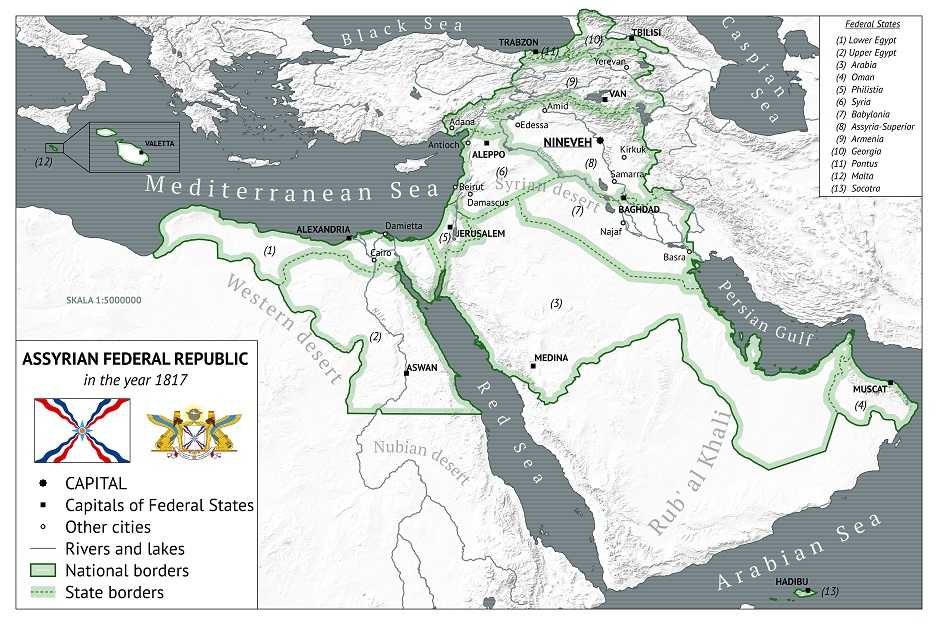

The Federal Republic of Assyria in 1817

The Federal Republic of Assyria was a land defined by natural geography: three great rivers - the Euphrates, Tigris and Nile, a barrier of mountains in the Tauros, Armenian Highlands, Caucuses and Zagros across its northern and eastern frontiers, the great expanses of deserts in the south and the maritime arteries of the Red Sea, Persian Gulf and Mediterranean that connected it to the outside world.

As the cradle of world civilisation and home to many of the most important religious sites in the world, it also bore the heavy weight of thousands of years of history. Its peoples were dizzying in their religious and ethnic diversity. No single ethnic group made up more than a quarter of the population, with Arabs, Copts and Assyrians all constituting around a fifth of the total and Armenians only a little less with a dozen further ethnic groups constituting the remainder of the population. While the Republic was overwhelmingly Christian at 87%, it was divided between dozens of Churches and denominations including Nestorians, four further Syriac Churches, Catholics, Oriental Orthodox, two separate Greek Churches and even Protestantism. Meanwhile, a tenth of the population were Muslims while the country was also home to one of the strongest Jewish communities in the world.

While the nature of this tapestry had been known for centuries, it was not until the first Assyrian census in 1817 that it was fully and accurately quantified for the first time.

With a total population of 15,388,166, the Middle East no longer had the demographic weight globally that it had once had. Indeed, the population of Assyria had begun to stagnate in the seventeenth century and even declined in the eighteenth while much of the world saw growth, and with the advent of the industrial revolution Europe was in the early stages of a demographic explosion.

States of Assyria

1. Lower Egypt

Majority Ethnicity: Copts

Majority Religion: Catholicism

Other Ethnicities: Latins, Blacks, Assyrians, Jews, Misri Arabs

Other Religions: Protestantism, Old Coptic, Nestorianism, Judaism

2. Upper Egypt

Majority Ethnicity: Misri Arabs

Majority Religion: Sunni Islam

Other Ethnicities: Copts, Blacks, Sudanese

Other Religions: Catholicism

3. Arabia

Majority Ethnicity: Bedouin Arabs

Majority Religion: Sunni Islam

Other Ethnicities: Blacks, Persians, Assyrians

Other Religions: Shia Islam, Nestorianism

4. Oman

Majority Ethnicity: Omani Arabs

Majority Religion: Sunni Islam

Other Ethnicities: Blacks, Persians

5. Philistia

Majority Ethnicity: Mashriqi Arabs

Majority Religion: Catholicism

Other Ethnicities: Latins, Cumans, Assyrians, Bedouin Arabs, Jews, Armenians

Other Religions: Nestorianism, Protestantism, Judaism, Shia Islam, Sunni Islam, Oriental Orthodoxy, Sassinitism

6. Syria

Majority Ethnicity: Mashriqi Arabs

Plurality Religion: Paulician Orthodoxy

Other Ethnicities: Assyrians, Armenians, Greeks, Jews, Blacks, Latins

Other Religions: Old Orthodoxy, Nestorianism, Messalianism, Maronite, Sassinitism, Druze, Judaism, Oriental Orthodoxy, Catholicism, New Nestorianism, Shia Islam, Protestantism

7. Babylonia

Majority Ethnicity: Mashriqi Arabs

Majority Religion: Nestorianism

Other Ethnicities: Assyrians, Blacks, Kurds, Mandaeans, Jews, Persians, Armenians

Other Religions: Zikri Islam, Shia Islam, Sassinitism, Mandaeism, Judaism

8. Assyria-Superior

Majority Ethnicity: Assyrian

Majority Religion: Nestorianism

Other Ethnicities: Armenians, Kurds, Cumans, Mashriqi Arabs, Jews

Other Religions: sassinitism, Oriental Orthodoxy, Catholicism, Judaism, New Nestorianism

9. Armenia

Majority Ethnicity: Armenian

Plurality Religion: Oriental Orthodoxy

Other Ethnicities: Assyrians, Greeks

Other Religions: Old Orthodoxy, Nestorian, Paulician Orthodox, Sassinitism, New Nestorian

10. Georgia

Majority Ethnicity: Georgian

Majority Religion: Old Orthodoxy

Other Ethnicities: Armenian

Other Religions: Oriental Orthodoxy, Paulician Orthodoxy

11. Pontus

Majority Ethnicity: Cuman

Majority Religion: Catholicism

Other Ethnicities: Greeks, Armenians

Other Religions: Paulician Orthodoxy, Old Orthodoxy

12. Malta

Majority Ethnicity: Maltese

Majority Religion: Catholicism

13. Socotra

Majority Ethnicity: Socotran

Majority Religion: Nestorianism

Other Ethnicities: Blacks

Religion in Assyria

Orange - Nestorian

Yellow - Catholic

Red - Old Orthodoc

Dark Red - Paulician

Turqoise - Oriental Orthodox

Purple - Messalian

Brown - Maronite

Green - Sunni

Dark Green - Shia

Light Green - Zikri

Teal - Druze

| Denomination | % | Number |

Syriac | Nestorian | 29.1 | 4,480,542 |

| Sassinite | 3.4 | 523,198 |

| New Nestorian | 1.8 | 275,401 |

| Messalian | 1.7 | 263,138 |

| Maronite | 0.8 | 120,102 |

Catholic | Catholic | 25 | 3,840,301 |

Greek-Rite | Old Orthodox | 7.8 | 1,202,211 |

| Paulician | 4.1 | 635,531 |

Other Christian | Oriental Orthodox | 7.6 | 1,168,076 |

| Protestant | 5.4 | 832,781 |

Muslim | Sunni | 7.6 | 1,164,884 |

| Shi’ite | 1.9 | 296,992 |

| Zikri | 1.2 | 175,425 |

Other | Jewish | 2.1 | 322,770 |

| Druze | 0.3 | 52,115 |

| Mandaean | 0.2 | 34,699 |

| | | |

| Total | | 15,388,166 |

Syriac Christianity 36.8% (5,662,381)

Far more than the ethnic Assyrians themselves, the followers of Syriac Christianity – denominations that used Syriac in their liturgies and for the most part drawn from a shared Nestorian tradition, were the core of the Assyrian Republic. Syriac Christianity was by no means a unified communion. Despite connections of history and to an extent theology, its component Churches were all strictly separate and often mutually hostile to one another. This was especially the case for the most recent splinters from the Church of the East – the Sassinites and New Nestorians. Nonetheless, they inhabited a distinctive shared cultural world in which Mesopotamia, Beth Nahrain, the Syriac language and Assyrian nationhood were central.

Nestorianism 29.1% (4,480,582)

The Church of the East was formed in the fifth century as a national Church of the Sasanian Persian Empire. From its early days it came under the influence of the disciples of Nestorius, who had been expelled from the Roman Church, and eventually adopted much of his theology. The important of these distinctive Nestorian ideas regarded the nature of Christ – Nestorians believing that He possessed to distinct and separate natures within a single – and the role of Mary, whose significance was downgraded by Nestorians who rejected her label as the God-bearer.

For centuries the Church flourished. It became the majority faith in its Mesopotamian heartland, and attracted communities across Asia – including through the rest of Iran, along the Silk Road in Central Asia and even far away China and, famously, among the Malabar Christians of southern India. However, the rise of Islam in the seventh century began a period of decline. Although the Church enjoyed greater toleration than it had under Zoroastrian Persian rule, it saw its heartland ripped from it as Mesopotamia underwent a gradual process of Islamisation and Arabisation, with the Nestorian Christians gradually dwindling into a small minority.

In the power vacuum brought about by the collapse of Seljuk power west of the Zagros in the early twelfth century, everything changed after a small-time Christian tribal leader named Ta'mhas Qatwa captured the city of Samarra and within a single generation carved out the Kingdom of Assyria. As Ta'mhas invited the Nestorian Patriarch to move from Baghdad to take up residence in the Assyrian capital of Nineveh, the Church of the East became an established Church of state for the first time in its history. Through the next several centuries of the Medieval era under the Qatwa it enjoyed continuous growth, becoming the main religion of Mesopotamia once more and gained worshippers across the Middle East. Influenced by the Latin Crusaders of Palestine and Egypt, the Church even developed a Crusading tradition of its own – with the thirteenth century seeing the First Malabar Crusade sent to liberate the St Thomas Christians of southern India from Hindu rule, creating a Christian Raj that would last for nearly a century and inspire two further Crusades in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

After its High Medieval rise, the Nestorian Church endured a more difficult period from the fifteenth century. The century began with the short-lived conversion of King Sabrisho to Zikri Islam and shortly thereafter the extinction of the sacred Qatwa bloodline of Saint Ta'mhas. The Qatwa's were succeeded by a foreign monarch, the Armenian Aboulgharib. While the new King converted to Nestorianism, his ecumenical policies – allowing from toleration of other Christian sects and the dispersion of political power to different Churches across the constituent Kingdoms of Assyria – robbed the Church of the East from the high status it held during the Middle Ages, a place it would never fully regain even as its influence spread throughout the Indian Ocean through the Assyrian colonial empire.

The attempt of Queen Gergana, the second of two Egyptian Catholic monarchs, to bring the Church of the East into the Roman fold and impose Chalcedonian theological doctrines was the spark for the Marian Revolution as Nestorian mobs sparked an uprising against the Egyptians and led to the formation of the Federal Kingdom. Nestorian popular power would rear its head again in the 1580s, to spare Assyria from annihilation at the hands of the Byzantines and begin a period of absolutist rule in the seventeenth century during which the Church's influence rose once more, even as it was challenged by the emerging Sassinite movement. However, following the death of Yeshua II there was a move against the Church once more as his successors in the House Laboue-Amarah proved tantalised by secular modernity at the expense of religious tradition. This would lead to the intertwining of the Church with reactionary conservatism for the next century - the Nestorian clergy being central to the First Lebarian Revolt and the White Army of the Revolutionary Civil War.

The Revolution would lead to one of the most painful moments in the Church's recent history with the Schism of 1744. With the Patriarch leaving Nineveh and aligning himself openly with the counter-revolutionary cause, liberal clerics in the capital gathered to depose him and elect a replacement at ease with the Revolution. This division endured long after the flames of civil war had gone out, with the Republican Church controlling much of the infrastructure of the Nestorian Church, while the exiled conservative Patriarchate retained the loyalty of the majority of the Syriac flocks' souls. This divide was eventually healed in 1792 after the Vizier Chozai Petuel invited the exiled Patriarch to return to Assyria and pressurised the Republican Church into unification. This resulted in the restoration of the Church of the East under a single leadership, carrying the overwhelming majority of the faithful.

In 1817, the Church of the East was the largest religious current within the Federal Republic, narrowing outweighing Catholicism. The majority faith in Mesopotamia – with four fifths of Babylonia and somewhat more of Assyria-Superior being followers of the faith. It was also the majority religion among the Bedouin tribes of the Persian Gulf, on the east bank of the Jordan River in Philistia and in eastern Syria. Meanwhile, there were Nestorian minorities scattered across every corner of the Republic, from modestly sized minorities in the large cities of Lower Egypt to significant concentrations in Armenia, southern and western Syria and around Jerusalem and the west bank of Jordan. Its numbers extended far beyond its ethnic Assyrian core, which formed barely half of its total population, to the West Kurds of Assyrian-Superior, Armenians both within and outwith their home state, Arab speakers in Babylonia, the Levant and Gulf, and even many of the Blacks who professed the religion of their masters.

Sassinitism 3.4% (523,198)

The Sassinite faith originated in the idiosyncratic teachings of the Syrian preacher Avira Sassine in the late seventeenth century. Raised in the Church of the East but heavily influences be Messalian doctrines, Sassine's religion was infamous for two aspects – its unusual practices and radical philosophies. These practices focussed on putting the physical body through extremes of both hardships through long fasts and self-flagellations and sensation in orgiastic rituals. Meanwhile, it held up a core egalitarian philosophy that all men were equal, seeing slavery in particular as the greatest of all evils. Sassine spent much of his life preaching among the enslaved Blacks, attracting a large following among them. While Sassinites, denounced as illegitimate heretics by the Nestorian Church faced persecution in the late seventeenth century, their fortunes turned in the new century. In this period their adherents would form the first Abolitionist societies – one of the building blocks of the future Ishtarian political movement and, allegedly, gained the ear of Emperor Niv IV himself for a time – contributing to the outbreak of the First Lebarian War in 1728. During the Revolution, many Sassinites played prominent roles at the forefront of Liberal radicalism – one of their own, Nuri Ardalan serving as Vizier during the Revolutionary Terror. After the triumph of Malik Abaya, Sassinites would play an outsized role in keeping the flame of Ishtarianism and Abolitionism alive through its longest and hardest years.

The Sassinite Church, far more decentralised than the other Christian denominations in Assyria and lacking in a single leadership figure, had variations in its exact practices from place to place. It hard particular strength among the Blacks, in particular the slaves of Babylonia – among whom Sassine himself had preached – and the ghettoised free Blacks of Syria and Assyria-Superior. Away from these concentrations, the faith held sway many communities across the Levant, Mesopotamia and Armenia – with its greatest strength in the cities and among the middling classes. Even at the dawn of the nineteenth century, Sassinites were despised not only by Nestorians but many other denominations as heretics, sinners and alleged supporters of miscegenation, sex between the races.

New Nestorianism 1.8% (275,401)

The newest, or according to its adherents one of the oldest, religious denominations in Assyria was the 'New Nestorians'. This was a Church formed by those who rejected the reunification of the Church of the East under conservative Patriarchal leadership in 1793. Rejecting the ecclesiastical council that had facilitated this, they claimed the status as the true, legal and spiritual continuation of the Church of the East. However, given their marginal size relative to the much larger reunified Church, outside of their own circles they were described as the New Church of the East of New Nestorians. Unlike the sassinites, the New Nestorians had few substantive theological differences. Their disputes with the mainline Church were administrative and political. They saw the suspension of the normal practice of electing a new Patriarch in 1792 and the assumption of a cleric from outwith the official Church to the Patriarchal seat as fundamentally illegitimate. Equally, its clergy and parishioners held to generally liberal and republican beliefs – seeing religion as a personal matter with no place in influencing the state or secular world, a feared a resumption of conservative Nestorianism would lead to a corrupting mingling of the spiritual and secular. Geographically, the New Nestorian schismatics drew only a handful of Episcopal Sees with them in their split – concentrated solely in the core Republican territories of Syria, Assyria-Superior and Armenia.

Messalianism 1.7% (263,138)

The Messalians had one of the most incredible histories of any community in Assyria. They traced their origins to the second half of the thirteenth century, as the Kingdom of Assyria recovered from the ravages of the Black Plague large sections of the peasantry became attracted to groups of lay preachers known as the Messalians who preached egalitarian ideas against the wealth and corruption of the Church and the landed and commercial elite. Above all the blamed the Jews, identified closely with commerce and corruption, as the source of the people's woes and demanded that they be cast from the land. After the Patriarch and Church hierarchy denounced anti-Semitism, the Messalians took matters into their own hands – stoking pogroms and rebellions. Under the leadership of the preacher Yeshua Dinkha they stormed Nineveh in 1279 and gruesomely executed King Moqli by crowning him with a burning iron crown, leaving them in control of the heart of the Assyrian state and sending the realm into an anarchic civil war. After a decade of fighting King Niv the Hammer reconquered the capital, crucified Dinkha and crushed the Messalians through brutal persecution. The sect only survived after a few believers were able to escape across the Syrian Desert – eventually settling around Damascus.

This was far from the end for the Messalians. Over the next decades the community formalised their religion around a structured Messalian Church and a powerful Bishop, who ruled as their secular and spiritual master. The Church grew rapidly in its new home – become the largest religion in southern Syria east of Mount Lebanon. At the end of the fourteenth century they intruded on Assyrian history in spectacular fashion for a second time. Rising in rebellion while the Assyrian state sparred with the Timurids in the east, the Messalians captured King Eliya in battle and had him blinded. While they were eventually put down once again, and their dreams of independence permanently ended, there was no second effort to destroy the community once and for all and in the centuries ahead it would only further ingrain itself in southern Syria. There, they developed an unusual society that was far more egalitarian than anywhere else in Assyria, with few great landowners or wealthy merchants.

As modernity approach, Messalian ideas would be particularly influential in the development of radical ideas – influencing both the Sassinite faith and its Abolitionist sentiments and Liberal Ishtarianism, in particular its most radical elements that stressed material equality. Indeed, the Messalian political leader Ephrem Karim served as Vizier between 1742 and his death in 1744 and took the Revolution towards one of its most radical phases. Like the Sassinites, the Messalian community remained a core component of the Ishtarian electoral coalition even as Liberalism endured a steep decline during the post-revolutionary years.

Geographically, the Messalians were tightly grouped in their home territory in and around Damascus and the hills and valleys to its west. Although originating among the Assyrian peasantry of Assyria-Superior, the Messalians were Arab-speaking by the nineteenth century, although the Messalian Church used Syriac as its liturgical language and knowledge of Syriac was common. While they dominated the countryside around it, Damascus itself was more diverse, with Messalians a majority among Jews, ethnic Assyrians, Armenians, Greek Christians and Druze.

Maronite 0.8% (120,102)

While all the other Syriac Churches had a shared heritage through the Church of the East and Nestorian theology, the Maronites' beliefs and history were quite distinct. Indeed, the western dialect of Syraic they used as a liturgical language different from the eastern version used by the Nestorian-derived Churches. While the Maronite Church looked towards its origins in the third century monk Maron, they became theologically distinct in the eighth century through their adoption of the Christological doctrine of Monothelitism that held that while Christ had two natures, human and devine, he had but one will. With these theological disputes and following the Islamic conquest, the Maronites became isolated from the Roman Church, ingraining themselves as the core community in Mount Lebanon. For centuries the Maronites lived under the influence of outsiders – the Islamic Caliphate, the Seljuk Turks, the Crusaders, the Messalians who wrestled for control of the fertile Beqaa Valley, the Assyrians who conquered the wider Middle East and the Greek Christian elites who for centuries sought to dominate Assyrian Syria. Despite this, the Lebanese Maronites retained their independent religious and cultural identity.

Catholicism 25% (3,840,301)

With the annexation of Damietta in 1780, Catholicism went from a modest component of Assyria's religious mix to its second largest tradition, with a full quarter of the population following Rome's teachings. However, Catholicism in Assyria was notably different to its European counterpart. While in the West, the Church acted a monolithic entity that was centrally organised and offered the same Latin liturgy across countries and continents; in the Middle East it was a broader communion. Most Assyrian Catholics belonged to Eastern Catholic Churches, these were in full communion with Rome, accepted the sovereignty of the Pope, all Roman theological dogma and a shared Catholic identity, but retained locally distinct traditions, used separate liturgical languages and had partially autonomous local Church leaderships.

Coptic Catholic 16.4% (2,506,596)

The largest component of Assyrian Catholicism was also its most recent addition – the Coptic Catholics, the large majority of whom lived in Lower Egypt with notable minorities to the south in Upper Egypt, including both Copts and Nubians and the bulk of Egypt's modestly sized Black slave population. The Coptic Catholic Church was a major force, having more than half the number of adherents within the metropolitan Republic as the Church of the East itself and far more than any other religious denomination. As the faith of nearly four fifths of Copts, the Church was the dominant religious force in Lower Egypt and shaped the province's conservative outlook. The Church regarded itself as the direct descendant of the ancient Alexandrian Church founded by Mark the Evangelist, that had been the core of the later Coptic Church and Oriental Orthodox communion. It was in the aftermath of the Crusades that Church leaders in Alexandria were brought into full communion with Rome – the Coptic Pope being restyled as a Patriarch and accepting a junior role relative to Rome. This union brought almost the entire Church and Coptic community along with it. Even after the fall of the Crusader Kingdom of Egypt during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and Lower Egypt's domination by Assyria through he Duchy of Damietta, the Church remained a leading force in Lower Egyptian society and played a major role in resisting the region's annexation into Assyria in 1780.

Melkite Catholic 3.8% (588,300)

The Melkite Church was a creation of the Kingdom of Jerusalem during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. In the years after the initial Crusader conquest of the Holy Land, the new Latin landed elite began to look to Catholicise their new domain. As a first step, the clerics brought from Europe set about bringing the existing Christian communities – mostly adherents of Greek-rite Churches – under the authority of Rome. This marked the creation of the Melkite Church, which preserved the use of certain Greek religious rites and Arab customs while coming wholly under the authority of Rome and Catholic theological dogma. Over the centuries, the existence of the Melkite Church served as an additional distinction between the Latin ruling class and Arab masses of Philistia – while both were Catholic, they did not pray together. The greatest threat to the Melkite Church came with the Protestant Reformation, as preachers, many of whom had transmitted their ideas to the Middle East through Latin connections to Italy, rallied as much as a quarter of the Melkite flock to break away from the Mother Church.

Roman Catholic 2.5% (390,358)

Only a small part of Assyria's largest Catholic community adhered to the mainline Roman Catholic Church. The largest religious denomination in the world, with adherents across much of Western and Central Europe, the Middle East and New World, the Catholic Church was a sprawling entity of immense power. Growing out of the Roman Church in the West and at odds with the eastern Churches, Catholicism re-entered the Eastern Mediterranean during the Crusades, at the tip of Frankish, Italian and German swords who conquered large domains in Egypt, Palestine and the Red Sea. While the Crusaders had significant success in bringing many of the indigenous peoples of the East into Rome's light, they predominately did so through co-opting existing eastern Churches and bringing them into communion. Only the Latins themselves worshipped in Churches directly within the Roman Catholic episcopal structure. This divide served to accentuate the ethnic and social elite status of the Latin aristocracy – emphasising both their distinction from the native Copts and Arabs and aiding them in maintaining links to Europe. The other population within Assyria worshipping in mainline Catholic Churches were the people of Malta, who found themselves within the European Catholic mainstream – detached from the peculiarities of the Eastern Catholic Churches.

Cuman Catholic 2.3% (355,047)

The Cumans were a Turkic people who's exact origins in the endless lands of the Steppe are shrouded in mystery. They entered history when they supplanted the Jewish Khazars as the dominant force on the West Eurasian Steppe during the eleventh and twelfth centuries – in doing so pushing the Khazars to migrate to the southern shore of the Caspian, destabilising the Seljuk Empire and wider Middle East. Still pagan at this time, in the new Cuman Khaganate based on the Steppelands to the north of the Black and Caspian Sea, they were approached by missionaries from many lands and faiths. A Magyar Catholic named Istvan Tizva, with great knowledge of Turkic cultures and languages, ingratiated himself with their Khan and taught him of the greatness of God and the Roman Church. Tizva would play a large role in Cuman history – developing a written Cuman language for the first time used the Latin script. The Catholic missionaries allowed for some distinctive elements incorporating Turkic traditions and language into the Church they built on the Steppe. So distant from Rome, this degree of distinctiveness was tolerated by the Catholic Church, so long as the Cumans remained loyal to Roman authority, theology and hierarchy.

Cuman history took a dramatic turn in the thirteenth century with the arrival of the Mongols, who destroyed their Khanate and sought to eliminate Christianity on the Steppe. Those Cumans who resisted the demand to return to Paganism fled south, through the Caucasian Mountains and into the Byzantine and Assyrian Empires. The largest part of the Cuman population settled in Central Anatolia, where they built a Khanate centred on Ankara and pushed out the native Greeks. A smaller community unleashed debilitating raids against the Assyrians until King Nehor II came to terms with the Khan in 1257 and granted them lands on which to settle along his northern and eastern frontier in exchange for military service.

Thereafter, the Cumans, particularly in the Middle Ages, played a key role in Assyrian politics as the crown used them as a weapon with which to keep the nobility and external enemies in check. However, they were a frequently unreliable ally – most prominently during the Palestinian War of the early fourteenth century when they turned on King Niv II and, uniting with their king from Anatolia, temporarily captured Jerusalem for themselves. When peace was finally agreed, Niv had to surrender yet more land for Cuman settlement, this time in Philistia.

Through the centuries, they retained a famously militarist culture. All young Cuman men were expected to spend their youth in war bands or military service for the state before adopting the pastoralist lifestyle of their elders – always ready to take up the sword and bow again if need. They remained a key component of Assyria's armies, although this role eroded somewhat in the decades after the Revolution.

The Cumans within Assyria were divided between three populations: in Pontus they were the narrow majority, dominating the highlands and played a large role in the main city of Trabzon, while the Greeks lived on the coastal lowlands. In Philistia, they were as much as a tenth of the population – living mostly among their fellow Catholics west of the Jordan River. Finally, in Assyria-Superior, Cumans were around 5-10% of the population, with tribes scattered throughout the state, with greater concentrations in the mountains and especially on the shores of Lake Urmia near the Persian frontier.

Greek Christianity 11.9% (1,837,742)

The Greek-rite Churches were adherents of Byzantine Christianity its its different forms – traditional Eastern Orthodoxy, most commonly known as Old Orthodoxy, and the reformed Paulician variant that had ruled in Constantinople for centuries. Despite their sharp religious differences and heated relationship within the Byzantine Empire. The two main Greek Churches had traditionally cooperated closely within Assyria, protecting a shared Greek-influenced cultural corner of the nation from domination and encroachment from the Nestorians. Its adherents lived in many intermingled communities along the north-western fringe of the Federal Republic from the Caucasian Mountains to the Mediterranean Sea.

Old Orthodoxy 7.8% (1,202,211)

The Old Orthodox were the losers in the aftermath of the thirteenth century schism in Eastern Orthodoxy. Following the emergence of the Paulician reform movement, the Greek Church was irreparably divided between Paulicians and Reforms, sending the Byzantine Empire into nearly a century of endless religious conflict that brought the Empire to its knees and near destruction. This cycle of violence was only ended when Emperor Leo IX, a committed Paulician, defeated his enemies and reunified the Empire. Over the following centuries Old Orthodoxy was rooted out and regularly persecuted as successive Emperors sought to impose a Paulician ascendancy.

During the Early Modern period, Antioch replaced Constantinople as the central seat of the traditionalist Old Orthodox Communion, that also included autocephalous Churches in Armenia and Georgia that more nimbly catered to local national interests than the monolithic Paulician Church in Constantinople.

With Assyria, Old Orthodoxy was one of the Republic's largest religious currents and only grew more prominent with the country's territorial expansion in Armenia and the Caucuses during the Revolutionary Wars. Old Orthodoxy was the largest religion in Georgia, Western Armenia and in and around Antioch, while being a large force in Cilicia and to a lesser extent the rest of Syria.

Paulician Orthodoxy 4.1% (635,531)

Paulicianism was born in the thirteenth century as a reform movement within Eastern Orthodoxy – seeking a return to a more simplistic Church, modelled on Paul the Apostle. It drew some influences from earlier Iconoclastic movements, rejecting ostentatious displays of Church wealth, although not going so far as to advocate the removal or destruction of religious art and images. After emerging victorious in the ensuing Byzantine religious wars, the Paulician gradually asserted total dominance within the Empire.

One of the original heartlands of the Paulician movement had been Byzantine Syria, a territory that was lost to Assyria during Rome's period of internal conflict. Here, the Church, with its greatest powerbase around Aleppo – Syria's foremost city – remained strong and influential throughout the long centuries of Assyrian rule, acting as a key powerbroker within Syria. It maintained strong ties to Constantinople, often acting as a conduit for Byzantine influence. Elsewhere, Paulicians were relatively few in number in Western Armenia and Georgia, where Old Orthodoxy was stronger, but had more adherents in Cilcia, where the imprint of historic Byzantine rule had been stronger.

Islam 10.7% (1,637,301)

For seven centuries, the territories of the Assyrian Republic were the beating heart of the Islamic world. Damascus, Baghdad and Cairo had all been seats of great Caliphs. Jerusalem and Medina were second only to Mecca itself as Islam's holiest cities. Yet between the beginning of the twelfth and the end of the thirteenth centuries this dominion broke down in the face of the rise of Christian Assyria, a Byzantine resurgence and the Latin Crusades that saw Muslim temporal power retreat from Mesopotamia, the Levant and Egypt, never to return in its totality. This was a part of a wider crisis in Islam that saw it swept from Iberia and North Africa by the European, from the Caspian shore by the Jewish Khazars and from much of Central Asia and the Steppe by the Pagan Mongols while fracturing into different denominations and small states. From then, the Middle East had undergone a process of re-Christianisation that relegated the Muslim faith to a small minority current outside of Arabia, Oman and Upper Egypt. By 1817, the Church of the East alone had three times as many adherents as Islam, while there were almost nine Christians for every Muslim across the Republic.

Sunni Islam 7.6% (1,164,884)

Sunnism was the dominant form of Islam from the early days of the first Muslim Caliphates. It was defined through its emphasis of jurisprudence, the Quran and hadith and the authority of its Sharia courts. The Medieval Islamic crisis was an existential one for Sunnism – which saw the rise of major internal rivals in the Fatimid Shia and the Zikri in Persia and Mesopotamia alongside the wider advance of the Christian empires. The decline of Sunnism was halted only by the rise of Timur in the fourteenth century, who re-established Sunni dominance of Persia and the wider Islamic world, halted the long decline and even spread Sunni influence deeper into Central Asia and India.

Within Assyria, Sunnism was aggressively pursued by Christian proselytisers through the Middle Ages, to the extent that it had been largely pushed from Mesopotamia and the Levant by the beginning of the Renaissance and continued to face persecution, attempts at conversion, and unerring suspicion, often with good reason, that they were in hock with the Sunni Caliph in Arabia or the Timurid Khan in Persia. However, Sunnism's decline within Assyria was finally halted by two key factors. Firstly, many of the Bedouin tribes in Arabian interior proved too difficult and too independent, even for fellow Arabs from the Christian Gulf, for preachers to adequately reach. Secondly, Oman, a solidly Muslim country, grew to become centrally important to Assyria as its gateway to the Indian Ocean with rich connections to the many Muslim communities scattered from East Africa to India and the Indies. As a result, it was spared from any serious attempt at Christianisation in a barter aimed at maintaining the support of local elites. However the large majority of Assyrian Sunnism's demographic weight did not come from these numerically small Bedouin and Omani communities but from the 800,000 Egyptian Muslims whose homeland in Upper Egypt was annexed from the Sunni Caliphate at the beginning of the eighteenth century.

Shia Islam 1.9% (296,992)

The second largest branch of Islam both within Assyria and around the world, the Shia trace their origins to a dispute over the succession of the Prophet Muhammed. Always in the shadow of the dominant Sunnis, Shi'ism achieved its greatest influence during the High Middle Ages when the Fatimid Caliphate ruled over much of the heartland of the Islamic world in Egypt and the Levant. The Crusades and the rise of Assyria destroyed Fatimid power. Shi'ism only remained a religion of global significant owing to the remarkably rebirth of the Fatimid Caliphate in Ethiopia and Yemen from the fifteenth century onwards.

In Assyria, there were Shia communities scattered across a number of different areas. Small nomadic Arab Shia tribes occupied many of the deserts of Syria and Philistia, while the borderlands between Philistia and Arabia were predominantly Shia. In the Gulf, the island of Bahrain stood out as a Muslim spot in a Christian sea – its inhabitants being the only population to have successfully resisted the Christianisation of the region. Finally, and most importantly, there was Babylonia. While the Zikri outnumbered the Shia two to one across the wider province, the Shia were concentrated exclusively in the sacred shrine cities of Najaf and Karbala and the area around them. This area was the only part of Mesopotamia outwith Ilam without a Nestorian Christian majority, right in the heart of the most conservative Christian part of the Republic. Not only were Najaf and Karbala bastions of Islamic culture in the Republic's heartland, they were of incredible religious significance to Shia Muslims around the world – attracting thousands of pilgrims from East Africa and Yemen every year.

Zikri Islam 1.2% (175,425)

The smallest Muslim sect in Assyria, and the third largest in the world. Zikrism was significantly younger than the two larger branches of Islam. Originating in the twelfth century, during a period of crisis in the Islamic world that saw the birth of the Kingdom of Assyria, the Jewish Khazar migration to the Caspian and the Latin Crusades, their faith was founded by Hussein Zikrid a messianic and millenarian Islamic Mahdi. Mystical, open to outside philosophical ideas and hostile to the strictures of Sunni courts, the Zikri followed a distinctive version of Islam. Growing rapidly in the High Middle Ages, for a time it appeared destined to become the largest current of Islam – adopted in large numbers by the Kurds, becoming the plurality faith in Iran and also winning many followers in southern Mesopotamia. For a century after the collapse of the Seljuk Empire in the late thirteenth century the faith enjoyed a golden age, with a number of powerful Iranian polities adopting it as a state religion while in Assyria the Zikris enjoyed favourable treatment from the state compared to their fellow Muslims. Famously, or rather infamously, a Zikri even briefly sat upon the Assyrian throne when King Sabrisho converted as a young man under his Muslim mother's influence, before being murdered by his uncle Todos – the last of the sacred Qatwa dynasty.

Since then, the faith had endured a long and gruelling decline. In the east, the Sunni Timurids unleashed fierce persecution on the once religious diverse Iranian world – setting in place a steep decline of Zikrism in its heartland towards obscurity. In Assyria, the experience of Sabrisho soured Assyrian attitudes towards the Zikri, with efforts at conversion and occasional persecutions continuing for generations.

Despite this, by the nineteenth century Babylonia was the heartland of the small religious movement. Making up just over a tenth of the total population of the state, and most than half of the non-Christian free population, the Zikri were split between two main communities. In the east, the Ilamite Kurds were the majority population in their border territory and maintained close relations with their ethnic fellows across the border in the Timurid Empire – many of whom had held on to their Zikri religion even as the faith declined among the Persians. To the west, Zikri Arabs formed a large minority of the rural population along the Euphrates and Tigris in the region south of Baghdad and north of Basra.

Oriental Orthodoxy 7.6% (1,168,076)

Oriental Orthodoxy traced its origins to the Ecumenical Council of Chalcedon in 451, which marked the beginning of its split with the Roman Church, ironically only two decades after the adherents of its school of thought had been instrumental in the condemnation of Nestorius. Christologically, the Oriental Orthodox were the polar opposite of the Nestorians, believing that Christ was both fully divine and fully human in a single nature and revering Mary as Theotokos, or the God Bearer.

Internationally, the communion was a shadow of its once great self. At its peak, it was the main religion in Egypt, Armenia and Ethiopia and an important minority faith in the Levant. Yet history had not been kind to the Communion. By the nineteenth century, the Ethiopian Church had been relegated to a small minority by the ruling Shia Fatimid Caliphs while the Syrian branch of the communion had withered and died, largely absorbed into competitor Christian Churches. Indeed, by 1817, its community was largely confined within the borders of the Federal Republic itself where it formed only a small minority.

Armenian Apostolic 6.1% (934,062)

The overwhelming majority of Miaphysites were members of the Armenian Apostolic Church. Tracing its heritage to the very birth of Christianity in the first century, the contemporary Church actually had far more recent heritage. The original Church, with its unbroken history, was largely destroyed by the Byzantines during the High Middle Ages, who imposed Eastern Orthodoxy on the Armenian Church. After Armenia was ravaged by Mongol and Timurid invasions, the heroic figure of King Levon, the father of the great Aboulgharib I of Assyria, expelled the invaders and re-established an independent Kingdom of Armenia around Lake Van. A keen religious reformer, Levon re-established an independent Oriental Orthodox Apostolic Church that would quickly become the majority faith in eastern Armenia. For the next two centuries, the Apostolic Church enjoyed a golden age – winning outsized influence across Assyria with the rise of the Armenian Dynasty between 1426 and 1486 and retaining its special status as the ruling faith in the Kingdom of Armenia in the Federal Kingdom during the following century.

However, the Church never again regained a dominant position among the wider Armenian nation. Among communities that lived in western Armenia and Cilicia, which remained under Byzantine influence for far longer, Greek Christian denominations – both Old Orthodox and Paulician – resisted any advances while the long centuries of Assyrian rule saw a sizeable Nestorian minority emerge among the Armenians. In 1817, less than two fifths of all Armenians followed their purportedly national church.

Georgian Apostolic 1% (157,386)

The Georgian Apostolic Church traces its roots to the restoration of its Armenian mother church, with its own claim to apostolic succession being derived from its autocephaly from its more prestigious Armenian counterpart. For most of its history from its adoption of Christianity, Georgia had been an Eastern, rather than Oriental, Orthodox land. After the conquest of Georgia by King Levon at the beginning of the fifteenth century, the Armenians attempted to draw the Georgians into their re-founded Miaphysite Church. While these religious impositions resulted in rebellion and the loss of Georgia by the Armenians, an autocephalous Church under Armenian ecclesiastical authority was left behind and proved surprisingly durable. In 1817, more than a sixth of Georgians in Assyria were followers of the Church, most concentrated in the borderlands close to Armenia, even forming a majority in Tblisi itself.

Old Coptic 0.5% (76,628)

For most of its history, Egypt had been the heart of Oriental Orthodoxy. It was the Alexandrian school of theologians who first broke with the Roman Church, while Egypt long supplied the tradition's demographic weight and its most senior cleric – the Coptic Pope. It would be the return of Christian power to Egypt during the Medieval Crusades that eventually broke the religion that survived centuries of Muslim rule. In the Crusader Kingdom of Egypt, the ruling Latins co-opted the powerful Coptic Church, eventually bringing it into full communion with Rome. Only a small minority of Miaphysite clergy resisted this union, forming the Old Coptic Church that continued the old traditions with an ever diminishing number of adherents. Despite this, the Coptic Pope in Alexandria retained a special prestige among the wider Oriental Orthodox communion, where his seniority was recognised.

Protestant 5.4% (832,781)

Middle Eastern Protestantism was born out of the unique social tensions of Philistia and Egypt, societies created by the Crusades. In both countries, Catholicism was the main faith of both the indigenous masses and Latin elites who controlled much of society and defined the two realms in opposition to external enemies and rivals. Equally, those same elites connected these areas far more closely to European intellectual life than the rest of the Near East. Spiritual frustration within the Catholic world was rising from the end of the Medieval era, and Egypt itself hosted a precursor to later Protestant movements with the Ghalist revolt of the 1490s that saw Coptic Catholic reformers rail against Church hierarchies and Latin domination.

In the sixteenth century, the Reformation in its modern form arrived in the Middle East through the conduit of Latin Christians with connections to Italian Reformers. However Protestantism gained very limited traction among the Latins, instead finding a ready audience among the natives. The Coptic and Arabic Evangelical Churches, operating in close spiritual and political communion with one another, were formed and preached directly to the common folk in the vernacular. Under the reigns of Yeshua I and II, the Reformation in Philistia and Damietta was granted legal protection against the will of local Catholic powers as Nineveh viewed a means by which to loosen Rome's stranglehold on these realms. Winning over around a fifth of the Catholic population in both Lower Egypt and Philistia, the Protestants became powerful and influential even as they were unable to fully overcome Catholic pre-eminence.

Protected by the state and possessing a theological and cultural proclivity towards toil and investment, Protestant communities tended to thrive economically – with a distinct divide emerging between the relative prosperity of Protestant traders and peasants over their Catholic neighbours by the dawn of the nineteenth century.

Judaism 2.1% (322,770)

Assyria was the homeland of the Mizrahi Jews. They formed a highly urbanised, economically, commercially and politically influential and interconnected community from Egypt, through the Levant and Mesopotamia. Within Assyria, they were most numerous in the Republic's Mesopotamian heartland – more a tenth of the population of Baghdad, making one of the beating hearts of international Jewish culture, and slightly less than a tenth of the population in Nineveh while in most other major cities of Syria and Babylonia their numbers were around 5% or less of the urban population, and somewhat lower still in Egypt. In their spiritual homeland in Philistia, there were notable concentration in Jerusalem and just south of the city at Hebron to the west of the Dead Sea. Here, the community exerted extensive control over Jewish holy sites and pilgrimage.

The Middle Eastern Jews were distinct from their European counterparts. They had their own religious traditions and centres of scholarship, used a Mizrahi Hebrew dialect in their prayers, and were notably more integrated among their fellows. Indeed, Assyria's Jews spoke a dialect of Syriac and were free of any legal restraints. This followed a long history of relative tolerance for Jews in Assyria dating back to the earliest days of the Kingdom of Assyria. While this tolerance was the norm, it was not absolute. Assyrian Jews had faced their fair share of horrors – from the attempts of Messalian zealots to eliminate them in the thirteenth century to massacres by Lebarians during the Revolutionary Wars and even occasional efforts to impose Christianity upon them by proselytising preachers. Through all of this they had endured and flourished.

Druze 0.3% (52,115)

One of the very smallest communities within Assyria, the Druze were an esoteric sect that drew from Muslim, Christian and Ancient Greek philosophy in a genuinely unique religious blend. Originating in Fatimid Egypt in the eleventh century, where they elevated the sixth Fatimid Caliph to messianic status, the Druze were later forced to flee in the face of persecution – eventually settling in southern Syria. There, they formed tight knit communities, mostly in the Jabal al-Druze to the east of Damascus. Through the centuries they often had to fight for their survival in the face of efforts at conversion, both compelled and more peaceful, persecution from state actors and hostility from local rivals, notably the Messalians who lived to their west. Yet, for the most part their role in the history of the wider region was limited.

That was before the rise of their most famous son was undoubtedly Malik Abaya, the greatest of all Viziers who emerged from the chaos of the Revolutionary terror to stabilise the Federal Republic, end its civil war and conquer its external foes while reigning as Vizier for life for more than a quarter of a century. It was he who forged the Moderate coalition that would dominate the Republic for decades after his death, and his legacy still loomed larger over the Republic in 1817.

Although having benefited from fame and patronage during Malik Abaya's reign, the Druze remained a marginal community, almost exclusively living in their traditional homeland east of Damascus, with some living within the great city itself.

Madaeism 0.2% (34,699)

The smallest and perhaps the most unusual ethno-religious sect within the Republic were the Mandaean. Found largely in the swamps and marshes of Babylonia, with small communities in nearby major cities including Baghdad and Basra, the Mandaeans had scarcely features in the annals of Assyrian history. Revering John the Baptist as their highest prophet and practising regular baptism rituals in the sacred waters of the Tigris, according to their own traditions the Mandaean originated in Palestine and migrated to Mesopotamia at some point in the first of second century. Thereafter they lived in relative peace and isolation, being recognised as a People of the Book by the Muslims during their conquest and enjoying similar toleration under the Assyrians – who, as fellow speakers of a Syriac dialect, viewed them as distant kin. The sect was noted for its pacifism, forbidding members from carrying weapons and supporting obedience to the reigning political authority. With their small numbers and passivity, the Mandaeans had largely avoided great dramas and terrible disasters, all the while maintaining the continuity of their community and religion.

Ethnicity in Assyria

Purple - Assyrian

Light Purple - Assyrian Plurality

Green - Arab

Light Green - Arab Plurality

Yellow - Coptic

Mustard - Armenian

Turquoise - Georgian

Red - Greek

Pale - Cuman

Dark Blue - Druze

Light Blue - Kurd

Brown - Sudanese

Arabs 21.9% (3,382,869)

The largest single linguistic group within the Federal Republic were the Arabs, who made up a little over a fifth of the population. However, this group was incredibly ill-defined and diffuse – divided between distinct Arabic speaking populations with little in common in their geographies, histories, religion, national identities, social forms and levels of development beyond a shared language, albeit one with many different dialects. Indeed, even the distinction between Arab and other ethnicities was far from clear in many cases in which bi-lingual communities and overlapping religious, ethnic and national identifies muddied the waters.

Mashriqi 12.4% (1,901,241)

Mashriqi was a term used to refer to the Arabic speaking peoples of Mesopotamia and the Levant – in many ways the core of the wider Arab world. These populations were very close culturally to the Assyrians, and particularly in the case of Nestorians Arabs, identified very strong with the Assyrian state and a shared ethno-cultural heritage with the ethnic Assyrians. This shared Assyrian-Arab nationalism, often called Beth Nahrainism, was most powerful in Mesopotamia where there was little distinction between Arab and Assyrian other than language. Indeed, Syriac was very widely spoken among the Mashriqi as both a lingua franca and liturgical language.

Forming the majority of the population in Babylonia, Syria and Philistia, the Mashriqi were more distinguished by religion than their Arab language. In Mesopotamia, the Arabs were mostly Nestorians, although there were sizeable Zikri and Shia Arab minorities in Babylonia. In Philistia, the more populous lands west of the Jordan were largely Catholic, while east of the Jordan Nestorianism was the leading Arab faith. Syria was the most diverse Mashriqi region, with Arabs following half a dozen major Christian denominations. These different communities tended to identify most strongly with their particular sect, state and Assyria itself before any collective Arab nation.

Misri 5.4% (839,202)

For thousands of years of history, Egypt had operated as a cohesive national unit in a manner unseen almost anywhere else in the world. While the country passed from empire to empire, the Egyptians from the Delta to the Nile were always a distinctive people. The Islamic conquest of the seventh century set in motion the forces that would end that unity. Over six centuries of Muslim rule, the forces of Arabisation gradually undermined Egypt's Christian and Coptic character without ever truly eliminating it. This process was cut short and put into reverse by the Crusades – which ended Muslim rule permanently in the Delta of Lower Egypt and worked to expel any and all Arab influence from the land. While the Crusaders occasionally exerted influence further south into Upper Egypt, their power was always more fleeting and never permanent as Muslim states frequently established effective control over the region. This led to a divergence whereby Upper Egypt continued to Arabise and its majority population developed into the Sunni Muslim, Arab speaking Misri, while in Lower Egypt a Catholic and Coptic nation emerged.

Upper Egypt only became a part of Assyria at the beginning of the eighteenth century, a conquest of the Emperor Levon. Although initially hostile to Assyrian rule, the region and its people later became strong supporters of the Republic and the Moderate Ascendancy – seeing in Assyria a guard against the malevolent influence of the Copts and even producing the a Vizier from their community, Agbar Israel.

Bedouin 2.6% (402,376)

The indigenous populations of the Arabian and Syrian Deserts, the Bedouins occupied far more territory than any other people group within the Republic. Yet the constituted just a small portion of its wider population and an even lesser part of its economic life. Indeed, with the exception of a handful of urban centres – most importantly Medina – the Bedouins were largely desert dwelling nomads, moving with their herds of goats and camels between desolate lands and across vast distances. Much of the lands they inhabited in Arabia were essentially lawless. The state had only the faintest of imprints, with taxation and effective military control weak and inconsistent at best. These were peoples governed by tribal loyalties, continuous raiding, blood feuding and deeply held traditionalist religion – whether Sunni, Shia or Nestorian. Where they did interact with the state, it was largely in a transactional capacity – the government offering bribes to avoid disruption of trade and pilgrimage routes and using political intermediaries elected in the most dubious contests in the Republic, controlled by tribal elders to doll out state finance directly to these elites.

Maltese 0.8% (122,920)

Having only been annexed in 1795, in 1817 Malta had been Assyrian for a far shorter period than any other territory in the metropolitan Federal Republic. Its inhabitants spoke a unique language that mixed elements of Sicilian Italian, Greek and Arabic, professed the Roman Catholic faith and were comparatively wealthy relative to the rest of the Republic – having long been a centre of trade and piracy while also benefiting from European influences to adapt more modern economic practices even before the arrival of the Assyrians.

Omani 0.5% (83,047)

Although small in number, the Omani Arabs had played a significant role in Assyrian history, with the port of Muscat acting as a key gateway to the Indian Ocean – to the St Thomas Christians of Malabar, the riches of the East Indies, the slave markets of the Swahili Coast and the South African Cape. Its Muscati merchants had amassed incredible wealth, operating one of the largest slave markets in the world, while the city was also home to one of the most important bases of the Federal Navy. Meanwhile, Omanis had played a disproportionately large role in the Assyrian colonial empire from its birth. This wealth and strategic significance had aided the solidly Sunni Omanis in averting interference in their internal affairs, leaving Oman as the only part of metropolitan Assyria without a major Christian population, or any religious minorities of any type and allowing for greater religious involvement in the state locally than in any other province of the Republic.

Socotran 0.2% (34,093)

The island of Socotra, off the tip of the Horn of Africa was on the fringe between colonial and metropolitan Assyria. Home to one of the most ancient Nestorian communities in the world, the island came under the control of Assyria in the mid-fourteenth century and had remained a quiet and often forgotten corner of its realm ever since. Its only moments of significance had come during the early colonial period, when it acted as a staging post for expeditions into the Indian Ocean and experimentation in the slave-based colonial model exported to the Seychelles, Comoros and Mauritius. The Socotrans themselves spoke a dialect of Arabic, only outnumbered the Black slaves on their island by two to one and lived a life of insular seclusion.

Copts 21% (3,200,571)

The Coptic language is directly descended form the tongue of ancient Egypt, with Greek, Latin and Arabic influences shaping it over the course of the millennia. As such, the Coptic people viewed themselves as directly connected to this ancient past. The Coptic culture crystallised during the Hellenistic and Roman periods, and especially after the advent of Christianity and Egypt and the prestigious see of Alexandria emerged as one of the world's foremost Christian centres. The Coptic culture survived the Muslim conquest, even as the effects of Arabisation and Islamisation began to slowly take hold in Egypt over the next several centuries. This process was halted and reversed after the Crusades, as Egypt's Christian identity was reaffirmed and the Crusader elites consciously sought to drive out Arab and Muslim influence from their new Kingdom and brought the Coptic Church into full communion with Rome.

This period saw the emergence of the divide between the mostly Coptic and Christian north and Muslim and Arabic south of Egypt. The final demise of the Kingdom of Egypt in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries widened this cleavage further as Upper Egypt, under the rule of the Sunni Caliphs fell further into the Arab and Muslim orbit, while the Assyrian vassal of Damietta preserved a solidly Christian culture and anchored Lower Egypt to the wider Assyrian Empire.

The Copts formed a huge population that was far more cohesive and geographically concentrated than the diffuse and divided Arabic speaking peoples. In both Lower Egypt, where they were the large majority of the population, and Upper Egypt, where a Coptic minority still resisted total Arabisation, the Copts were predominantly lower class, mostly living as peasant farmers along the banks of the Nile and in the Delta. The exception to this trend were the large Protestant Coptic minority, who joined Jews and Assyrians as the basis of the Lower Egyptian middle classes. Given the dominance of the Latin upper class, the Coptic language itself had little prestige in Egypt and even less through the rest of Assyria, where Arabic and Syriac carried far more sway.

The interweaving of religious and ethnic conflicts and identities within Egypt led to a tension among Copts between two cultural axes: a Catholic Coptic identity, under heavy influence from Latin elites and hostile to the Protestants and other urban middle classes, and a broader Coptic ethnic identity that includes the Protestants and excluded the Latins. These alternate cultural axes were inescapable within

Assyrians 18% (2,766,600)

The core ethnic group of the state, around whose identity the Assyrian Kingdom, Empire and finally Federal Republic had been forged, the Assyrians had influence throughout the Middle East and world that defied their comparatively modest numbers. Although outnumbered by both Arabs and Copts, they carried tremendous cultural weight. The anchor of the Republic's leading faith – Nestorianism, possessing great historic prestige, disproportionately represented among the upper caste of many parts of the country, living in the most influential centres of culture and being the native speakers of the Republic's lingua franca – Syriac.

Ethnic definitions in the Middle East were notably porous and unclear. Many Arabs and Assyrians in particular consciously viewed one another as members of a shared Semitic race. Indeed, prior to the Muslim Conquest, the Middle East had been predominantly Syriac speaking while before the rise of Medieval Assyria, Arabic was much more widely spoken. Racially, the two populations were closely linked. The divides were further muddied by the intermixing of religion and language. Hundreds of thousands of Arabs, as adherents of Syraic-rite Churches, prayed in Syriac, many more had some degree of bi-bilingualism, even as they used Arabic in day-to-day life and were therefore defined as such in the census.

Nonetheless, this core Assyrian nation – Syriac speaking, exclusively Nestorian or members of splinter Churches – formed a majority in just a single state. This was the historic heartland of both Ancient Assyria and the Medieval Kingdom, Assyria-Superior in northern Mesopotamia, buttressed by the Zagros to the east, Euphrates to the west, Babylonia to the south and the Armenian highlands in the north. Even there, the Assyrians were only two thirds of the population, living among a cosmopolitan kaleidoscope.

Beyond this core state, Assyrian minorities were scattered across every corner of the Middle East. While making up a plurality in diverse Baghdad, across Babylonia as a whole, Armenia and Syria, Assyrians constituted 10-20% of the populations. Their portion was somewhat lower in Philistia and Arabia and lower still in Lower Egypt.

Armenians 16.2% (2,494,551)

One of the four pre-eminent national groups within the Republic, who combined made up three quarters of the population, the Armenians were among the most layered and storied groups. Their relationship with Assyria went back to the very beginning of Medieval Assyria, with Saint Ta'mhas the Great spending the last years of his life making war with Armenia over the religiously important city of Edessa. Thereafter, there was always a significant Armenian component to the Assyrian state, with Armenian polities serving as occasional friends and rivals in the following centuries. At the same time, with Armenia suffering brutal Byzantine, Mongol and Timurid conquests over the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, Assyria offered safe harbour to Christians fleeing into the Middle East, where they formed a thriving diaspora community in the cities of Mesopotamia and the Levant.

The interlocking of Armenia and Assyria only grew after the two nations entered into a union in 1438 under King Aboulgharib. The Armenian dynasty, established by the great King after the demise of the Qatwa in 1426, ruled Assyria until 1486 while two further ethnic Armenian Kings – Vassak I and II – ruled as a second short lived dynasty between 1520 and 1548. This era, a golden age for Assyria as a whole, saw ethnic Armenians establish a prominent place at the heart of Assyria that endured for decades. Indeed, the Kingdom of Armenia, dominated by the Oriental Orthodox elites of Van and Yerevan, enjoyed particularly great levels of centralisation. This extended to minting its own currency, the silver Drum, that was not lost until the eighteenth century.

While the prominence of Armenia declined somewhat from the end of the sixteenth century with parts of the country to the Byzantines, and its comparative economic decline owing to its inability to profit from trade and colonialism in the Indian Ocean; it would have a resurgence in the eighteenth century. Indeed, the city of Mus produced one of the most important minds of his or any other age – Yanai Babai, the founder of modern Liberalism whose disciples would form the Ishtar Club in 1725 and form the motor behind the Assyrian Revolution. During the Revolution, Armenia was the most radical of all provinces, a test bed for radical ideas – the first area to abolish slavery, institute mass suffrage and seek to establish a secular state. Thereafter, the country remained a bastion of left leaning liberal ideology. Importantly, the Revolutionary era also saw the entirety of the Armenian homeland from Cilicia to the Caucasian Mountains fall under exclusive Assyrian rule for the first time, leaving the large majority of the world's Armenians within the boundaries of the Federal Republic.

The Armenian ethnos was split between a number of key religious and geographic subdivisions. Eastern Armenia, based around Lake Van and Yerevan, with the longest unbroken lineage of Assyrian rule had been the traditional heartland and centre of power within Armenia. Its population was majority Oriental Orthodox, with a sizeable Nestorian minority of both Assyrians and ethnic Armenian Nestorians.

Western Armenia stretched across the historic borderlands between Assyria and Byzantium. While there were Oriental Orthodox and a, smaller, Nestorian presence here, the majority followed the Old Orthodox branch of the Armenian Church. Indeed, with Greek and Assyrian influence colliding and a long history of relatively weak government structures owing to perennial raiding by the Cumans of Central Anatolia, Western Armenia had effectively provided a safe haven for a religious community seeking shelter from Constantinople, Van and Nineveh alike.

On western fringe of the state of Armenia was Cilicia, where Byzantine influence was strongest. There were few Nestorians or Assyrians and a mixed population of Greeks and Armenians, Paulicians and Old Orthodox. At the same time, all three sectors of the Armenian state bled into Syria and Assyria-Superior to the south – with large Armenian minorities found across the borderlands with large presences around cities including Edessa, Amid, Aleppo and Antioch.

Further afield, an Armenian diaspora could be found as a largely middle class, affluent and urbanised minority across the cities of Mesopotamia and the Levant, with particular strength among artisanal manufacturing guilds.

Georgians 5.8% (894,534)

The intertwining of Assyrian and Georgian history began during the reign of Levon of Armenia, the father of Aboulgharib. While he conquered Georgia and later lost control of it, he retained a claim to its Kingship the was passed on to his son when he united Armenia and Assyria in 1438. Under the resulting Armenian dynasty, Assyria attempted to exert control over parts of Georgia – notably around Kars and Kartil. Most of these lands were lost at the end of the sixteenth century in the midst of the fall of the Federal Kingdom. Assyrian power remained absent from all but a tiny enclave of Georgia until the end of the Great Persian War two centuries later, which saw a larger part of the country fall under Nineveh's control than ever before in history. Assyrian Georgia included the largest Georgian city in Tblisis and stretched westward to Kars and then the Black Sea coast Batumi, featuring all the most important cities of the Georgian nation.

While ethnically homogeneous, the region was fairly religiously diverse. Tblisi and the eastern part of the country was heavily influence by Armenia and Oriental Orthodoxy held sway as the largest faith, but only by a small majority. Through the rest of the country, Greek-rite Churches were stronger, with a significant Paulician minority that was especially strong along the coast, being outnumbered by adherents to Old Orthodoxy.

Blacks 3.9% (595,000)

There was no people in all of Assyria so wretched, abused and downtrodden as the Blacks. With no single ethnic identity or origin, the Blacks were the descendants of slaves brought to the Middle East from the Swahili Coast of East Africa, or Zanj as the Arab's called it. However many traced their origins from all over Africa, with Swahili slavers driving deep into the interior and often raiding the island of Madagascar to fuel demand. In the Middle East, these distinctive identities were largely destroyed under the weight of the whip hands of their masters – defined solely as Blacks and largely regarded as sub-humans by their Middle Eastern masters.

Only a small minority, legally obliged to reside within impoverished, decaying and crime-ridden ghettos in the cities of Syria and Assyria-Superior, were not bound by slavery. Most lived in the southern portion of the Republic, where slavery had survived the Revolution and remained firmly in place. They made up their largest portion of the population in Muscat – alongside Basra, among the largest slave markets in the world – and Socotra where they formed a third of the population. Through the rest of Oman, Black slaves were around 20% of the population, 10-20% in Arabia with larger concentrations around Medina and the Gulf Coast, with their numerically largest concentration in Babylonia where they were around 15% and worked in intensive plantation agriculture - more than a quarter million souls. In Egypt, the last of slave states, they were a far smaller portion of the population and a much less important part of the wider economic structure, yet they still numbered in the hundreds of thousands there. Their numbers had ebbed and flowed over the centuries, and by 1817 were somewhat lower than they had been at their peak a century. Nonetheless, even at the dawn of the nineteenth century, thousands of slaves were imported into the metropolitan Republic every year – adding to the Blacks' numbers.

Kurds 3.3% (507,210)

The Kurdish nation was cleaved into two quite distinct populations – the West Kurds and the East Kurds, broadly divided geographically by the Zagros Mountains and culturally by dialect, religion and history.

The majority of Kurds living in Assyria were West Kurds, who inhabited the northern and eastern fringes of Assyria-Superior, where they ranged from a quarter to a third of the population, while also having Kurdish Quarters in major Mesopotamian cities including Nineveh, Samarra and Baghdad. While having major urban centres in Amid, Arbil and Kirkuk, the West Kurds were predominantly pastoralists and many lived a tribal lifestyle in the highlands. Having been a major antagonist of Saint Ta'mhas the Great during the formation of the Kingdom of Assyria in the twelfth century, the West Kurds had been largely under Nineveh's rule since the early days of the Assyrian state and endured centuries of Christianisation and Assyrianisation. As such, they were exclusively Nestorian Christians and over the generations many had abandoned the Kurdish language and identity and assimilated into the Assyrian ethnos while those that remained spoke a dialect with significant Syriac influences. While at times wild, the West Kurds were seen as a core part of Assyrian society.

The East Kurds were quite different. Much more numerous than the West Kurds, they formed the majority across a stretch of territory east of the Zagros that lay predominantly within the Timurid Empire but also stretched to Ilam in eastern Babylonia. Their dialect and culture was more Persianised and they had held firm to their Islamic faith – with Zikri Islam remaining popular, in particular with Assyria's Ilamite Kurds.

Greeks 2.7% (418,064)

Greek language and culture had significant sway in Assyria. The Greek-rite Orthodox faiths were the predominant religion of the north-western fringe of the Republic stretching from Georgia to Latakia and had traditionally been the dominant element in Syrian political life while Greek was also used regularly among the Levantine Catholic Melkite Church in Philistia. Further to this, the language held international prestige as a major language of diplomacy, science, culture and history. Indeed, Greek challenged Syriac, Arabic, Coptic and Armenian as one of the most commonly used throughout the Republic.

However, the ethnic Greek, or as they preferred to describe themselves – Roman, was much smaller, standing at just over 400,000. The centre of both the ethnic Greek community and the wider culture was the sacred city of Antioch – one of the Roman pentarchic patriarchal seats and influential centre of religious scholarship and leadership. There, the Greeks formed a plurality in a highly diverse city that was also home to many Arabs, Assyrians, Armenians and Jews. Elsewhere, the Greeks were around a third of the population in Cilicia, as much as two fifths in Pontus – where they farmed the coastal plains while the Cumans lived in the highlands, and formed a smaller portion of the population across northern and western Syria. Religiously, the Greeks were a mix of Paulicians – especially in Pontus and Cilicia, and Old Orthodox. Antioch in particular, that had been under Assyrian rule since the Middle Ages, retained a tempestuous relationship with Byzantium to the west, often a gateway for pro-Byzantine elements within Assyria while also harbouring many dissidents escaping Roman persecution, which was why it had attracted such a large Old Orthodox community.

Cumans 2.3% (355,047)

See religion section.

Jews 2.1% (322,770)

See religion section.

Latins 1.7% (267,438)

The Latins were an ethnically distinct ruling class inhabiting Philistia west of the Jordan River, Lower Egypt, parts of Lebanon in Syria and the north west of Arabia around Tabuk. As the descendants of the Crusaders who had come to Outremer to establish a series of Latin Catholic polities in the Middle Ages, they formed the aristocratic elite throughout these territories and as such had played a very prominent role in the histories of these lands for several centuries. Ethnically, they were drawn from across Europe, with particularly large Italian, German and French components but had evolved, quite uniquely, to use Latin as their primary language after centuries of employing it as a lingua franca within their comminity.

Despite achieving significant success in bringing Arabs and Copts in Philistia and Egypt respectively into the Catholic Church, the Latins retained a clear social and ethnic distinction from the wider populace in the lands in which they lived, often turning towards Europe for marriages with fellow noble lineages, and to a lesser extent the wider Middle Eastern aristocracy. Despite the ructions of the Revolution, the Latins had maintained their social standing, lands, and in Egypt their slaves, to a much greater extent that their fellows in Syria, Assyria-Superior and Armenia, even as the advent of an electoral franchise that extended significantly beyond their numbers challenged their leadership of the Catholic communities of Assyria.

Druze 0.3% (52,115)

See religion section.

Persians 0.3% (48,618)

The Persians were one of the smallest ethnic communities in Assyria. They lived scattered along the coast of the Persian Gulf, with their main concentrations in Muscat, Basra, Bahrain, the Trucial Coast and by the Strait of Hormuz. Universally, they occupied a niche as merchants focussed on trade with the Timurid Empire, where they enjoyed a slight advantage of their Arab, Assyrian and Jewish competitors owing to their kinsmen's preference for dealing with fellow Persians over foreigners. Religiously, they were a solidly Muslim community, mostly Sunni but with some Zikri and Shia minorities.

Nubians 0.3% (48,080)

Although black Africans themselves, the Nubians were considered to be distinct from the Blacks within Assyria. Unlike the Blacks, they were not of foreign slave origin but had lived for centuries to the south of Egypt and as such enjoyed a higher social standing. Like the Copts, they were a Christian people who worshipped under the Coptic Catholic Church, although increasingly under pressure from the Islamising influence of the Fatimids to the south. Within Assyria they were found only in very small numbers on the southern fringe of Upper Egypt, even forming a majority in the south eastern corner of the region.

Mandaean 0.2% (34,699)

See religion section.