Catholic Assyrian attitude and the very heavy losses their forces had sustained. These concerns had been papered over with the reward of ample payment and loot, yet with the Assyrian state’s coffers completely emptied by the costly conflict, the Cuman’s were left unpaid, relying only on the promises of future rewards. As the Assyrian army was afflicted by food shortages and disease during its long siege of Jerusalem, the Cuman Khan Burak turned against his King and raised the flag of rebellion – threatening to take the Holy Land for himself.

With the Cumans making up around a third of the Assyrian army, this was a near mortal blow. While Niv fought the Cumans off, he lacked the numbers to maintain the siege without them and withdrew back east of the Jordan river. Meanwhile, the Cumans were able to withdraw north and capture Acre – attracting some support from the local Latins as they established a stronghold from which they launched debilitating raids throughout the Levant. During this lull in the fighting, the Assyrians were able to gather fresh troops from Mesopotamia for a renewed attack – returning to besiege Jerusalem once more and finally capturing the city in 1312. Shortly thereafter the Holy Roman Emperor agreed to a truce – dividing the Holy Land between German territories in the Lebanon and Palestinian coast and Assyrian lands in the interior, including Jerusalem itself. Notably, Niv agreed to renounce the title King of Jerusalem, in claim of the less ostentatious King of Philistia.

While Niv and the Assyrians appeared to be on the precipice of a lasting victory, word arrived that a new threat was tumbling down the Syrian coast from the north. Burak Khan, holed up in Acre, was well aware of the impending threat as the conflict between the Germans and Assyrians wound down and had sent a messenger to his ethnic kin in Anatolia seeking allies and aid. Cuman Anatolia had retained the febrile instability of the Steppe, with many factions squabbling for power among one another. One of the great tribal leaders of the region, Tunga Khan, saw in his compatriots’ plea an opportunity to escape a weak position in Anatolia and strike out to conquer new lands. He would therefore lead not only fifteen thousand riders, but wagons of women and children, herds of animals and thousands of horses, southwards towards the Holy Land. As Tunga and Burak united, they were instantly the greatest power in Palestine – forcing Niv into a retreat back to Damascus yet again and capturing Jerusalem in 1313. With near total control over the region, the two Khans would set out to build a Cuman Kingdom in Philistia, while regularly driving deep into Assyrian territory, harassing Niv’s armies and threatening to attack locations as far east as Mesopotamia.

Assyria’s struggles with the Cumans convinced others of its weakness in the Levant. While the Cumans consolidated their grip in Philistia, two new threats arose. In the south, Shia Arab tribes from the deserts south of Palestine invaded Assyrian territory – capturing the fortresses of Kerak and Monreal to the east of the Dead Sea and raiding far to the north. As King Niv sought to address this threat, he was lured into the greatest military disaster of his long and bloody reign. The Assyrians were expertly outmanoeuvred by the Muslims, who isolated the Christian army from all key sources of water before pouncing upon their foe – almost completely destroying the Assyrian army. The Shia captured the Crown Prince, Isho, on the field while Niv himself barely escaped to the north with his life. Over the following years, although their gains were undermined by tribal infighting, the Shia pushed on to capture Amman and enter into a struggle for the Holy City itself against the Cumans.

A further threat came from the Druze. This small, somewhat esoteric, ethno-religious group had its origins in an offshoot in the eleventh century Shia Fatimid Caliphate. After its followers were forced to flee Egypt, they settled in the region to the east of Damascus, the Jabal al-Druze. Since then they had lived mostly in peace under Muslim and Christian masters alike, yet now they had sensed an opportunity to strike out for independence and in 1314 rose up to occupy their homeland and move against the great city of Damascus.

By now, King Niv cut an isolated figure. His wars had heavily indebted his realm, limiting its opportunities to further finance the war, it had suffered horrendous manpower losses that could not be easily recouped, its most effective military force of the past several decades – the Cumans – were in arms against it, and its exhausted nobility and martial elite were losing patience and faith in their King’s ambitions. A reprieve, of a sort, arrived in 1316 with another crucial battlefield triumph. At Qasr Amra, not far from Damascus, the royal army, outnumbered two to one, crushed the Druze on the open field, scattering their force and defeating their rebellion once and for all. Crucially, this ensured that the link between the Assyrian Levant and Mesopotamia remained open and revived Niv’s wavering military reputation.

Following the victory over the Druze, Niv left his army in Damascus and returned to Nineveh. There he sought to calm the faltering support of his nobility – many of whom were demanding that the King abandon his conquests in Palestine in order to avert graver disaster. However, his real target was the Church and Patriarch Tavish III. The Nestorian religious hierarchy had maintained an ambiguous relationship to the Palestinian Wars, the lengthy conflict, predominantly with Catholic powers, over the Holy Land. Importantly, they had maintain the bar against members of Nestorian holy orders from taking up arms against fellow Christians. Lacking the manpower to reclaim suzerainty over Palestine on his own, Niv hoped to tap into the last major unscathed source of soldiery open to him – the Order of Saint Addai. The Patriarch’s demands were significant – grants of land in Mesopotamia, greater legal and tax privileges for the Church in Assyria, support for religious missions to maintain links to the St Thomas Christians in India and ecclesiastical control of the most important holy sites in Jerusalem and its surrounds. Niv agreed to everything and in return, was given the men he asked for to march west one last time.

Replenished with the men of the Order, Niv set out from Damascus in 1317 for a final do or die campaign against the Cumans. Despite incurring very heavy losses, his men scored key victories that put the Cumans into retreat and allowed the Assyrians to bring Jerusalem itself under siege. With the Turkic armies just as weary as the Assyrians, after the Holy City fell in 1320, the Khans Tunga and Burak, although still controlling the better part of Philistia, was finally ready to negotiate. Accepting the end of his dream of a Cuman Kingdom in the Holy Land, Tunga secured new rights for settlement across the Assyrian domain. While the existing Cuman population of Assyria was allowed to return to their settlements around Lake Urmia, the newly arrived wave of Anatolian Cumans were granted land rights in Palestine and northern Mesopotamia – further swelling the growing Turkic component of Assyrian society. Moreover, they would resume their previous status under the military service of the Assyrian crown. In exchange, they swore allegiance to Nineveh as their overlord.

With peace now secured with their main foe, the Assyrians and Cumans joined together to sweep the Shia back into their home territories before the end of the year. Two decades after first inheriting the crown of Jerusalem, Niv’s division of Palestine was now complete.