In the name of Allah, the Compassionate, the All-Merciful, I tell my tale. For there is no god but Allah; and Mohammad is His prophet.

Know, O Sultan, that my father was a merchant of Venice, as was his father before him; and that although their house was not the oldest, nor the wealthiest, nor the greatest as men count greatness in that city of merchants, still it had great honour among them. For though the Gangrel name is not to be mentioned with the Dandolo or the Aiello, whose fame may have penetrated even to these distant shores, my great-grandfather Gnupa served, for some years, as Doge. And although he had won that title by force of arms, when he felt the end of his long life nearing, he did not pass the rulership to his son, as almost any other man would have done: For he said he had taken the city for a purpose, and had accomplished that purpose, and would prove his good faith by not extending the power he had stolen, once the reasons for the theft were gone. For this reason he abdicated the Dogeship, and restored the elections and the Council of Ten as they had been in his youth, with but this one exception: He made it law that Venice should never lay any levy or tariff on ships bringing goods into their harbour, except for what should be needed to maintain the docks and the lighthouses. And in particular, that no Doge of Venice, be his thirst for glory ever so great, should have power to lay taxes for any foreign war; “let the Doge live off his own”, he said, and the great houses agreed to his rule, and wrote it into their books of law. For in his youth, Gnupa had been forced to pay the Doge’s Penny to pay for a Crusade, for a war he had no part in and a quarrel that was none of his own; and so angry was he over that theft, that he devoted his life to ensuring it should never happen again - at least in Venice, the city of merchants that he had made his own, and loved more dearly perhaps than any man born there.

For his decision and his law, Gnupa was given great honour among the merchants of Venice, and the house of the Gangrels was welcomed among the gentilhuomo, the great men who form its nobility and elect the Doge from among their number. For they saw that his words about the Doge’s Penny were not merely an excuse for a power-hungry adventurer, but the true cause of his drive for power; and moreover that the power he won had not corrupted him, and when he had accomplished his purpose, he laid it down and allowed others to take it up for their own purposes; and his sons and grandsons became merchants and citizens, wealthy and powerful indeed, but not claiming any special privilege over others. This, they said, was the honor of a merchant, who does not seek to enrich himself by force or threat, but only by giving others value for value received. And when Gnupa’s son became the head of his house, he took those words for the new motto of the house of Gangrel: Value for value received.

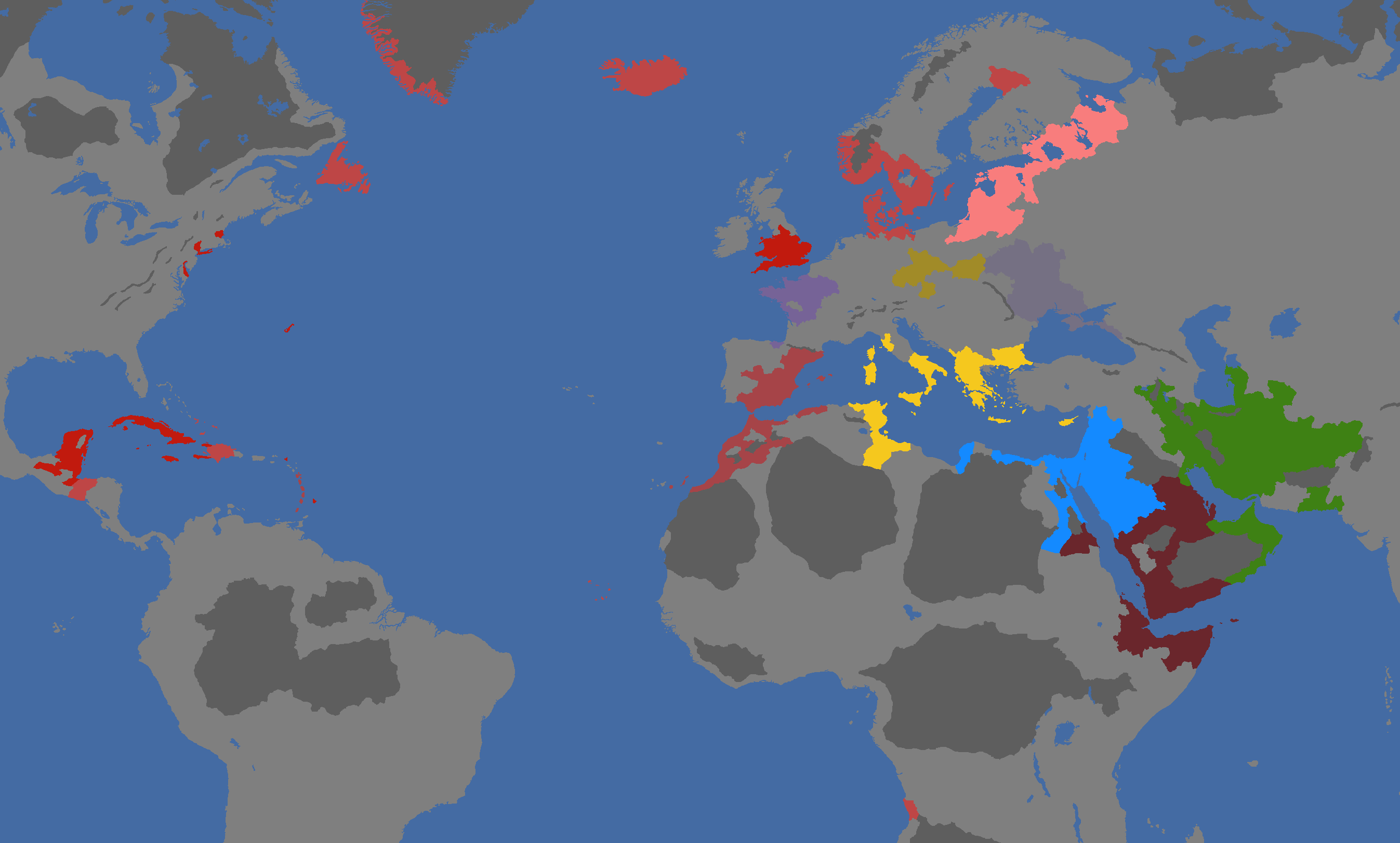

Alas! Allah appoints our rising, and our going down; and all things are accomplished by the will of Allah. In my father’s and my grandfather’s day, Venice prospered, and as the city rose so did the house of Gangrel. Our ships carried goods from Iceland to Alexandria, from ancient Colchis to the shores of Tripoli; grain, silk, furs, glass, rare perfumes, amber, pearls… name the good, and I will tell you the Gangrel bottom it was carried in, or that of our competitors and colleagues. For in fair trade there is no lasting enmity, and the man who loses this year’s contract will return more cheaply the next, and smile at his vengeance that harms none. But that is the honor and glory of merchants; and in the affairs of princes… it is sometimes otherwise.

The rise of Venice, though it harmed none, made jealous those who believe that nobody rises except through another’s fall - which is to say, almost every man, save those who have built great wealth by doing nothing save exchange one thing for another, and give value for value received. Our enemies conspired against us, and stole blood and treasure from their subjects to build ships of war, and hired thugs not to protect their own lands against bandits and pirates (as any man may rightfully do) but instead to turn bandit themselves, and fall upon Venice in numbers beyond what the city could withstand.

We Gangrels are loyal to our salt, and we love our city; when it came under siege, we fought. Venice has no great fortifications to hold off an enemy; its walls are the sea itself, and the ships that travel the waves, and for many months Gangrel ships were the very foundations of those walls. And yet there is only one end to a siege, if no relieving army will come; and the Doge’s messages to our allies, and to all the princes of Europe who had been glad enough to buy our goods (at excellent prices, I may add) in peacetime, went unanswered. For it is only among merchants that it is honor to give value for value received; and the prophet Isa spoke wisely when he said, “put not your trust in princes”.

Seeing the end must come, we gathered our ships, such as were fit to travel the ocean, and we laid in guns and stores for a long journey; and we awaited the northern wind that carried our ancestor south from far Iceland. And when it came, we sailed; for you may know, O Sultan, that the name of our house, 'Gangrel’, means in the Norse tongue - not that spoken in Venice - ‘Wanderer’.

I will not tell the tale of that wandering today, for I see impatient glances among your court, and well I know that the time of Sultans is not unlimited - not even for stories of battle and adventure well worth the hearing, which I will gladly recount on another day. I shall omit entirely the epic of how we ran the Tyrian blockade - of the long stern chase down the Adriatic, and how we tweaked the tyrant’s nose when we docked in Salerno under a false flag - of our longshore raid in the Peloponnese, where we filled our barrels with water and our holds with Greek silver - of our landing in Alexandria, and how we sold our ships for camels and fled south, into the desert. I shall not relate our dealings with the Jews, or the manner in which we took advantage of their greed; nor how we bargained with the Arab tribes for safe passage; all these stories must belong to another day. No, I shall go straight to the point, as befits an honest merchant, and speak my petition plainly, as I am a man of few words, and those few, straightforward and simple.

O Sultan, I ask that you grant leave to settle myself and my house in your lands, and permission to trade freely in the surrounding waters; and to ease your concern in doing so, each man of my household has publicly proclaimed the Shahada in front of many witnesses, or if he could not in good faith do so he was released from my service with a purse of silver and my good wishes. For I have taken to heart the story of Gnupa’s paying of the Doge’s Penny, and a lesson therefrom which is different from his: He sought to prevent the state from levying taxes for a quarrel that was none of his own. But I, standing on his shoulders and seeing farther, wish instead to take up that quarrel, and to join the side of it that has never bothered me and mine, but dealt fairly and honorably with us: For it is known that the Prophet himself, praise be upon him, was a merchant of Mecca, and that his successors have always favored trade and those who deal without violence. Therefore, O Sultan, I ask also for a place in your court, to become your advisor in dealing with affairs of the north and of the Christians; for having lived among them all my life, I know much of their ways. And I know, too, that this Ocean, which they call the Indian, must soon deal with their guns, their seafaring ships, their joint-stock companies… and their greed.

This, O Sultan, is my petition; and by this means I hope to protect my house, and these lands which I wish to adopt with all the fervour wherewith we loved Venice, and the freedom of men to give value for value received, into the far future.

But Allah, alone, knows all.