The Salt Spray

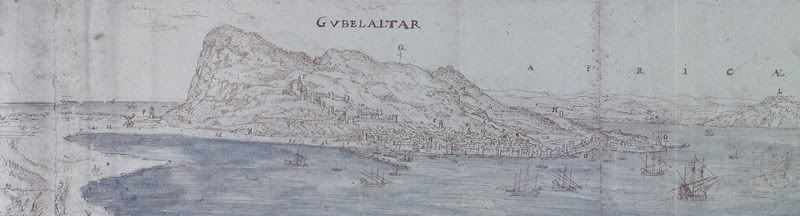

Gibraltar, 17th April 1407

Sound travels far over calm seas. Rohan had known this, but never had he truly fathomed it as he did now. His cannons, all eight of them, supplied by his Aragonese allies, Genoese war-profiteers and comandeered from the Castilians themselves, would soon sing their own raucous symphony along with the trebuchets in order to disturb the sleep of the defenders of Gibraltar, but for now, he listened to another tune.

Even with the help of advanced siege engines, Gibraltar remained a tough nut to crack.

From across miles and miles of Atlantic sea, turned red gold by the setting sun, came the dull report of cannonfire, just on the edge of hearing. Others, apparently, had stopped their activities to listen in as well, for silence ruled among besieger and besieged alike. At times, François thought he could see the flash of gunfire, hear the crack of splintering wood and shouting sailors, smell metal and burning blackpowder, feel the thrill of battle and taste death on the wind. Other times, he was simply blinded by the sun and his nose filled with the stench of a five thousand man camp.

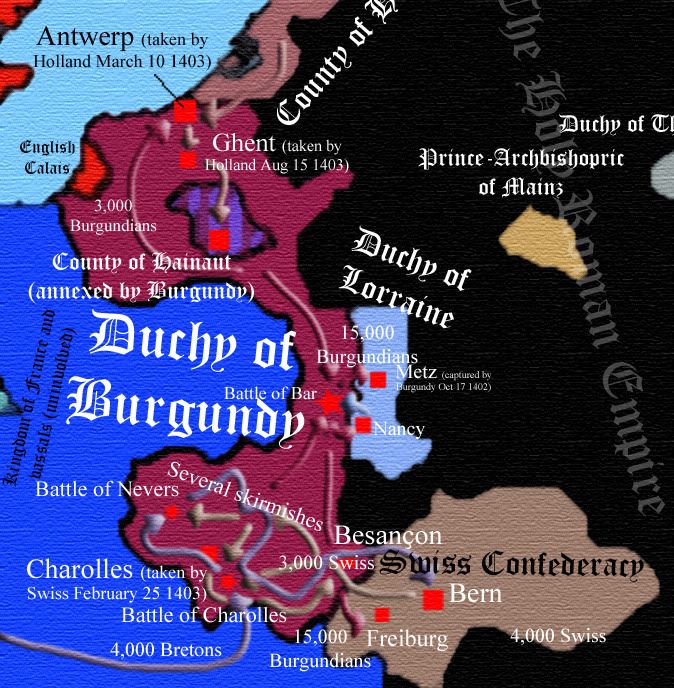

He couldn‘t make up his mind whether he belonged out there or here. He was not cut out for siegecraft. Pitched battles against a fluid enemy were his strength. On the other hand, he got sea-sick. Still, it irritated him that he was stuck here pelting some unimportant backwater while Bretons were giving up their lives in a real fight.

Presently, lieutenant Erwan de Tromelin appeared from behind him.

“Sir? Senior Captain Ripoll has requested an audience with you. Down at the dock,” he reported. When they had set up their siege camps and the naval blockade, a crude harbor had been constructed by the shore to receive supplies from the ships. It was too shallow to allow the vessels to actually dock, but it facilitated transporting with the use of rowboats from the ships anchored outside.

“Indeed?” mused Rohan, furrowing his eyebrows. Summoning him to the piers was unusual, as they usually conducted meetings in the command tent of the siege camp. Now that his attention was caught, he also noticed a lot of activity down there. “How is the supply situation?”

“Good, sir. There should be ample ammunition for the night’s barrage.”

“Excellent. Make the necessary preparations. I want to hear bombarding as soon as the sun dips below the horizon.” De Tromelin nodded and set off. Rohan took another moment to regard the red sunset, then found himself a horse and trotted down to meet the Aragonese senior captain.

Gaspar Ripoll and he had become fast friends after the Battle of the Gulf, where the Aragonese galley fleet had been hard pressed by the Castilian fleet of larger, ocean-going vessels until the arrival of Breton and Portuguese reinforcements. Rohan had patrolled the shores for survivors and Castilian ships trying to find shelter and repair. He and Ripoll had then met in Valencia to celebrate the victory, and would co-operate closely in the following campaign in Andalusia, the Aragonese navy supporting and supplying the Breton land force.

Portuguese and Breton ships were crucial in securing naval dominance in the first Spanish War.

He found the Senior Captain barking commands at stevedores carrying barrels and crates on to rowboats of all sizes, and Rohan saw a fleet of them moving back and forth between the galleys anchored off shore. He also noticed the galleys were not ringed around the town as they had been.

“

Bona tarda,” the Catalonian greeted as Rohan stepped off his horse and clasped his hand. He did not smile.

“

Bona tarda, Gaspar,” replied the Breton, “You’re off to join the fight?”

“Aye, my friend. I can’t stay here while a battle rages off the horizon.”

“I feel the same way,” replied Rohan. He could no longer hear the distant drums of battle over the calls and shuffling of the dockworkers. “You’re taking all the ships?”

Ripoll gave a small grimace and looked out over the sea towards his fleet. “Aye. We can always replace the blockade, but if the Castilians should win the waves…” he sucked in air through his teeth.

“You need every ship to make sure that doesn’t happen,” the Breton agreed, nodding.

There was a pause, until Ripoll shouted at a crate carrier and pointed animatedly, then turned to his friend. “I have left a part of our supplies for your use, as we do not plan on a long voyage.”

“Gaspar,” began François, holding up a hand and smiling, “I handled Switzerland without your help. I’ll handle Gibraltar.”

Gaspar laughed. “Aye, you better. I’ll see you in a few days.”

“

Que vagi bé,” said the Breton, clasping Gaspar’s hand.

“You take care, too, my friend.”

François watched as the last of the rowboats, Ripoll among them, hurried out to the fleet and then as the 18 galleys and Ripoll’s larger flagship, the captured Castilian warship

San José, chased the last red sliver of sun into battle. Just as the sun vanished and the ships became distant shadows, the distant

doom doom of the Breton artillery began as the siege of Gibraltar crawled onwards.

The next week dragged on. There were messages and status reports to read. Granadan emissaries offered them feasts and weapons, hoping that a weakened Castille could give them hope of surviving the Reconquista. The Gibraltar defenders established a secret harbour on the other side of the peninsula where fishing boats were able to deliver supplies from Andalucía. It was too small and the route too long to fully sustain the town, but it slowed the siege down, so Rohan sent a sortie to close it off and seize what they could find.

A week after Ripoll had left, sails were spotted on the horizon as the sun crept up above the horizon and the guns gradually fell silent. It was a calm morning, so the ships travelled slowly and for two hours the air was filled with a pregnant silence. Were they Castilian ships, or Aragon or Breton? These questions were on everyone’s minds as the shapes gained form and size excruciatingly slowly. Finally, a cry went up from the crude docks, then another and another. Like a wave, it spread through the ranks of the besiegers until everyone was shouting.

“The Ermine flag!”

“Victory!”

“Long live King Martin and Duke John!”

Rarely before had François been so relieved to see the black and white flag of Brittany. As the fleet drew nearer he marvelled at the majestic sight of the large Breton carracks and the smaller, lower, but twice as numerous Aragonese galleys. Together, they dominated the scene.

The fleet laid anchor off shore and spawned a child fleet of dozens of rowboats heading for shore, but when Rohan arrived to meet them, neither Captain was there to greet him. Finally he met the Aragonese quartermaster of the

San José, who informed him that Ripoll had been wounded in the battle and requested Rohan’s presence aboard the ship.

It was a long slog of rowing to the large Spanish vessel, even with six rowers and two passengers. As he passed the ships of his own countrymen he found not cheering victors but grim faces, often bandaged, aboard ships that looked like they had been through hell and back. One ship had lost her central mast and several had holes in their sides and the black marks of fire on their decks. He spotted a wooden prow statue of a horse where the head and front half had been torn off by some force.

The

San José, in contrast, was in fairly good shape, as were the galleys. Helpful hands pulled him up the rope ladder thrown down to the rowboat and onto the deck. He found Ripoll in the captain’s quarters, flushed and glistening with sweat, his leg bandaged and elevated. There was another man, as well, who introduced himself as Primel de Gourcuff, first mate of the

Chameau, flagship of the Breton fleet.

As they began to talk, the story of the battle began to unfold.

“

Those no-good Portuguese scum!” snarled Ripoll.

“The Portuguese –somehow- were informed mid-fight that King John of Portugal had negotiated a peace with King Henry of Castille and Leon,” de Gourcuff explained, seeing Rohan’s nonplussed expression. “Their sixteen ships left the fight leaving our six ships alone to deal with Castille’s eight.”

“Bastards,” growled Rohan.

“We were able to hold on long enough for Ripoll to arrive with reinforcements, but Senior Captain Similien de Bain was slain when

San Juan boarded

Chameau, although we were able to turn the tables and capture it ourselves. The captains of the

Portefaix and the

Argonaute were slain by cannon and crossbow, respectively.”

“So who’s in command?” François asked.

“I am,” answered Ripoll, grimacing, “temporarily, until you, as a senior officer, can appoint a new commander of the Breton fleet.”

“And what happened to you?”

Ripoll grinned. “Cannonball. We had them on the run, but I wanted a prize for myself, seeing as you Bretons had already taken two, so I gave chase to the

Neptuno. It was all but crippled, but they had a stern cannon. They only managed one shot, but it glanced against my shin.”

Rohan grimaced. Even a glancing shot from a cannonball could be fatal. “How are you holding up?”

“Poorly. I’m alive now, though. That’s all I can ask for.”

“Come on land, I’ll have my physicians take a look at you,” François began, but Gaspar cut him short with a wave of his hand.

“My own chirugeon is good enough and I don’t think I’m fit to be moved. Besides, if I’m about to die I’d rather do it with a boat under my arse.”

“You’re not dying,” stated François, but Gaspar only snorted, “but I’ll send them out here anyway.” Ripoll rolled his eyes but raised his hands in surrender. François grinned, “I’d stay with you, but…”

“You get seasick, I know,” Ripoll smirked.

Five minutes later he was back on the rowboat, already feeling a queasiness in his stomach. De Gourcuff was with him, but they exchanged few words, François too intent on keeping his nausea in check and thinking how he was going to appoint a new senior captain.

“I wonder how fair that horse may have been before it was shot to splinters,” he mused, looking at a shredded prow as they passed it.

“That actually used to be an argonaut, sir.”

“No shit? Couldn’t tell that at all.”

There was a pause, then the quartermaster spoke up. “What a stupid war.”

“Aren’t they all?”