Tsaritsa Artanis and the Ciliarch Kephradates Terter

Tsaritsa Artanis (1462 AD – 1500 AD)

Artanis ascended the imperial throne in 1462 AD at the age of thirty-four, laden with the uncertainty and paranoia born of a lonely childhood and maternal neglect. For her entire girlhood, she had lived in the half-shadows of court intrigue, with a mother dismissive of her existence, and no siblings to share her burdens.

These early insecurities were well known at court, and gave rise to fears of a cruel reign. Her earliest steps were hesitant. She feared conspiracies in every corridor. The pretender Darius Achaemenid-Mezeshka had proclaimed himself the rightful sovereign and commanded no small number of sympathizers among the nobility. In response, she created a formidable network of informants, the All-Seeing Eye - a system whose very name evoked dread among courtiers. In these first years, Artanis’s paranoia manifested in cruel purges of “traitors,”. Tales describe how entire families vanished after a single report. Many believed the Empress would reign as a vicious tyrant for the rest of her days. Yet, a remarkable evolution lay ahead. Over the next thirty-eight years, she would evolve into a capable, at times audacious, Empress, forging new diplomatic ties and radically modernizing her armies, even as personal tragedy haunted her family.

Artanis would shape the All-Seeing Eye towards a more righteous purpose. The meticulously gathered reports both anchored Artanis’ confidence and guided her policies. No longer in the dark about the machinations of corrupt mayors or rebellious nobles, she methodically rooted out threats and consolidated her authority. Over nearly four decades, she fashioned a naval force that would shape Mediterranean politics, reworked her empire’s medieval armies into disciplined contract soldiers, and championed the cause of the urban poor striving to learn crafts once locked behind ancient guild walls. The metamorphosis was neither simple nor sudden, but an evolution of an Empress that was learning what it meant to rule.

Breaking Down the Old Order

Once her personal safety was secured, Artanis’ attention drifted to the moribund economy. One of her ministers whispered that “our guilds function as personal fiefdoms for a select few.” Indeed, entrenched guild masters ruthlessly kept out new blood. Apprenticeships went to the friends and favoured servants of select noble families or personal favourites. The empire’s largest towns – Achaemedia, Thessaloniki, Ragusa - might have thrived in commerce, but skilled labourers were starved of a chance to grow.

Artanis recognized a political opportunity. She championed the Kefaliyas (merchant-mayors and local administrators) who insisted that new trade charters, free from guild monopolies, would enrich the towns and expand the tax base. At first, the old guilds fought back, calling the Kefaliyas “nestlings of chaos” who would destroy centuries of tradition. But the Empress sided with the new generation.

She authorized charters that allowed peasants to become apprentices, once a far-fetched notion. These new crafters could open modest shops or band together into more flexible “work cooperatives,” paying taxes directly to the crown rather than owing feudal duties to lords.

Artisans from weaving to glassblowing sprang up in neighbourhoods that had previously been impoverished. An official census in 1480 noted an unprecedented increase in recognized apprentices. Peasants’ families migrated from farmland into the city’s bustling wards to try their luck in nascent trades.

It shocked the older powers. But Artanis, buoyed by intelligence from the All-Seeing Eye, quashed the boyars’ attempts to sabotage or hamper the new system, proving that her fearsome secret police did not merely punish treason: it enforced her will for reform.

Commanding the Seas

The Empress’s next vision: command of the sea. A single modest fleet had guarded the empire’s coasts for generations, never contending with the realm’s greatest threat – dominant maritime states in Latin Europe or the rising powers in the Levant. Artanis refused to stay a bystander.

She commissioned the new flagship, named Artanis after herself – a magnificent war galley with heavier prows, advanced rigging, and a formidable contingent of marine crossbowmen. Then, with guild reforms accelerating urban wealth and the empire’s coffer swelling from trade duties, she authorized the building or refitting of dozens more ships:

Artanis effectively “escorted” caravans across the eastern Mediterranean, forcing the Islamic states of the Levant to open ports and fix their customs rates beneficially. Beyond this muscle-flexing on the seas, she endeavoured to forge an alliance with the Shia Imamate of Jerusalem and the Eranshahr in the Caucasus. On paper, the notion of a Christian Orthodox Empress allying with Shia powers unsettled conservative bishops, but Artanis was determined: securing access to Levantine markets and ensuring the empire’s eastern frontier remained peaceful demanded a convergence of interests. Diplomatic missives to Jerusalem and Eranshahr combined appeals to both faith and trade, culminating in beneficial treaties that bolstered the cross-border exchange of goods – grain, dyes, and especially precious metals. The added bonus that she established an entente to hamper the dreaded Ottomans of Anatolia was an important consideration of the strategic value of these alliances.

By 1485, foreign captains recognized that no maritime competitor in the eastern sea could match the Achaemenid navy’s scale and discipline. Where once pirates preyed easily upon merchant ships, the navy’s galleys now patrolled crucial shipping routes. The empire, at last, shaped Mediterranean commerce.

Victory and Blood in North Africa

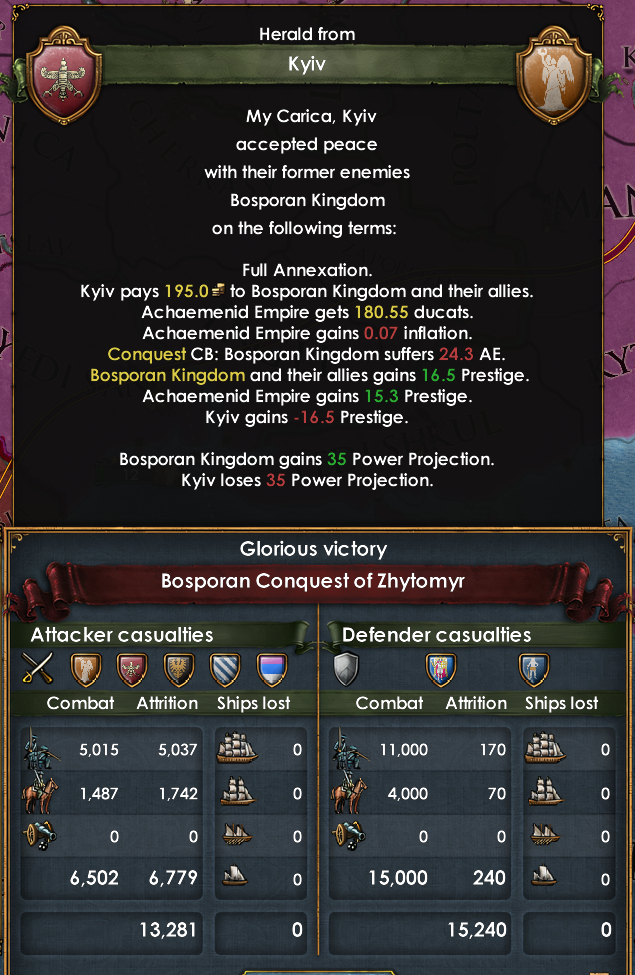

Embarking on her largest military undertaking, Artanis set out to unify and strengthen her outposts in North Africa, particularly around Tunis and the old African coastal enclaves. Her collision with Morocco – called Hadrametum in old imperial records required careful engineering. Local Christian families, most notably the Selges held more sway here than the Imperial throne. This would all change in the 1470s as she provoked the local Emirs under the banner of Morocco (or “Hadrametum” in old imperial parlance) into a border dispute. With that pretext, she would bring the existing territories more cleanly into the imperial embrace and launch a formal campaign into Morocco to “defend her loyal Constantinian subjects”.

1476 was a year of bitter, punishing war. The imperial forces marched confidently, but the sultan’s cavalry ambushed them at oasis of Ourgia. Surviving diaries recall how entire ranks were cut down – 11,000 imperials and 15,000 Moroccans died. Artanis’s reliance on short-term feudal levies was already being challenged with supply lines being so stretched and many local levies lost in the first months. Failing morale demanded fresh troops, so Artanis turned to the Free Company and the Kastrioti. These hardened sellswords, placed under the overall command of the cunning Strategos Mihail Krum, hammered the Moroccans, culminating in the capture of Fez.

Krum skilfully manoeuvred around Moroccan positions. After Ourgia’s horrors, it was the mercenaries, temperamentally suited to such a lengthy war, who spearheaded the city sieges. The final capitulation of Morocco, formalized with the capture of Fez, turned the region of Tunis/Africa into an imperial stronghold. Victorious, she absorbed the Moroccan coastal provinces in Tunis, notably the strategic island of Djerba. Naval bases sprouted along that coast, the local fortresses were upgraded, small harbours were dredged, and imperial governors established watchtowers along caravan routes to deter raids. Henceforth, references to “the fortress of Africa” would denote both the physical walls along the coast and the empire’s relentless naval patrols.

Soldiers of Crimson and Gold

After this brutal war, returning to standard medieval levies seemed pointless. Artanis chose to hire mercenaries permanently, with year-round pay, lodging, and a contract forbidding private lords from meddling. Although it strained the treasury, it gave her a loyal, professional backbone. The arrangement bore dividends. Mercenary captains swore contracts that included strict codes of conduct, limiting the petty pillaging and abuses that had plagued medieval musters. This partial professionalization laid a foundation for the empire’s eventual modernization of warfare in the century to come. Artanis’s own words ring prescient:

“Our soldiers should not vanish at harvest time.” On her watch, they did not.

Regions along the empire’s frontier, particularly Serbia and North Africa, hosted paid garrisons year-round, reducing local revolts and offering peasants greater security. Nobles grumbled that mercenaries, rather than traditional feudal cavalry, formed the empire’s backbone. Disputes with Artanis over the shrinking levy obligations would echo into her final years when her most trusted advisor attempted to restore noble privileges.

The Ottoman Frontier

Throughout her reign, Artanis coveted the reconquest of Achaemenid territories and warily eyed the Ottoman Empire, which had entrenched itself in Anatolia. She found local successes: subduing Thessaly and Athens, then forming a vassal princedom but attacks against her vassal states in Northeastern Anatolia had eroded her ability to project power into Asia. Anatolia itself had become fully Ottoman save for a toehold around Nicaea.

The empire recognized the near-impossibility of retaking the Byzanstani heartlands, given the Ottomans’ firm hold. Artanis resorted to forging alliances, trusting the Imamate of Jerusalem or Eranshahr to check Ottoman ambitions on their own borders, albeit rarely with decisive results. The Ottomans completed a fortress on the Chalcedonian coast, dominating the Bosphorus shipping route. As she turned her eyes back to the Bosphorus, the Ottomans were entrenching themselves in Anatolia. Their new fortress, Rumeli-Hisari, dominated the strait. They forbade Christian ships from passing unless they paid tolls and Artanis found it essential to station a segment of her new fleet in these waters, ensuring that imperial convoys could still pass unmolested.

She consoled herself by capturing Thessaly and Athens from the collapsing Macedonian state, merging them into a new “Princedom of Trebizond,” ironically named to evoke the empire’s old ambitions in Asia Minor. She declared symbolic victories, but the unstoppable expansion by the Turks haunted her.

The Ciliarch’s Adventurism

By the 1490s, the once-paranoid Empress was old and less attentive. She placed near-complete trust in Kephradates Terter, her Ciliarch. Cut from a more traditional cloth, Terter sought to roll back some of Artanis’s liberal reforms and placate disgruntled nobles.

With peasants embracing new freedoms, many old families felt shortchanged. Over decades, they had quietly formed alliances, waiting for the moment the Empress’s vigilance wavered. Kephradates himself had grown increasingly comfortable dipping into the imperial treasury for his personal enrichment and that of his cronies.

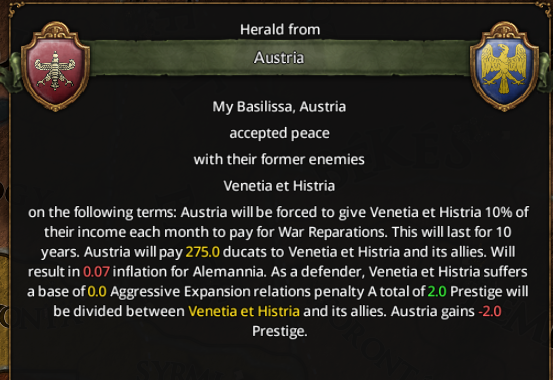

In 1496, at the urging of powerful lords, Terter launched an aggressive war against the Italic-Istrian duchy of Venetia et Histria, presuming their city-state allies in Italy would not stand a chance against the Empire and a quick strike for loot and plunder. Instead, the formidable Germanic Kingdom of Alemannia answered their call, framing the attack as an assault on rightful Christendom. In a stroke of penmanship declaring the war, Kephradates had reawakened the memory of the evil Empire in Western minds that Artanis and her mother had tried so hard to put to bed.

In early 1496, Achaemenid banners advanced across the mountainous borders of Istria, smashing local militias in quick, violent clashes. For a brief moment, the gamble looked to pay off: fortress after fortress fell. Yet the impetus soon changed. By summer, the forward imperial columns encountered something new – a trained Alemmanian army that had forced a corridor through Tyrol, arriving with startling speed. The armed might of King Guntimer III collided with the advanced but scattered Achaemenid soldiers in the foothills of the Alps.

Cannons at Wien

The empire’s ally, Austria, found itself in the crosshairs of Guntimer’s army. Their capital, Wien, was ringed by stout walls but had rarely faced modern artillery. Observers from the era spoke in awed terms of “thunder tubes,” or early cannons, monstrous to behold yet more accurate than the rudimentary bombards known in the east. Meanwhile, Mihail Krum, arguably the greatest living Achaemenid commander, hurried northward to break the siege.

The Catholic alliance unleashed newly perfected cannons – huge and unwieldy, but devastating to massed infantry charges. Krum’s 75,000 men faced withering artillery fire; half did not return. By twilight, Achaemenid lines had bent. Krum judged that continuing risked annihilation and thus led a disciplined withdrawal. Modern historians speculate he saved half his army by choosing retreat over hopeless assault. But Austrian watchers on Wien’s ramparts saw the empire’s might melt away. Within weeks, the city surrendered, and Austria itself agreed to humiliating terms, paying war indemnities to end the ravaging.

With Austria out of the picture, the Achaemenids faced a bitter truth: they stood alone against Alemmania’s unstoppable momentum. The imperial generals dreaded a prolonged campaign in alien terrain, far from supply lines, with an adversary both emboldened and armed with advanced artillery.

Burning Gold, Raising Armies

In Achaemedia’s palace, Kephradates grimly allocated emergency funds from the treasury to recruit more mercenaries. Fields of Bulgarian farmland were practically taxed into oblivion to fill war chests. The peasants, enthralled by Tsaritsa Artanis’s earlier boons, now found their produce requisitioned. Entire hamlets faced conscription as iron-limbed mercenaries demanded quarter and pay.

Many soldiers felt no personal quarrel with the Catholics or the statelets of northern Italy. A fresh wave of desertions began. The All-Seeing Eye, once used to quell internal dissent, found itself chasing down rebellious conscripts. And still, Kephradates demanded a continued push, unwilling to relent so soon after triggering this calamitous war.

A year after Wien, the imperial cause seemed to be verging on total collapse. Alemania marched through the Danube basin, threatening to carve right into the empire’s Balkan heart. Then Strategos Mihail Krum, recovering from the blow at Wien, found a defensive line in Hum – a rugged region of high passes and ravines.

The First Battle of Hum (1498)

Gaudulf von Tegernsee, leading the Alemmanian vanguard, attempted to bring his fearsome artillery into these narrow passes, a near-impossible logistical feat. Krum’s scouts raided relentlessly, sowing chaos. The empire’s forces outnumbered and battered, still refused to offer a pitched confrontation. Krum skillfully withdrew further up the mountainside whenever the pressure became too strong, forcing Gaudulf’s cannons to inch forward precariously. The cost to Gaudulf was ruinous: half his cavalry perished in disorganized skirmishes, and a fifth of the artillery was lost or abandoned on untraversable trails. Though Krum’s men also suffered in these cold, bleak highlands, the near stalemate gave new hope to the empire – clearly, the gunpowder advantage was worthless in pass-fighting if Krum controlled the pace.

The Second Battle of Hum (1499)

Now Gaudulf, smarting from the prior fiasco, decided to subdue the fortress of Kjluc, a smaller citadel. He assumed Krum had withdrawn to refortify deeper behind the mountains. In truth, Krum had left behind a token Trebizond contingent as “bait” inside Kjluc. Emboldened by previous partial successes, Gaudulf put his cannons to work reducing the fortress walls. At that moment, Krum’s main body descended from hidden ridges, sealing off the mountain roads behind Gaudulf. With the fortress in front and Krum’s host behind, the Alemmanian lines buckled. Caught in cramped defiles under the unrelenting arrow and crossbow fire, Gaudulf’s men struggled to pivot their artillery. The second day saw half the Alemmanian army lost to casualties or desertion. Gaudulf himself sustained injuries in a final, desperate breakout attempt.

Krum’s triumph in the mountains staved off immediate collapse and forced King Guntimer of Alemmania to consider negotiation. Meanwhile, the empire’s homeland was near to ruin. Pillaging had swept across the Danube region – grain fields burned, entire villages uprooted. The Venetian provinces turned resentful, under a savage occupation.

A Pyrrhic Victory

Kephradates realized he needed to sue for peace while claiming a rhetorical victory. The Catholic side likewise had exhausted its impetus, reeling from the shock of the second Hum fiasco. The peace terms were in Achaemedia’s favour but the gains hardly matched the misery left in the war’s wake.. Officially, Venetia was integrated as a vassal, paying homage to the Tsaritsa. Some outraged Italians labelled it “the start of the Khodan invasion”. King Guntimer, mindful of Gaudulf’s defeat, paid out an enormous indemnity of eight hundred talents of silver.

The empire returned to a battered domain with a near-emptied treasury, ravaged farmland, and a disillusioned populace. Noblemen boasted that they had gained heroic glory in Europe, but many peasants lamented, “Of what use is Venetian gold when half our households are fatherless?”

With the Ottoman invasion of Eranshahr shattering Artanis' entente model, there was little choice but to sign a compromised peace. Venetia et Histria became an Achaemenid vassal, and the Germanic powers were dealt with.

A Waning Tsaritsa

Throughout this catastrophe, Tsaritsa Artanis, once known for her incisive mind, scarcely grasped the scale of the calamity. Ageing and drifting in mental acuity, she relied entirely on the Ciliarch’s word. The few times she appeared at council sessions, she wore a distant look, speaking softly of expansions in the old days and new opportunities at sea, oblivious to the tears of local farmers who’d lost everything.

In 1500, as the empire bled from within, Artanis slipped away from life, her final hours spent in confused calm. She never realized how precarious Kephradates’s war had rendered her dominion, nor the extent to which the empire’s greatest general, Mihail Krum, had salvaged the realm at an unthinkable cost in lives.

Artanis’s personal tragedies paralleled the empire’s. Her eldest son, Dawud, died in his twenties of a wasting illness. It is said that from that day, her eyes lost their sharpness; she never again harangued or second-guessed the generals in the same fierce manner. She named her daughter, Kyriake, as her successor. Courtiers whisper that the princess was far more interested in sword duels and lavish feasts than governance, but the line of succession was at least secure.

Artanis died in the spring of 1500, leaving to her daughter a battered empire yet one still standing. The mercenary tradition endured, half the army being professional companies sworn to the throne. The navy, the fruit of her toil, remained the envy of many. And the peasantry, having tasted new freedoms, would remain a stubbornly independent force in the empire’s local economies.

The Paradox of Artanis

Historians continue to debate whether to remember Artanis for her harsh early years – marked by the All-Seeing Eye and swift punishments – or her mid-reign brilliance in modernizing the economy, forging a supreme navy, and pioneering a professional army. While her final years saw the empire nearly wrecked by an ill-conceived war, no one could call her reign dull. By her own measure, she once wrote to a foreign ambassador:

“I was born powerless and afraid. I will not die cowering in a corner. Let the world judge me by the empire’s vitality, not by the wrack of malice.”

In the end, that empire was indeed alive, armed with war galleys, brimming with urban crafts, and learning to rely on standing armies more than feudal muster. Artanis left a realm torn by foreign campaigns but also glimpsing modern governance and mercantile freedoms. She remains a singular figure – the paranoid Empress who conquered her terrors, marched against the end of feudalism, then watched, too frail and trusting, as her ministers marched thousands to battle in the empire’s name. When she closed her eyes in 1500, her realm stood on the cusp of the 16th century: precarious positioned as a new era of colonialism would see the rise of Western Europe to challenge the old order.