Part One: Birth of the Kingdom

Chapter I: Pietro and the Founding of Savoie

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

"From his loins would spring a line of great Merchant-Kings; greedy, deceitful men bent solely on making coin, pious warriors who used gold to spread the boundaries of Christendom, and patrons of all arts using their immense wealth to bring cultural revolution to Europe, if not the rest of the world. It is surprising to know, however, that Pietro was little more than a militant priest who sought to rebel against a king he believed to be little more than a man too caught up in his own wealth."~ Ainsworth Carr, Contemporary Historian

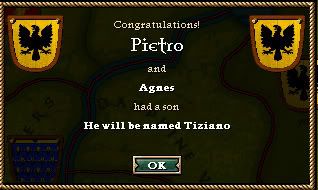

From 1066 to 1067 there are few recordings of what occured within the County of Savoie, the few texts which touch upon the early years of the di Savoie's claim that during this time Pietro's demesne saw much peace, though little prosperity. It can be safely assumed, however, that Pietro was quite busy, because in March of 1067 it is recorded that his wife began to become "round about her belly" and by November of that year Tiziano di Savioa was born.

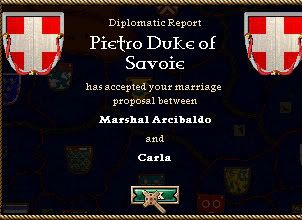

The birth of his first son pleased Pietro, and his mood remained buoyant when the next year, some time during late April, his wife, Anges d’ Aquitaine, sister of the Duke of Aquitaine, was proclaimed pregnant yet again. A few months into the pregnancy Pietro was called away from his wife and home, his king, King Heinrich went to war with the rebellious Duchy of Toscona. Roughly 4,000 to 5,000 men were levied from the counties and marched over the Alps to fight.

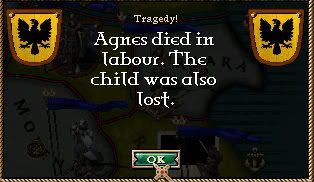

Pietro’s loyalty to his liege was questionable to begin with. As an Italian, he saw the distant German king as little more than a poor imitation of the long dead Charlemagne, though he realised that Heinrich sat upon a powerful throne, albeit one built upon brittle a foundation. Should his journals and letters of correspondence with various minor nobles be believed, during the campaign against the Duchess of Toscona, Pietro came into contact with many Italians who wished to throw off Heinrich’s yoke, believing that the distant king embezzled much of the good Italian people’s money. By no means did nationalist ideas cross Pietro’s mind; he simply found it blasphemous that the “Holy Roman Emperor” would live in such decadence. His distaste for his liege would grow from a dispassionate thought dwelling in the back of his mind, to a fiery hatred when he returned during mid-July of 1068 from the successful campaign, the victorious King Heinrich claiming the entirety of the Duchess's personal demesne, to find that his wife had died in labour.

While Pietro grieved his provinces thrived; according to merchant records settlements in both Savoie and Piemonte nearly doubled in size due to numerous serfs fleeing the shaky rule of Heinrich and the German lords he sought fit to rule over his newly claimed land. Pietro, however, was not doomed to living the rest of his days doting over a dead wife.In February of 1069 Pietro would marry Luitgard von Zahringen, daughter of the Duke of Carinthia and Pietro’s niece.

The remainder of the year passed relatively uneventful, though it should be noted that in April Pope Gregory VI called a crusade on the Egyptian held city of Alexandria. Most kings at the time, however, were far too preoccupied with keeping their vassals content and only King Magnus of Norway answered the Pope’s call. Within a few years, the Norwegians would capture Alexandria and not only destroy Egyptian power in the Middle East, but open the Middle and Far East to trade with Europe.

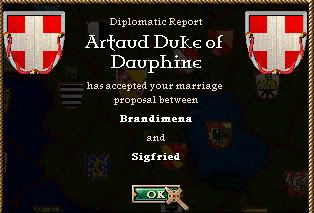

Luitgard was expecting her first child by late July of 1069 and by April the next year Pietro’s first daughter, whom the couple named Carla, was born, though she was born disfigured due to the closeness of her parent’s blood relation, and little is written about the child beyond her marriage when she came of age, so it can be assumed she was secreted away to some secluded nursery.

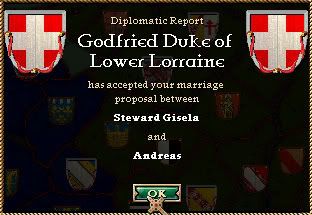

Few events of notes occurred from 1070 through 1075. Savoie and Piemonte prospered; attracting more and more merchants, three more children were born; Andreas, Dorthea, and Fausta in the years 1071, 1072, and 1074 respectively, and a minor argument between Pietro and Duke Bonifacio of Genoa, which would have major repercussions later on.

Pietro happily agreed, disappointing his wife and her father who had hoped for a Carinthia-Savoie alliance. Pietro was ecstatic over having an ally as powerful as Venice. He prepared himself for what he deemed to be a

Doge Guarinto, however, was terrified of such a war, having already committed his troops and much of his wealth to conquering the various Sheikdoms thrown into disarray by the collapse of the Egyptian Kingdom. In a letter the Doge urged Pietro to be cautious and prudent in his rebellion, suggesting that he take the peaceful path because of the simple fact that while most of the vassals were seeking independence, none of them would work in tandem due to personal enmities between one another. A great deal of thought was put into the Doge’s words and he replied to the Doge, promising him that he would “not bring down the armies of the Fat-King” upon them.“Glorious and bloody war against those who dare call themselves the leaders of Christendom, yet have little of Christ inside of them.”

Yet, his mind was still turned to war. Earlier that year, in January, the Bishopric of Valais broke free from the kingdom, and left itself vulnerable to attack. Pietro, who stated that the Bishopric needed to be put under the control of a stronger leader if it wished to survive the coming times, claimed the land and declared war by late April. He rallied roughly 1,500 men, promising the resistant towns who had prospered in peace and balked at the idea of war, more land for the farmers and thus more goods for them to sell. With that he marched on Valais.

Last edited: