Prologue: the rise of the House Roderlo

The exact origin of the Roderlo’s isn’t known. The first mention of their ancestral castle comes from 1320, only 16 years before they would come to possess the Duchy of Gelre. At the time, the father of Johannes “IJzervreter”, Hendrik, was the lord of Castle Roderlo/Reurlo (both names are correct). It was not a very impressive castle, to this day it remains very small, just like the city of Reurlo that came into existence nearby, something strange for what can be considered one of the great dynasties of Europe.

Castle Roderlo/Reurlo, to this very day it houses members of the House Roderlo

The first mention of the castle immediately begins the rise to power of the Roderlo’s. In 1320, Hendrik married the eldest daughter of count Reinoud II. At the time, Reinoud was a young man, in his late twenties, and married to Elanor of England, eldest daughter of Edward III, King of England. An interesting fact is that his mother was Margareta of Dampierre, daughter of the famous count Gwijde of Dampierre of Flanders, the man who would lead Flanders in revolt against the Kings of France, and to this day a regional hero. (Through this relationship the Roderlo’s would later base their claim on the County of Flanders after the Dampierre’s lost the county.) The marriage of his eldest daughter to a local noble was mainly to encourage better relations with the nobles of the County of Zutphen. At the time, the county was in a strong personal union with Gelre, but it remained the most uncontrolled part of his realm. It was the Lordship of Borculo that oftentimes defied the wishes of the counts. At the time of his marriage, he did not have a male heir, his younger brother had passed away in 1315 for reasons unknown. But, as he was young, it was assumed that he would eventually have a male heir. And he did, in 1333, his son Reinoud was born.

Reinoud II, the last count of the House of Gelre

For the moment we will look at Hendrik and his wife Margareta. It seemed that she liked to be away from the “hectic” court in Nijmegen. She enjoyed walking through the forests with Hendrik. And with there not being many obligations for Hendrik, he actually took a liking to his wife. For the birth of their first child, which was within a year of their marriage, they had a priest come over from the Bishopric of Utrecht, and from the texts he wrote whilst in Reurlo, it seems that Hendrik and Margareta had actually fallen in love, a rarity in a world where noble marriages just existed as political tools to make alliances and expand one’s domain. It sadly, wasn’t long to last. 3 years later, when giving birth to their second child, a girl, both Margareta and the girl passed away. Hendrik, out of faithfulness to his wife, decided not to marry again.

Back in Nijmegen, over the years, Reinoud and his wife got more children. But it took until their 5th child that a male heir was born, also named Reinoud, named after his father, just like his father was. 2 years later, in 1330, a second son was born, named Eduard, after his grandfather. And this is the situation that remained for 7 years. Reinoud was father of 6 children.

1336 would be a faithful year for Reinoud. In May, he announced a hunt for all the nobles of his realm in the forests of the Veluwe. We know for certain Hendrik attended this hunt. We don’t know if the young Johannes attended this hunt. But what we do know is that both of Reinoud’s sons attended the hunt, probably because of a lot of begging on the part of the eldest. And whilst we do not know what exactly happened, sources state a differing reasons, what we do know is that both of Reinouds sons died during the hunt. Reinoud, devastated by this loss, and feeling guilty because he permitted them to join him on the hunt, retreated to his chambers. When days later an aide built up the courage to enter his chamber, he found him dead, having committed suicide.

What began was a scramble by multiple nobles to claim the vacant throne of Gelre and Zutphen. Internally, the powerfull Bronckhorst and Heeckeren families put forward their candidates, both with connections to the old Gelre dynasty. From across the border, the Dukes of Cleves put forward a claim on Gelre and Zutphen. It had been the strategic goal of the Counts of Gelre to control the traderoutes from Antwerp to the east. Had Cleves joined into a union with Gelre, this long-term goal would have been completed, and it wasn’t something opposed to the goals of the local nobility. In the east, the Lord of Borculo showed some interest in the Gelrian throne, receiving some support from the Bishop of Munster. Lastly, there was the legitimate pretender of the Gelrian throne, son of the eldest daughter of Reinoud, Johannes Roderlo.

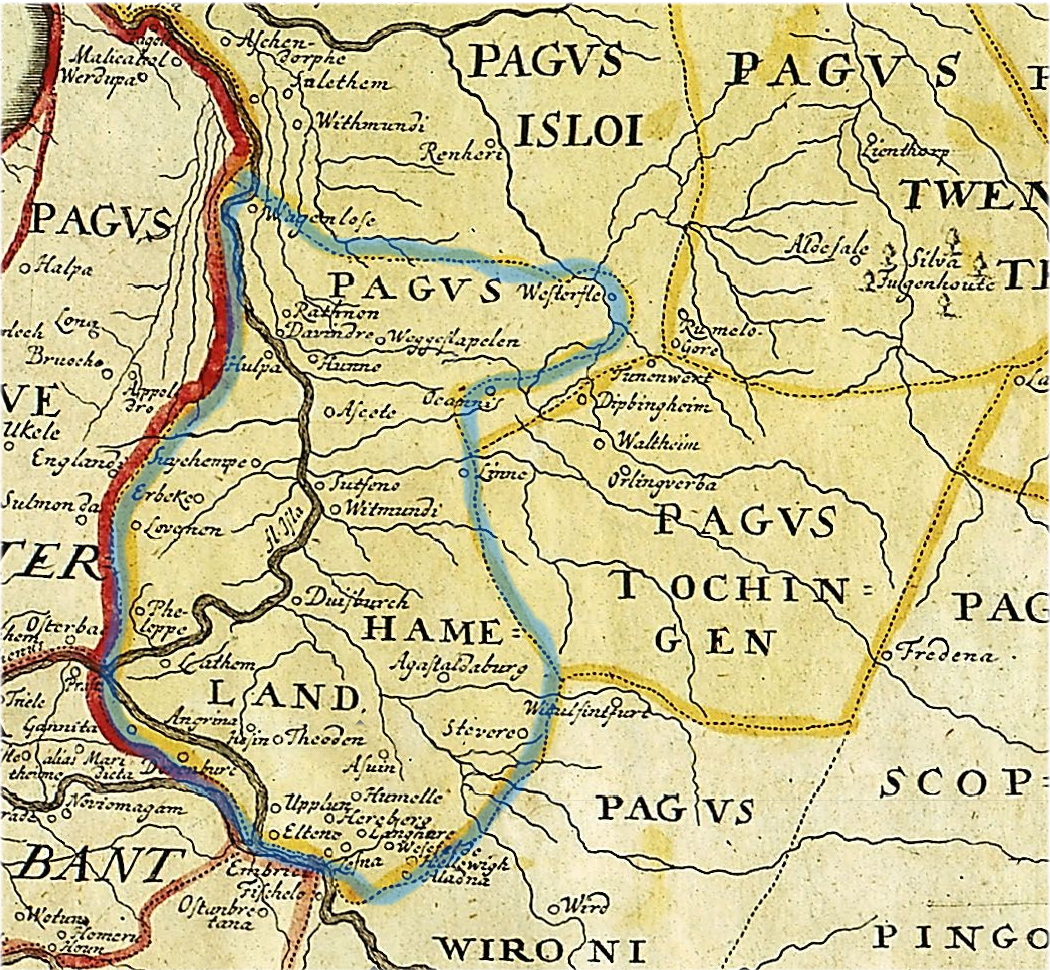

The Lordship of Borculo, for a long time independent from Zutphen, but under heavy influence from the west. The city of Grolle in her centre was under the rule of the counts.

Whilst The Bronckhorsts and Heeckerens fought head to head over influence within Arnhem, Nijmegen and Gelre, to the east, Johannes was making smarter moves. The first one to drop out of the race was the Lord of Borculo. Even if the Bishop of Munster had fully committed to his cause, it would have been unlikely that he would have gained the counties. But this didn’t mean that he was powerless. If he couldn’t gain it himself, he could help a friend. Relations between the Lords of Borculo and the lords of Castle Roderlo had always been friendly. So, the Lord of Borculo threw his lot in with Johannes, and with him came the blessing of the Bishop of Munster. Also, a deal was signed which would, in the case that Johannes gained the titles, that Borculo would officially recognize the authority of the counts, but it would retain a large number of special privileges.

Ironically enough, after securing support from the church, Johannes travelled to the court of Emperor Ludwig IV of the Wittelsbach dynasty. This was at the height of the Investiture Controversy. The Hohenstaufen dynasty had battled a long time in Italy with the Papacy, and at this point in history the Papacy was actually located in Avignon. Ludwig was interested in allies who could help combat the power of the church, even if it meant the increase of the power of the nobility, because “at least I (Ludwig) stand above a noble, only God stands above a Bishop”.

In the Lowlands at the time, there were two powerful bishops. The Bishop of Luik, an office which controlled lands stretching from France to the Rhine, but more importantly, the Bishop of Utrecht, which controlled Utrecht and the surrounding lands (Nedersticht) and the lands between Gelre and Zutphen in the south and the Frisian freedom in the north (Oversticht). It is also the Frisian freedom which is interesting. It is best characterized as a series of farmer republics (Bauerrepubliken/Boerenrepublieken), a collection of small communities ran by farmers, peasants, lower nobility and city-dwellers (in what manner cities existed in Frisia). Generally, the lands north of Gelre and Zutphen were far away from the influence of whatever emperor ruled at the time. It was in this situation that Johannes came with an offer.

Johannes was an ambitious man, and the ambition that showed later in his life is already quite obvious. His offer was simple. Recognize his claim to the counties of Gelre and Zutphen, elevate Gelre and unify the titles (it would become the Duchy of Gelre and County of Zutphen, one title), and grant him overlordship over Oversticht and the Frisian lands. In exchange, he would make himself a loyal subject of the Emperor, supporting his preferred candidate for the Emperorship (the system of Electors was yet to be codified) and sending money and men to the Emperor when he needed it. The elevation to a Duchy was something that was already planned for a longer time, Gelre was quite a power to be reckoned with in the Lowlands, and it would provide a counterbalance to the powerful Dukes of Brabant, who were the heirs of the Duchy of (Lower) Lorraine. It is often said that Johannes’ proposal was too one-sided. After all, the word of a vasal was often worth nothing if breaking it meant that he would gain something. But Johannes was a capable diplomat, and after some discussion about minor details, Ludwig accepted his proposal. Johannes, if he gained the throne, would be elevated to a duke and receive carte blanche to tackle the power of the church and the farmer republics in the Lowlands.

With this, he returned home. And whilst he was gone, the situation in Gelre had deteriorated. The Bronckhorst and Heeckerens had been preparing for war, and it was obvious that if both weren’t stopped, a civil war would break out in the duchy. In this climate, Johannes stepped forward to press his claim. By all intents and purposes, he was the rightful count, and was supported by the Bishop of Munster and the Emperor himself. And the obvious alternative was a civil war between the Bronckhorst and Heeckerens. Those families saw their support melting away in the face of that threat. And thus, Johannes became Johannes I Roderlo, count of Gelre and Zutphen in late November 1336. On Christmas Day, he would be, with blessing of the emperor, be crowned duke by the Bishop of Munster.

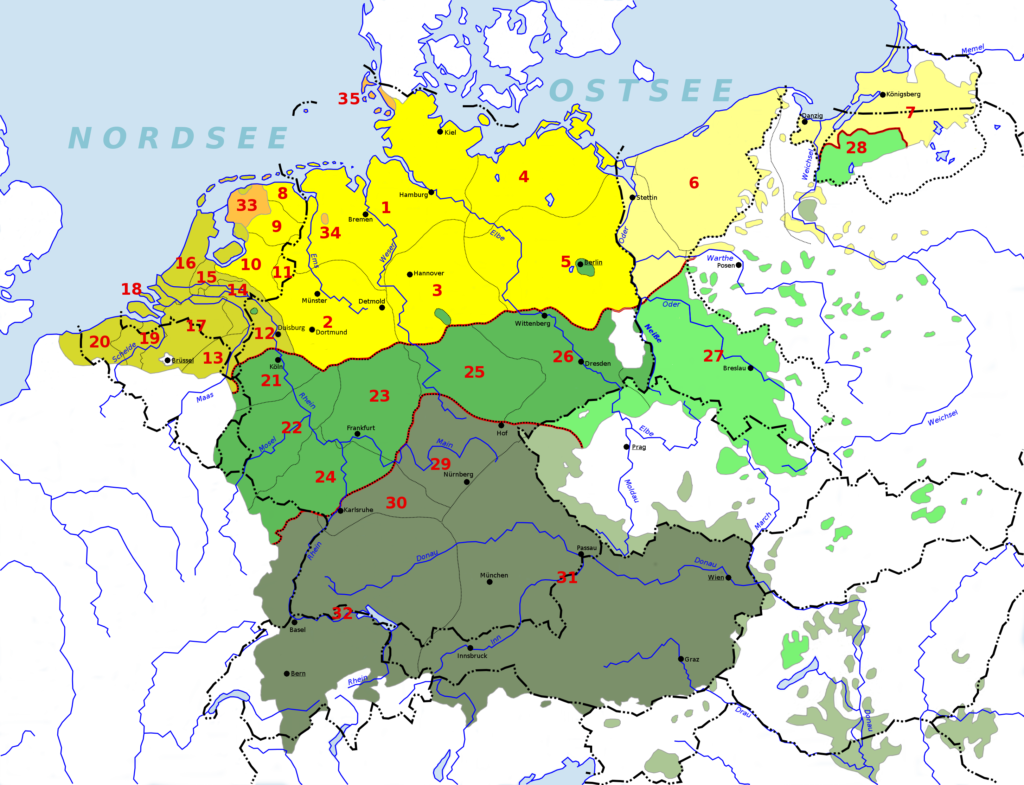

Johannes was an ambitious man, those who know the history of the Roderlo’s and of Saxony are well familiar with that. Thus, to consider the position he found himself in on the first day of the ducal throne, we must look to the west and to the northern parts of the HRE. The old Stemduchy of Saxony was long gone. In the east, near the Elbe, laid the last remnants of this Duchy, divided in the late 13th century.

There was a much more powerful family in the northern HRE besides the Ascania’s who held a successor state to the old Stemduchy. This was the Welfs who held the Duchy of Brunswick. The Welf dynasty had actually held the ducal title for a while. It were the Welfs who had oversawn the end of the duchy. In the late 12th century, they refused to support Emperor Barbarossa’s campaigns in Italy, which eventually lead to a revolt against the Emperor and the other nobles of the realm. There had been some success, but in the end, the Welfs lost. The Duchy of Saxony seized to exist. The Welfs did retain their other personal possessions in the now defunct duchy. These would, in 1235, be elevated to a duchy themselves, the Duchy of Brunswick.

The lands of the Duchy of Brunswick, covering most of the old Stemduchy

To the east of Brunswick laid what was, at least in name, the nominal successor to the Stemduchy. The title of “Duke of Saxony” had been granted to the Ascania family after the dissolvement of the duchy. The Ascania’s were in some ways the rivals of the Welfs. Before Henry III would oversee the dissolvement of the duchy, Albert “the Bear” of the Ascania’s ruled the duchy, although this was a disputed status. The ducal title had been rescinded from the Welfs and granted to Albert, but only if he could take control of it, which he obviously couldn’t.

It must also be mentioned that from 1180 onwards we don’t speak of the Ascanian Duchy of Saxony as Saxony anymore. Some historians prefer to name these the Elder and Younger duchy’s. But, with the Roderlo’s later restoring the Duchy propper, this naming is considered confusing. So from 1180 we consider the old stemduchy gone, with the Ascania’s holding the Duchy of Wittemberg, which is the successor to the old stemduchy.

The lands of the Ascania’s, not worthy of the title “Duchy of Saxony”, with half of it outside of the Stemduchy

From the realm of the Ascania’s we travel further east, to a holding of the Wittelsbachs, the Margriavate of Branderburg. Brandenburg was a recent acquisition, only coming into their hands in 1323. But, Wittelsbach rule of Brandenburg was not completely stable. Since the Wittelsbachs were a dynasty based mainly from Bavaria, they were seen as foreigners by the local nobility. It didn’t help that they often cared more about other possessions throughout the Empire. And at the time, the Wittelsbachs held the Imperial title, so a far away, underdeveloped corner of the empire wasn’t of the highest priority. In some ways, the margraviate stood separate from the politics west of the river Elbe, but a few parts of her domain were on the other side of the river.

The Margraviate of Brandenburg, not a power “native” to the old duchy but certainly a player within her old lands

Heading to the north, we reach the city of Lubeck, the city that was to become the centre of the Hanseatic League. In 1337, the League had not officially been founded but merchants from the north of the HRE had already become a major force in the Baltic trade, having long ago overcome their rivals from Visby. We can also trace the rise of this merchant power back the Duchy of Saxony. Henry III, the last duke, had conquered the area and rebuilt the town in 1159. Lubeck’s location made it an ideal spot as an international, or at the least in the Baltic and northern HRE, hub for trade. In 1337, her influence spread from Novgorod in the east to as far as Kales and London in the west.

Extend of the Hanseatic trading network throughout the Baltic and North Sea

It is ,of course, also impossible to talk about the history of the Roderlo’s, and especially impossible to talk about Johannes, without mentioning the claim he made and later pressed.

According to the documents written down at the time, Johannes claimed that Wigbert, Widukind’s son, had two daughters, Wulfhilde and Mathilde. So, upon his death in 827 , the County of Hamaland and Duchy of Saxony reverted back to the Emperor, who at the time was Louis the Pious, son of Charlemagne. From 827 to 850, the Duke of Saxony is unknow, with the Frankish noble Liodulf being appointed duke in that year. He is the founding father of the Ottonian Dynasty, the Dukes of Saxony who would eventually become King of Germany and unite the Kingdom of Germany, Kingdom of Lotharingia, Kingdom of Arles and Kingdom of Italy into the Holy Roman Empire.

After the death of Wigbert, we do know that the Saxon noble Wichmann Billung was made the count of Hamaland. A daughter of his married Duke Liodulf. And a younger son (we do not know, but he had at least 4 sons) married Wulfhilde. From there on, we have some on and off documentation about their descendants. They generally stuck around the Lowlands and Saxony areas. Some joined both the 2nd and Baltic Crusades, but they either died or didn’t have any known descendants.

Through a male line we can trace the blood of Widukind all the way to the late 13th and early 14th centuries. By this time, the name Billung had long fallen out of use, everybody just being referred to as “Of [first name of the father]”. We know that a man named Hendrik sent to the border of the County of Zutphen with the Lordship of Borculo, where he was to construct a castle. And this is of course the father of Johannes.

Now it comes to the validity of this claim. Today, it is widely accepted that the Roderlo’s are indeed descendant from Widukind. But, we must also consider that every noble on the continent can in one way or the other claim to be a descendant of Charlemagne, not to forget that history is written by the victors, and that this might influence the way that certain gaps in the lineage have been judged.

But, even considering this factor, the small gaps in the documentation considered, we can conclude with reasonable certainty that the Roderlo’s are indeed the Heirs of Widukind.