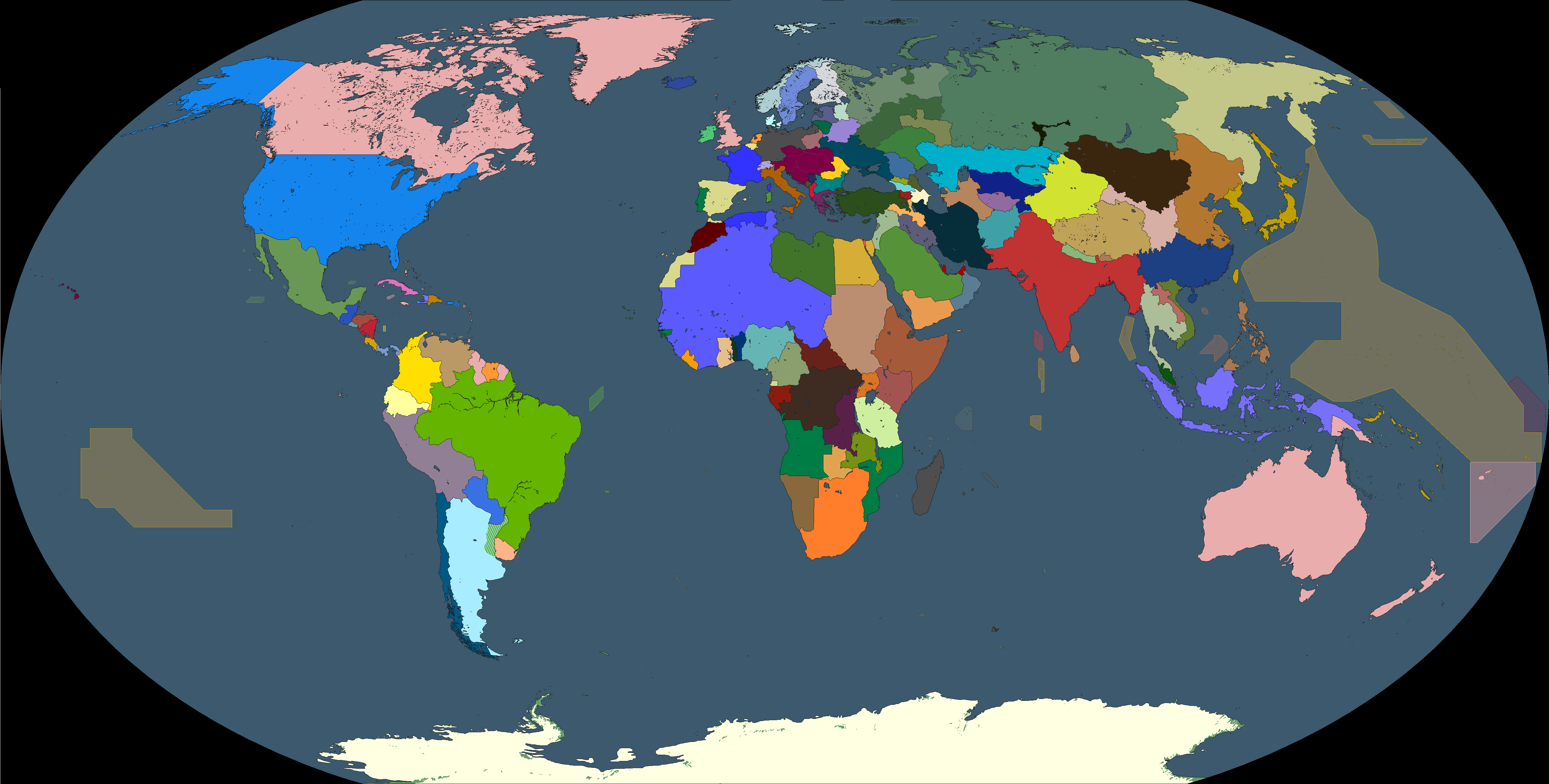

Introduction: The World of 1948

"Germany's strength is forged not by slogans or fanaticism, but by the quiet resolve of disciplined minds and steady hands. A nation built on order, diligence, and reason can weather any storm—external or internal. But let complacency or blind ideology seep in, and even the mightiest empire fractures like brittle steel."

— Kurt von Schleicher,

speech before the Reichstag, Berlin, 1946

The Zweiter Weltkrieg, the Second World War, has ended. The Kaiser’s legions and their allies had prevailed in an unprecedented global conflict. Victory, while resounding in Europe at least, came at a staggering cost. At least 72.5 million deaths had resulted, with many more wounded or devastated. This toll reached upwards of 80 million when considering the satellite bloodletting of the Second American Civil War and the Chinese Reunification Wars.

The revolutionary French, Dutch, Nordic and British had fought to the last, leaving their Italian comrades to stand alone. Recognizing the futility of the struggle, these final holdouts signed away their existence in the Treaty of Venice. The Internationale, a one time bastion of world socialism, was utterly dissolved and condemned. The old order was reimposed, with ancient crowns restored, compliant authoritarian democracies and paternalistic orders installed amongst the vanquished nations.

As savage as the conflict had been in the west, which had once seen the syndicalist high tide approaching the suburbs of Berlin, in the east it had been cataclysmic. Ruled by the iron-fisted Boris Savinkov, the Russian State had waged a war of mass enslavement against its erstwhile Slavic neighbours and Germany. Through the bravery of the Reichspakt and its Austro-Hungarian allies, the Russians had been pushed back over the borders after years of occupation of great swathes of eastern Europe. The war would end in 1946 with the dropping of six atomic bombs on Russia, three on military targets, three on Belgorod, Bryansk and Moscow. In the days following this reckoning, Savinkov would be killed in a skirmish with a political rival’s forces, leaving Russia bereft of any hand strong enough to unite it. Once mighty Russia would splinter into competing warlords, inaugurating a new Time of Troubles.

While German arms had been carried from Brittany to Smolensk, the victory was not complete. The Japanese had waged war on Germany’s Pacific allies and colonies, taking these to establish for itself an empire to rival or surpass that of the Teutonic hegemon. The war’s aftermath also saw the alliances so instrumental to securing victory over syndicalism fraying. Austria-Hungary, unwilling to bend of German condescension, officially pulled away from the Second Reich’s orbit. The Anglo dominions of the former British Empire, united into a supranational federation, the Imperial Commonwealth, now seek to find new position in the world too. Other rising powers, such as newly awakened Brazil, or the freshly united India, the last of the syndicalist species, also advance uneasily into the second half of the 20th Century – a period some have taken to calling the German Century.

With so many questions left unanswered by the war, flashpoints have emerged across the globe, leading to simmering tensions between a rotating cast of great powers.

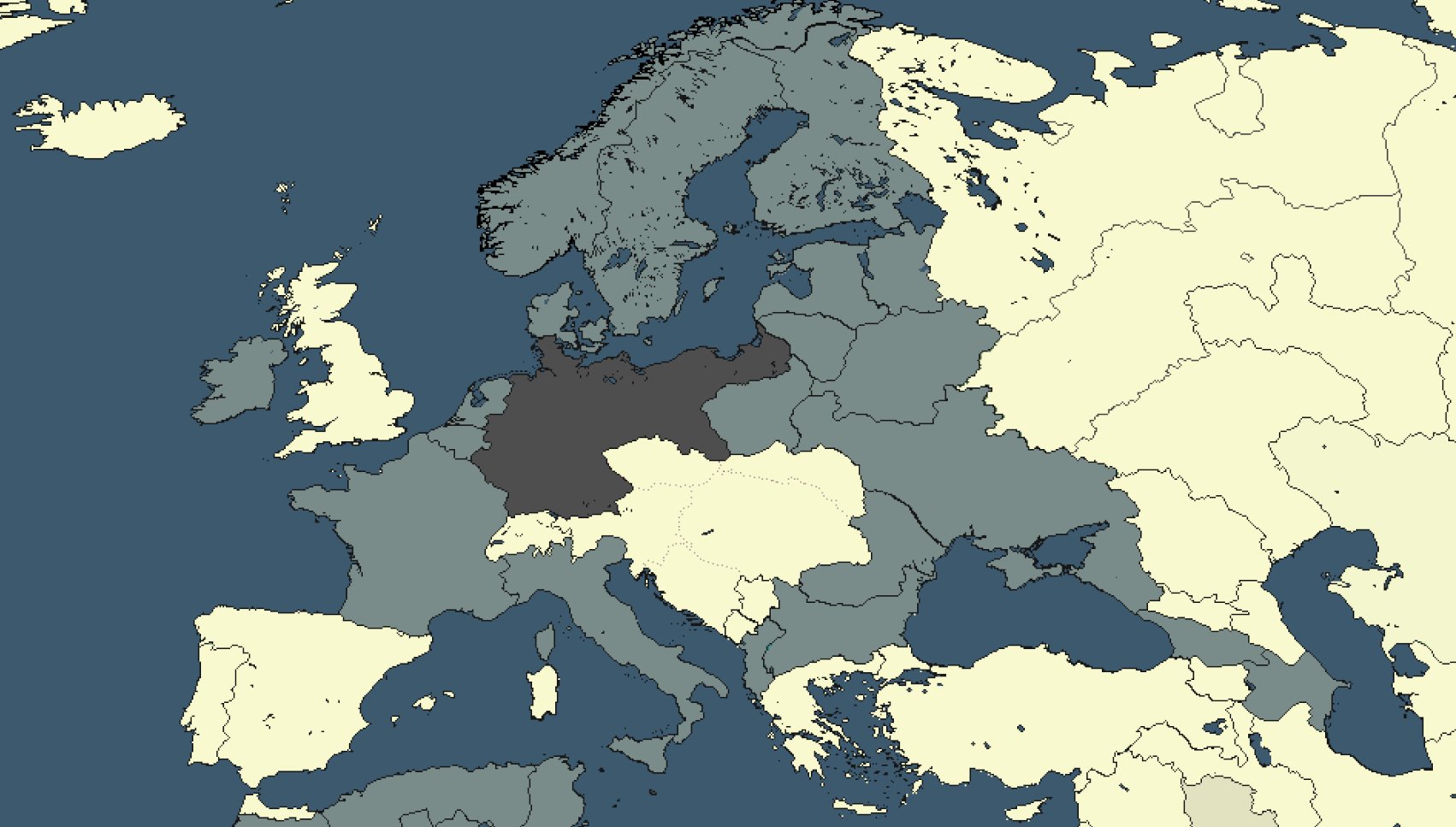

Europa

In the aftermath of the Second Weltkrieg Europe lies reshaped beneath the triumphant banner of German hegemony. At the heart of the reordered continent stands Mitteleuropa, an expansive sphere of German economic and political dominance stretching from the Atlantic coastlines of France to the plains of Ukraine. This network of client states, vassals, and puppet monarchies is bound together by Berlin with the pragmatic aim of transforming the continent into an integrated economic fortress loyal to the Reich.

Territorial adjustments have radically redrawn Europe's map. France, diminished and under tight German oversight, retains nominal independence but suffers a profound loss of sovereignty, especially in its eastern territories which remain garrisoned by loyal Reichspakt troops. The Low Countries remain firmly within Germany’s strategic orbit. The Austro-Hungarian Empire is increasingly fragile, its divisions evident as ethnic tensions simmer beneath Vienna’s imperial authority.

In the south, Italy has been reunited into the Italian Empire by the Borbone dynasty of Naples. While the throne is a shaky one, so long as it retains the favour of Berlin, it will stand. The old Savoy dynasty, fallen from grace after the First Weltkrieg, still rules in independent Sardinia while claiming the Italian crown. The Nordic countries contribute to the greater Germanic family, standing in privileged position in the eyes of the patrons of Völkisch ideology in the Reich. They provide crucial resources to the industrial heartlands of Mitteleuropa.

The Great Neutral, the Spanish Republic, has benefitted enormously from the war. A lender to the German government, it has reaped the rewards of standing aside while Europe tore itself asunder as interest payments come pouring into Madrid. Portugal, meanwhile, struggles to rebuild. An early adherent of the Entente coalition, the syndicalists aimed to close off the sea routes to Africa and Canada by garrisoning the small nation. Years of trench warfare would ensue in what became one of the wars most isolated and forgotten fronts, devastating Portugal.

In the east, the Ostwall nations, Germany’s allies since the 1920s, have largely benefitted save the exception of Poland. The Baltics have seen a compacted, yet more viable Lithuania arise, along with a more equitable arrangement for the old Baltic Dutchy, transformed into the Baltic Federation. White Ruthenia, renaming itself Belarus, has been vastly expanded with captured Russian territory. This arrangement is not as much a benefit as a concern however, given that the Russian population now rivals that of the Belarussian one within their own country. Ukraine too has spilled over into multiple former Russian oblasts and now stretches from Brest Litovsk to Krasnodar.

Poland has also seen its territory change shape, though its autonomy has been more kneecapped than ever. After a nationalist uprising killed the Polish king, August Hohenzollern, son of Wilhelm II, Germany had wreaked unholy vengeance upon Poland. A new king, Casimir V Hohenzollern, now rules a thoroughly scourged nation, though his marriage has thus far proven barren, leaving Poland’s dynastic future in doubt.

The former Russian State has fractured. Petrograd and its surroundings have escaped the fighting through continued German occupation. In the northwest, Nikolai Ustryalov, formerly the General Secretary of the Union for the Defense of the Motherland and Freedom (SZRS) ultranationalist party, has claimed Savinkov’s old title of Vohzd. He, along with generalissimo Anton Denikin, fight to continue the regime as its clearest successors. The shine has come off the SZRS however. While they managed to halt and even turn back Wrangle’s forces at the Battle of Yaroslavl, the continuity government is increasingly seen as moribund. Its troops are suffering from low morale and as its fortunes ebb, initial German supplies of oil, grain, flour and bullets have begun to slip away, leaving it isolated and starving.

Its immediate foe, led by Pyotr Wrangle, has seen success on all fronts until Yaroslavl. Emerging from the central plains of Russia, Wrangle, the most charismatic of the warlords, has promised national renewal and rebirth. Backed by conservative military officers, Russian nobles, and the Patriarch of Moscow, Anastasius, Wrangle’s forces have declared the restoration of the Russian monarchy and the renewal of a holy Orthodox realm. Framing the civil war as an apocalyptic struggle, Wrangle has dedicated his cause to saving the nation’s soul. A devout monarchist at heart, Wrangle has refused to claim the throne, naming himself Regent until a suitable Romanov heir can be installed. To irrevocably tie himself to the regime, however, he aims to marry his eldest granddaughter, Olga, to a Romanov prince in exile. His eye has fallen increasingly on the young and recently widowed Grand Duke Vladimir Kirillovich. Wrangle’s faction has attracted swathes of the population yearning for stability and divine favor after the hellfire of nuclear war.

Further south, leader of the former Ukrainian front, Mikhail Drozdovzky initially pledged his forces to Alexander Kazembeck’s rebellion against Vohzd Ustryalov. Kazembeck himself was killed in an ethnic uprising of Tatars, Bashkirs, Chuvash, Mari, Udmurts and others, who established the Idel-Ural Federation. This left Drozdovsky’s forces surrounded by enemies, but against all odds the Field Marshal has held out thus far, halting the Don Cossack advance on the city of Tsaritsyn. His troops, however, are strung out, underequipped, and on the verge of losing their grip on Voronezh, one of their last remaining industrial hubs. Along with the Cossacks, a smattering of other independence movements have sprung up to the south of Drozdovsky’s remnant, including the Mountain Republic, a largely Circassian affair, and the Caucasian Emirate.

Out east, yet another contender for Russia's leadership, SZRS governor Anastasy Voniatsky has established dominion over the rump Siberian territories not annexed by Japan's various interventions since the 1920s. Voniatsky was the main proponent and driver of 'industrial slavery', which saw millions of eastern Europeans forcefully uprooted and moved beyond the Urals into massive penal colonies that produced consumer and military goods for the Russian State. Under his direction, many of those millions would perish under the lash, or to the tortures and depravities of their jailers, let alone to the Siberian winter. For almost ten years, SZRS party members like Voniatsky lived like lords over a slave society. As the last days of the Second Weltkrieg saw Russia descend into civil war, the subjugated took their chances and initiated the largest slave rebellion in history. It was not long until German 'volunteer' regiments poured over the border to support this general uprising.

While the balance of power is slowly tipping towards Pyotr Wrangle’s New Holy Russia, the Second Russian Civil War is far from over.

Asien

Like the Russian Bear, the Chinese Dragon remains fractured. Like the pin coming out of a grenade, the downfall of the Qing government in the 30s saw an explosion of warlords vying for power. Over the last ten years, titanic efforts have been committed to stitching China back together again, leading to only three remaining powers who claim the title of ‘true government’ of China. The Beiyang regime rules over Manchuria and northern China as a loyal Japanese client state. Led by warlord Zhang Xueliang, this puppet regime claims to be China’s legitimate government. However, its people are restive under what they see as a puppet regime to Tokyo. In the south, the Kuomintang (KMT) nationalist government has solidified its power base, and it recently forged a pact with a northern Federalist faction led by Chen Jiongming (based in Shanxi). These two Chinese regimes have set aside their old rivalries to jointly challenge the Japanese-backed Beiyang Government in the north. Far to the west, even isolated Tibet has taken advantage of the chaos – expanding its frontiers into China’s western highlands with no opposition. The result is a China divided among three rival governments, each vying for supremacy amid the power vacuum.

Japan’s Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere now encompasses a web of allied states across the continent. These include:

- The State of Ceylon – the island of Ceylon, brought into Japan’s orbit in South Asia.

- Kingdom of Siam – Thailand’s monarchy and a key Japanese partner in Southeast Asia, expanded to include the Cambodian regions of former Indochina.

- Empire of Vietnam – a Japanese-protected state established in former German Indochina, reigned over by the Emperor Bảo Đại on the Thái Hòa Điện’s throne.

- State of Laos – a client state in Laos, carved out alongside Vietnam.

- Sultanate of Malaya – a Japanese-aligned sultanate governing the Malay Peninsula.

- Second Philippine Republic – a Japan-sponsored republic in the Philippines.

- State of Insulindia – a new Japanese-allied nation in the Indonesian archipelago (former Dutch East Indies).

- Far Eastern Republic – a Japanese puppet state in eastern Siberia, extending up to the Yakut River.

Through this extensive alliance network, Japan exercises hegemonic power from the Indian Ocean to the North Pacific. Japan has expanded its direct rule from Korea and Formosa to now include the superb naval base of Singapore and chunks of the Chinese mainland, largely among the former Legation Cities.

In Central Asia, the retreat of Russian power has allowed old realms and identities to resurface.

Mongolia, once a remote khanate, has aggressively expanded into Inner Mongolia, reviving dreams of a pan-Mongolic empire on the steppe. To the west, the vacuum left by collapsing Russia has been filled by a patchwork of restored nations. The

Kazakh Republic – born from the Alash Orda independence movement – now stretches across the steppe, pursuing its own destiny free from Moscow’s rule. Alongside it stand the revived Khivan Khanate in Khorezm, the Republic of Turkestan, and the Emirate of Bukhara further south. These states have largely reverted to traditional governance and ways of life, mirroring the region’s landscape before Russian conquest.

The Middle East has become a patchwork of independent and competing powers. This new order is precarious, defined by both the ambitions of local rulers and the cautious oversight of the victorious great powers. The region simmers with ethnic tension and revanchist ambitions.

The Ottoman Empire survives, but only as a shadow of its former self. After years of crisis and even a period of Russian invasion during the Second Weltkrieg, the Ottomans have regained their independence in Anatolia. The Desert Wa

r in the late 1930s saw a coalition of Arab revolts and enemy powers overwhelm Ottoman forces, stripping Istanbul of most of its Middle Eastern territories. In the aftermath, new states have arisen across the Fertile Crescent and Arabian Peninsula. Kurdistan has been proclaimed in the mountainous Kurdish heartland, realizing long-suppressed aspirations for independence. A republican Iraq arose along the Mesopotamian plain, confined largely to the Tigris-Euphrates basin. To the west, Syria has been established as an independent nation in the Levant. Further south, Arabia under the Hashemite dynasty (the former Sharifs of Mecca) now controls the Hejaz and much of the Arabian interior. The rest of Arabia is divided among longstanding local nations: Yemen in the southwest, Oman in the southeast, and the Trucial States along the Persian Gulf coast.

Amid these upheavals, the great powers have moved to safeguard their strategic interests. The Suez Canal, lifeline of global trade, has been declared a neutral free-trade zone. It is now administered jointly by Germany, France, and the Imperial, ensuring no single power monopolizes this critical passage.

South Asia is now dominated by a single, revolutionary power. India, or rather, the People’s Republic of Bhartiya (PRB) has found itself the world’s last great syndicalist stronghold. Having unified the subcontinent under a socialist banner, the Indian regime now rules from the Khyber Pass to Cape Comorin. The revolutionary government has extended its influence beyond India’s natural frontiers as well. Burma to the east was conquered and directly integrated as a border province of India, essentially serving as a forward march for the syndicalist state. In addition, sympathetic puppet governments have been installed in the neighbouring Himalayan and Central Asian states of Afghanistan, Nepal, and Bhutan, binding those countries closely to Delhi.

Emboldened by its regional supremacy, India is eager to export its syndicalist ideology abroad. Persia has become the newest arena of conflict, where Indian agents are funding and arming a syndicalist insurgency against the Qajar monarchy. Even as it agitates beyond its borders, India’s own political character is undergoing a careful transformation. After years under hardline totalist rule, the syndicalist leadership in Delhi is gradually reforming away from authoritarianism, attempting to build a more equitable and broad-based socialist system. This ideological softening is aimed at stabilizing the nation internally and improving its image abroad after the excesses of the revolutionary era.

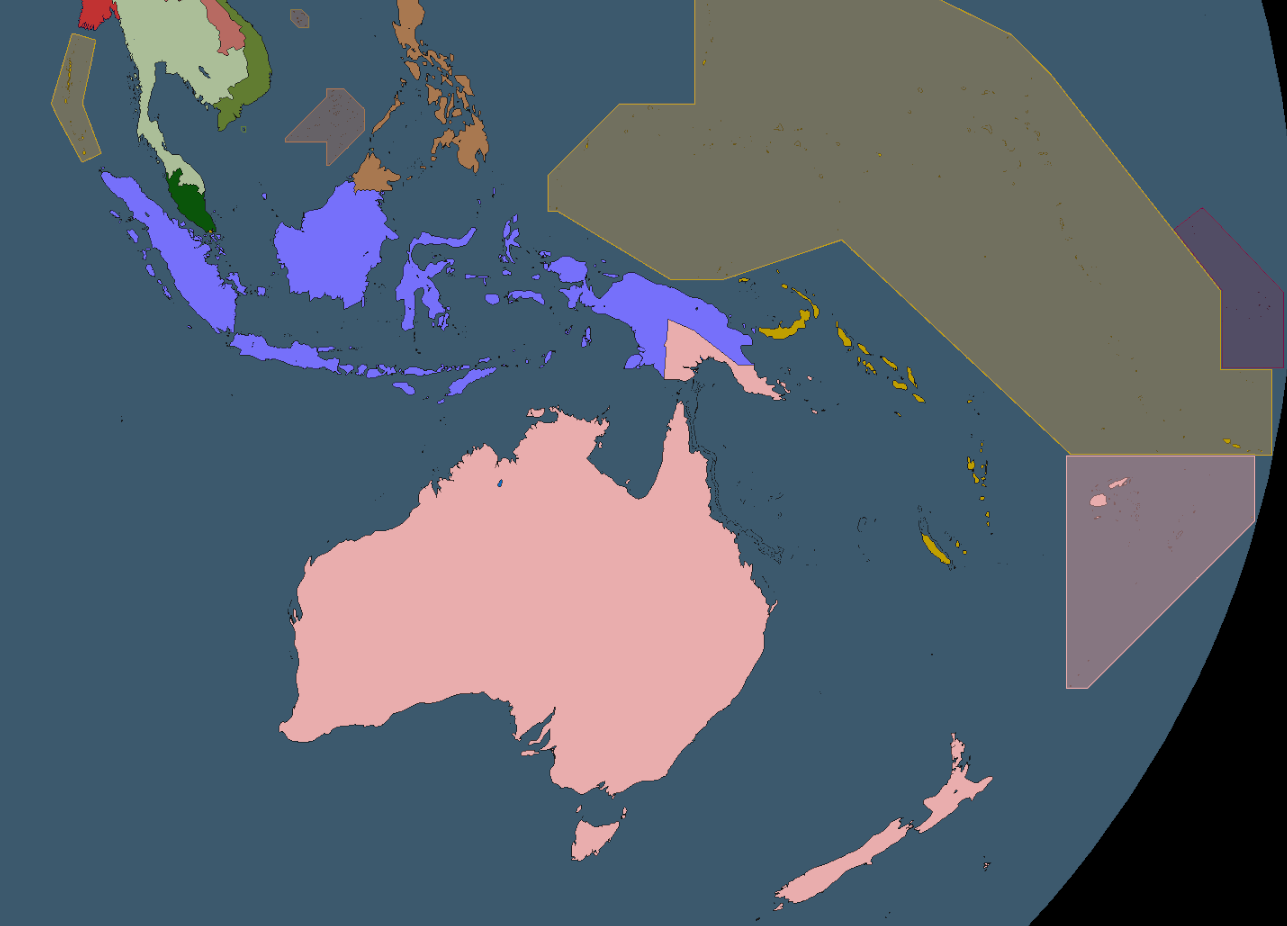

Ozeanien

Oceania, once a distant theatre of colonial rivalry, has been fundamentally reshaped by Japanese ascendancy. The sprawling Pacific territories formerly controlled by Germany and other European powers are now consolidated into Tokyo’s vast maritime empire. Under the banner of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, most islands—from the Solomons and Carolines to the Marshalls—are governed directly or through compliant protectorates loyal to Japan. Sukarno’s State of Insulindia rules over a unified Indonesian archipelago, serving as a powerful Japanese vassal, while the Second Philippine Republic struggles beneath the tight oversight of its distant imperial sponsor.

Yet Japan’s grip is not absolute. Australasia remains firmly entrenched within Imperial Commonwealth, wary sentinels standing guard against further Japanese expansion southward. Further east, isolated in the central Pacific, the Hawaiian Islands have carved out a precarious independence, sheltering remnants of America’s Pacific Fleet and a radical syndicalist government born from rebellion and desperation. This Hawaiian state, an improbable syndicalist enclave amid an ocean dominated by monarchies and empires, persists defiantly despite overwhelming odds through what support can be lent to it by India. Coveted by Japan and threatened by American revanchism, Hawaii serves as the Pacific’s greatest powder keg.

Amerikas

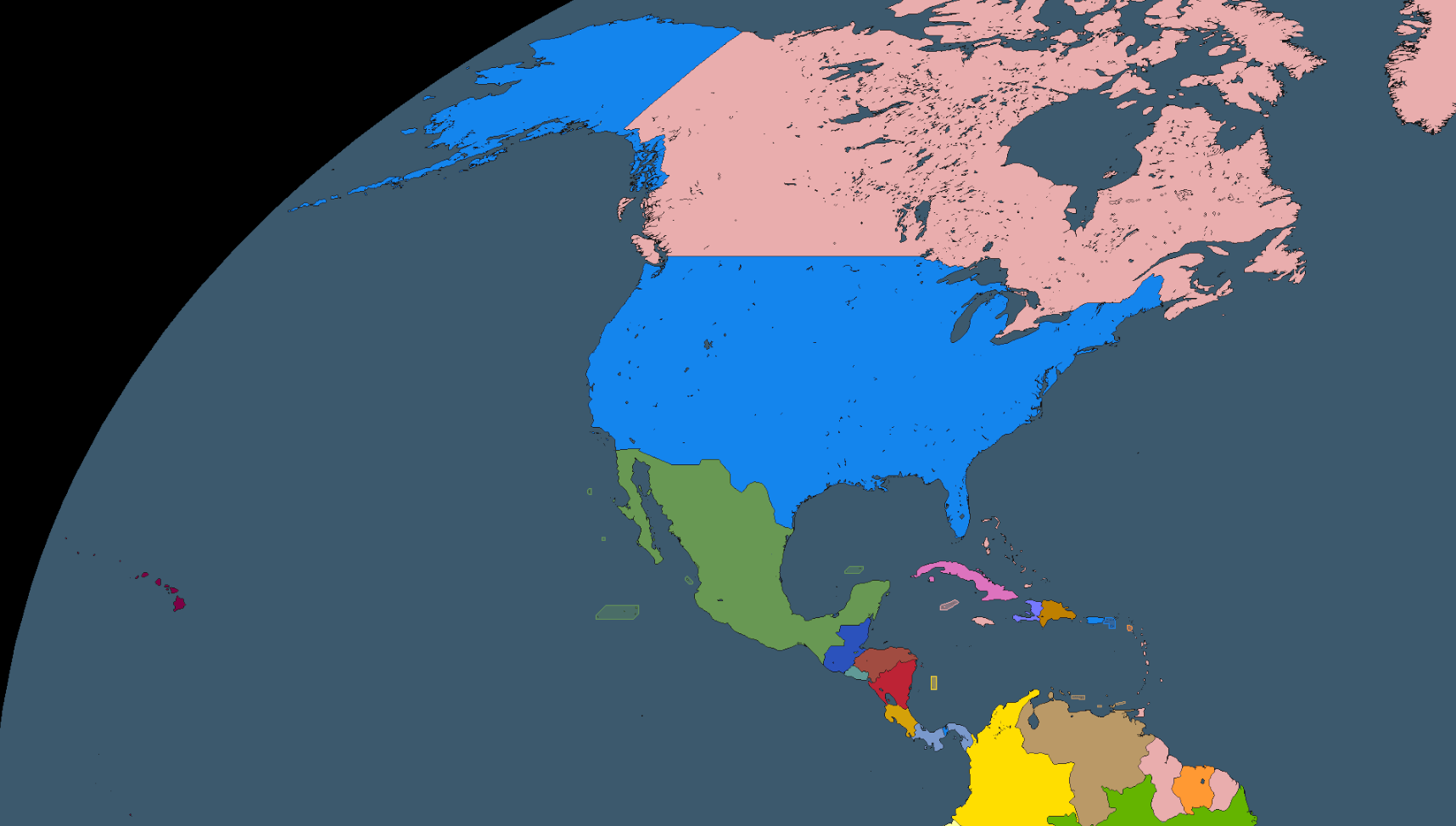

Across the Atlantic, North and South America have also seen profound upheaval. The United States, devastated by a civil war from 1937 to 1941 that toppled syndicalist President John Reed, remains under the tight yet slowly easing grip of President Douglas MacArthur’s military-backed regime. MacArthur, seeking a veneer of normalcy and economic recovery, prepares for a carefully stage managed third-term election in 1948 even while still combating isolated syndicalist and Minutemen insurgencies in Appalachia and the Michigan forests. Despite these radicals, most Americans, exhausted from their war and the subsequent famine, simply wish for peace and food. Under this compliancy, MacArthur has been forging ahead with monumental amendments to the Constitution in an effort to re-stabilize the country, increasingly nicknamed the ‘Bill of Order’. The question yet remains whether MacArthur has made himself into an American Cincinnatus or a Caesar, or perhaps yet something else.

To America’s north, Canada anchors the Imperial Commonwealth, maintaining its vigilance amid regional instability. The Imperial Commonwealth’s new constitution stipulates a rotating Imperial Parliament and Premiership every five years, meaning that Ottawa will have to give way for the first time to another member of the federation. This leaves uncomfortable questions for Canadians, who have now long seen themselves as the leaders of the former British Empire and one of the world’s movers and shakers of the last three decades.

Mexico, “liberated” from its syndicalist regime by Entente intervention, endures ongoing chaos as the Commonwealth-backed central government is overwhelmed by the centrifugal forces unleashed by Pancho Villa’s downfall. Centroamerica, previously unified under syndicalist influence, has been fragmented by Canadian efforts to dismantle the former regime and install more influenceable local governments.

In South America, the Lima-Rio de Janeiro Axis, an alliance between the Peru-Bolivia Confederation and Brazil, has decisively defeated syndicalist Chile and Argentina. The Confederation annexed northern Chilean coastal territories, while Brazil occupies Argentina’s Mesopotamian region, maintaining Buenos Aires’ compliance. Brazil has benefitted from the Second Weltkrieg more than any other nation save Japan. A late entrant to the war, it never suffered any combat on its own territory and has become home to millions of South American, North American and European refugees who have brought with them their wealth and influence. Its banks and government, like those of Spain, have raked in money, enabling generous social safety and public works programmes which has resulted in a buoyant feeling in the country. Signs of modernization are everywhere under João Mangabeira’s successor, President Juscelino Kubitschek. Most positive of all, Brazil’s central government has solidified its management of the country’s outlying regions, crushing corruption and reigning in its formerly rather independent military under the auspices of war powers. The millions of Brazilian veterans of the Second Weltkrieg, witnessing the country’s rise to prosperity, have had a newfound confidence and trust in governmental institutions who’s efforts have seen an unprecedented rise in the standard of living.

In the Caribbean, Cuba and Haiti remain strategically aligned with Germany, serving as geopolitical irritants to the recovering United States.

Afrika

Africa has become a continent divided. The last great imperial powers of the region, France and Portugal, struggle to hold onto their African possessions. In the desert and Sahel interior of their possessions, constant native restiveness is a drain on Paris’s already depleted coffers. Many veterans of the Weltkrieg, mostly Germans, have been hired to keep the peace, but the violence is increasing to the point where it its impossible for Europeans not to move around unless doing so in force. Portugal’s possessions are beginning to suffer similarly due to a lack of an ability to enforce Lisbon’s will on the territories.

In the African sub-Sahara, the former sprawling jewel of Germany’s colonial endeavours, has shattered. First due to the economic crisis of Black Monday, then the disasters of the Second Weltkrieg, Germany has never been in a position to reassert much authority over the region. What had been dozens of tribes, askari military juntas, restored kingdoms and the like have now been largely consolidated into fifteen officially recognised nations, though many more movements vie for survival beneath this canopy. Only Südwestafrika, Madagascar and the naval base at Djibouti have remained under German control. Most worryingly of all for Germany, France and Portugal is the sinister infiltration of syndicalist ideas from India. Pamphlets and fireside gatherings have been witnessed preaching the south Asian form of the ideology, particularly along the east African coast. To try to apply some form of stabilization to the region, Germany has attempted to co-opt some friendly governments, including that of Tanganjika, formerly the Ostafrikan colony, who’s military dictatorship is made up of askari soldiers, some of whom were veterans under the infamous Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck in the First Weltkrieg. These friendly governments have formed the Afrikabund. Where Germany cannot rule directly, it will attempt to install friendly partners through coercion, despite what others might have to say about this.

The world stands at the brink of a new age, one which can see it sent hurtling into any direction.

Author's Note: This is just a short re-introduction to the world as it is at the end of the German Century. Subsequent chapters will pick up the narrative and 'history book' thread where we left off.