BASILEUS BASILEON:

Chapter I

Strategos Leon Phokas

This work is a history of the Phokas dynasty, the family that ruled the Roman Empire for […]. Their origins are unknown, although propaganda lavishly claims that they descend from the classic Flavians, and some Arab historians claim they originate from Tarsos. The likeliest origin is from Armenian immigrants, we don’t know if from nobility or lower classes, but they did grow as rich landowners in Kappadokia after settling there. Service in the themes followed naturally, and by the late 9th century they rose to the very top of the anatolian military class.

But first, we must put everything into context. In the 860’s, Romania was rapidly changing. For over 200 years, the Romans had only parried the attacks of the caliphs, suffering raids every year, on occasion taking the offensive. But the once mighty Abbasids were decaying. Their last hurrah was the sack of Amorium, 30 years before Basileios the Macedonian’s rise. Now they were prisoners in their capital, dominated by court intrigue and all-mighty generals.

As Arab power waned, Constantinople began spreading it’s influence once again. Great generals from Anatolia rose to prominence, leading Rome to a glorious era of expansion and success. The protagonists of this resurgence are the Phokas.

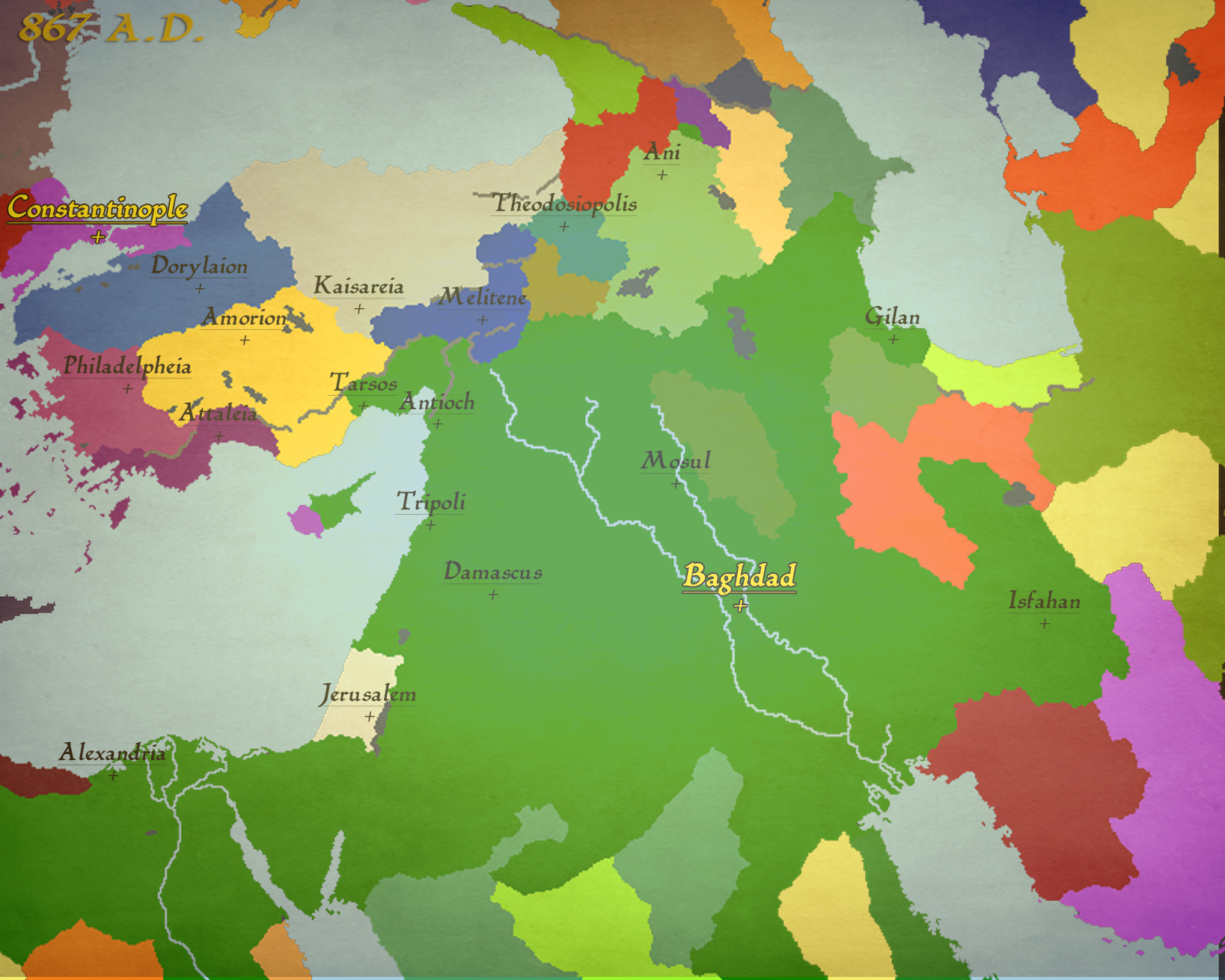

Map of the Mediterranean world in the wake of Basil the Macedonian’s Ascension

Much ink has been used to talk about them, and with good reason. It has come to my attention that a full narrative history of this period hasn’t really been published for the last 50 years, with Manuel Krinites’

The Roman Resurgence (717-1132) dominating the discourse among historians for a long time. But recent discoveries from many fields, and a new understanding of our ancient sources has led to more coherent theories and perspectives on late Roman, or Byzantine history. My objective is to revise the traditional narrative making use of this new trends, disposing of old myths and beliefs. As its focal point, we will be exploring the lives of every successive patriarch of the Phokas clan in detail, while of course trying not to neglect those around them. ¿Why not focus on the Macedonians first?, many will ask, and to this I will answer that while important, the trajectory of Basil’s dynasty can easily be tracked while emphazising the more relevant Phokas.

Map of the Middle East, highlighting the key cities in the region, barring Aleppo.

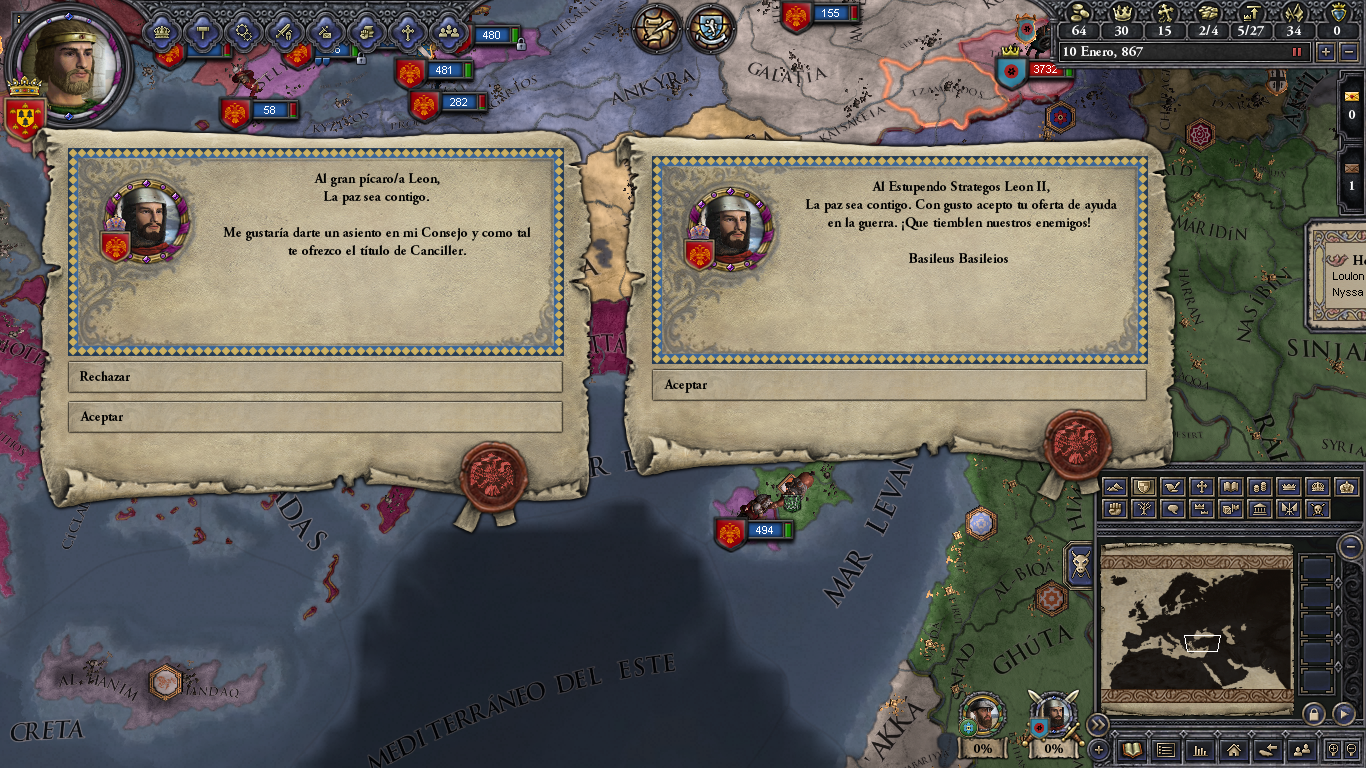

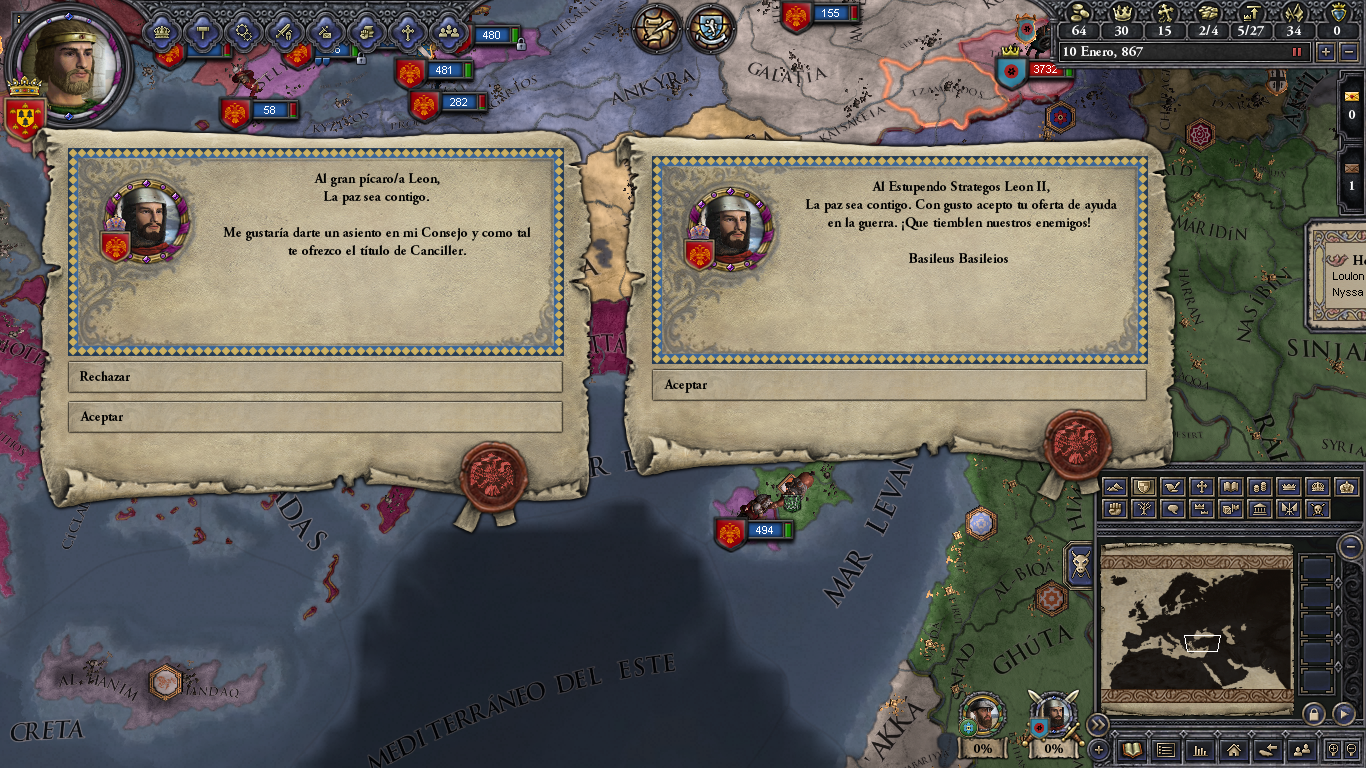

Their first noteworthy member, and the beginning of this history is Leo Phocas (Leon Phokas). He became strategos of the Anatolikon (The Army of the East), one of the four themes in Anatolia and the one defending the Taurus mountains, sometime in the early 860s. With Basileios the Macedonian’s rise, he was named Logothetes tou Dromou, charged with diplomats as well as some parts of court ceremony. He was, definitely, not fit for the job: Leon was a soldier, and it is recorded that he fought in several campaigns while being a logothete.

In Theodosius’ History he was only given this office to buy his loyalty (along with some bribes) as Basileios settled into power, mostly staying in Loulon (one of the headquarters of the Anatolikon) and campaigning in the East. Leon’s life is full of contradictions between historians, shrouded in propaganda and the attempts to make sense of the man by later historians. Some say he campaigned with Basileios in the Paulician War of 867, others that he was actually in Italy to ensure the loyalty of the governor to Basileios. Theodosius’ account is generally the more reliable one, with him simply being in Constantinople and sending an embassy, not himself, and some detachments of the Anatolikon to reinforce the campaign in Armenia.

No matter whatever involvement he did or did not, the Romans crushed the Paulicians. Basileios defeated them near Sebasteia, and captured Tephrike, although not having the time or resources to hold it, he opted to take tribute in return for leaving. Besides, the empire had a much more important foe to take care of: the Aghlabids of Africa. For decades they had slowly eroded Roman control of Sicily, and now they were trying to finally push them out. But Basileios could not allow it. A small expedition sailed to the island, reinforcing the local troops and turning the war into a stalemate. The Aghlabids responded with a daring fleet of their own.

The Emir himself sailed through the Mediterranean first to the Arab pirate haven of Crete, and then plunged through the Aegean, pillaging several small islands and finally landing in the European side of the Dardanelles. Basileios rushed from Armenia to defend the capital. The Muslims only managed to sack the countryside of Kallipolis before meeting the emperor. The two armies clashed, and although the Arabs fought hard, Basileios’s numbers decided the engagement. Still, the Emir managed to make it back to their ships with a large party, and crossed the strait to Anatolia, about 1500 soldiers. Basileios deemed them an insignificant threat, commanding his strategoi with the task of hunting them down.

But they were too fast for the Opsikion, reaching Caesarea in a matter of weeks, putting the city under siege. As Basileios had defeated the paulicians, Leon felt free to focus his armies on Cilicia, so the Anatolikon wasn’t home when the Aghlabid forces marched into Anatolia. He had ordered his commander Theognostos to cross the Gates and raid the surroundings of Tarsus, while evading conflict. The commander gathered the regiments of the Anatolikon, the first of the Empire, the first Themata. The Arabs said that it fielded 15.000 men, guarding it were 34 fortresses. Theognostos could only muster some 1800. The army prayed to St. George and marched to the Caliphate.

They met no initial resistance, the small garrisons quickly withdrawing to their fortresses. Theognostos laid siege to Lampron, which guarded the city of Tarsus. This was an important port, and one of the main bases of the Jihad. Jihadi warriors gathered in these cities, and every year marched into the House of War, to sack the infidel for glory and fortune. The Roman Empire was unfortunate to be the House of War. But now, the byzantines were counterattacking more than ever. For two centuries they laid low, carefully harassing the Arabs as their people were massacred, only allowing themselves to strike at the right moment, like a scorpion to a slow and distracted foe. In the times of Basileios this had changed. Only small armies from emirs crossed the mountains in those years. And now Leon was sacking them.

Lampron held out for several months, but Theogonostos knew better than to rush into an assault. He had secure supply lines back to Seleucia, and through the Gates to Loulon. A small fleet sailed to the gulf of Alexandretta to remain alert of incoming Arab armies. While they settled for a small siege for the rest of 870, the army took the pleasure of thoroughly stripping all of the land outside the walls in the region. These were probably christian dominated areas, since Arab-muslims normally concentrated in the cities. But this was just the nature of warfare, the moral implications of pillaging fellow christians not really being a concern for the pragmatic Romans. They were in enemy territory. The fortress ran out of supplies and surrendered.

Victorious, the army marched home through the Gates, as the snow was setting in, making it just in time for the New Year. Great celebration was held in Tyana, as the loot was sold in the markets. The basileus, the strategos and the army receiving the spoils. In that order. But, as they were preparing to disband and make it home before the winter got too harsh a messenger arrived from Caesarea. He begged for the Anatolikon come to their aid: the city was about to fall to the Aghlabid army. Normally, an army this size would have been a mere nuisance. Problem was; the Armeniakon was out in campaign in the Eastern mountains against the Paulicians. So Leon agreed*, but his army needed some recovering, for now, they were outnumbered by the Arabs. They waited for the spring to come, and marched up north to crush the enemy. Theognostos once again leading the army. Too late.

The Anatolikon rolled up to a desolate city, only some stragglers. The tourmarch Gregoras exploded in anger, swearing that the Arabs would soon be paint on the hills of the plateau. Theognostos silently agreed, and they pursued the trail left by the raiders. They catched them on Malakopeia, weighed down by all the loot. Some sources claim that the Aghlabid Emir himself was there, leading the army. I find this very hard to believe, but several sources do mention this. This sort of attacks was what the Romans had specialized in for centuries. Using the terrain to their advantage, their enemy being burdened from the loot and drunk with victory.

The pass was somewhat flat, but with large hills on the sides. Theognostos took the infantry, leaving Gregoras in command of the cataphracts, hiding behind the hills on the left flank. The Anatolikon engaged the rear of the Arab force, inflicting some casualties before the Arabs managed to form properly. The two armies struggled, with no clear victor in sight. Then the trap was sprung: Gregoras pounced from the hills, smashing his cataphracts into the Arab right flank, causing a rout and eventually, the collapse of the Arab army.

The vanquished Arabs left behind their camp: with all the prisoners and loot. They were freed, their property returned (saving a small cut for the soldiers) and escorted back to Caesarea. Theognostos marched back to Cappadocia, and disbanded his army, which was long overdue after almost a year and a half in campaign.

With the prestige of this victory, Leon arranged a marriage between his son Nikephoros and Chrysanthe Argyros, daughter of Leon Argyros, one of the most powerful landowners in Anatolia; his family’s influence spread all over Eastern Pontus. This came with an alliance between the two houses. A couple years prior, he engaged his eldest daughter Kale to the heir of the strategos of the Armeniakon himself: Ioannes Kourkouas, the Lionheart. This general was the leader of the Roman reconquest in the 9th century, under the auspices of Basileios’s capable rule.

Tragically, his daughter died, just as she grew into a woman, the marriage never took place. Leon was devastated by the loss, returning to Tyana to be with his family. After a couple months, he reformed the alliance, by offering the hand of his younger daughter Athanasia to Ioannes’s heir (Romanos). With the alliance now reinvigorated, Ioannes asked that the Anatolikon aid him against the Paulicians. If Ioannes succeeded, they would, finally, be crushed and Tephrike annexed into the Empire. The emperor was preoccupied with a much grander mission: the reconquest of Crete.

But Ioannes was a proud man, he only asked for help after suffering a terrible defeat near Koloneia. The paulicians cornered them and slaughtered two-thirds of the Armeniakon. The Anatolikon was busy with a minor raid in the central part of the Taurus range, Lykandos. The strategos himself took command of the army as it crossed back into Roman territory, and joined with Ioannes in Sebasteia. The two came up with a plan. The Armeniakon army would move to Koloneia, to lure out the Paulicians from their safe capital. Once they left, Leon led his men to Tephrike.

Ioannes had no issue outrunning the Paulicians and reunited with Leon at Tephrike. The paulicians rushed back to their capital, but the Romans had prepared. The paulician army outnumbered the themes, so the strategoi waited in the south banks of the river (a tributary of the Euphrates), with mountains to their right and left. There were no brilliant tactics that day. As the paulicians tried to ford the river they were mowed down by arrows, and the ones who made the crossing met their end at the tip of an orthodox spear. From the 4000 thousand strong army, only 500 managed to escape.

Both strategoi sieged the fortress of Tephrike for 2 months, until the garrison could hold no more. Ioannes occupied it and the army feasted for the great campaign. Kourkouas remained to capture the weaker cities in the region, while Leon marched North to crush the remaining paulicians, hidden in the Pontic mountains. The Anatolikon dealt with them swiftly and returned to their headquarters. By August, 872 Ioannes had fully submitted Tephrike to Roman rule. The campaign was a success, with parties in Tyana and Amaseia ensuing. From this point forward, we know for sure Leon stayed for good in Cappadocia, resigning as logothete ton dromou. Honorable man that he was, after botching an embassy to an important governor he could no longer remain in office with a straight face, resigning upon his return to Constantinople. Basileios accepted, fully knowing this was for the best and that Leon’s loyalty didn’t depend on a court position. Besides, he had reconquered Crete just a few months earlier, his grip on the throne was firm.

Finally free to pursue his real ambitions, Leon began to cultivate himself as a general, reading of Alexander’s campaigns and Sun Tzu’s The Art of War, a gift from an Arab merchant captured in a raid. With his fixture in Loulon, came a more watchful eye on the local governors and dynatoi, which did not sit well at all. Leon began planning annual campaigns against the Arabs, joining forces with Ioannes Kourkouas to destroy the Emirate of Melitene, securing Northeastern Anatolia once and for all. This meant constant taxation, and recruitment of men.

Another factor was that the power of the Phokas was centered in Eastern Cappadocia, while the Western regions were completely dominated by other families like the Krateroi and Melissenoi. So, in the spring of 873 the governor of Amorium, former capital of the theme rose in rebellion, wishing to take the seat of strategos. He expected the other dynatoi to join him, but Leon had wisely spread out bribes and offices around to secure their loyalty. He defeated the rebel near the town of Nyssa, moved west and put Amorium under siege.

After a couple of months, the garrison surrendered, handing over the wife and daughter of the governor. His army trashed, capital occupied and family held hostage, he surrendered to Leon in Christmas, 873. Feeling that an execution on the day would be sinful, he settled on sending the governor to a monastery, seizing his property and keeping his family captive in Loulon. This acquisition greatly solidified Phokas control of the theme. This would be the launching pad of the dynasty and armies that conquered beyond what Trajan himself had dared to. Leon expanded his personal “retinue” of cataphracts, now a private army of highly disciplined and equipped shock troops. These two regiments were the “Kataigídes” and “Lýkoi”, the seed that would one day grow to be the legendary Athanatoi. The harsh life of Cappadocia bred generations of mighty warriors, formed by centuries of Arab raids.

With this successful campaign, Leon welcomed the new year with the birth of his third daughter: Thaumaste birthed a frail baby named Theodosia. Her survival was very much in question but Father Epiphanios, the family’s personal physician managed to save her. Our sources have no other knowledge of 874, but by 875 Leon’s plans came to fruition.

The Armeniakon, heavily reinforced by Chaldian troops invaded the emirate of Melitene from the North, targeting the Marwanid fortresses North of the Euphrates. The Anatolikon in turn attacked from the West, wishing to capture the region of Lykandos, securing another pass into Cilicia. If both operations were successful, Melitene would be completely choked, beset on almost all sides by Byzantine garrisons. Ioannes Kourkouas easily defeated Abdallah al-Marwani’s army (the emir) near Koloneia, the chaldians led by Leon Argyros split off to capture the Keltzene. The Armeniakon pushed south, capturing many towns and laying siege to Melitene itself, if unsuccessfully.

Leon Phokas had no trouble taking Lykandos, capturing the fortress and several cities in a few months. The retreating Arabs, reinforced by jihadists from the Caliphate attempted a counterraid, crossing through the Anatolikon to attack Caesarea. He intercepted them in the city of Rhodandos, less than 200 Romans died, to over a thousand Arab casualties, sadly we have no detailed accounts of the battle. With no real threat left, the army occupied the rest of Lykandos. The emir had no choice but to accept reality: he officially ceded the region to Leon. He gathered in Caesarea with Ioannes Kourkouas for a great celebration. The emperor sent gifts to both strategoi for their great victory.

Depiction of the campaigns of 875

Now, the city of Melitene, one of the jihad's major centres was fully isolated. It had simply too strong of a position to be merely sieged and assaulted, this campaign had cut off it’s supply hubs West and North, so any general would only need to block one way and let the city starve. Capturing Melitene would mean permanently blocking access to Anatolia from the center, while paving the way for Roman forays into Mesopotamia and Armenia.

Triumphant, Leon returned to Loulon and his family. He rested, and arranged a betrothal for his daughter Theodosia to Kallistos Melissenos, an influential landowner inside the theme, further securing the Phokas position. For the rest of the year he trained his troops, and played some war-games with his future son-in-law Kallistos, hoping to create a bond between them. He also promoted the works of his physician Epiphanios, but the produced publication was mediocre, and has not been preserved to this day.

Peace would be short lived for the strategos. In 877, the former emir, now strategos of Crete revolted against Basileios, the themes of Strymon, Epirus and Serbia joined, but they were simply no match for the emperor. Still, this rebellion sent ripples through the Empire. Kallistos Melissenos, thought that if the emperor’s position was shaky, his ally Leon would be weaker. He betrayed the strategos, demanding he give up his position to him. Leon didn’t think twice and rallied his men. The whole of the Anatolikon remained by his side, barring the western regions of Phrygia and Pisidia, the Melissenos heartland.

In spite of the great support Leon had from his officers, his army was still recovering from the campaign against the Marwanids, so Kallistos’ army had similar numbers. It wouldn’t be an easy war. But Leon’s character and reputation proved decisive: hundreds of veterans flocked to Loulon to assist their former general, and, more importantly Ioannes Kourkouas rushed to the aid of his battle brother. Together, they outnumbered Kallistos two-to-one. Leon managed to bait the rebel into attacking near Amorium, thinking the numbers were the same. To his surprise, as the battle began, 3000 fresh Armeniakon soldiers emerged from the North. It was a slaughter. His army annihilated, Kallistos fled into the rugged Phrygia, hiding from the vindictive Leon.

For the rest of the year the strategos hunted him down, occupying all of the Melissenoi’s land. By spring 878, Kallistos laid in chains, his rebellion a catastrophic failure. Leon seized all lands from him, barring a small holding in Pisidia and blinded the traitor. Now the Phokas controlled almost all of the theme somewhat directly. His son Nikephoros received Amorium and Phrygia to govern.

Unfortunately, the story of Leon Phokas ends in this high note. There’s a gap in our sources from 878 to 885. By then, Leon was dead and his son Nikephoros was the new strategos. We know he probably died in the early 880’s, later scholars say 881, some 883. We simply do not know.

Leon Phokas wasn’t a brilliant man. But he was the right one, at the right time. His martial qualities laid the foundations for what may be Rome’s greatest dynasty and the armies that would meet no match for centuries. He and his successors turned Cappadocia into an engine of war, that launched the family and the Empire into the stars. Next, comes his son Nikephoros Phokas, known as the Brute, as well as the Wicked. A more interesting character than his straight-forward, honorable predecessor.