TWO: TONNERRES (January-June 1936)

German troops being welcomed into the Rhineland

7 March 1936

The French ambassador to Germany, Andre Francois-Poncet, was hunched over a telephone inside a room of the Palais Beauvyre. His eyebrows were furrowed, his fingers continually dancing over the stack of papers in front of him. Needless to say, Baron von Neurath’s message had been unexpected. Lebrun’s reaction would not.

“Monsieur President, there is no room to conduct negotiations. Their battalions are halfway to the Rhine. Any further effort will be viewed as desperate appeasement.”

Lebrun was fuming. “What else can we do? Call up the army? You know well Gamelin will never mobilize a single man until Britain does.”

“Force is the only means necessary.”

“Our neutrality is too high. Even hopes of Hitler being deposed will not sway them.”

“Do you want this… circus to continue? We can finish this, right here.”

“Invading Germany will only make us the aggressors. Hitler has not declared war on anyone.”

“Monsieur, you don’t understand. Now he doesn’t have to!”

Andre heard silence, thought for a moment it was over. He felt again that sinking as he read the paper. Across the border… into the quicksand. Might as well pack his bags.

Lebrun was talking, slowly. “Do you want me to relieve Gamelin?”

“Monsieur, I… am hardly qualified—“

“Listen, ambassador! Do you think that, to have a stronger stance, new leadership is necessary?”

Andre stood still. True, Gamelin was a man of the people. Removing him like this, it wasn’t right. There would be consequences. And yet…

“Only a lion can fight another one, president. I will… leave the decision to you.”

Lebrun sighed, a touch of sarcasm in his voice.

“You are right, Andre. Change is necessary. Return to Paris at once, and your letter of resignation with you.”

For a moment Andre was too startled to speak. There was no one on the other line, not even a single ending word. He quietly set down the telephone, folded up the papers, and went to his room.

_____________________________________________________

The news of Germany’s reoccupation of the Rhineland struck many chords throughout Europe. Italy and Japan drifted even closer to the Axis, spurred by France’s inaction. Germany itself received much-needed industry and a prestige boost. Hitler had publicly violated the Versailles Treaty in 1935, but now decisive action had been taken. Now the stage had been set for war, for another Schlieffen. Soldiers patrolling the Maginot Line could now see German supply trucks and artillery in the Palatinate. Further escalation of Germany’s threat was inevitable.

Andre Francois-Poncet did return to Paris, and was replaced by Robert Coulondre. The day before he left Andre had delivered an ultimatum to von Neurath to immediately remove all German troops from the Rhineland. Unfortunately, the old baron saw through the bluff and realized Andre was acting alone with no authority. Once at home, Lebrun chastised the noble diplomat and threatened to prevent his ever holding another office again. Even absolute secrecy did not prevent this news from being leaked. In the aftermath of the May election, Andre was reappointed as ambassador to Germany and lauded as a hero. Whether his advice would be heeded, however, remained to be seen.

The Low Countries continually rebuffed every attempt for military access. An anti-war demonstration in Brussels in June attracted thousands. Leopold III still made only vague promises of aid. His ministers opposed his plans and rallied the legislature behind neutrality. Clearly, France could not depend on Belgium. This sense of mutual suspicion was heightened by an anonymous letter published in the Brussels papers.

“Why do we Belgians continue to trust the French? They did not help us in 1914, and they will not help us again. Their government has been invaded by despicable Communists. Their army is commanded by lazy despots that resist change. We are better than them. We do not need them to drag us into a war we will surely lose, our beloved country occupied and in even worse conditions than the Great War. Belgium must remain free, entangling alliances with no one. If France continues to pressure for access, if France continues to violate our neutrality, then they are no better than Kaiser Wilhelm.”

Letters such as the above reappeared in certain gazettes for years, and certainly had at least some influence. It would not be revealed who the anonymous writer was until after the war. A German spy by the name of Alex Bordmann had set up an espionage ring in Antwerp, hiding political messages from government contacts in his editorials. Bordmann had attempted to stow away aboard a convoy to Sweden once war was declared, but he was seized by Belgian police and his remaining papers classified until recently.

In early May, urgent news reached Paris—Italian forces under Pietro Badoglio had entered Addis Ababa. A few Ethiopians retreated into Sudan and Kenya, refusing to lay down their arms, but for all practical purposes the Abyssinia Affair had come to a close. Emperor Haile Selassie fled through French Djibouti to England. Before the League of Nations in Geneva, he gave a stirring speech. “It is us today,” Selassie said. “It will be you tomorrow.” Featured on newsreels around Europe, it shocked many. Some denounced it as sensational nonsense. After all, Italy was just as weak as France. Any budding intentions Mussolini had would be “killed in the shell” by the Allies. The League of Nations refused to help Selassie. On the contrary, in July, they lifted their sanctions on Italy. No one mentioned the Italian bombing of Red Cross tents in Ethiopia, a clear war crimes violation.

The news was not a surprise

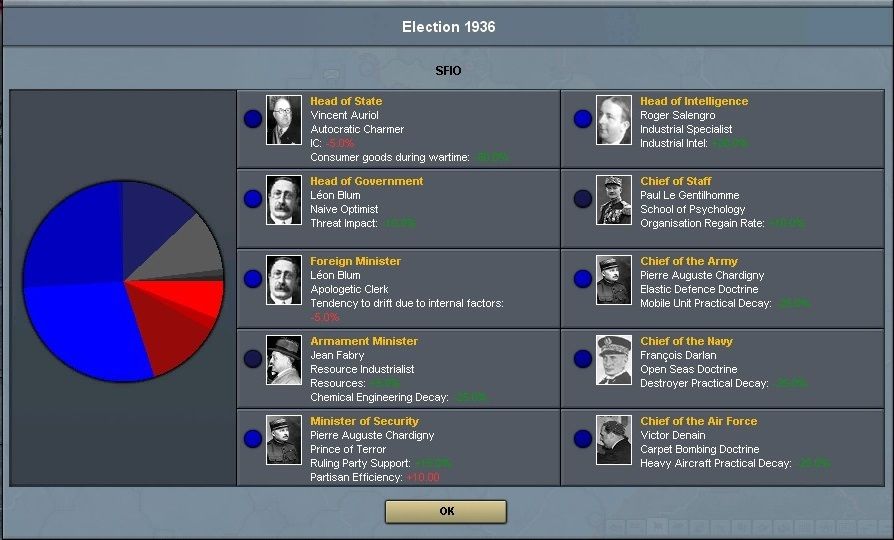

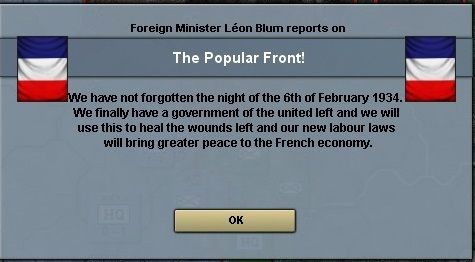

On 4 May, the election results filtered in. Vincent Auriol of the SFIO (Section Française de l'Internationale Ouvrière), or French Socialist Worker’s Party, emerged as the new head of state. While lowering IC by 5%, he also lowered consumer good needs during wartime. For many, the election spelled the end of French democracy. In 1934 the SFIO had signed a pact of unity with the French Communist Party. Now their Popular Front was growing almost beyond control. Yes, they had driven back any Fascist influence, but was that better or worse? What chains would France now be forced to bear? In June, the Popular Front proclaimed “a new era for France”, gaining 6 unity and 35 money. These would be critical to lower neutrality and pass more efficient laws. And yet, the people still grumbled.

Only time will tell how effective the Auriol government will be

Auriol’s triumph led to new negotiations with the Soviets. A defensive pact between the two nations had been signed in 1935, but the SFIO wanted a full alliance. Rumors flew—Maxim Litvinov, the Russian foreign minister, was seen with Auriol at a concert. Leaked correspondence told of an official meeting in Strasbourg, of Russian planes landing at Paris airfields. Gamelin and High Command adamantly rejected these claims, and, as usual, the alliance came to naught. Litvinov had indeed come to Paris, but only for a few days. Faced with a rioting public and a rotting army, he’d left for Moscow with no high expectations. An alliance was simply out of the question for at least a few more years.

Maxim Litvinov, USSR foreign minister

In the area of military, the three corps pulled from Syria and Africa were beginning to be organized. One corps, the news Corps de Toulouse, was sent to guard the Spanish border. This assignment would soon prove fortunate. The other two corps remained in the Cote d’Azur as reserves for the Southern Theater. Eventually these would be upgraded to mountain divisions and put into the Alpine defenses. Of especial note were the Algerian divisions. Many hoped the presence and help of colonial troops would later promote peaceful North African independence.

Algerian troops arriving in Marseille

However, one general was not pleased with the transport of the Algerians- Maxime Weygand. Head commander in Africa, the renewed focus on the homeland came as a rude awakening to one who’d always stressed North Africa’s importance in any future war. Only one corps remained in Tunis, barely enough to garrison Tunisia, much less launch an offensive into Libya. Weygand’s pleas to return his troops went unheeded. Instead, Gamelin appeased Weygand by offering him a key position in the new Army Group Belgium. Weygand grudgingly accepted and arrived in Paris in April. Henri Giraud replaced him in Africa.

Weygand at his new office in Lille

The best of France was now unified in one focus- Germany. Together, Weygand, Gamelin and Georges would defeat the Wehrmacht. They would quell the bitterness and restore France to its old glory, to its old sons. And yet, there was that small hint of more thunderclouds. More lightning strikes. A rift was rapidly growing in High Command, between the daring and the weak, the veterans and the young. Blitzkrieg was coming. It would test them all. It would decide for them all.