A Very American Nightmare – The 1936 Presidential Election

Democracy depends upon the willingness and ability of millions of people to come together in common values, institutions and brotherhood. As the results of the Presidential election that year would show, by November 3 1936, the citizens of America had ceased to be able to even begin to comprehend one another.

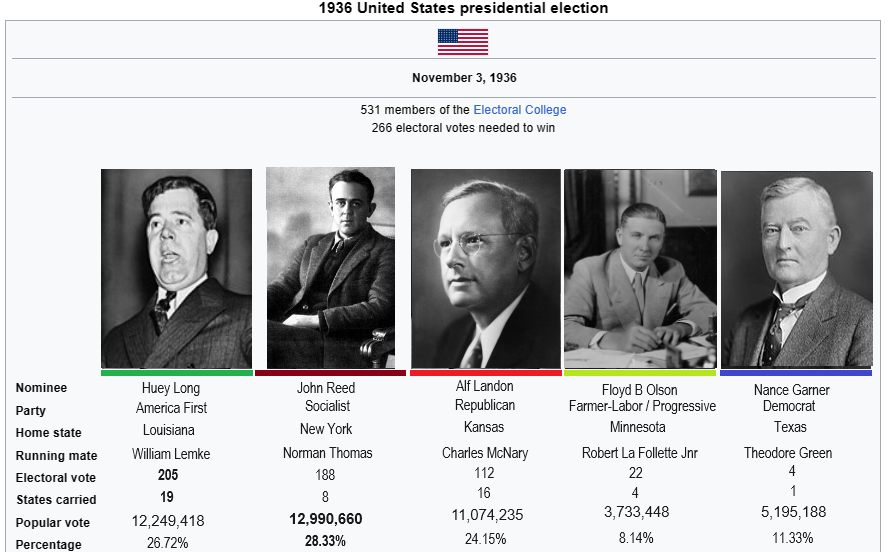

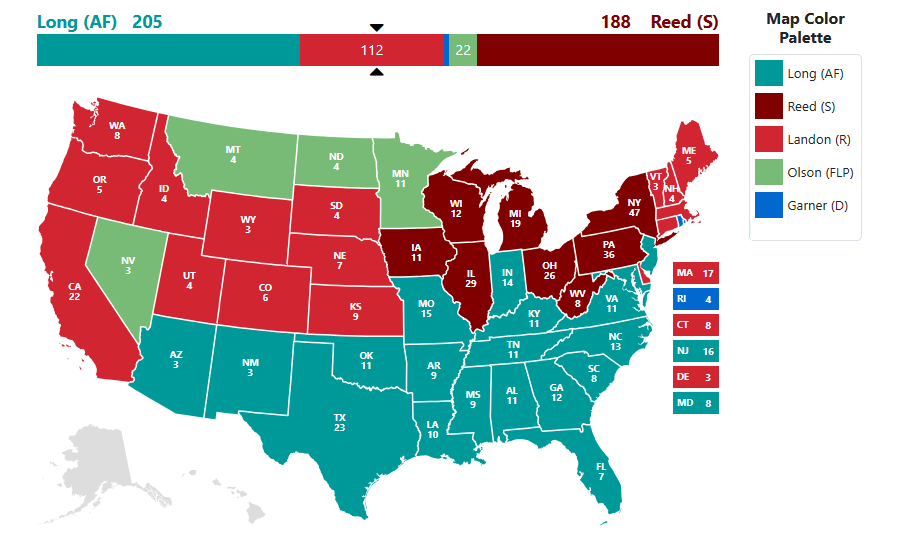

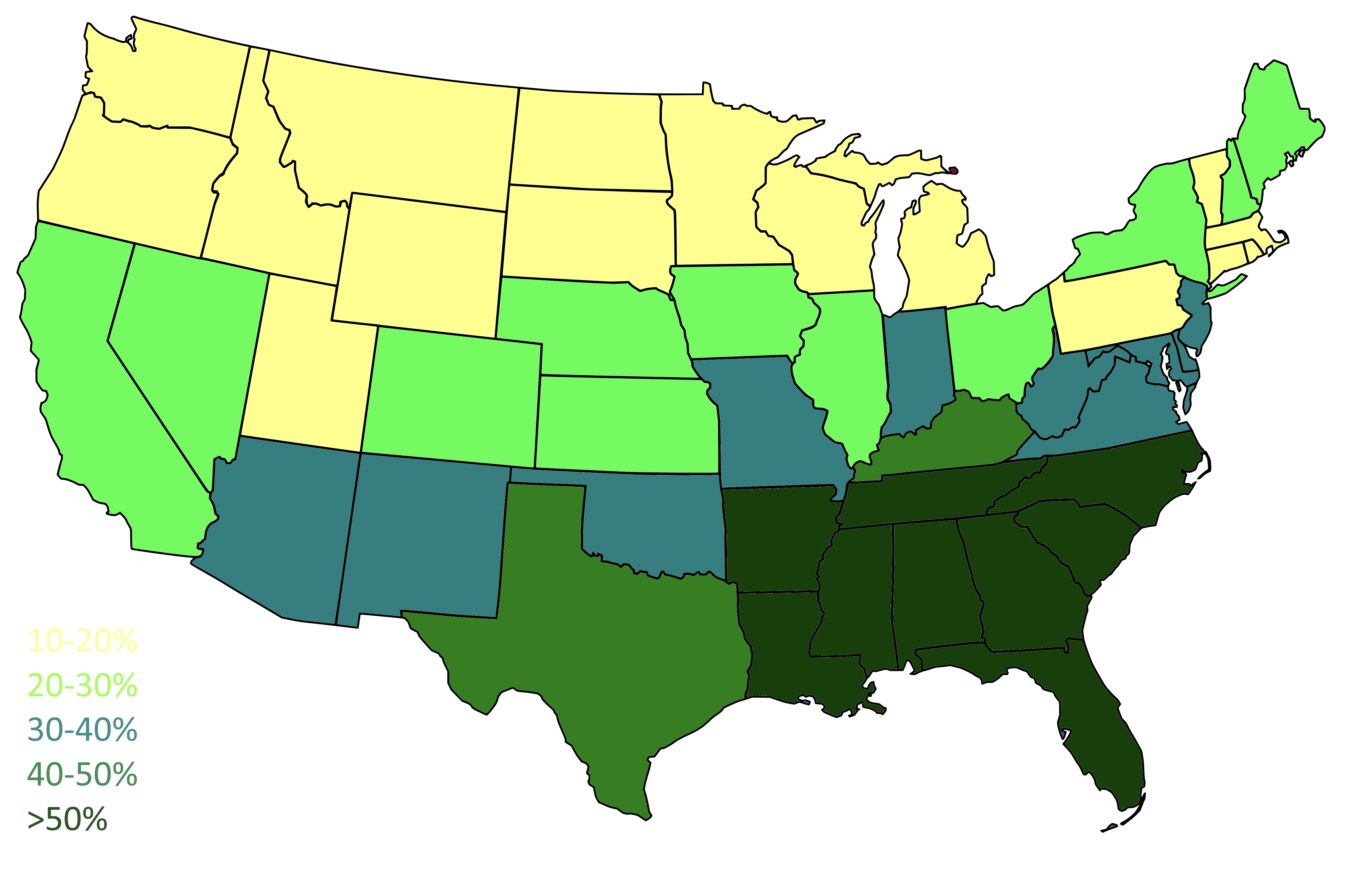

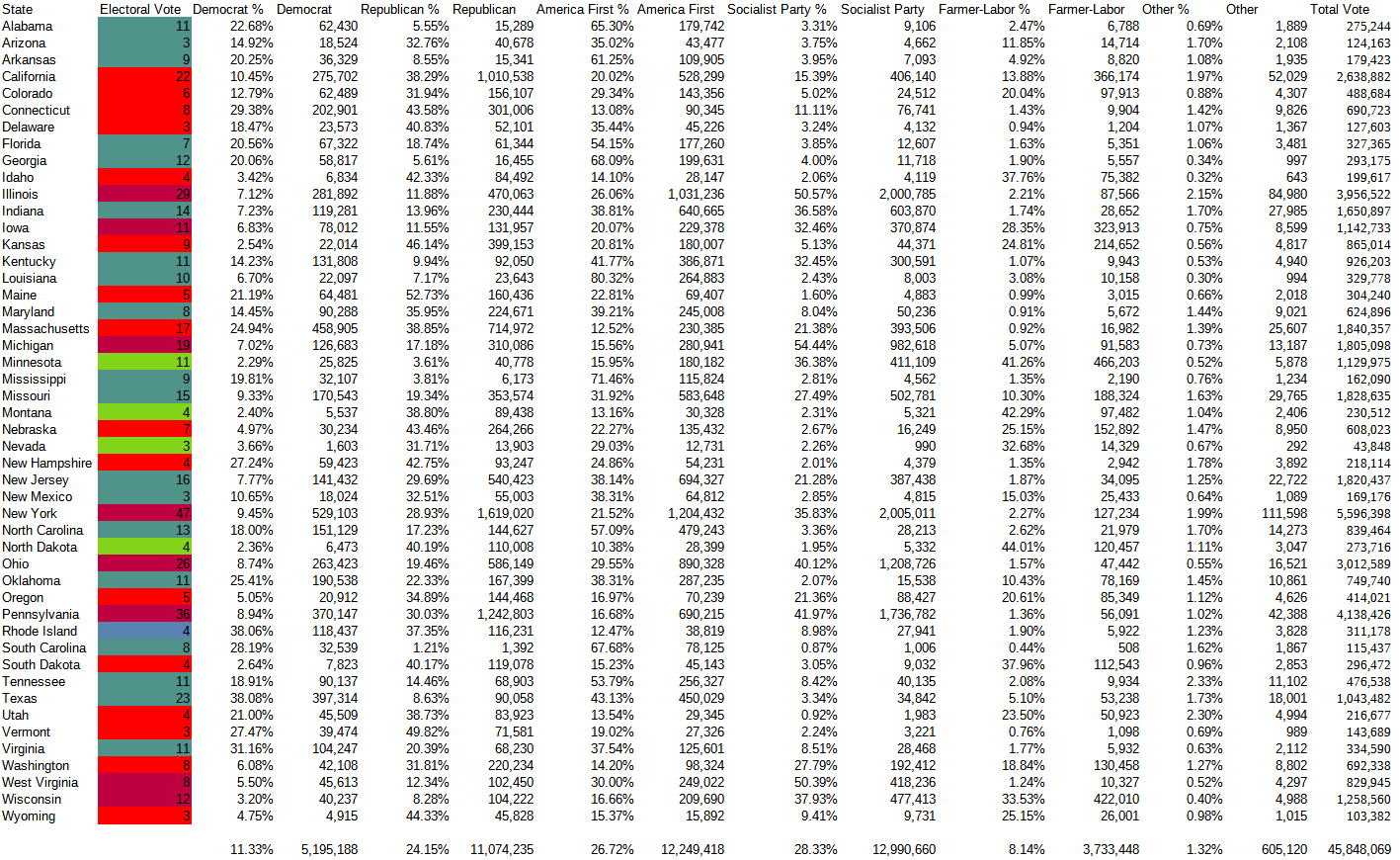

The results were as catastrophic as they were dramatic. No fewer than five major candidates had spent the preceding months criss-crossing the nation in a heated and periodically violent campaign, with each of them securing victory in at least one state and carrying millions of votes. However, not one of them would succeed in mustering as much as three tenths of the popular vote or come anywhere close to a majority in the electoral college. Results were also highly regionalised, with many parties uncompetitive in large parts – and totally anathema to voters there – while having concentrated support elsewhere – contributing to the splintering of the American public consciousness.

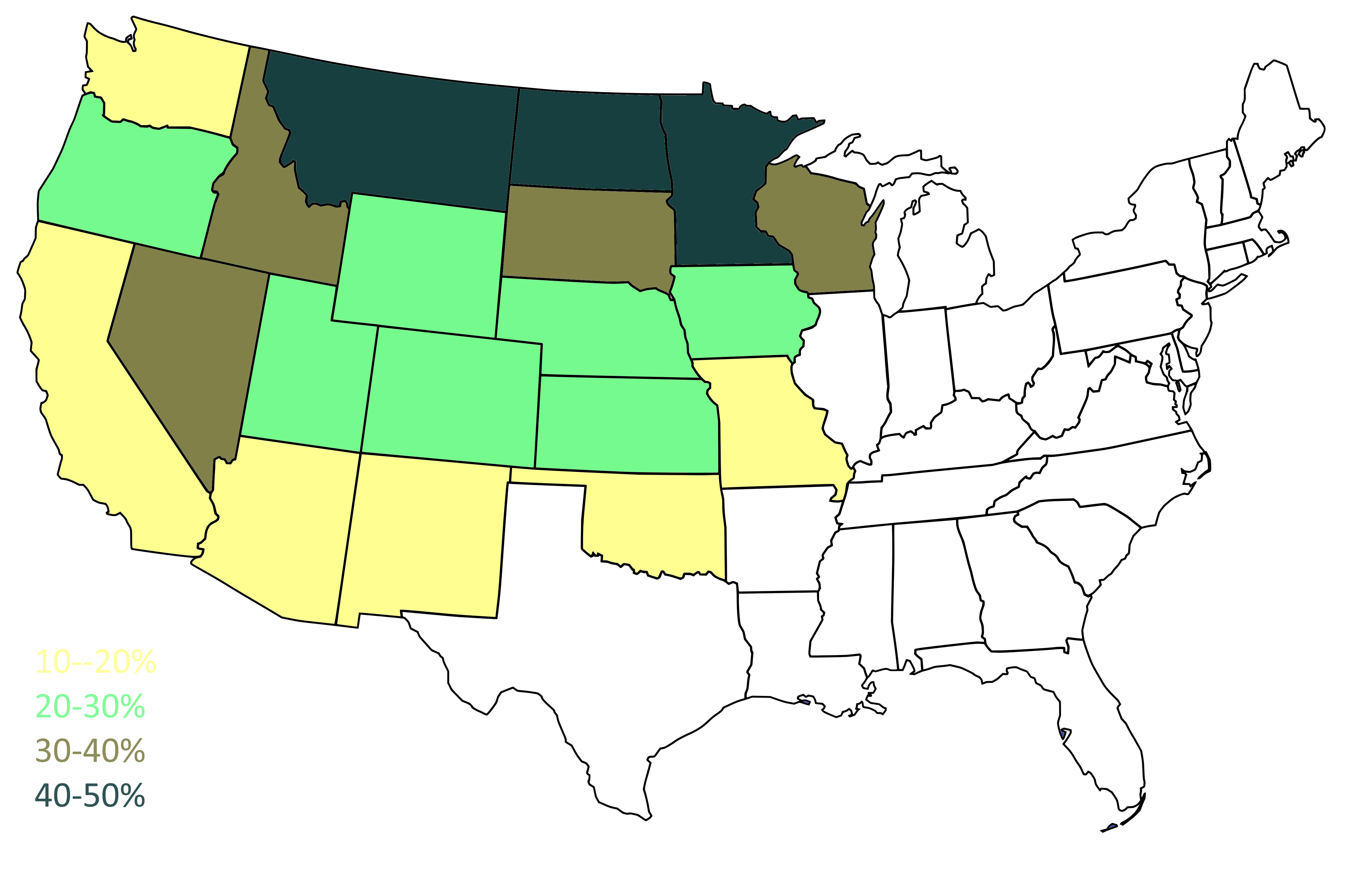

Democratic Party – Garner/Green

Vote Share: 11.33%

Popular Vote: 5,195,188

Electoral Vote: 4

States Carried: 1 (RI)

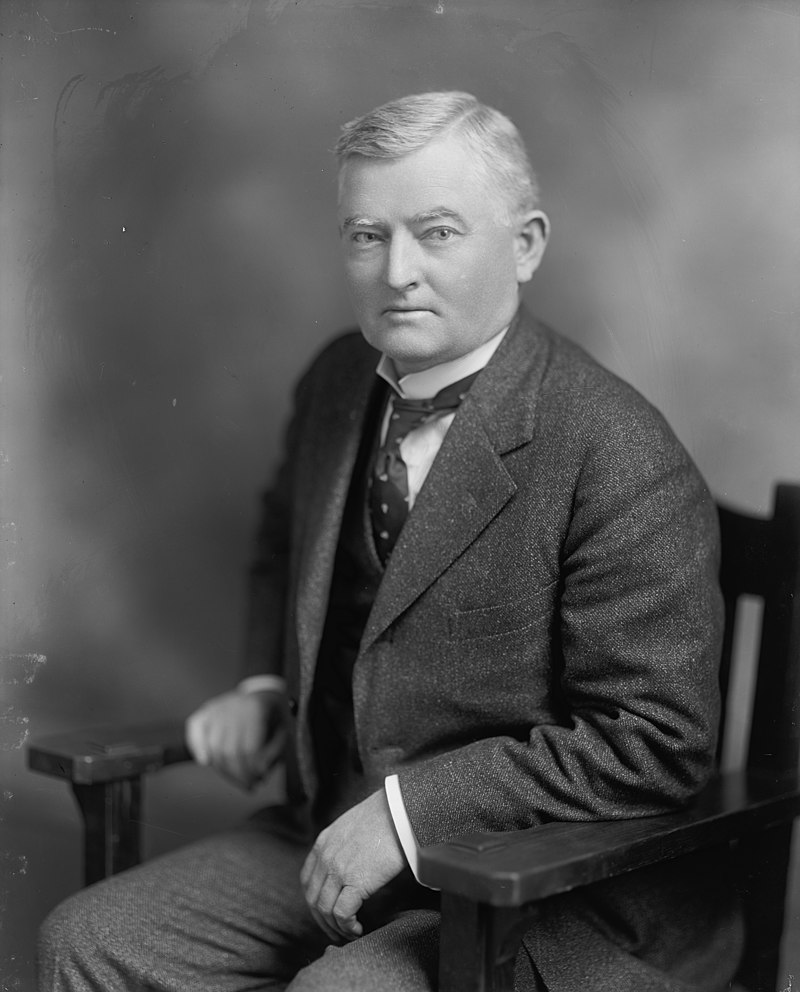

Nance Garner, known as ‘Cactus Jack’ in his native Texas, had entered the electoral cycle expectant that, despite a poor Democrat performance in the 1934 midterms, the unpopular of the outgoing Republican Hoover administration would make him the favourite to come out on top in an unpredictable contest. He could hardly have been more wrong.

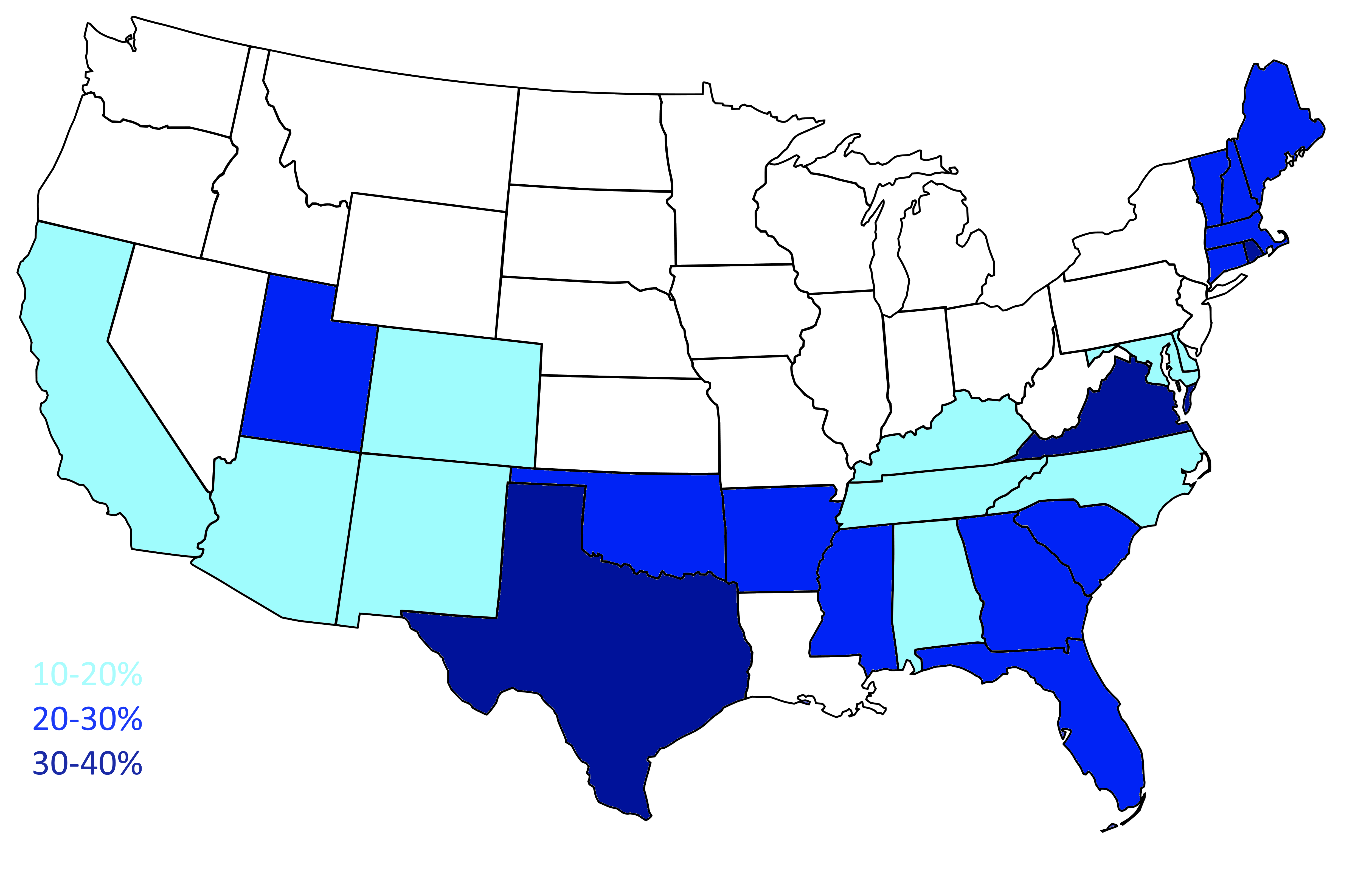

Although placing fourth in the popular vote with a paltry 11%, the Democrats finished a remarkably poor fifth in the electoral college. Indeed, Vice Presidential pick and Governor of Rhode Island secured the party’s only victory as the Democrat ticket won by just over 2,000 votes in his home state. The party only managed over 30% of the vote in two other states – Texas, Garnett’s home state, and Virginia.

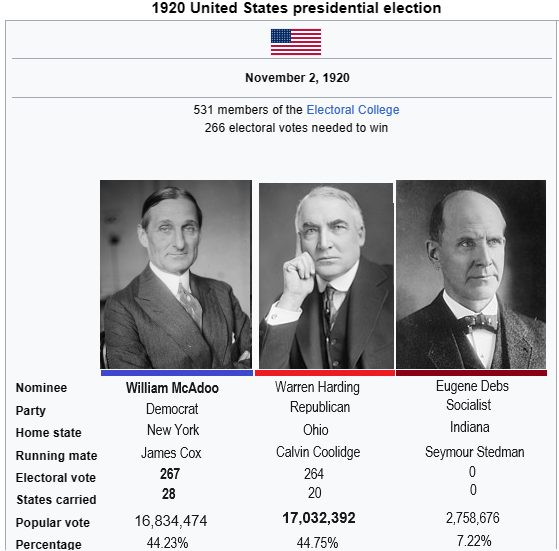

For a party that had held the White House for 16 years between 1912 and 1928 under the Presidencies of Woodrow Wilson and William McAdoo, the fall from grace was stunning. As recently as 1932, the Democrats had been strong enough to run Herbert Hoover to a stalemate in the Presidential election while a strong midterm performance had made it largest party in both Houses of Congress in 1930. Now it survived only as a regionally significant, albeit losing, oppositional force across the South and New England, reduced to fringe party status throughout the rest of the nation.

Of the two traditional parties, the Democrats had been suffered far more intensely from the rise of the radical insurgent parties. In the North, the Socialists had chased the Democrats away from historic bases of support among unionised industrial workers and left-wing intellectuals while in the West, Olson and his Farmer-Labor Party had co-opted the Plains radical tradition for itself. But the greatest threat to the party was none other than one-time favourite son Huey Long and America First, which had not only taken over the majority of the party’s voter base wholesale but also but siphoned off much of its grass roots organisational structure, above all in the South but also right across the nation. What remained was a Bourbon Democrat rump – conservative, elitist and woefully ill-prepared for the militant mass politics of the day.

Farmer-Labor Party / Progressive Party – Olson/La Follette

Vote Share: 8.14%

Popular Vote: 3,733,448

Electoral Vote: 22

States Carried: 4 (MN, MT, ND, NV)

While all five of the major Presidential tickets in the 1936 election had highly regionalised support, none was more so than that of Minnesota Governor Floyd Olson and Wisconsin Senator Robert La Follette Jnr, which ran under the banner of the Farmer-Labor Party or Progressive Party in different states. East of the Mississippi, the ticket struggled to compete for 1 or 2% of the vote alongside other tiny fringe candidates. However, in the West it was the premier force of anti-establishment radicalism – crushing what remained of the Plain and Mountain West Socialist tradition and outcompeting America First among the millions of angry rural voters of the Western half of the Republic. With its greatest strength in the North close to the Canadian border, where it picked up three of its four state-wide victories and fell to narrow losses in South Dakota, Wisconsin and Idaho, it was a competitive in well over a dozen seats.

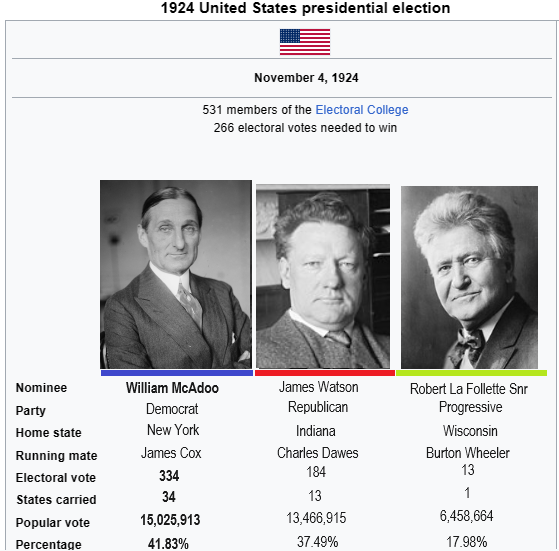

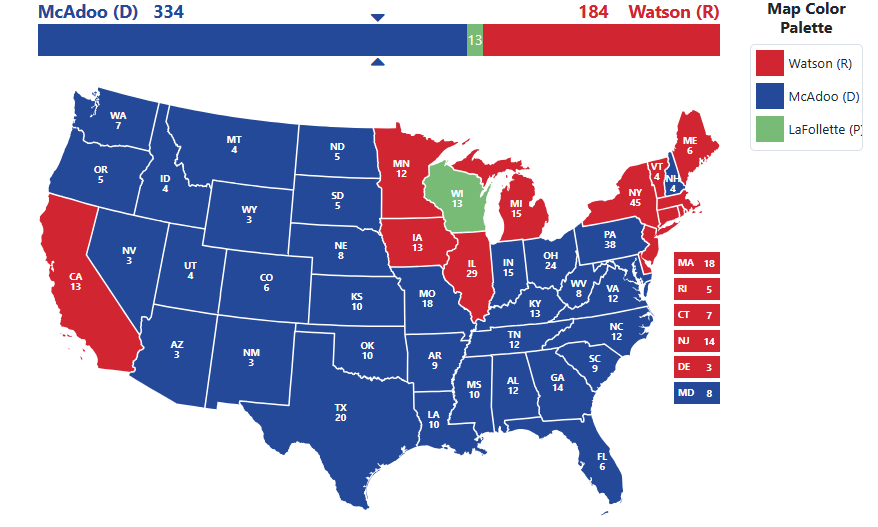

The Olson Presidential candidacy was among the latest to formulate in 1936. Olson tapped into the long tradition of rural Populism, which had flourished as a third party force in the late nineteenth century by channelling the frustrations of homesteading farmer of the American West. In 1892 the Populists had carried five western states, before their movement later rallied behind the movement of the radical Democrat William Jennings Bryan in his three failed Presidential campaigns of 1896, 1900 and 1908. This radical impetus had never truly been extinguished, and revived again for Robert La Follette Snr, the father of Olson’s 1936 running mate, to launch a strong third party campaign in 1924, again winning widespread support in the Plains and Mountain West and winning his home state of Wisconsin.

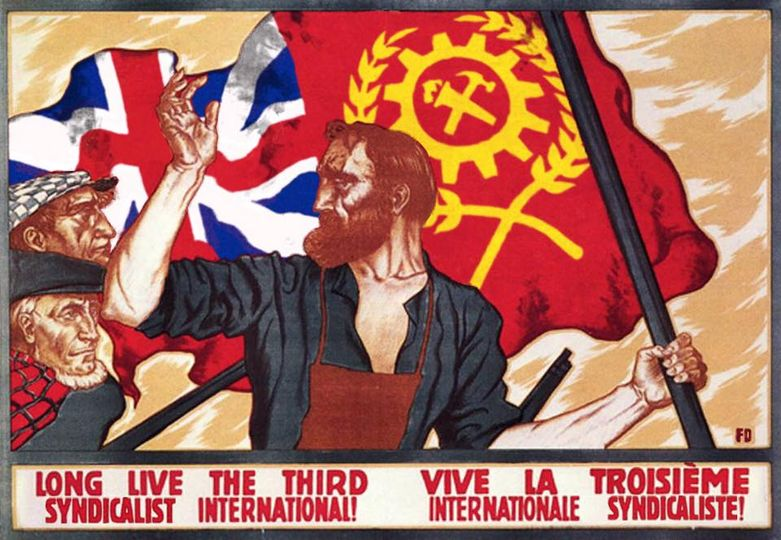

The place of the Populist tradition within American politics grew more strained as the traditional parties broke down and the forces of Syndicalism and Longism grew in strength. While both insurgent movements could claim a share of this tradition, many sought a radical democratic alternative to both the traditional parties and the new extremist movements. In Minnesota the Farmer-Labor Party and in Wisconsin the Progressive Party had functioned as independent entities in their own right for many years by the late 1920s and early 1930s when they came into direct competition with the advancing power of syndicalism. It was in this competition with red tide from the east that they developed a distinct centre-left and progressive philosophy that rejected the bigotry of the Longist, the class war of the syndicalists and the anti-democratic ideology of both.

For a time in the summer of 1936, with the strength of America First and the Socialist Party becoming ever more clear, Olson had been at the forefront of an attempt to negotiate a broad alliance with the Democrats and Republicans that would keep the anti-democratic parties at bay. Despite the failure of this initiative, Olson chose to forge ahead with his own candidacy – setting the Great Plains alight but making little impact in the East.

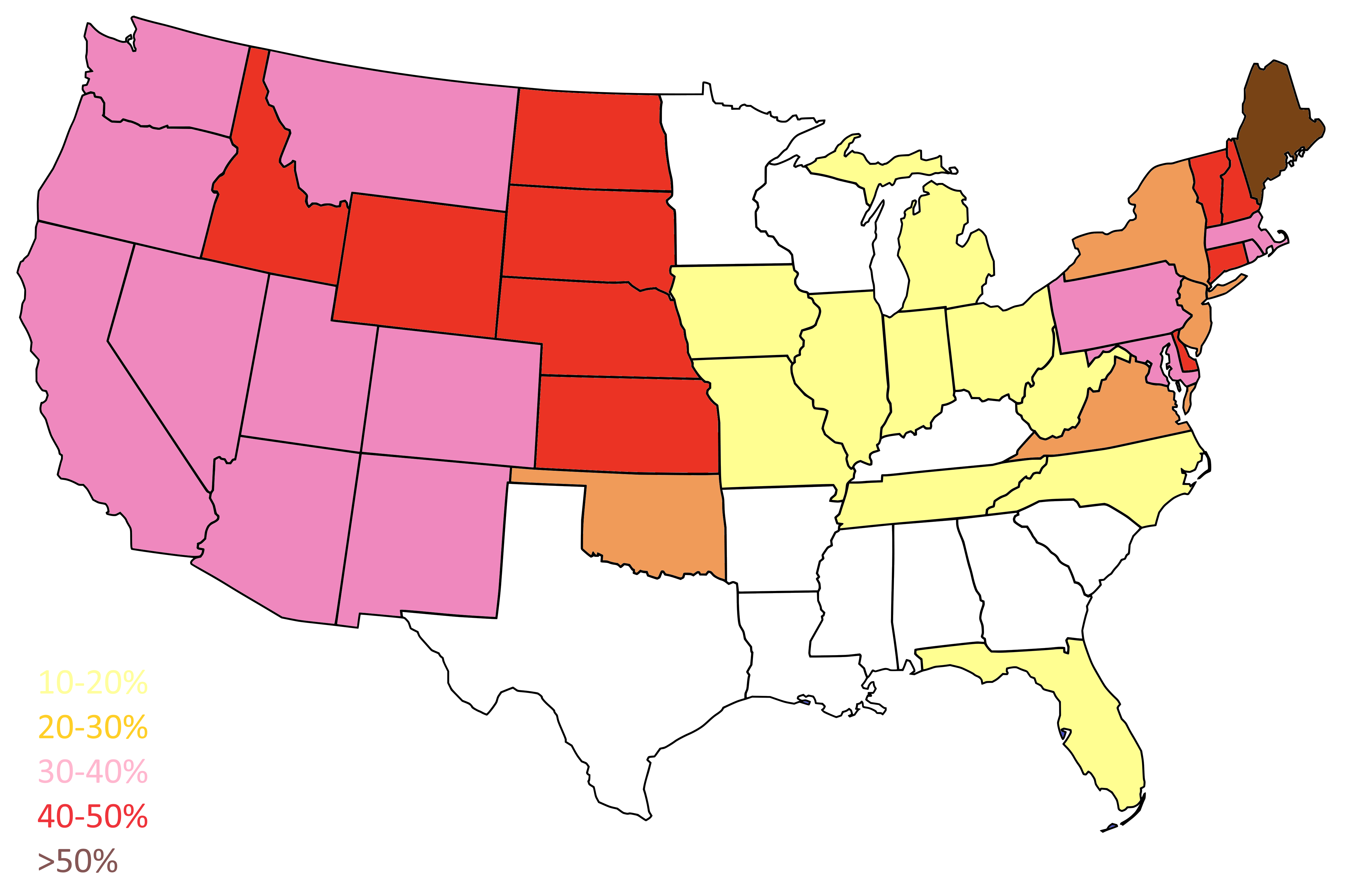

Republican Party – Landon/McNary

Vote Share: 24.15%

Popular Vote: 11,074,235

Electoral Vote: 112

States Carried: 16 (CA, CO, CT, DE, ID, KS, MA, ME, NE, NH, OR, SD, UT, VT, WA, WY)

When he was nominated as the Republican candidate to succeed one of the most unpopular Presidents in American history in Herbert Hoover, Kansas Governor Alf Landon was presented with one of the greatest hospital passes in political history. Although visibly uncomfortable with the fiery heat of an electoral contest of this unprecedented nature, Landon and his running mate, Oregon Senator Charles McNary, performed admirably.

In the West, New England and Mid Atlantic, the Republican ticket remained highly competitive while it retained a degree of residual support in the now-Socialist dominated Mid West and parts of the South, where it had been a fringe force since Reconstruction. Nationally, the Republicans finished within striking distance of the two insurgent parties, despite slumping to less than a quarter of the popular vote, but ultimately fell to third place.

Landon had gone to the country with a fierce defence of the American Dream, business, sound public finances and the democratic institutions of the United States with a message that, despite her troubles, America remained on a proper course. After Howard Taft in 1912, he was the first Republican to fail to finish as either winner or runner up in a Presidential election. Nonetheless, he had proven the continued relevance of liberal democratic ideals to America amid the tumult. Indeed, while the two traditional parties had sunken to unprecedentedly low support, it spoke volumes that their combined vote share was significantly higher than either America First or the Socialist Party had managed.

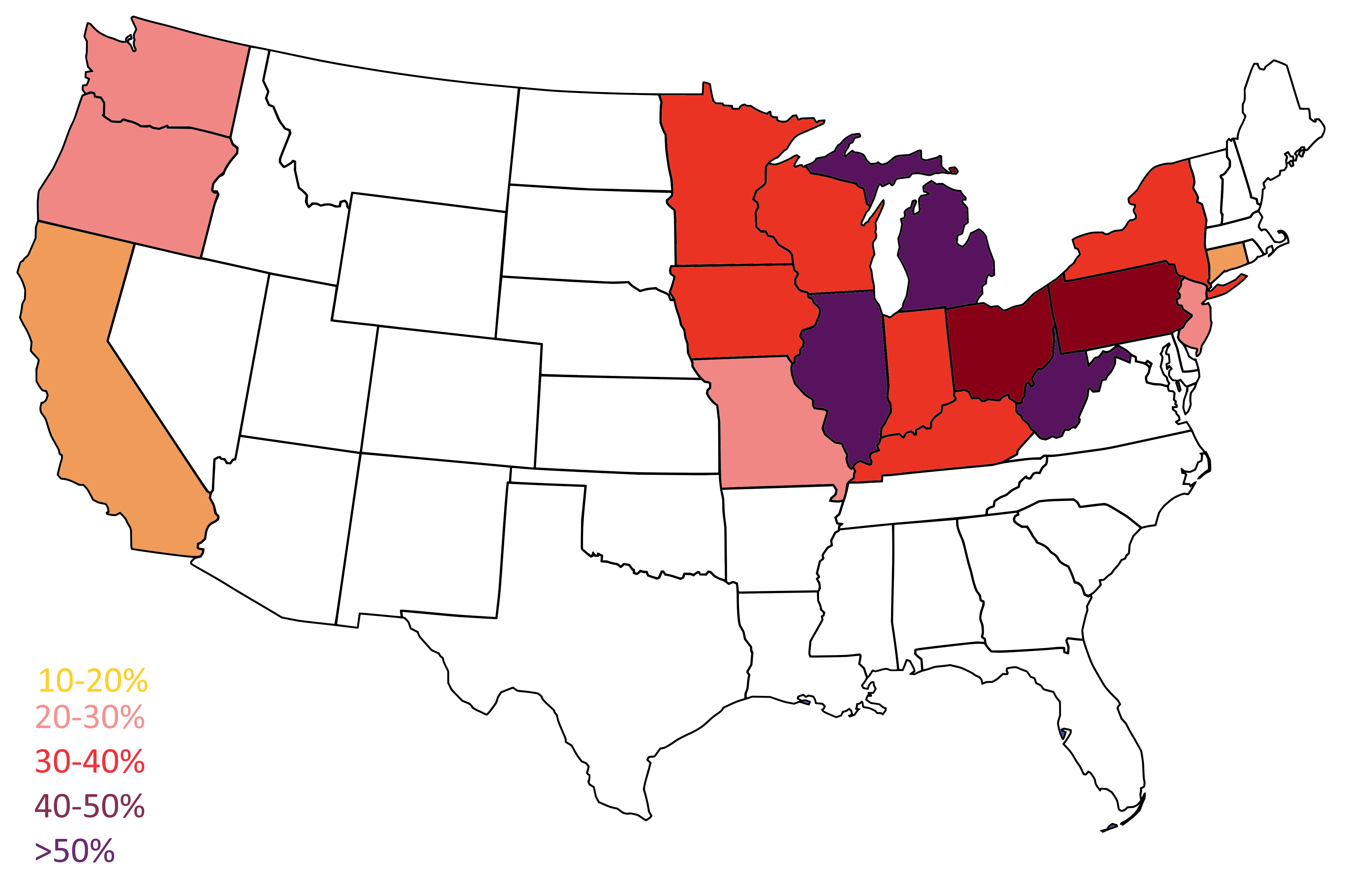

Socialist Party – Reed/Thomas

Vote Share: 28.33%

Popular Vote: 12,990,660

Electoral Vote: 188

States Carried: 8 (IA, IL, MI, NY, OH, PA, WI, WV)

The Socialist Party, the political wing of the Combined Syndicates of America, represented the most complete challenge to the established order of American society with a programme that promised the complete upturning of the institutions, economy and class structure of the United States in line with the revolutionary syndicalist regimes across the Atlantic in Britain, France and Italy. Along the charismatic radicalism of Jack Reed was to balanced by the relative moderation of his Vice Presidential pick Norman Thomas, a formerly the Mayor of New York City and Socialist Presidential nominee, there was little to disguise the magnitude of their political offer.

American socialism had been building towards this moment for at least a quarter of a century. After the pioneering campaigns of five-time Presidential candidate Eugene Debs between 1900 and 1920 had built up a base for socialism in America, the syndicalist movement enjoyed explosive growth from the late 1920s as American capitalism juddered to a halt under the weight of the Depression; the example of the European revolutions brought weight and inspiration to syndicalist ideals; and the American movement itself consolidated and professionalised itself. By 1928 the Socialist Party had elected its first Senator and wielded a strong cohort in the House of Representatives, in 1932 it denied either major party an electoral college victory and through the Presidential election to Congress – resulting in the re-election of Herbert Hoover to the consternation of many.

For a time, and with the American societal crisis intensifying, the onwards march of syndicalism appeared unstoppable and inevitable. However, in the mid-1930s other radical alternatives to the status quo emerged. For all their hatred for one another, the America First movement appealed to very similar emotions as the syndicalists with its appeal to redistribution, a fight against poverty and upturning of the existing order, while the late emergence of Floyd Olson’s Populist candidacy scattered the embers of Plains socialism almost entirely.

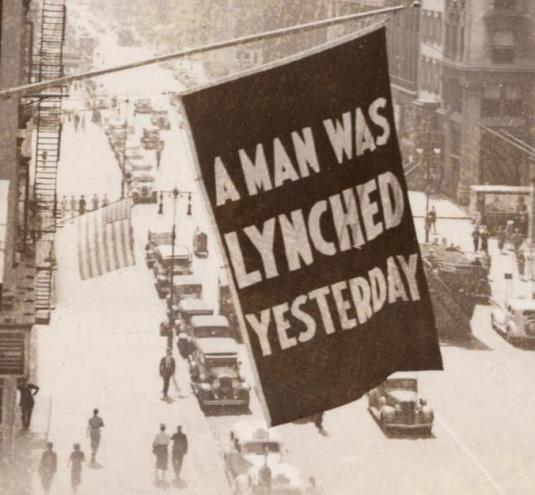

Despite all this, in election day more Americans would cast their ballot for Jack Reed than anyone else with nearly 13 million putting their faith in revolutionary change. Given this, it is remarkable that the Socialists won in just eight states and scored only derisory support across great swathes of the country. Indeed, outside of the industrial cities of the Mid West and Mid Atlantic, the coalfields of Appalachia and a handful of coastal Pacific cities – principally Seattle and Portland – the party had vanishingly little support. Its electorate was tightly focussed on unionised workers, left wing intellectuals and a handful of key ethnic minorities – notably the Jews of New York and Blacks who had migrated to the Northern cities over the preceding decades. Although it won in only eight states, these included the four most populous in the Union as well as the seventh most and the largest part of the nation’s industrial capacity.

Reed fell well short of outright victory, and even finished behind Huey Long in the electoral college, nonetheless with a plurality of the popular vote he held a clear claim to victory. In a wild election party in New York, he would announce himself as the rightful President Elect and called upon his followers to prepare themselves to defend his claimed victory.

America First Party – Long/Lemke

Vote Share: 26.72%

Popular Vote: 12,249,418

Electoral Vote: 205

States Carried: 19 (AL, AR, AZ, FL, GA, IN, KY, LA, MD, MO, MS, NC, NJ, NM, OK, SC, TN, TX, VA)

Huey Long was the single greatest unknown entering into the 1936 Presidential race. His party was young, untested electorally, but extremely militant and belligerent as he promised to bring down the established order in Washington and destroy the spectre of syndicalism.

It had been during his successful term as the Democratic Party Governor and later Senator of Louisiana, during which he had built up an impregnable statewide political machine by fair means and foul and started to articulate his distinctive Share Our Wealth programme. This called for a decisive break with the dour pro-business politics of the Democratic establishment in favour of radical government action, economic redistribution, a response to the acute problems of rural poverty and limits on the accumulation of great fortunes.

These ideas made him the darling of the Democrat base in the early 1930s, but he nonetheless lost out on the party’s 1932 Presidential nomination as deals in smoke-filled backrooms handed it to the conservative Albert Ritchie instead. After the indecisive result of the election that year left it to Congress to decide the winner and the Democrats agreed to grant Hoover a second term in exchange for some political concessions, Long was incensed and left the party in a rage.

It was only ahead of the 1934 midterms that he launched the America First Party, adopting the Share Our Wealth Programme alongside a forthright nationalist policy, and secured scores of victories, chiefly in the Deep South and at the expense of his former party. With proof of concept secured, Long announced his intention to build on this foothold with a run for President, coining his famous slogan “Every Man a King”.

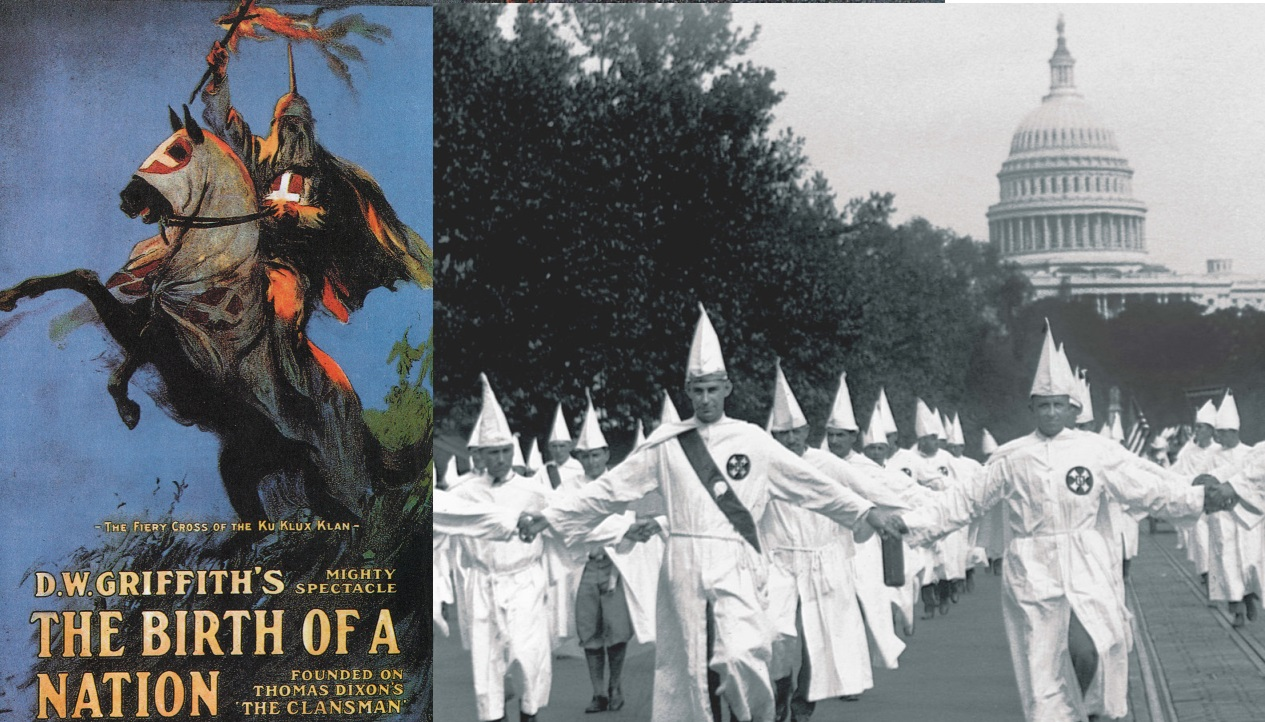

After 1934, America First grew explosively and attracted support from an array of different constituencies. While Long himself liked to focus on his economic programme, nationalism and anti-syndicalism, his movement unleashed forces that he had limited control over. Contradictorily, while the party, particularly in its southern heartland, had a fiercely nativist hostility to Catholicism and immigration in defence of the traditionally Protestant American national character, one of Long’s most prominent allies was the Catholic Priest Father Coughlin whose influential radio show brought the Longist creed to the millions of working class Catholics in the Northern states that had once been central to the Democrat political base. Indeed, in Indiana – in which Long would stun the Socialists by building a winning coalition in 1936 – the America First electorate relied on the organisational prowess of both anti-Catholic Klansmen, who remained influential in the state even as they had declined elsewhere, and anti-socialist Catholic clergymen for its success. Anti-Semitism was also widespread, and a somewhat unifying force, within the movement – with hatred of syndicalism and finance bleeding into ancient prejudices that witnessed the prominence of Jewish figures on Wall Street and among the Combined Syndicates alike and saw a conspiracy against the American race.

Perhaps above all, Long promised to be the strongman who would cut through the corruption and impasse of Washington politics, destroy the syndicalist menace and ensure the continued survival of the United States at a time of existential peril.

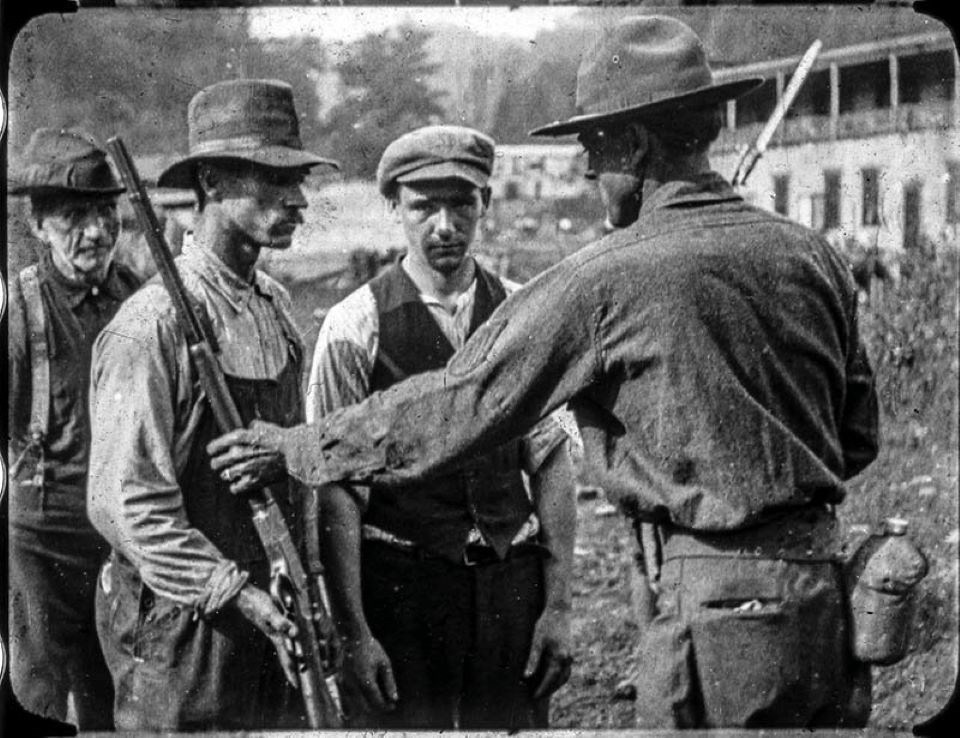

Like the syndicalists, the Longists also retained a large paramilitary wing, the Minutemen, with which they intimidated their rivals, did battle with syndicalists where they found them and sought to project an image of militant vitality and strength.

On election day, remarkably, the America First Party had the only Presidential ticket that won at least 10% of the vote in every single state, leading Long to claim that he led the only truly national party. This support was highly concentrated in the Deep South, where America First secured the lion’s share of the Democratic supermajorities but was also strong across the South West, the Border States and into the Mid Atlantic – with Long notably winning states as far North as Indiana and New Jersey.

Had it not been for poll taxes and other turnout suppression methods keeping voting limited in the South, as had been the case for several decades, Long might well have beaten Reed to the popular vote. Nonetheless, he finished narrowly ahead of his socialist rival in electoral college votes, although well short of a majority in his own right, while losing in the popular vote. Despite this, Long echoed the actions of his main rival by celebrating “the most important victory in the history of the Republic”, and readying his Minutemen to enforce his triumph.

The Aftermath

Despite the victory claims of Reed and Long, the archaic machinery of the American Constitution did not recognise either man as the rightful President. This was an election in which there had not been any winners. With no candidate achieving a majority in the electoral college for the second consecutive electoral cycle, the fate of America would be decided behind closed doors in the Houses of Congress.

According to the arcane of the 12th Amendment to the Constitution, the House of Representatives – hopelessly divided between the parties – was tasked to decide the next President from among the three candidates with the most electoral votes: Long, Reed and Landon. Meanwhile, the Senate, in which the traditional parties remained notably stronger, was to appoint a Vice President from the two candidates with the highest number of electoral votes: namely William Lemke and Norman Thomas. It was not out of the question, legally speaking, that Congress might select candidates from separate tickets.

This was a recipe for total hysteria and chaos. With both Long and Reed claiming victory while sharpening their swords with the American establishment looking on in paralysed horror, within six months the United States would be consumed by the flames of the most bitter and destructive conflict in its history – the Second American Civil War.

This history tells the story of how the greatest nation on earth reached this point of ultimate despair, the consequences of the election and the carnage of the civil war that followed as America forged a path forward amid a world tumbling into darkness.