"Damn it!" the professor exclaimed. Julius Caesar Augustus, a well known professor at the university, had another article due on Monday. Problem was it was 3 am Monday. "If only I had a secretary... a nice, well-bosomed... red-headed one. Then I could get these annoying articles done on time." He finished the last of his current glass of port and turned to the empty page before him on the computer. He turned then to his notes again.

He was doing a series of articles on the County of Toulouse and Early Medieval France. Fortunately, he had done alot of field research on the topic a few years ago. "Just dredging through these notes should give me a good piece to turn it by 8," he said confidently. "Just call William of Normandy 'Bastard' enough times and the French will eat it up." He began typing at a high tempo, which was unusual for him, and then poured another glass of port.

***

Toulouse and the First Anglo-French War

by Prof. Julius C. Augustus

Toulouse and the First Anglo-French War

by Prof. Julius C. Augustus

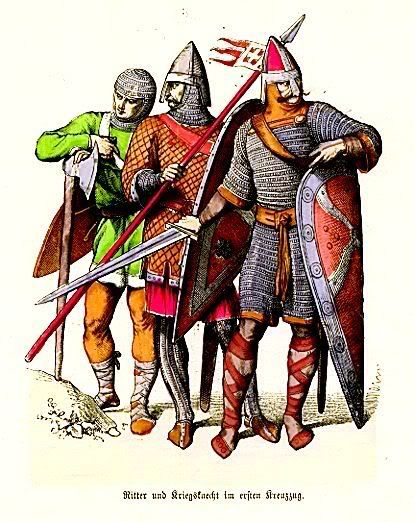

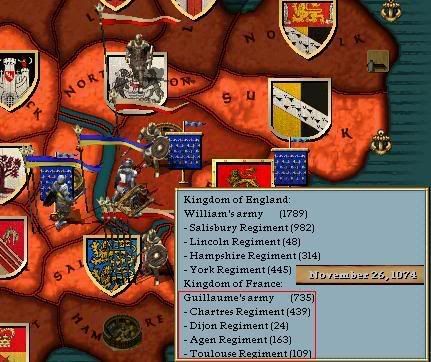

Four short years after the end of the regency of his mother, Anne of Kiev and after William the Bastard's incredible conquest of England, Philip I of France began an audacious war to bring Norman power to heel in Northern Europe. He was only eighteen, untested by the rigors of war, and the nobles of France continued to counter the reviving power of the Monarchy with ever fiercer disloyalty. Yet, common hatred of the Normans, desire for new lands and titles, and fear of strong English power drove even such arrogant men to take arms with their liege and fight for five long years against the enemy. Notable among such men is William of Toulouse, Count of Toulouse, Marquess of Provence, and Duke of Narbonne, whose star rose greatly because of the war, making him much praise by both the King and his fellows. The true effect of the war on the two parties is best noted if one looks behind the battles and words of the kings and looks at the effects of those battles upon the noblemen who survived. William of Toulouse and his lands will serve as a case study in this effort.

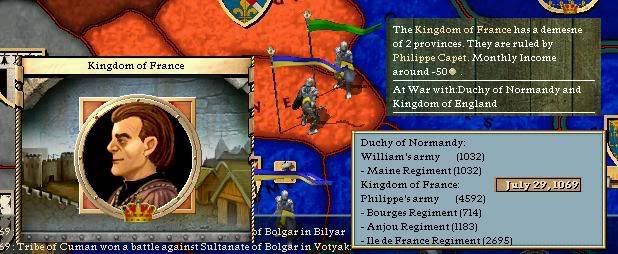

Fig 1. King Philip I of France and the Battle of Le Mans, July 29th 1069

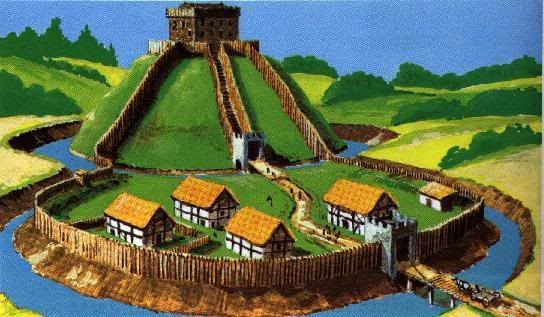

When Philip I declared war on the Duchy of Normandy in May of 1069, he intended nothing less than reversing the Treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte, signed in 911 by his predecessor Charles the Simple, which had given the Normans land in Neustria and ordered them to protect Charles' kingdom from any new invasion by Vikings. No written records, even at that time, survived concerning the creation of the Duchy of Normandy. Thus, Philip claimed the Duchy to be an illegal creation and crossed into Maine with an army of about 4,600 men to make it so. Robert Curthose, son of William the Bastard and now Duke of Normandy, quickly sent word from Rouen to London of the “vile action,” to which William was forced to mobilize the men of his freshly conquered kingdom against France. The French crushed the Ducal armies, first near Le Mans in Maine on July 29th and again on October 26th at Arques. Two days later, Duke Robert met King Philip before the city to capitulate; he ceded Arques to the Crown and secretly swore fealty to the King. Normandy was knocked out of the war and the Kingdom of the English now stood alone.

To this point, though they had been called early in June, the armies of the vassal Dukes had not seen battle; only men from the royal demesne had been used against Normandy. For example, William of Toulouse and his men are recorded as only arriving in Normandy about the time of the peace being signed with Robert Curthose. Philip knew how these men could be used, though, even with the fighting in France at an end. He dared to attempt to repeat William the Bastards' brave (or foolhardy) action of only four years before. Philip I of France was going to invade England.

***

Julius finished his glass of port and put it aside for the bottle. He was wished he was teaching his class instead of writing, but he was on sabbatical this semester and he knew something big was expected for him if he was going to get tenure upon his return. Articles always helped in this manner, but they were increasingly a chore. "A chore I could do without!" Julius gulped down was was supposed to be dinner wine and stumbled down the hall to his bed. That would be enough for tonight...