--Journal 15; 7/19/19--

**August 15, 1275**

!King Guichard de Boulogne! [124]

In the midst of all of this, I received a letter from my eldest sister, Isabeau, queen of the Maghreb, wife of King Eustache, expressing her condolences for our mother’s death. And, while the message did include word from her husband and father-in-law, our uncle Guichard, my namesake, for Father, I noticed that she had not made any mention of him: despite being the firstborn, she had been a woman, and Father hadn’t paid much attention to Isabeau after my own birth, even after I had been sent off to Alexandria. From what Mother had said, Aunt Bourguign’s inheritance had soured my Father’s relation with his brother, so he had sent Isabeau off to marry Eustache to mend their relationship. But this meant that I had never met my sister in person, as the weak realm of the Maghreb hadn’t the coffers to send Isabeau back to her home, and so, she was as much of a stranger as any other foreign ruler.

Vowing to arrange a trip to the shores of Africa to meet my sister, I turned my attention to the upcoming battle, awaiting news from Amedeo’s condottieri as my scouts brought news from the Seine. Despite my fears, it appeared that the Almighty had seen to my salvation, as only a portion of the Norman force had been able to cross the river before the bridge suddenly collapsed, leaving the remaining two-thirds of their army stranded in the plagued country, and unable to attack. With a prayer to God in thanks for His divine protection for His most divinely appointed King, I ordered the attack against Alexander’s, a crossing of the Eure, hoping to seize the initiative and gain a numerical advantage over the Normans.

We struck on the first day of September, marching through the desolated countryside as we found the Normans camped beneath castle Gaillon, an old fortification that had stood for hundreds of years, built to protect the Norman lands from French invasion. The irony wasn’t lost on me as we launched the assault, forgoing our skirmishing as we launched into the assault, men at arms and horsemen enclosing on the Normans, a bloody and cruel melee beneath grey skies. I could only watch as our men descended upon them, ever-growing as the Normans held their ground, reinforcements slowly crossing from Le Manet bridge. The fighting was slow, and my commanders could see the growing frustration and tiredness, and so we ordered a withdrawal to organize and regroup, while the stumbling forces of the Normans fled or tried to find their strength.

It was then that a rider arrived, bearing new for me to hear: I had hoped that God had given us another blessing, and that Amedeo had arrived to take the field—but, the rider had a sour look as I recognized the man from Melun, Edouard, one of Agnes’ personal messengers. With terrified words, he said that Alexandre had been found with the buboes, and, despite Agnes’ protests, he had been quarantined. I immediately called for my horse, and gave command of the field to Thomas Karling, but my lords pleaded with me: my crown lay on the field here, and the fate of my son lay with God; let us men do what we could here, lest I lose my kingdom and my heir. As I prayed that he had one ounce of Hugues’ Mithridatic strength, Philippe de Valpergue reported that our tired men had begun to return to the field, their strength recovering, whilst our horses were ready to be resaddled.

Frustrated with their slow pace across the Le Manet bridge, the Normans had sought other methods of crossing, and, having acquired some rowboats from somewhere down the Seine, had begun to ferry their troops across, trying to regain a solid position on the western bank. But then, as one of the boats sank beneath the river, the knights began to leave their mail with their van, carrying just shield, helm, and sword—easy targets. It was then that we launched our second attack, cutting into their weakened lines, our crossbowmen bringing the riverboats from Gaillon, using them like pavise before taking to the water to combat our unarmored foes. It was by now that we had taken the western shore of the bridge, and, unleashing my frustration and anxiety for Alexandre upon the Normans, lashing out as I led my horsemen in pursuing the enemy route across the bridge.

The Normans were scattering, toppling into the Seine as they tried to escape our lances, while their men aboard their riverboats were bombarded with bolts, or sinking from the weight of their route. But, while most of the enemy on the far side of the river had lost cohesion, some still held firm, and, crashing into them, I was amidst the melee, striking down at the dismounted Norman knights. Philippe was at my side, turning aside blade after blade as I roared with anger, my mace shattering helms and skulls alike. It was in the midst of this that I had a spare moment of serenity, the sun breaking through the clouds to shine across the Seine. Taken aback, I felt the warmth of the day and, despite the carnage around me, felt a greater sense of my physical being, my sense of place, and God’s judgement upon us all. But then, there was a flicker in the river, and the sun’s light brought a sudden reflection into my eye, a sudden distraction—and a costly one.

In my retrospection, I didn’t hear Philippe call out to me, as a Norman knight, unidentifiable without any surcoat or heraldry, took a bold stab with his spear, piercing my side. As I recoiled from the strike, the wedged end pulled, and I felt a tear through my ribs, and my earlier serenity had been lost. To this, the Norman pulled back now, giving a cheer as I dropped my weapons, grasping at the weapon within me, and, in a moment of spite, my anger overcame my pain, pulled it out. While Philippe and my armsmen rushed to my side, I hadn’t lost sight of the unknown Norman, and, despite the wound being on that side, I threw the spear, like a javelin, over the heads of my comrades. As my vision darkened, I saw that it had failed to hit its mark, impaling itself into the dirt as I saw several horses ride after my murderer.

With the panic and the pain, my consciousness faded between varying states, and, amidst the faces of those whom I could only recognize, at best, I later found myself in Gaillon castle, a surgeon picking at my wound as a priest prayed, and my men watched. With a wooden dowel between my teeth, I roared and struggled against the bonds that had been placed upon the bed as the physician pulled out more bloodied bits and pieces from my innards. I was given a brief respite only to find a wine sack thrust into my mouth, coughing as it flowed into my lungs, and I was met with the unexpected taste of a Norman cider. I hadn’t the mind to appreciate the irony as the dowel was forced back into my mouth, and, as he dug into me once again, I realized that I had no sense of hearing, the pain rippling throughout my body, even burning its way into my ears. My men appeared to be discussing something as this happened, and, it was then that I noticed a different face amidst their number: Amedeo with some of his mercenary captains. Glaring at them, I turned my pain into anger at the condottieri, as it was their fault that I had to engage the enemy personally—that was why I had hired them!

For all the hate I could muster, it was not enough to block the pain, and so, after another round of cider, which was more palatable now that I could expect it, the darkness returned and I hadn’t a thought until I woke up, the Duke of Lower Brittany at my side. As the Karling called for my attendants, my first question was that of the battle, to which Thomas replied had been a worthwhile success: despite our numerical disadvantage, we had taken some 7 thousand of the enemy, and, of the 10 thousand survivors, most had scattered about the country, seeking plunder and profit now instead of conquest. With my crown safe, I could at least breath some relief as I asked of the fate of our men, to which Thomas said we had lost half that of the Norman number, though they were galvanized and, even now, Phillipe de Valpergue and Geraud de Guines had taken their men west and east, respectively, intending to hang ever last Norman bandit. But, speaking of our troops, I asked of Amedeo—was the cur still in our employ? I sought to hang the man too, but Thomas said that the arrival of the condottieri broke the last resistance of the Norman. While the Italians sought payment for their services, Thomas had given them the share of the Norman camp—and sent them back off to Lombardy, as the crown couldn’t afford to keep paying them for the manhunt to come.

Cursing Thomas out of the room, he did not return as my attendants came to look for me and tend to my bandages, which is when I noticed that Edouard had entered the room. My head throbbing with the pain in my side, I said only one word to him, “Alexandre?” My wife’s messenger looked to the ground, and his expression was all too clear. Lashing out at the servants, I pushed them aside as I raised myself to my feet, and, as they called for help, I managed on a few steps towards Edouard, a horrified look on his face, before I fell to my hands and knees. I then rolled onto my side, the very same one I had been stabbed, wracked with pain as I wept—not from the wound, but for my son, who would never see the land I was saving for him. I did not moan or cry out, and, while Edouard fled the room like Thomas, the physicians arrived, and took me, wearily, back to my bed. Giving a quick inspection, he said the wound had opened, and he needed another surgery, and so, with my tears drying upon my cheeks, I didn’t say another word as he put the dowel back between my teeth.

Leaving my commanders to take care of the Normans, I returned to Melun, my side re-stitched, passing around Paris, for the dark miasma of Saturn still lingered over that once-great city. Arriving at the chateau, I spoke not a word as I hugged my Agnes, as well as Hugues and Jeanne, as my young brother and sister were my siblings as much as he had been one to Hugues. It took some time for us to speak about Alexandre, but, when we did so, Agnes said that Alexandre had been cremated, just like my Father and Mother. She had said that she would place them in Saint Denis, like the Capetians and Vexin-Amiens before us, but she didn’t dare venture near Paris. But, to that, I said that they couldn’t, as they were not Kings. Father would have to be buried in Bruges, at least, as that was his seat, but Alexandre… I pondered the thought. Where could we go? As Jeanne said that we belong at home, I was struck by a sudden thought—where was home for the de Boulogne but that city upon the sea?

It was as Agnes considered this that I had another realization that I had never been to the city of my forefathers, nor that of my wife’s lineage, Saint-Pol, as Flanders had always been well-kept by my Father. Finding some inspiration in my idea, Agnes spoke of the Basilique Notre-Dame de L’Immaculee Conception, which she said had been the burial place of the counts de Boulogne, the last one having been my great-great-grandfather, Eustache VI. Saying that we would plan a trip there in the spring, I was met by a messenger, who said that Phillipe de Valpergue had encountered a large contingent of Norman raiders within the Perche, and they had taken some castles within the county. While they were trapped for now, the levied troops would soon take their leave for the autumn harvest, and so Philippe sought royal troops to hold the Normans until they surrendered

Though I didn’t wish to spend the winter in a camp, with my wound still healing, it was still my duty to be with my troops, and so, looking forward to a trip to the Atlantic in the spring, we made our way west, passing through the famous forests of Perche, where we would have ample supplies to warm ourselves. Although I was only 29, I felt like an old man, slow in step and movement for care of my side, though I felt at ease when drinking hot, spiced Percheron calvados cider, as I had now become adjusted to the taste of Norman brandy. God be praised, the snows were late and few, and then quick to melt, and so Philippe and I felt at ease as we split our forces between the Norman-held castles. However, there was one threat we overlooked: a few days before the New Year, our men reported that they hadn’t seen any sign of the enemy in the wooden castle of Mortagne in several days. While the siege commanders had sent out scouts to see how the Normans had escaped, they hadn’t found any tracks, and the castellan of Mortagne, whom had escaped beforehand, confirmed that the only escape tunnel, which lead to a shallow point in the now-empty moat, was still blocked by icicles.

While the Normans weren’t responding to any attempts at parlay, my men wished for permission to infiltrate the castle, using the escape tunnel. I, too, was curious about what had happened to the Normans, and so I tasked Captain Jean de Loches with gathering men for such a mission. There was a cold silence as we watched the men descend into the moat, and, with no movement from the Normans, they battered away at the ice, revealing a hidden ladder beneath the castle’s walls. Watching them climb, a chill on the wind followed a gentle snowfall, and, with the ache in my side, I knew that winter’s arctic grasp had finally come. But, with men still watching the walls, I kept my own view on the castle, and awaited any signs from Jean’s expedition. We had nothing, until we saw something fall down the ladder, splattering on the rungs and the ice. This was then followed by a very shaky soldier, whose hand slipped, and he fell into whatever had dripped, but he didn’t seem to bother as he pushed himself forward, shouting “Plague! It is the plague!”

As he ran to us, we realized that the man had been covered by his own vomit, and, as the rest of Jean’s men returned bearing the same result, Jean’s eyes were hollowed as he delivered his report to Philippe and myself. While Mortagne wasn’t that big of a structure, Jean said that hundreds of the Normans had gathered within it, but none had survived—with most of the garrison having been inflicted with the plague, the remaining had turned swords upon each other, not out of malice, but as to avoid the sin of suicide. Struck by the comradery of my enemy, I asked how Jean learned of this, and he handed me several scraps of parchment, which he said had been in the hands of the Norman commander, bearing their account of what had happened, and the roll of each Norman soldier whom had been in the garrison, and I was moved to tears: they feared us so much that they chose death over surrender, all for a usurper they had never believed in. They were fools, but glorious fools, and I was impressed by them, and so I sent out riders to the other siege camps, as well as Geraud de Guines, extending royal offers of parlay to the Normans—no more brave men needed to die for a wasted cause.

Burning Mortagne down with the consecration of Bishop Hugh of Mortagne, the Normans were entombed in their ashes, and spirits were high, now that the Norman invasion had finally been put dealt with. But, not all was over—and it emerged first with Jean, in the sign of his buboes. As the man panicked, Hugh tried his best to keep calm, but every step he took away from Jean drove the captain further into despair. As the members of Jean’s expedition were isolated, I tried to prevent chaos when a black-clad Jacobin nun suddenly stepped forward, and, kneeling before Jean, a chorus of the Lord’s Prayer, and, almost unanimously, my men stopped their worry and joined in. I did too, and, by the end, we were all entranced by this old Bride of Christ, whom Hugh called Guillaumette. After giving her blessings to Jean and his men, whom were taken by Percheron draft horses to Mortagne, Guillaumette then turned to me, and spoke of the sickness upon my land, one that snared my people, and killed babes in the crib. As the whole of the land suffered from the miasma, I was weary of her words until she said that the darkness even held me in its grasp.

Disturbed by this last comment, I asked her what she meant, but the nun wouldn’t speak any further. It was then that there was a sudden pain in my side, and I clutched at my wound, which Guillaumette then demanded to see. While I was uncomfortable to expose my body to a bride of Christ, I thought back upon her previous warning, and took her word, setting up a tent for her private investigation. But, after my squire helped me with my mail, Guillaumette didn’t take a look at my wound, but traced the side to my arm, and then produced her rosary, saying that my sins had caught up to me. As she said that she would pray for France, I was angered by her as I realized the implication of her words, and so I ordered that we make for the nearest hospital, which was in Maine. Leaving the rest of our forces to disperse back to their places, we rode on ahead, Guillaumette riding on a Percheron horse, per my command, for, as much as I didn’t like her, I felt that she was necessary for whatever would arise.

However, it was too late: the next morning, the spots had already formed across my chest, and the inn house was cleared as my head burned. I was too weak to go to my horse, nor even put on my over clothes: I was dying, clear enough, and so I ordered Guillaumette to take my last rites, as the Bride of Christ was holy enough to perform the sacrament, though she wouldn’t anoint me. As Philippe had sent for a priest, I took the Eucharist for the viaticum, though a part of me feared that I had lost it during my expulsions, as I heaved nothing in the end. Making my confession to Guillaumette, as well, I took some comfort in her acceptance—except for one part, as she said there was one sin I could repent in indulgence. Swearing that our coffers weren’t sustainable for a donation to the church, Guillaumette shook her head, as she said that greed was the cost of my sin: usury. Despite my delirium, I remembered how I had made oaths with the Templar of Lens and the Jews of Bruges, and, as Guillaumette said I had harbored the enemies of Christ, which had brought the darkness upon our lands, she said that I also had the power to make it right, and remove them from our land to save our people. For my soul, my final act was to order the expulsion of the Jews from the Kingdom of France, with one of Stephen’s riders taking the script to Melun for dispersal.

As that seemed to be Guillaumette’s greatest concern, I was now able to focus on myself, as the priest had finally arrived, and so I took my private confession once more, expressing my shame in my moment of weakness, as I already regretted expelling the Jews, for I doubted my soul would be lightened by such a dark act. From Alexandria to Paris, I had found myself surrounded by a multitude of different peoples and ideas, and had not turned my back on anyone, as, I too, was an outsider to this land that I had embraced as my own. It was as I wept that the priest admitted that I still had time to change it, and, offering me a tonic of “four thieves’ vinegar,” he told me that he had seen its success in his parish. Placing my faith in the father’s words, I felt the pain lift from my body, and, soon enough, I felt nothing at all.

!King Hugues de Boulogne VII! [124]

My sister-in-law was shocked by the order that had arrived from Perche, as the expulsion of the Jewry was out of character for Guichard, a far cry from the earlier message of parlay that would hopefully end the Norman War. Refusing to issue the order, she was completely unprepared as the next rider, only an hour later, spoke of her husband’s death. As there was unrest in Melun, some eyes looked to me as I said that we should wait for proof, as, perhaps, Guichard had gotten better and the message had been sent out too early. While the rider denied this, it was the most I could do to keep Agnes calm, as both she and my older sister Jeanne had begun to weep uncontrollably.

However, it only prepared them for the reality, as a Dominican nun named Guillaumette arrived, bearing my elder brother’s urn, saying that he had died on the 7th of January. As she said that she had taken his services, I gave her access to the Couvent Saint-Jacques, though I regretted it when she mentioned my brothers’ final act. As she said that the people of France were already rallying against the traitors in our midst, she said that the best way to protect our people from further Jewish sorcery would be to enact the other. I didn’t think it seemed right, as even a 7-year-old like me knew that Jews weren’t really magical, and a part of me believed that Guillaumette had coerced it out of him. But I couldn’t argue with an old nun, at least for too long, and so, when the apostolic legate from Pope Gregorius VIII agreed with Guillaumette, my first act as King was to approve my elder brother’s final wish and expel them from my Kingdom—there would be fighting, otherwise, and more would die.

With Agnes serving as regent until I could come of age, it was now just Jeanne and I, though, since Alexandre had passed, I was now the subject of the court tutors, and so I could no longer spend my time learning about the legends of the Greeks—I was to be trained to become a Christian knight and a future king. This included lessons with the clergy, and so, as April arrived, I wasn’t able to join Agnes and Jeanne on a trip to Boulogne, as Guichard had wanted, as I instead had to attend lessons with Bishop Amaury of Chinon. Even though Agnes protested, Archbishop Barthelemi of Rheims managed to convince her it was in my best interest, and so Amaury took me to meet and Bishop Alphonse d’Artois of Evron, hauled off to Maine to learn about the church and perform some rites I would learn to embrace as God’s chosen King of France.

Kneeling with Amaury and Alphonse before a candle-lit altar, I prayed to God for vision and clarity, as the kingdom laid in ruins, its king hadn’t the funds to support it, and its peoples were divided. But, especially, I was troubled with the spiritual well being: I had learned a lot of the east from Guichard, and how different peoples were, and, especially with how Guillaumette had pursued the Jews, I found my conscience in conflict with Holy Mother church. Though I had been dismissed before for being naïve and childish, I felt my ideas had merit, that wise rulership wasn’t about using might to dismiss, but using might to reinforce that which was right, a sword only to be used when the shield could no longer withstand blows. It was in the middle of these prayers, that a voice entered my mind, one that I didn’t recognize, but I understood, as the presence of God. If there was a conversation, I would be ashamed to admit my recollection could not recover what was exchanged, as I opened my eyes as Alphonse shook me, saying that I had been shouting in French. Asking them what I had said, Amaury took a few seconds to say that I had been reciting verses from the New Testament, in perfect translation, and, asking me if I knew Latin, I confided that it was not as much as I should. As the bishops claimed it a miracle, I was curious about the verses, and so I asked them if there was a translated bible, to which the two immediately decried as improper.

It made no sense to me, as, since God had watched over me all of my life, why should I be denied the opportunity to read his word? It was another strike against the Church, but, for all my power as Roi, I couldn’t oppose the institution in Rome that had risen up and jealousy held God’s will since Paul had brought it to that city. The Pope could claim to hold power over God on earth, but He held true dominion. With that in mind, I swore before God that my mission would be to unite France, now broken and divided in the wake of the Devil’s terror, and bring the true faith back to its peoples. It was as I returned to Melun that the first sign of God’s guidance appeared, as Josseline de Toulouse had been stricken down by the Black Death, gifting the wide domain of Burgundy into the hands of his much weaker son, Geraud. But a cornered wolf bore his fangs all the sharper, and the Duke started his reign with an invasion of Bourges, against Julien de Blois. But, as I attended the discussion of how to proceed, I suggested that this was a second sign and a chance to bring Bourbon and Berry back into the fold as a display of my virtue as a liege lord, and the lords agreed. On sending emissaries to Julien, his brothers Geraud of Sancerre and Adrien of La Marche, and their rogue neighbor, Pierre de Semur, promising them protection in exchange for renewed oaths of vassalage, as France would no longer be splintered.

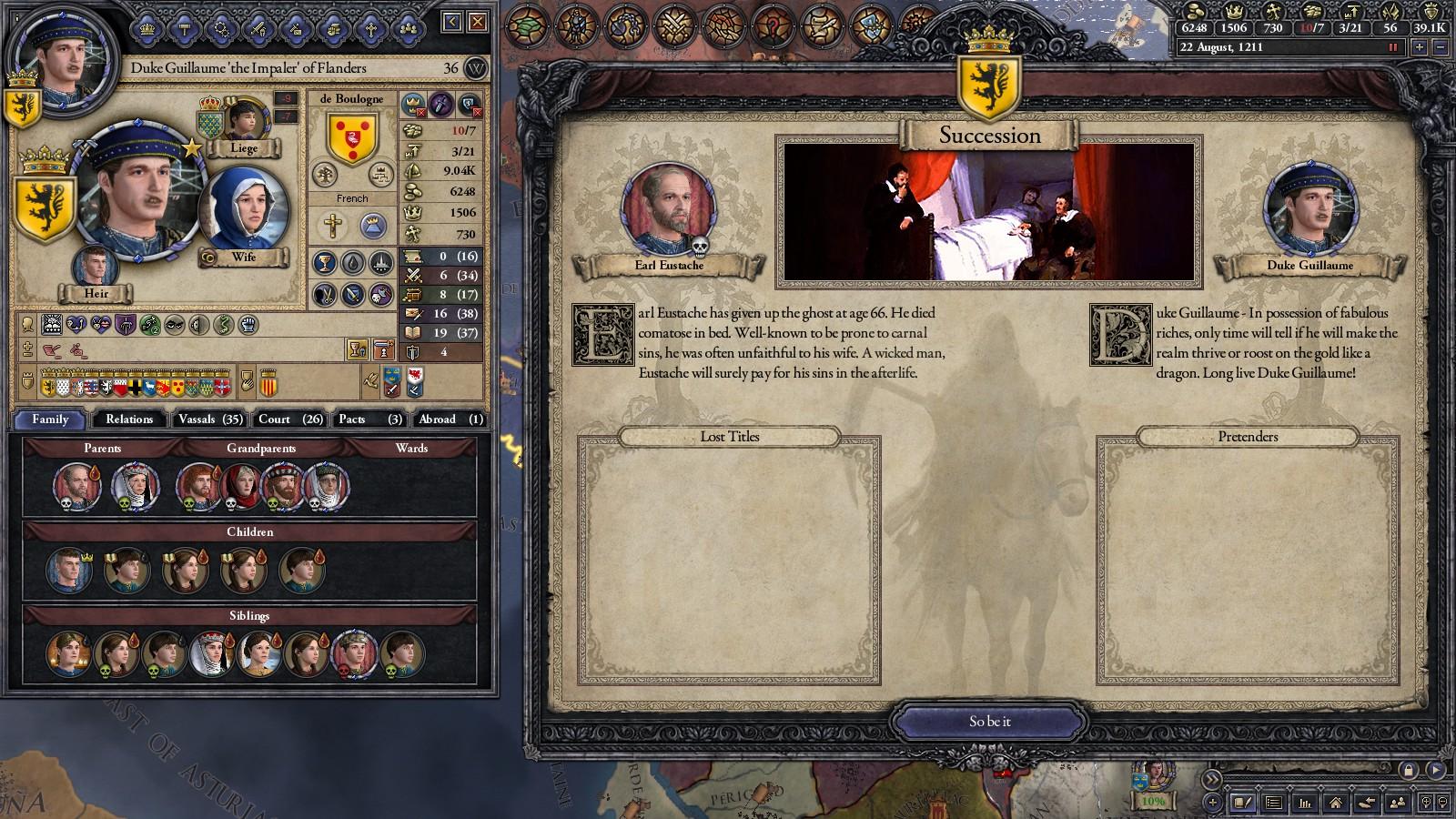

However, of the four, only Geraud de Blois accepted my offer, coming personally to Orleans as Loup Karling, son of Thomas, gathered our forces for the intervention, braving the January snow drifts as the man accepted the authority of his young king. For his humility, I made a reward of his loyalty, and dubbed him the new Duke of Berry, and telling him that his brethren had rejected my exchange. His family honor at stake, Duke Geraud was quick to say he would inspire his brothers to see the light, and, by February, both Julien and Adrien agreed to my terms—on the condition that I defeat the Duke of Burgundy. As I assured them that we would, Loup swiftly defeated Geraud’s forces, and sent the rogue Duke fleeing back to Burgundy before summer. While the de Toulouse was undaunted, my attentions were turned to my sisters, as a Moorish messenger had arrived, bearing news from the Maghreb, as my sister Isabeau’s husband, our cousin Eustache, had died overstressed, and, as the Maghreb didn’t respect the claims of her daughter Belleassez, the Kingdom had returned to my uncle Guichard. While I didn’t know much of my estranged sister, as she had left to marry before I was born, it only meant that I was much more protective of my elder sister, Jeanne, but she had reached 10, and so she was ready to depart for Cremona, as she had been betrothed to Prince Simonetto Crispo of Italy.

Saddened by her departure, the halls of Melun felt much colder without her, but, there was some good news, at least, as 1277 came to an end, as she sent back a letter saying that the Black Death had finally been lifted from the Mediterranean—surely, France would be freed as well. Pleased with that, she soon sent me all manner of books she could find, and, expanding my vocabulary of Latin, I retraced the strategies of Julius Caesar through our lands, back when it was once known as Gaul. But my readings were interrupted when a man arrived, saying that Loup had requested I join him in Burgundy. But, for that, Orson said he was a blacksmith, and so he sought to serve his king and make me a coat of mail befitting my growing size and stature. Seeing no reason to disagree with Loup’s messenger, we went to the armory to be fitted when the man suddenly flew into a rage, and started speaking to me in a language I didn’t understand! Grabbing at a nearby weapon, I hefted my great-great-great grandfather’s mace, I fended off the man as I noticed his curly hair and longer nose, realizing that Orson was a Jew. But God had protected me, and he would do so again, and the mace of Eustache V, anointed in the Second Crusade, broke through the sword that Orson had used, and struck him out.

Summoning aid, my guards hauled him away and, upon my questioning, a check of the register noted that Orson had been a goldsmith before his exile, connecting the dots as I realized that he had been intending to collect on my father’s debts. My 10th birthday then came with celebration, as Loup had defeated Geraud de Toulouse, and so Julien and Adrien de Blois returned to the French fold. Furthermore, my sister’s tidings had proven true, as reports said that the Black Death could now only be found in the most remote bogs of Flanders, and the summer had nary a dark day, as God’s triumph over Satan was revealed for all. Emboldened, I didn’t need to convince my lords that it was time to act, as they were already ready to march into Burgundy and Amiens, guided by the light of heaven, and finally bring the Duke to heel.

As I was still told I was too risky of a battlefield asset, I instead took my leave for Maine, as Count Gelduin d’Artois, a rather dour man of Karling stock, wished to teach me the finer points about the royal sport of hunting. Without any hounds, he pushed me towards hunting on my own, about using stealth and speed when it was needed most. Waiting along a small stream as the chills of November swept in amidst the leaves, I watched as a buck crept his way for a drink of water. I had some introspection about killing another creature, but I realized that God had a plan for all of us, and this creature had been called upon to fulfilling this crucial lesson. Trusting in my arrow, it dug into the deer’s vitals, and the creature died instantly, much to my surprise, toppling besides the stream. As I had expected to fail and chase it, I had been given a short spear, but it appeared it wasn’t needed, and so I called out for Gelduin, as he said that he would help me prepare and carry the creature. However, as I turned around, it wasn’t the Count of Maine, but a bear! As we glared at each other, I tried to make myself as large as possible, making sounds and raising my shoulders, but this only made the bear roar and charge at me. At this moment, I found myself considering several options, but I acted on one: dropping my bow, I retrieved my spear and jammed it into the ground, using it as a low point to thrust it into the bear’s neck. Just like the deer, the bear was caught in my strike and, as I pulled the blade across its throat, the beast toppled over, lying beside the other creature. It was then that Gelduin arrived, saying I was making too much noise, but was stunned by what I had done. Calling his servants, they gathered the bodies for preparation as I was inspected for injury, but, untouched, we both thanked God for the miracle.

As I returned to Melun with a bearskin rug to warm the foot of my bed, I was informed of the status of the war against Duke Geraud, as Duke Julien d’Ivrea of Troyes had tried to seize upon the war in Burgundy to claim the county of Dijon. And then, Duke Geraud had managed an alliance with King Jacopo di Tortolì of Sardinia, having married his sister, Camilla, but it was of little matter, as our alliance with the Italians held a strong deterrent. However, there was another issue in France, as well as the rest of the world, as, now that that the Black Death had faded, the shortage of labor had driven rents down in the countryside, attempting to attract freemen with promises of larger self-owned plots, whilst the guilds increased wages to retain their artisans. These new tenured freemen had soon come to become landowners themselves, and with manumission expanding their number, many came into conflict with their former masters. Knights were quick to defend themselves against the growing peasantry, but relations spiraled out of control, as the support of the guilds led to the well-off commoners coming into arms and armor.

We heard tales across the land of these battles, particularly in Britain and the Holy Roman Empire, though the latter also came with news of the Crusade: despite having been announced nearly 8 years ago, the war was still ongoing, as the Germans had preached it as the salvation from the Death. Kaiser Maslaw Premyslid, the King of Hesse, had led in this effort, and was said to still be fighting the Persians in al-Jazira, over the graves of my father and Emperor Beuves. In the meanwhile, I received a Christmas gift from our immediate east, in the form of Duke Geraud de Toulouse in chains. As his forces had been defeated at the battle of Gien, he had been routed and captured at Perrecy just a few days later, and so 1279 came to a close with Burgundy and Amiens returning to the fold.

Releasing him upon ensuring his contract was signed, I made sure to keep a close eye on him as we let the land mend for 1280. However, there was an unexpected arrival in Melun, as I came back from another hunt with Gelduin to learn that Prince Simonetto of Italy had been killed by the people of Milan, and, rather than withhold her in Cremona, Jeanne had come home. Though I was gladdened to have my favorite sister back, Agnes immediately started looking for a suitable husband, as marriage was the only thing I could not sway her mind on. Thus, Jeanne and I only had one more summer together before she departed for the Imperial Capital of Marburg, where she would transition from Italian to German for her new Prince, Amadeus Premyslid, cousin of Kaiser Maslaw. I hoped that it would be well for her, as she was a patient girl, though I’m not sure if her previous betrothed’s murder was good for her mind.

However, the New Year’s celebrations were soon followed by the tolling of church bells, as we learned that Jeanne’s life would be anything but humble, as the Kaiser had taken Mosul, and, with it, the Assyria and the Nineveh Plains. The Turks had fallen back, and the Crusade had been victorious, coming at the cost of hundreds of thousands of valorous knights and champions of Christendom. And, for his victory, Pope Gregorius VIII had given Kaiser Maslaw permission to divvy up the lands as he had seen fit. But, with the German Reich stretching from the foot of Italy to the eastern reaches of the Baltic Sea, the Kaiser had declined the honor, and had, instead, named his cousin its new King: Amadeus would rule al-Jazira, and Jeanne would be his queen. As a number of those descended from those who had followed my father to their deaths descended upon Marburg to press their claim tokens of land for what their fathers had died for, I received a personal letter from the Kaiser, who had only learned of Amadeus’ betrothal to my sister. Within it, the Premyslid swore that, as he would ensure his young cousin would become the proper heir to such a historic land, he promised that Amadeus would protect Jeanne as much as his new kingdom.

Honored to receive the Kaiser’s assurance, I could rest knowing that Jeanne would be kept well, as she had been writing only the praises of her betrothed. While the spring of 1281 arrived, I had no time to rest, as I had finally found a way to secure Bourbon from Pierre de Semur, as none of the de Blois brothers could convince the man that he should return to Frankish authority. Turning to steel, I ordered Duke Geraud of Berry to lead his brothers against the man and press the claim of their mother, Eustache de Semur, Peire’s sister. Swearing her vassalage upon her recognition by the bishop of Gueret, I sought to continue our momentum against the weakened state of Occitania, but, as we sent an ultimatum to King Archambaut, news erupted of a large peasant uprising in England. Disgruntled with how the Emperor of the Britons had refused to adapt to the aftermath of the Black Death, the people of London had scared Henry, the second son of Emperor Inwaer, out of the Tower, proclaiming an independent, royal city.

While this bid poor news for that of the Emperor, we feared how this news would travel, given the recent strife, when we learned that a bailiff in Chalons had been murdered whilst trying to settle a dispute between a wealthy champagne merchant and an offended knight. While the knight had retreated chateau, the merchant had rallied thousands of commonfolk against his foe, and, after killing the man and ravaging his property, the horde started rampaging across the land, stealing and burning whatever noblemen they could find, absorbing more into their ranks. Fearing another London, my levies were ordered home to ensure Paris’ cooperation, dispatching the Flemings against the Viticulturist army, as it was now called. Luckily, Geraude de Guines’ knights crushed them at Le Charmel, and, as the upstart villeins were shown no mercy, Loup Karling reported that they had taken Lusignon from the Occitans, and, as King Archambaut had been displaced from Armagnac by his own peasant rebellion, he saw no reason continue that war.

As the summer ended with French victories, I had been preparing for war in my own ways, as the noble pages of France had gathered in Maine under the watchful eyes of Cound Gelduin for our own sort of tournament, competing against boys our age and skill in preparation for when we would embark upon the battlefield. It was good for me, since I had been without much company of my own age, 13 years, and talking to them all, I found myself becoming friends with all of them, or at least expected. Gelduin was surprised to see everyone stand up for me, as he pushed that, even as King, I deserved no special privileges in training, but the others were eager to help and do things in my stead. As such, we endured the punishments together and shared the load: we would all train and fight together. Of this cohort, three particulars rose to the forefront, Baron Biktor of Montfort-l’Amaury, a strong warrior, Conte Arnault of Macon, an honest friend, and Gestin Leon of Blois, a base-born, but pious, son of Count Getin of Blois.

When our time came to an end, I was saddened to depart from all of my new friends, but I reminded myself that it was only temporary, and there would be many more events that I could host to see them all again. But then, Bikor, Arnault, and Gestin all volunteered to join me in Paris, saying that there’s no way we could be separated: the Quatre Amis, and we would rule the world. Laughing, I sent messengers to their family as we arrived in Paris, and the streets of the city became our new playgrounds, as we explored and learned of the people for whom we would defend. It was from our adventures that I ran into the Bishop of Saint Denis, Ogier, and an emissary of Papa Gregorius VIII. Speaking to me of my duty as Roi, Ogier informed me that the Church of France had long acted against the will of the Holy See, and had resisted Papal Authority with Free Investiture, placing secular control over the appointment of bishops. While I had my own thoughts about the Church and its behaviors, I was too young and too powerless in my current state, so biting my tongue, I accepted his word.

While that hung upon me, the winter passed with my friends, building snow forts to learn the better part about fortifications and where to build them, tossing snowballs as we trained our throwing arms. The spring of 1282 came as we were eager to go back to our usual sports, but there was a matter that took me away from my training and play: the matter of Britain. As, since Emperor Henry had been ousted from London, the shatter façade in his lands cracked, as the Emperor of the Britons was merely a figurehead in Oxford, ruling over lands he barely controlled. This was no more evident as Adam II, Overlord of England and Ireland, had rallied his forces against his Emperor in a coup to place Margaret de Normandie, granddaughter of the old Empress Aibinn, upon the throne in… Ireland, now, for Kildare was one of the few counties the Dall dynasty had to their name. While Henry was almost hilariously outmanned, I was struck by the sudden idea of taking advantage of the British civil war to reclaim Normandy from Gaela de Gael, like Guichard had done many years ago!

With all of Adam, Margaret, and Henry’s forces concerned in the isles, the taming of the Normans would be an easy task for my forces, and, serving under Gelduin, Philippe, Geraude de Guines and Geraud de Blois and his brothers, Biktor, Arnault, Gestin and I had our first taste of the campaign, riding and serving our lords. We learned and experienced the horrors and the glories of battles, the grinding of sieges and the relief of victory, of wine and gold and women. Well, I didn’t share in the latter, as I told myself that a King needed better than creating bastards, and so my friends joined me in singing and drinking until our nights fell away. Of the whole campaign, the most unusual event happened at Evreux, as I called out our demands to the garrison, as an armored man rode out. Asking on whose authority I acted on, I told him my name, and he smiled, before dismounting. Saying that his father, Simon, had been good friends with my father, he bowed before me and accepted his place as a vassal of the French king.

Glad to have made a new friend, he invited us into his manor for dinner, and so we obliged. While learning of the fate of my father, he exchanged his sympathies, saying that his father had died while on crusade with Guriant and Beuves. As we talked with each other more, and I learned about Norman ciders, I decided that Simon was a great man, and, thus, would be the correct choice to be the Duke of Normandy. While I enjoyed the good company, some of the others were not as eager to trust the Norman, and, while they returned to their camps, I was one of the last to leave. Walking with Biktor through the streets, we were paused when we spied a strange man walking alone in the road, wrapping in robes and a head wrap, bearing a large satchel upon his back and a long blade at his hip. Calling out to him in good curiosity, the man responded with words I couldn’t understand, but then prostrated himself, saying that he had been looking for us. Not understanding, the one-eyed man told us he was a Saracen that my father had saved while on crusade, Abdul-Hazm, and wanted to pay back the debt he had owed. Thus, he offered Biktor his sword, and to me, a tome: Virtute Animi, which was just the translation of Courage.

Saying that it would teach me how to lead and inspire others (though I already found that easy enough to do), the old Saracen told me he could transcribe it properly for our records. But, to that, I said he had no need to transcribe it—he could stay with us in Melun, and live with us, if he so chose to. Saying that the stars had guided him to find me here, he accepted my invitation, and, while my lords were distrustful of the Saracen, Biktor, Arnault, Gestin, and I held our guard with our new tutor, who shared knowledge and practical skills with us, as the man had once been a famed duelist in Assyria before he had turned his hand to the quill and mind to the sky.

Studying the book, our campaign was won in the October of 1283, as the newly crowned Empress Margaret of the Britons, who stylized herself as a Welsh “Ymerodres,” didn’t care for the matters on the continent—but, that arrogance would be her undoing. Hearing of uprisings in Scotland, I realized that now would be the best time to check the British power, in the wake of their civil war, by establishing the stability and strength of the Scottish. To ensure this, I decided that the best way should also be for the best of France: although the de Vexin-Amiens had maintained strong relations through their inheritance of Gowrie, we needed to directly insert ourselves as the suzerain of Scotland. Thus, we sent our terms to the regent of the young King Malcon de Rhosan Meirchnant V, granting autonomy within his lands and aid in return for a portion of his incomes and levies towards service—a contract that was, surprisingly, immediately accepted, as it appeared that the highland clans had descended upon Strathearn en masse, as their hills had protected them from the wrath of the Black Death, and looked to be in a position to overthrow Malcon’s reign.

As we prepared ourselves for an expedition to that wet and gray island, I celebrated my 16th birthday, coming of age on the 20th of April, 1284. Holding a celebration as much for me as it was for our impending campaign, I was with Gestin when he introduced me to his sister, Solene. Another base-born child of Count Gestin de Blois, she was taller than most of her sex, standing the same as her brother, with long brown hair and kind eyes. With a joy for mischief as much as her brother, she joined us, Biktor, and Arnault as we continued with our merriment. While I danced with Agnes, the young duchess Elodie de Valpergue of Poitou, four years my junior, and Countess Alienor de Bissy of Sens, I found myself with Solene every other song. I could feel the warmth through her gloves, and, for once, I wasn’t sure what to do as we continued through the night. Though she was five years older than me, I still was able to hold myself as we bid each other goodnight with a chaste kiss on the cheek.

Saving my coronation for my return from Scotland, we made for Calais, waiting there as our forces gathered. Meeting with Mayor Leonard to coordinate supplies housing for my Flemings, my vassal was very supportive of all I said, and as the other lords arrived, they were received just as warmly, and we were all soon drinking wines supplied by the Hanseatic merchants. Satisfied that our army was ready to board the next morning, as Leonard had complimented the red sky that night, I returned to the royal apartment that the mayor had provided for me when I spied Gestin and Solene, as the two had tarried in Paris. But Gestin had a dour look on his face, and, in my inebriation, I asked him his matter, but he struggled to find the words until Solene burst out with the truth, saying that Gestin wouldn’t be joining our campaign. Welcoming them into my lodgings, Gestin revealed the truth that, while he would follow me to the end, his father had not thought the same for him, and so the Count of Blois had enlisted his bastard son with the Knights of Calatrava. Equating them with the Templars that held several domains within France, I knew that they often found themselves in more temporal problems than that of spiritual, but I said that it was an honorable life to serve in the holy order, and Gestin admitted the same, as my pious friend had always wanted to serve God. But, now he came to me, feeling guilty that he was forced to choose between our friendship and the Almighty, but I said that I wasn’t mad with him and I encouraged him to write to me. Thankful to have such a kind and accepting friend, Gestin was eased to have relieved his burden, and so I offered him a bottle of champagne, gifted to me by Leonard. Exhausted, my friend was quick to fall asleep, and, as Solene and I deposited him in one of the rooms I had to offer, it was now just the two of us. With the warmth of champagne on her breath, Solene took this opportunity to wish me good luck for the upcoming campaign, and asked when I would return. Saying that it wouldn’t be any longer than a month or two, she hugged me tightly, and told me she wished it wouldn’t have to be that long. From such close contact, we could no longer keep ourselves to chastity, our passions inflamed, and we drank champagne from each others mouths.

I wasn’t eager to depart in the morning, but, waving my farewell to Gestin, whose ship was sailing for Spain, whilst Solene readied her horse for Blois, I was forced to turn my sights north, departing for Scotland, eventually landing near Fife, where I finally had my chance to lead. Speaking with King Malcon’s regent, Fingal Cameron III, he told us that the highlanders had been last seen crossing Stirling Bridge, storming on a warpath for Edinburgh, intending to seize power for themselves. Thus, crossing the Firth of Forth, we landed for Borrowstounness, and continued west along the road until we arrived at Falkirk. Marching our battles along the Callendar wood, our forward scouts reported that he had seen the highlanders, and, undetected, said they were on the other side. Claiming them to mostly be clansmen armed with pikes and swords, we readied our cavaliers and crossbows for the coming maneuvers. Unknowing if they knew King Malcon had submitted to me, I asked the Scottish hobelars to pull them around the forest, as I gave command to Fingal to make the appearance that the Scotch army had arrived. Doing so, he arranged himself before the city and the highlanders took the bait, charging without consideration for their placement when we emerged from the forest, a volley of bolts tearing into their side. As they turned to face us, Biktor led the cavaliers as Fingal county charged with our footmen. Caught in-between, the highlanders were slaughtered, their chieftains were captured to be hanged, and the rest were allowed to flee back towards the hills, a mercy as we made our point to our new Scottish allies.

Of course, that was only the first to come—as our return to Edinburgh intercepted us with a British Emissary, speaking of demands from the Ymerodres of the Britons, as Margaret, now based out of Oxford, demanded the subjugation of the Scots. For the Normans had held Scotland for some time, taken by Emperor Aubrey de Normandie II in 1200, but they had lost control when Giric de Rhosan Meirchnant, ironically of the same highland stock that we had just slaughtered, seized advantage of a civil war between Sara and Lionel de Normandie to reclaim his kingdom’s independence back in 1228. Claiming that Briton referred to lordship over the whole island of Britain, no doubt the wordplay of King Adam, Margaret demanded obedience from our suzerain, to which I gave Malcon a chance to respond: “No!”

Fearing the numbers that they could muster, I summoned the whole of the French army for Scotland, defending our interests and prestige, for Britain would be our first step towards French reclamation. As I received reports of my army’s mustering back in Calais, the English were already on our doorstep, as they had been rallying in Strathclyde, the land of Laurence de Normandie, whilst we had been concerned with the highlander host. Forced into the defensive, I looked to Fingal on how to defend his land, to which he recommended what he called the most familiar of Scottish strategies: hold the highlands. Though I doubted any of the clansmen would join us after what we had inflicted upon them, I was surprised to see tartans and flags emblazoned with Saint Andrew’s cross standing along Loch Faskally, as the “heelandman” wouldn’t let their country fall to foreign invasion. Glad that my presence was already welcome as a defender of Scotland, they had gathered at Pitlochry, blocking the roads to Blair Atholl.

While the clansmen gathered, raising our numbers to 10 thousand, the cool winds of September pelted our tents as the hobelars reported the first sightings of the English host, 15 thousand strong. With the terrain limited, I knew this would be slow slog of a battle, and I ordered my knights dismount as we made our way to the land we had prepared: French crossbowmen and Scottish bowmen taking position upon the hills as Scottish pikes formed schiltrons, their gaps filled with French men-at-arms. With one side protected by the River Tummel, we made our stand, pleased to learn that the British hadn’t been burning the countryside, as they intended to unify the lands, not punish their intended vassals. When they finally arrived, I expected to see the banner of the King of England in their number, but there was only the Dragon of Prydain; the message was clear: this was Margaret’s army, and Margaret’s alone.

Then, her banner rode forward, and, after Fingal got agreement from his young king, the Scots and I sent out our riders, intending to see what terms were offered, as custom dictated. But, of course, there was nothing of worth from the British, as the Ymerodres demanded full annexation, having advanced from her previous claims of subjugation. Laughing it off with the Scotsmen, we told the English to do their best, and so we returned to our camps and made ready. However, with our position to the advantage, the English didn’t press the attack, as the next week was for maneuvers and pronging dives against our fortifications. While there were some doubts that they were stalling for time, intending to come around the mountains, I reminded Fingal and the others that the French army was on its own way, and, no doubt, was gathering in Gowrie right now.

A second, cold week passed in Pitlochry, and the thought struck me that they might be intending to stick out the skirmish, as the range of their Welsh longbowmen put them at even odds with our raised crossbowmen. And, while Sweeny Macc Finnagain and Henry Mac in Rothaich suggested we take the advance, I doubted that their enthusiasm could match English men at arms one-for-one, which didn’t fare well for our odds. October and the Scotsmen grew ever dour, as our supplies had dwindled, and there was only so much Scottish drink I could stand. We wouldn’t be able to engage in this kind of siege for long, with the English controlling the more fertile lowlands, and, already, some of the clansmen had started dispersing. All hope seemed against us, until a rider came from Blair Atholl, speaking French: saying he spoke for the Baron of Confolens, Davi, the French army was ready and was marshalling against the English rear.

Ordering them to attack first to stir up confusion, we would follow, charging down the hill, over our fortifications. Given two days to prepare, morning broke in the east, and the English had begun to move forward, noticing how many men we had pulled from the earthen ramparts. But that was a part of our ruse, and it was then that we saw the flag of Confolens rise from the eastern hills signaling the attack. A grand horde of knights rippled out from the lowlands, driving through the British camp, and, as we launched forward from our positions, it took no less than half an hour for the Dragon of Prydain to fly south! Taking a quick count, we had killed a third of the British host, while our forces, with the reinforcement of 10 thousand Frenchmen, had only lost 1 thousand during the fight.

While a number of Scotts took to looting the camp, I finally met with and greeted Davi, thanking him for his service and, rather preemptively, for winning the campaign. A humble man, he thought nothing of it, and so we followed the English south, harrying them at every opportunity, assisted by Scottish hobelars the whole way. They tried to assemble at Lanerc, under the Dragon banner, and, despite how half of our battles had lagged behind, we engaged, bringing a thousand more than they. With the Scottsmen surrounding on the flanks, we took the van, smashing through the disheartened English as they sought survival, more than any conquest. And, as we rode through the ruined lines, I saw the Dragon banner had fallen, and, cheering with the hobelars, I stopped when I saw what had happened. A number of Scotsmen had surrounded the Ymerodres, and, having cut down her standard bearer, a laughing clansman had run her through with a two-handed sword. Having pierced right through her breast, I was shocked to see such brutality levied against a noblewoman, and an Ymerodres, nonetheless, but I noticed that, while she had been taken to God’s graces, she had managed to stab her assailant in the face, and so the two had died, hands still locked onto their blades.

Sickened, I demanded they relinquish her, and, as Arnault had to restrain me from striking them down, Biktor sought out the nearest nunnery, for the Ymerodres’ body couldn’t be delivered by any other means. The winter in Gowrie was a cold one, as King Adam II, acting regent for Margaret’s one year old son, Argad Menteith, sent an official declaration of peace, offering payment to myself and Malcon in exchange for Margaret’s body. By then Ymerodres’ corpse had been made presentable, and so I sent it back, alongside the English gold, expressing my regrets as the Souverain of Scotland, to her husband, Duke Cydrych of Powys. With the British defeated and spring’s fairer weather, we departed from our tributary state, returning to France, though I still had a rather bitter taste in my mouth as I was welcomed back in my Calais apartment by Solene.