Chapter 1: Werner Gets Hungry for Hungary

Our story begins in the quiet Swiss province of Basel. Count Werner von Habsburg rules a little fief next to that of his brother-in-law, Count Ulrich von Lenzburg of Bern. Werner is a tough soldier, patient, diligent, gregarious, and…content. Well, maybe he’s content with his lands, but Werner seeks to leave the next generation of Habsburgs with more than he alone can give.

Fortunately, the Kingdom of Hungary is in regency for their newly-teenage king, Árpád Salamon, and Werner has two children, Otto and Ida, with which to forge the alliances necessary to take Salamon’s throne for a more worthy candidate.

Hungary has a virtual buffet of attractive, young, and hopefully fertile princesses. There’s only one hiccup in Werner’s plan: he’s already married to a lowborn woman named Reginlind, and even if the Pope cared about a backwater count in Switzerland, Reginlind has given no cause for His Holiness to grant Werner a divorce.

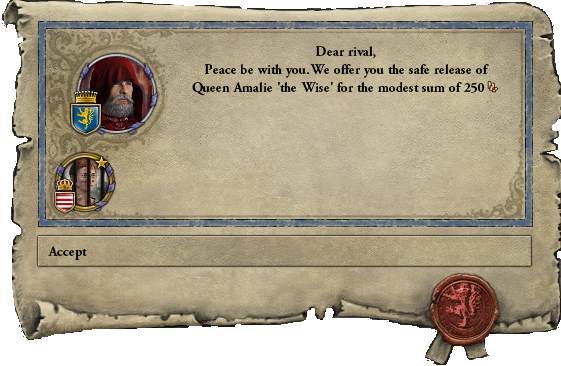

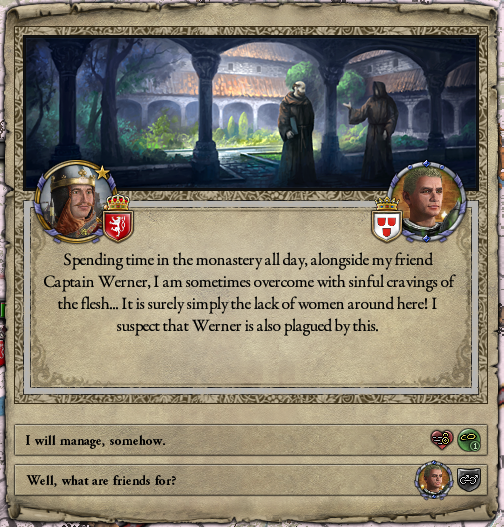

However, the one benefit of marrying a commoner is that no one cares about her life, so Werner hardens his heart and orders Reginlind imprisoned and then hanged, her neck breaking to match her heart. To ease his troubled mind, Werner begins a pilgrimage to Rome. Scholars would wonder for years why Werner didn’t spare Reginlind and order her to join a convent once she was at his mercy in the dungeons, and their colleagues would point to Werner’s low learning skill and to a particularly incompetent advisor who went straight to the prisoner screen instead of the targeted decisions menu.

Returned from Rome with what Reginlind would almost certainly consider an ironic newfound appreciation for charity, Werner begins planning his second marriage. His new bride is the 17-year-old Princess Árpád Mária, a woman with a head for sums and money, although her self-restraint meant she sometimes passed the most lucrative opportunities.

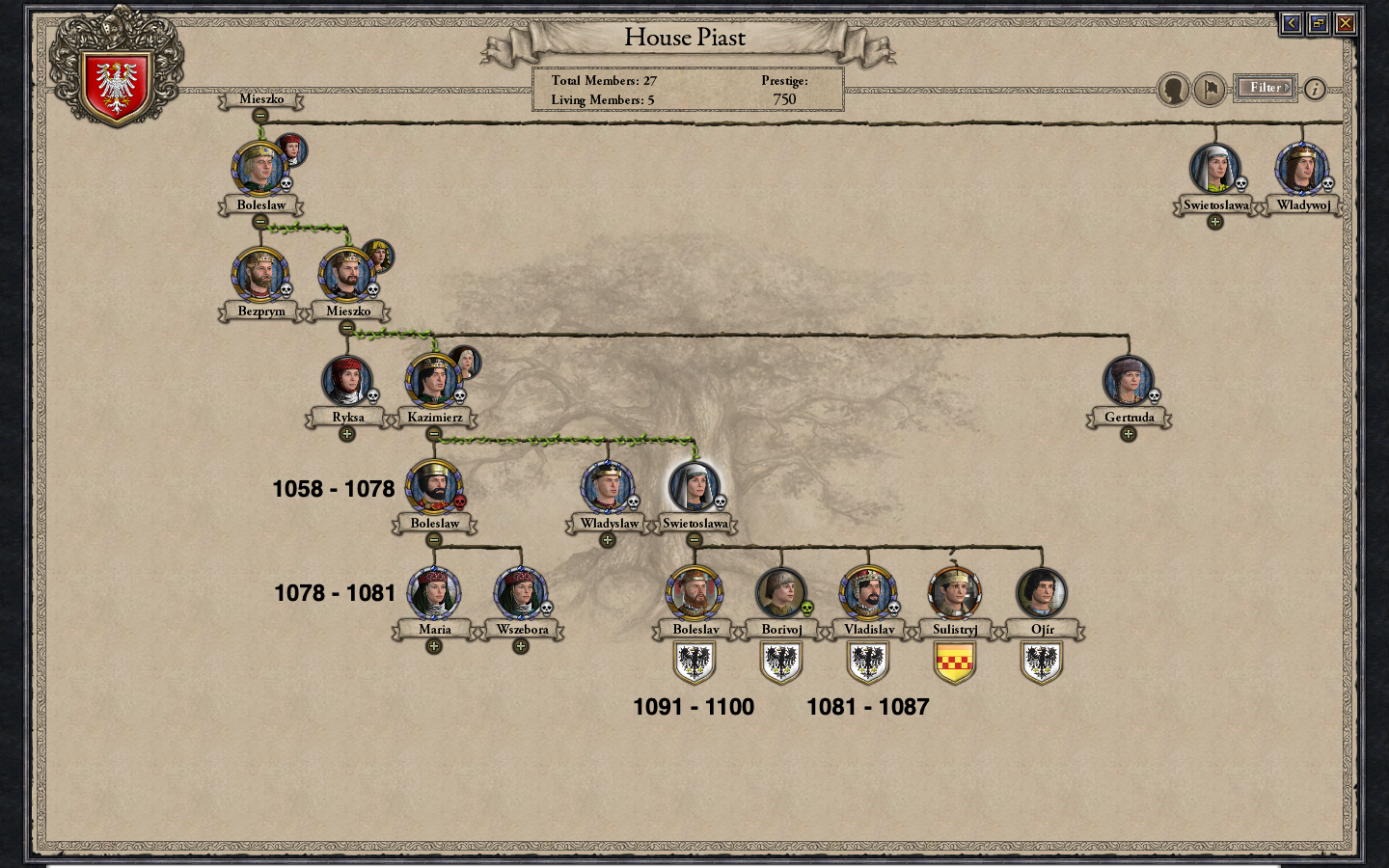

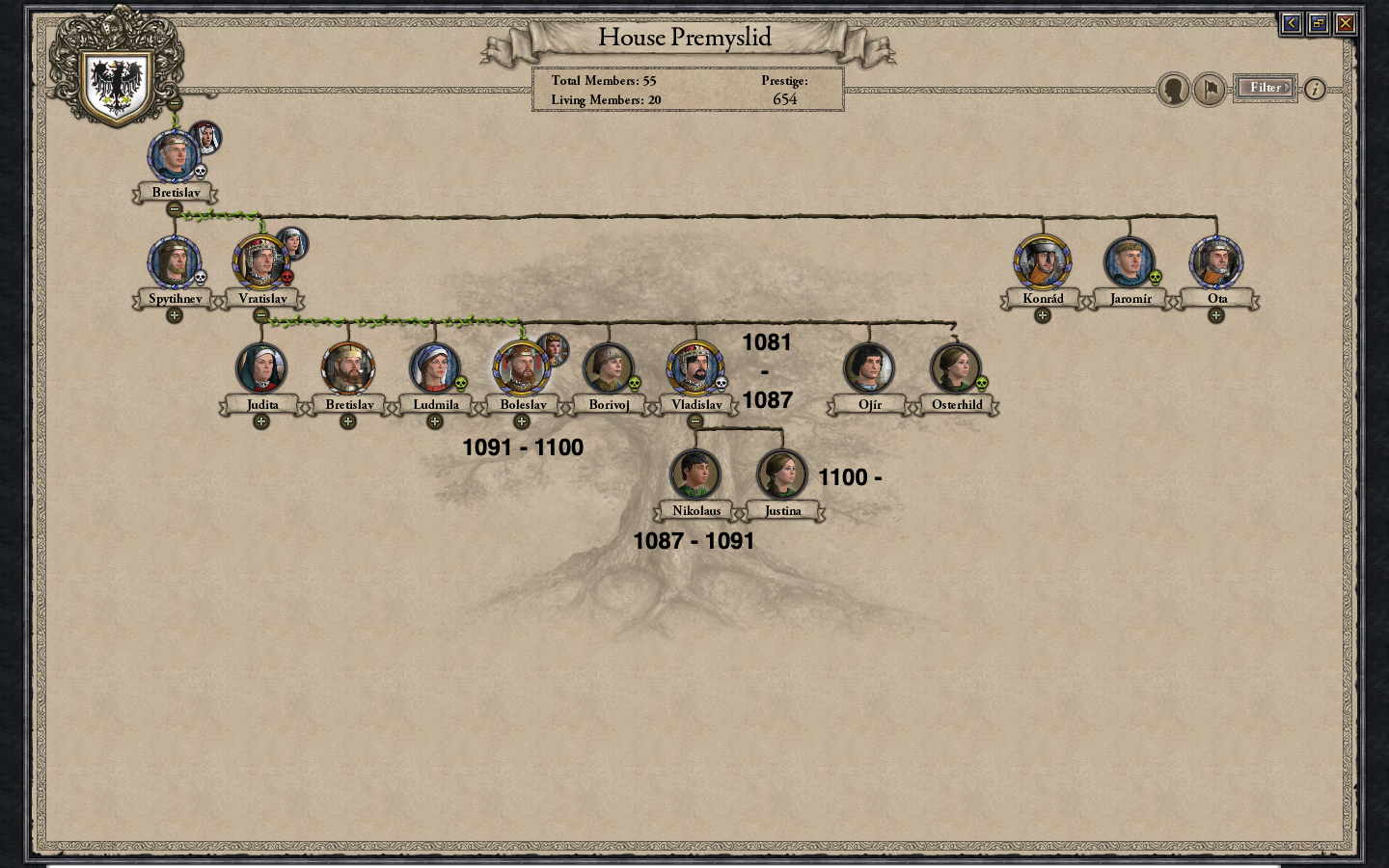

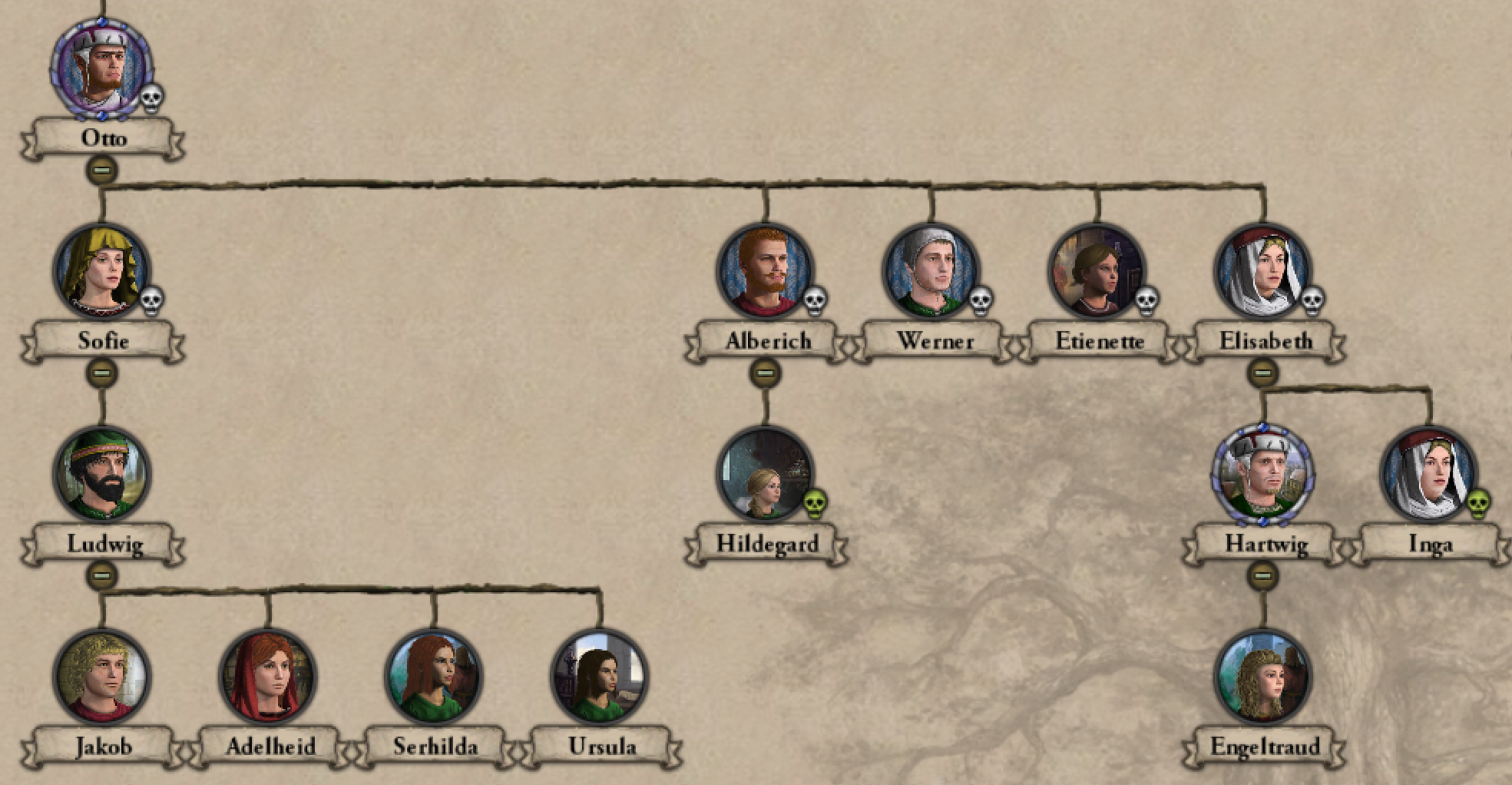

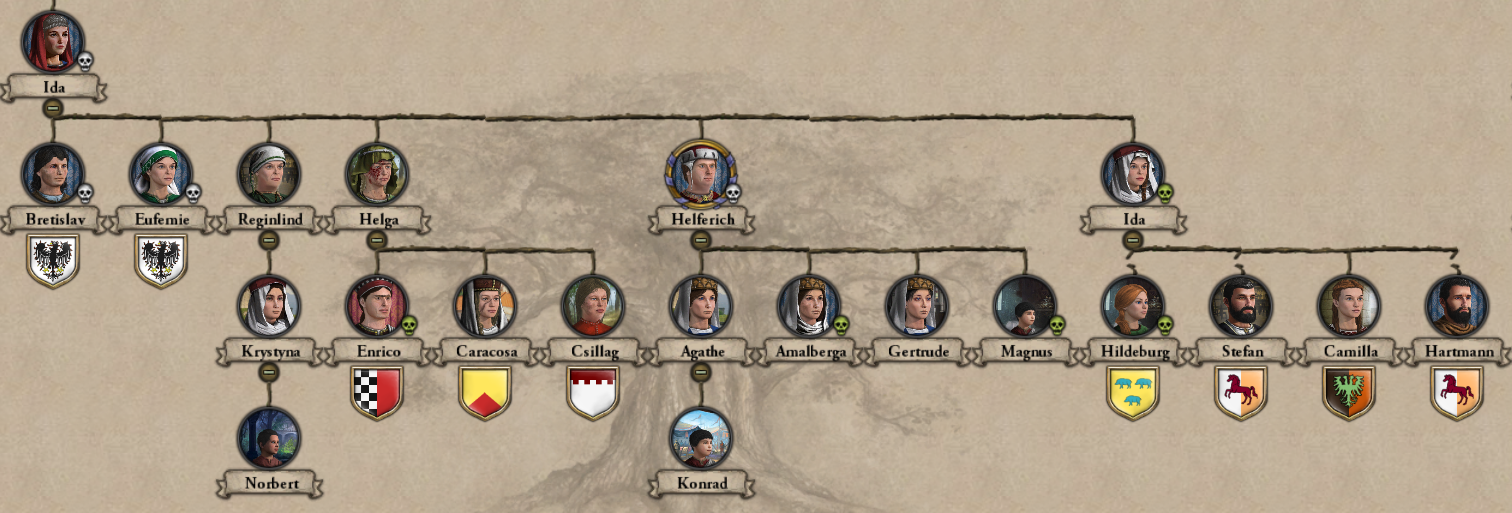

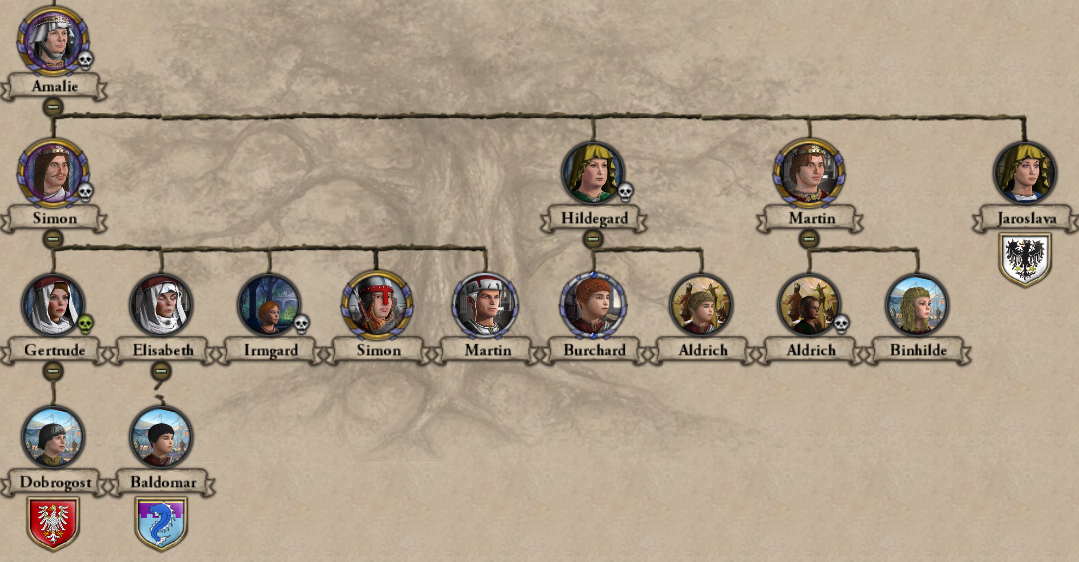

While on pilgrimage, Werner had written back to his regent, Bishop Simon of St-Ursanne, to arrange the betrothals for his children. Ida’s hand was promised to Prince Bretislav Premyslid of Bohemia, eldest son of Duke Vladislav. With this pact Werner gained the backing of the second-largest military force in the empire: 3,400 levy troops and counting. However the Bohemians would be a belated reinforcement should an enemy attack close to home, so Otto, the heir, was matched with Gisele d’Ivrea, third daughter and sixth child in total of Duke Guillaume of the neighboring realm of Franche-Comté. For extra insurance Werner got a written agreement of mutual defense signed by his brother-in-law in Bern.

With these three pacts, Werner now has access to an army six times that which he could have raised on his own. And none too soon, for King Árpád Salamon is drawing near the age of majority and his coronation within the next two years. After that day, his reign will be too legitimate in the eyes of Werner’s new allies, and he will not be able to call them to depose Salamon in favor of his cousin, the new Baroness of Habsburg.

And so, on 21 February, 1067, the fourteen-year-old King of Hungary receives a sealed scroll of cheap parchment informing him that a minor Swiss count is declaring war to press his cousin Mária’s claim to his throne. Salamon promptly snorts with laughter and asks his regent, the Queen Mother Anastasia of Rus, if she was trying to audition for the title of court jester. His mother replies sternly that this is a legitimate diplomatic missive and reads a second letter from the Duke of Bohemia. Salamon’s laughter cuts off abruptly, and within the hour messengers are on their way to every corner of the Carpathian Basin, calling all loyal sons of Hungary to war.

Salamon’s forces manage to win an early victory at Esztergom against Count Werner himself in 1068, but the Lord of Basel regroups his coalition’s forces and leads them to a victorious rematch at the Second Battle of Esztergom in January of the next year.

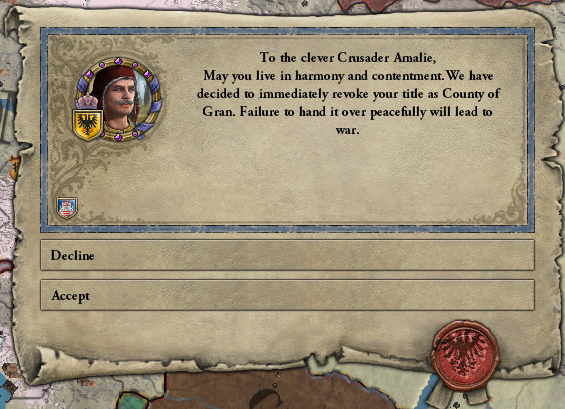

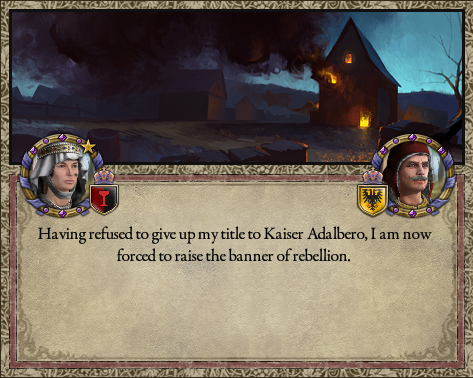

In February of 1069, while the Habsburg forces are in the process of laying siege to the Hungarian capital of Esztergom, Werner realizes one ally hasn’t yet appeared: the Duke of Franche-Comté. Werner soon discovers why: the treaty of alliance he had meant to send for the Duke’s signature had been left on his desk at Habsburg Castle! One swift horse and one beheaded advisor later (rumored to be the same dullard who had “conveniently” forgotten about the existence of nunneries during the Reginlind debacle) and Duke Guillaume’s banners are crossing the Danube to aid in the capture of King Salamon’s personal holdings.

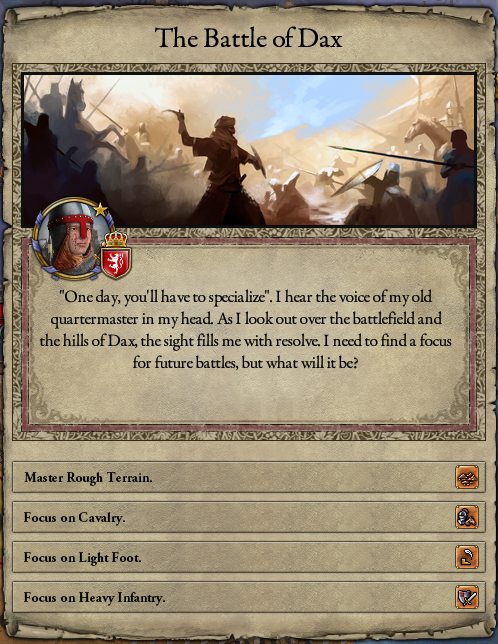

A third and final battle of Esztergom takes place when the coalition arrives to break a siege against their garrison by King Salamon’s main army, desperate to reclaim the capital. Werner distinguishes himself as a specialist in the skilled deployment of heavily-armored infantrymen, while the king distinguishes himself by losing his right eye in a battlefield duel. Unfortunately for posterity, so many of the allied commanders claimed to be the man who took the king’s eye (some even brandishing macabre trophies ostensibly from the royal head) that the true identity of Salamon’s opponent that day has been lost to history. Salamon himself, rather than offer up any useful information, would instead offer up a jest when asked if he had any idea: “How should I know? He came at me from the right!”

By May of 1070, even the now half-blind Salamon can see the writing on the wall. On the morning of the 15th, he walks into the throne room of Komárom Castle in Esztergom, dressed in full regal attire. He sits on the throne as a board is laid on his lap, a roll of parchment rolled out on it, and a quill placed in his hand. The young king reads the proclamation in Magyar, his voice stirring the audience with its combination of honesty and righteous indignation towards his enemies. Then he signs his name, presses his royal seal in wax next to it, and hands the parchment to the court chamberlain. The board is taken away, Salamon rises, and his court kneels before him one final time as he turns and lays his scepter, his robe, and finally his crown on the throne. Retaking the parchment from his chamberlain, he walks silently to the front steps of the palace, where Mária and her shabbily-dressed husband are waiting. The normally talkative Salamon says not a single word to his cousin, any remaining familial love for Mária buried deep behind an icy stare, as he hands her the official notice of his abdication. He passes by Werner on his right, so as to avoid even the pretense of a glance to acknowledge the count's existence, and begins the journey to his new seat in Sopron, trying not to hear the crowd behind him chanting, “Long live Queen Mária!”

Edited on 2020.5.18 from original to fix typos and inconsistent tense.

Edited on 2020.5.21 to correct Bohemian troop counts, which I had somehow doubled in my head.

Next Time...

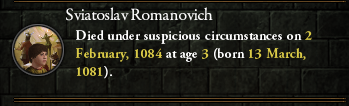

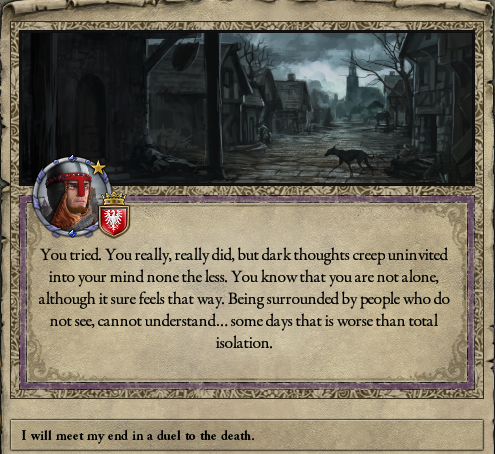

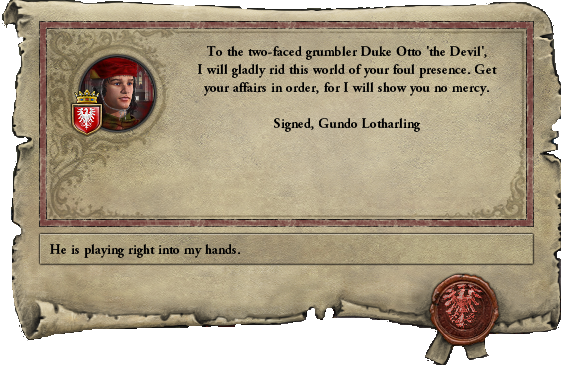

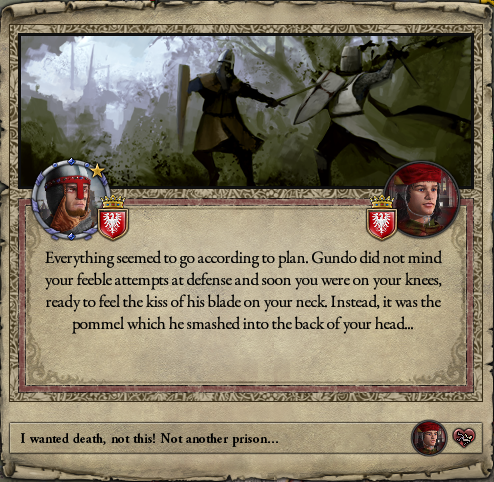

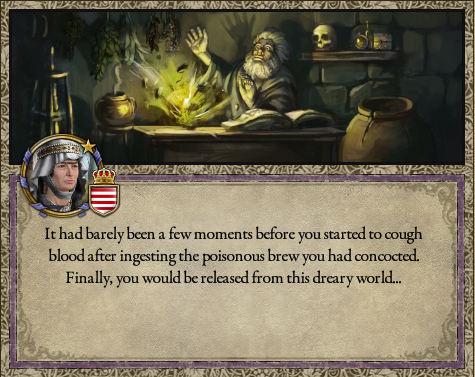

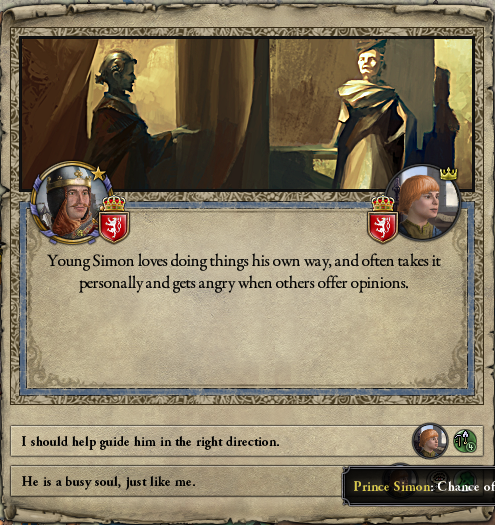

Count Werner receives tidings both good and ill, and young Otto begins to walk a path of darkness...

Our story begins in the quiet Swiss province of Basel. Count Werner von Habsburg rules a little fief next to that of his brother-in-law, Count Ulrich von Lenzburg of Bern. Werner is a tough soldier, patient, diligent, gregarious, and…content. Well, maybe he’s content with his lands, but Werner seeks to leave the next generation of Habsburgs with more than he alone can give.

Fortunately, the Kingdom of Hungary is in regency for their newly-teenage king, Árpád Salamon, and Werner has two children, Otto and Ida, with which to forge the alliances necessary to take Salamon’s throne for a more worthy candidate.

Hungary has a virtual buffet of attractive, young, and hopefully fertile princesses. There’s only one hiccup in Werner’s plan: he’s already married to a lowborn woman named Reginlind, and even if the Pope cared about a backwater count in Switzerland, Reginlind has given no cause for His Holiness to grant Werner a divorce.

However, the one benefit of marrying a commoner is that no one cares about her life, so Werner hardens his heart and orders Reginlind imprisoned and then hanged, her neck breaking to match her heart. To ease his troubled mind, Werner begins a pilgrimage to Rome. Scholars would wonder for years why Werner didn’t spare Reginlind and order her to join a convent once she was at his mercy in the dungeons, and their colleagues would point to Werner’s low learning skill and to a particularly incompetent advisor who went straight to the prisoner screen instead of the targeted decisions menu.

Returned from Rome with what Reginlind would almost certainly consider an ironic newfound appreciation for charity, Werner begins planning his second marriage. His new bride is the 17-year-old Princess Árpád Mária, a woman with a head for sums and money, although her self-restraint meant she sometimes passed the most lucrative opportunities.

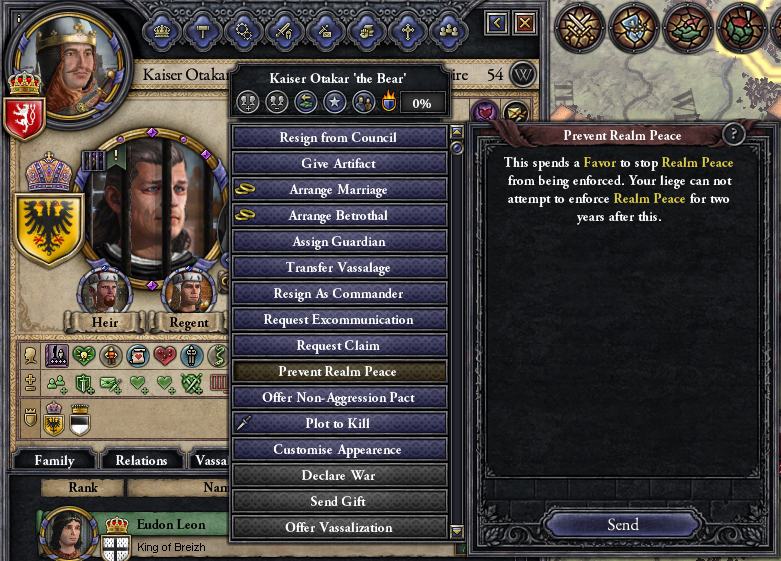

While on pilgrimage, Werner had written back to his regent, Bishop Simon of St-Ursanne, to arrange the betrothals for his children. Ida’s hand was promised to Prince Bretislav Premyslid of Bohemia, eldest son of Duke Vladislav. With this pact Werner gained the backing of the second-largest military force in the empire: 3,400 levy troops and counting. However the Bohemians would be a belated reinforcement should an enemy attack close to home, so Otto, the heir, was matched with Gisele d’Ivrea, third daughter and sixth child in total of Duke Guillaume of the neighboring realm of Franche-Comté. For extra insurance Werner got a written agreement of mutual defense signed by his brother-in-law in Bern.

|

|

With these three pacts, Werner now has access to an army six times that which he could have raised on his own. And none too soon, for King Árpád Salamon is drawing near the age of majority and his coronation within the next two years. After that day, his reign will be too legitimate in the eyes of Werner’s new allies, and he will not be able to call them to depose Salamon in favor of his cousin, the new Baroness of Habsburg.

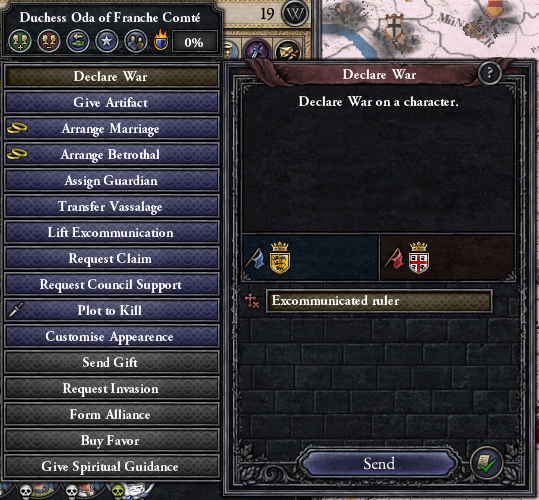

And so, on 21 February, 1067, the fourteen-year-old King of Hungary receives a sealed scroll of cheap parchment informing him that a minor Swiss count is declaring war to press his cousin Mária’s claim to his throne. Salamon promptly snorts with laughter and asks his regent, the Queen Mother Anastasia of Rus, if she was trying to audition for the title of court jester. His mother replies sternly that this is a legitimate diplomatic missive and reads a second letter from the Duke of Bohemia. Salamon’s laughter cuts off abruptly, and within the hour messengers are on their way to every corner of the Carpathian Basin, calling all loyal sons of Hungary to war.

Salamon’s forces manage to win an early victory at Esztergom against Count Werner himself in 1068, but the Lord of Basel regroups his coalition’s forces and leads them to a victorious rematch at the Second Battle of Esztergom in January of the next year.

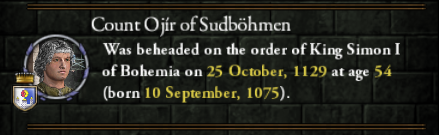

In February of 1069, while the Habsburg forces are in the process of laying siege to the Hungarian capital of Esztergom, Werner realizes one ally hasn’t yet appeared: the Duke of Franche-Comté. Werner soon discovers why: the treaty of alliance he had meant to send for the Duke’s signature had been left on his desk at Habsburg Castle! One swift horse and one beheaded advisor later (rumored to be the same dullard who had “conveniently” forgotten about the existence of nunneries during the Reginlind debacle) and Duke Guillaume’s banners are crossing the Danube to aid in the capture of King Salamon’s personal holdings.

A third and final battle of Esztergom takes place when the coalition arrives to break a siege against their garrison by King Salamon’s main army, desperate to reclaim the capital. Werner distinguishes himself as a specialist in the skilled deployment of heavily-armored infantrymen, while the king distinguishes himself by losing his right eye in a battlefield duel. Unfortunately for posterity, so many of the allied commanders claimed to be the man who took the king’s eye (some even brandishing macabre trophies ostensibly from the royal head) that the true identity of Salamon’s opponent that day has been lost to history. Salamon himself, rather than offer up any useful information, would instead offer up a jest when asked if he had any idea: “How should I know? He came at me from the right!”

By May of 1070, even the now half-blind Salamon can see the writing on the wall. On the morning of the 15th, he walks into the throne room of Komárom Castle in Esztergom, dressed in full regal attire. He sits on the throne as a board is laid on his lap, a roll of parchment rolled out on it, and a quill placed in his hand. The young king reads the proclamation in Magyar, his voice stirring the audience with its combination of honesty and righteous indignation towards his enemies. Then he signs his name, presses his royal seal in wax next to it, and hands the parchment to the court chamberlain. The board is taken away, Salamon rises, and his court kneels before him one final time as he turns and lays his scepter, his robe, and finally his crown on the throne. Retaking the parchment from his chamberlain, he walks silently to the front steps of the palace, where Mária and her shabbily-dressed husband are waiting. The normally talkative Salamon says not a single word to his cousin, any remaining familial love for Mária buried deep behind an icy stare, as he hands her the official notice of his abdication. He passes by Werner on his right, so as to avoid even the pretense of a glance to acknowledge the count's existence, and begins the journey to his new seat in Sopron, trying not to hear the crowd behind him chanting, “Long live Queen Mária!”

|

|

Edited on 2020.5.21 to correct Bohemian troop counts, which I had somehow doubled in my head.

Next Time...

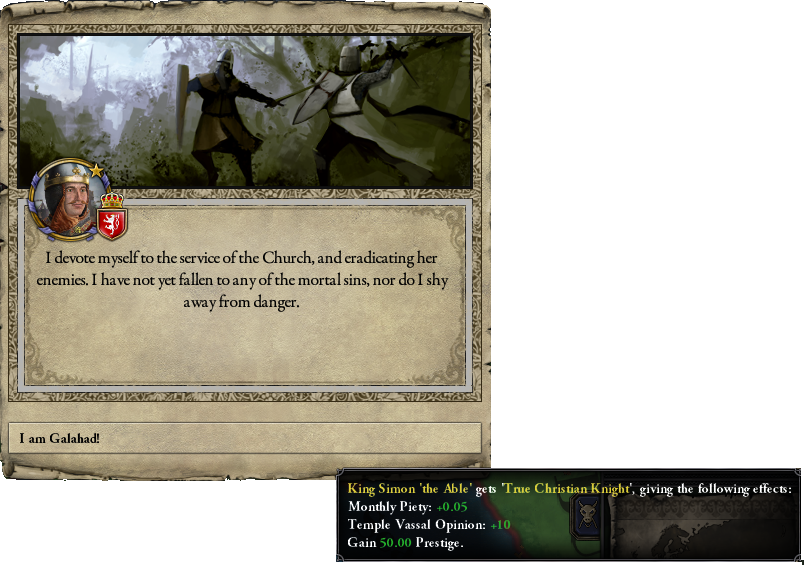

Count Werner receives tidings both good and ill, and young Otto begins to walk a path of darkness...

Last edited:

- 2

- 1

.png)

.png)