Chapter 1: Birth of a Dynasty, rebirth of an Empirie.

Part 1: The Reign of Basil I (867-895)

Chapter 1: Birth of a dynasty, rebirth of an empire.

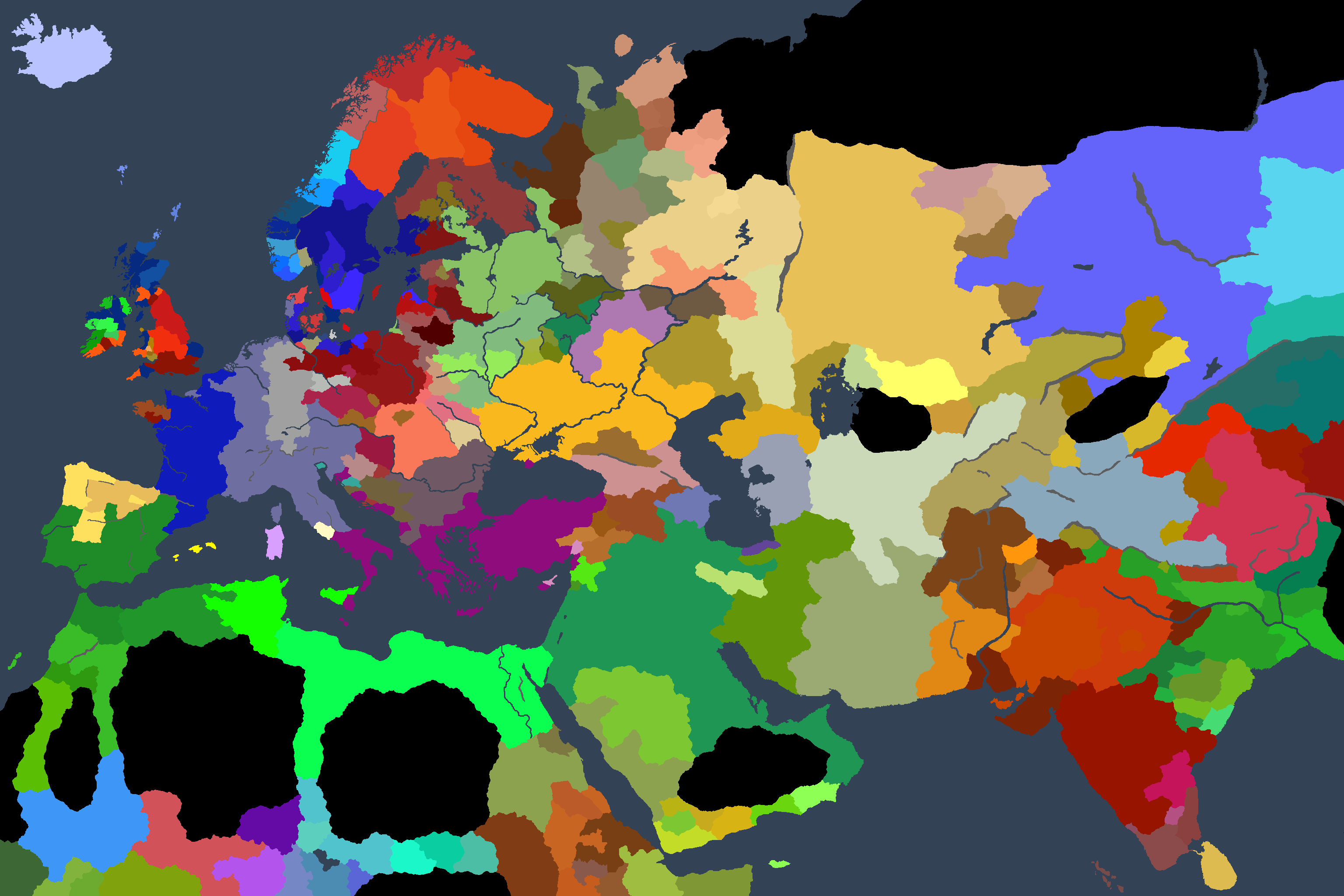

The world in the year of our lord of 867. Byzantine empire in deep purple.

Basileos the Makedonian was a peasant from the aforementioned province. His roots were, and are, a matter of hot debate. Some claimed he was a bulgar, others an Armenian. Some simply conformed themselves to the vague and generic label of ‘slav’.

Emperor Basileos I the day of his crowning the 1st of January of 867 AD

Despite his humble birth and murkier origins, the man proved an extremely capable. He caught the attention of many a powerful lord of the byzantine empire and, in due time, came to be the right-hand man of the emperor Michael VI. By 866 he was co-emperor to the Purple Born.

The Drunken Emperor, Michael III.

While a well-read man, Michael was a debauched being, unbound by the fetters of dutiful faith and in servitude to the vices of men, specially that of alcoholic drinking, which drove him apart from the people’s favor.

He attended the arts and letters, but not the armies and bureaucracy, earning him many enemies within the ruling castes.

The empire crumbled further under his careless rule and thus, harried by both the seldom united political factions of the Roman Empire and his own ambitions, Basileos ordered the assassination of Michael by the end of the year.

The emperor had been backstabbed a hundred and sixty-eight times. The investigation concluded with the only reasonable answer, wrote sardonically Baccos of Samos in his Chronicle:

"He fell down a flight of stairs."

Regardless, the man was denied all honours of state, forgotten and abandoned to his fate. Basil swiftly took both the crown and Michael’s mistress, Eudokia. Eudokia was a beautiful yet shrewd woman, over whom floated many rumours, for she had been married to Basil years after her affair to Michael began. Thus, her son Leo, allegedly Basil’s, was thought to be Michael’s. The Basileos certainly abscribed to that theory, and would drive their relationship.

Basileos had a solid understanding of the Imperial administration, as well as its diminished holdings.

Map of the Roman Empire at the dawn of the year 867 AD

Once the empire had spanned the entire Mediterranean basin. Covering from the western Iberian Peninsula to the far reaches of the Levant. From Africa in the south, to the upper reaches of Albion, up to Hadrian’s Wall.

Now, lamented Alexios of Thebes in his ‘The roman twilight: a tale of the decay of the 7th and 8th centuries’ "it was merely reduced Anatolia and the Aegean Sea. The Thracian border with the barbarous bulgars was less than a week away from the capital, most of Greece was dominated by the so called Epirotan Duchy and beyond that the Imperial authority didn’t extend beyond a few vestigial strongholds in the Adriatic and southern Italy."

The situation of the empire could only be labelled as dismal, a shadow of its former self, yet there was a glimmer of hope: the followers of the crescent moon and the sons of Carolus Magnus were divided now. Their once mighty empires had been fragmented into lesser, if still mighty, kingdoms.

As Baccos of Samos noted in his Chronicle, the moment was ripe for a driven leader to wake up the slumbering empire and prey on the now weaker neighbors. And, given whom gave Baccos patronage, that man could be none other than Basileos .

There still remained the Bulgar threat to the north, though, and the kingdom of the bulgars was a most heinous polity, wrote Alexios of Thebes.

But it was not the bulgars that would crackle the scourge of war against the Roman Empire for the first time in Basileos’ rule.

That privilege befell on the Emirate of Sicily.

Chapter 1: Birth of a dynasty, rebirth of an empire.

The world in the year of our lord of 867. Byzantine empire in deep purple.

Basileos the Makedonian was a peasant from the aforementioned province. His roots were, and are, a matter of hot debate. Some claimed he was a bulgar, others an Armenian. Some simply conformed themselves to the vague and generic label of ‘slav’.

Emperor Basileos I the day of his crowning the 1st of January of 867 AD

Despite his humble birth and murkier origins, the man proved an extremely capable. He caught the attention of many a powerful lord of the byzantine empire and, in due time, came to be the right-hand man of the emperor Michael VI. By 866 he was co-emperor to the Purple Born.

The Drunken Emperor, Michael III.

While a well-read man, Michael was a debauched being, unbound by the fetters of dutiful faith and in servitude to the vices of men, specially that of alcoholic drinking, which drove him apart from the people’s favor.

He attended the arts and letters, but not the armies and bureaucracy, earning him many enemies within the ruling castes.

The empire crumbled further under his careless rule and thus, harried by both the seldom united political factions of the Roman Empire and his own ambitions, Basileos ordered the assassination of Michael by the end of the year.

The emperor had been backstabbed a hundred and sixty-eight times. The investigation concluded with the only reasonable answer, wrote sardonically Baccos of Samos in his Chronicle:

"He fell down a flight of stairs."

Regardless, the man was denied all honours of state, forgotten and abandoned to his fate. Basil swiftly took both the crown and Michael’s mistress, Eudokia. Eudokia was a beautiful yet shrewd woman, over whom floated many rumours, for she had been married to Basil years after her affair to Michael began. Thus, her son Leo, allegedly Basil’s, was thought to be Michael’s. The Basileos certainly abscribed to that theory, and would drive their relationship.

Basileos had a solid understanding of the Imperial administration, as well as its diminished holdings.

Map of the Roman Empire at the dawn of the year 867 AD

Once the empire had spanned the entire Mediterranean basin. Covering from the western Iberian Peninsula to the far reaches of the Levant. From Africa in the south, to the upper reaches of Albion, up to Hadrian’s Wall.

Now, lamented Alexios of Thebes in his ‘The roman twilight: a tale of the decay of the 7th and 8th centuries’ "it was merely reduced Anatolia and the Aegean Sea. The Thracian border with the barbarous bulgars was less than a week away from the capital, most of Greece was dominated by the so called Epirotan Duchy and beyond that the Imperial authority didn’t extend beyond a few vestigial strongholds in the Adriatic and southern Italy."

The situation of the empire could only be labelled as dismal, a shadow of its former self, yet there was a glimmer of hope: the followers of the crescent moon and the sons of Carolus Magnus were divided now. Their once mighty empires had been fragmented into lesser, if still mighty, kingdoms.

As Baccos of Samos noted in his Chronicle, the moment was ripe for a driven leader to wake up the slumbering empire and prey on the now weaker neighbors. And, given whom gave Baccos patronage, that man could be none other than Basileos .

There still remained the Bulgar threat to the north, though, and the kingdom of the bulgars was a most heinous polity, wrote Alexios of Thebes.

But it was not the bulgars that would crackle the scourge of war against the Roman Empire for the first time in Basileos’ rule.

That privilege befell on the Emirate of Sicily.

Attachments

-

upload_2019-8-18_22-15-9.png192,4 KB · Views: 41

upload_2019-8-18_22-15-9.png192,4 KB · Views: 41 -

upload_2019-8-18_22-18-52.png407,9 KB · Views: 21

upload_2019-8-18_22-18-52.png407,9 KB · Views: 21 -

upload_2019-8-18_22-19-5.png368,4 KB · Views: 18

upload_2019-8-18_22-19-5.png368,4 KB · Views: 18 -

upload_2019-8-18_22-19-15.png372,5 KB · Views: 22

upload_2019-8-18_22-19-15.png372,5 KB · Views: 22 -

upload_2019-8-18_22-20-8.png374,1 KB · Views: 18

upload_2019-8-18_22-20-8.png374,1 KB · Views: 18 -

upload_2019-8-18_22-20-35.png388,6 KB · Views: 21

upload_2019-8-18_22-20-35.png388,6 KB · Views: 21 -

upload_2019-8-18_22-20-50.png393,5 KB · Views: 21

upload_2019-8-18_22-20-50.png393,5 KB · Views: 21 -

upload_2019-8-18_22-20-58.png414,9 KB · Views: 19

upload_2019-8-18_22-20-58.png414,9 KB · Views: 19