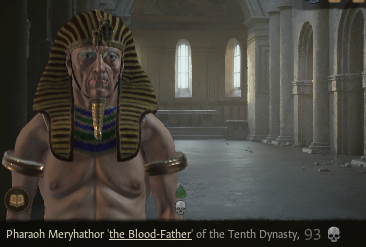

Merenre III (Reign:

2060-2062 BCE) ascended the throne with vigour and purpose, a striking contrast to his father, Neferkare II, whose reign, though victorious, had been marked by illness and the shadow of death. The new pharaoh was in the prime of his life: strong-willed, sharp-minded, and charismatic. His coronation reflected this energy, grand, extravagant, and rich in symbolism, declaring a new chapter in Egypt’s divine kingship. It was not vanity or defiance. Merenre had loved his father dearly. But he understood what few rulers truly did: that power is not merely possessed but must also be seen. And a strong image of the throne was vital for an empire surrounded by predators.

Unlike his war-hardened grandfather and iron-willed but frail father, Merenre was no stranger to battle. He had stood among the smoke of burning cities, tasted both triumph and loss and walked among the corpses of friend and foe alike. These experiences did not harden him; they humbled him.

The hieroglyphs etched into the walls of Karnak, Luxor, and Abydos speak of a surprising truth: Merenre III, though a brilliant general, despised war, not out of fear but because he understood its cost.

“War is the tax a nation pays when it fails to speak wisely,” he once said.

“But when it must be paid, let Egypt pay in gold, not in sons.”

The early years of his reign were filled with reform and prosperity. He reorganized the army into streamlined battalion divisions, professionalizing what had once been a semi-feudal force. He funded vast public works, temples to appease the gods, canals to water the land, granaries to secure the future, and roads to unite the country. Egypt flourished. It was a time of light.

But in his heart, Merenre carried darkness.

His marriage to Princess Meret had given him joy and four daughters, but it was the birth of their only son, named Neferkare in honour of his grandfather, that had seemed to complete his world. Then, within days, it collapsed. Meret died in childbirth, and Merenre, overwhelmed with grief, never took another wife. Instead, he commissioned an immense tomb for them both, carved high into the cliffs near Waset, where the sun’s first light would forever kiss her resting place. From that day forward, something inside him never truly returned to him.

And while the king mourned, the world burned.

To the north, King Zuwa of Hatti fell, and his ambitious son Summiri seized power in a brutal five-year civil war. In the east, Empress Abdosir of Hurri held her throne with cunning, while the Sumerian warlord Enana Bily II united his realm under an iron fist. Then came the shock: Sumer and Hurri, age-old rivals, signed a treaty of alliance. The great powers of the known world had split into two poles: Egypt and Hatti on one side, Sumer and Hurri on the other. A cold war had begun.

Merenre understood the stakes. Canaan, fragmented and strategically vital, was the battleground between empires. Though weary of war, he knew Egypt could not afford passivity. He declared war not upon foreign empires but on the last independent provinces of Canaan. He did not take the field himself, entrusting command to his brilliant uncle, Prince Wadjmose, known as

The Wolf of the West. Merenre remained in Memphis, ensuring the state ran smoothly and the gods remained favourable.

By the sixth year of the war, most of Canaan lay under Egyptian banners. Only a handful of fortified cities, propped up by Hurrian silver and Sumerian arms, held out. Victory was in sight. But peace was an illusion.

Reports arrived in Memphis of a secret Hurrian envoy received in Sumer, followed weeks later by the shocking news that Hurri and Sumer had launched a surprise joint offensive against Hatti. The Hittite cities of Tarhuntassa and Zippalanda burned. Messengers from Hatti flooded Memphis, begging for support. Egypt’s advisors panicked, fearing that a Sumer-Hurri axis, unopposed, would soon turn its gaze toward the Nile.

But Merenre did not move.

He had grown quiet in recent years, lost in grief and retreating from the world he once ruled with clarity. He spent his days playing senet, surrounded by his grandchildren, drinking wine beneath the painted ceilings of his palace. The fire that had once driven Egypt forward now flickered low.

It was then that Prince Kheti, the king’s uncle and chancellor —a man born to a concubine but elevated by merit —took action. According to the

Chronicles of the West Wall, Kheti stood before the pharaoh and said:

“You were born to guard the Two Lands, not watch them drown in foreign shadows. If you do nothing, Egypt will fall not today but in the years to come. Your father would never have allowed this. Your son must not inherit a kingdom already half-lost.”

Merenre said nothing. But the next morning, he emerged from the palace in full regalia.

He summoned the scribes, signed a formal treaty of friendship and alliance with Hatti, called up the army reserves, and gave Prince Wadjmose command of the Egyptian war machine. He declared war on Sumer and Hurri, stating:

“Let them learn that Egypt sleeps only when it chooses. And when she wakes, the world trembles.”

The gears of war began to turn once more. Wadjmose was dispatched eastward, with the elite Black Falcons and Gold Spear divisions at his side. Egyptian spies infiltrated Hurrian outposts. Ships were sent to aid the Hittites at Byblos and Ugarit. Even the temples began to churn out war hymns once again, invoking Sekhmet’s fury and Montu’s wrath.

But in Memphis, the aged Merenre watched the sunrise from the steps of his wife’s tomb, knowing that whatever victories came, they would be for others to enjoy.

Prince Wadjmose, Pharaoh Merenre III’s uncle and generalissimo, was feared and revered as

The Wolf of the West. In his youth, Wadjmose had led brutal raids against the Libyan confederacies, earning his nickname through swift, ruthless strikes and a mind sharpened not just for battle but for psychological warfare. Now, in the final decade of his life, his frame had thickened and his hair grayed, but his instincts had not dulled. He remained Egypt’s most dangerous weapon.

His army was not the ragtag host of generations past. Merenre’s reforms had given him a professional force of career soldiers organized into standardized battalions. Under his command were the

Black Falcons, Egypt’s elite archer corps drawn from the Delta marshes; the

Gold Spear Guard, veterans from the Canaanite campaigns clad in bronze-scaled armour; and the newly formed

Chariot Corps of Sekhmet, agile and lethal units trained to fight in mountainous terrain.

Wadjmose’s campaign began with swift movement.

Rather than reinforce Hatti directly, where the front lines were already in chaos, he launched a flanking invasion from the southeast, striking at the Hurri-controlled city of Qadesh. Qadesh had long been a thorn in Egypt’s side, its allegiance bought and sold between empires like a merchant’s trinket. This time, there would be no negotiations. After a three-week siege, Egyptian sappers undermined the walls, and Wadjmose ordered a full assault. The city fell, its defenders put to the sword. The Wolf had made his opening statement: Egypt had returned.

From there, Wadjmose advanced swiftly north through the Levant, retaking old vassal states and cutting off Hurrian supply lines that fed their armies further west. Every conquered city was left intact but taxed. Wadjmose understood the value of both fear and loyalty.

“Crush their pride,” he wrote in one of his campaign dispatches,

“but leave their granaries full. Let them eat bread under Egyptian banners and learn the taste of discipline.”

Near the plains of Arpad, Wadjmose faced his first significant resistance: a Hurrian-Sumerian coalition under

General Atar-Mal, one of Abdosir’s most ruthless protégés. Their forces met in a pitched battle under heavy rain, a rare weather phenomenon interpreted by both sides as a divine omen of disapproval.

The

Battle of Arpad lasted two full days.

Hurri-Sumerian infantry, bristling with pikes and war axes, surged forward with terrifying discipline. Wadjmose outnumbered and at risk of encirclement, executed a daring night maneuver: he ordered the Chariot Corps of Sekhmet to circle the enemy camp under cover of darkness. By dawn, as Atar-Mal prepared for a renewed assault, the Egyptian chariots struck his rear lines in a thunderous charge. Chaos erupted. Atar-Mal was killed in the melee, and the coalition army was shattered.

It was a costly but decisive victory.

With Arpad secured and the Sumerian general dead, Wadjmose pushed further into Hurrian-held territory. For the first time in over a generation, Egyptian banners flew near the Euphrates. The symbolic significance of this advance cannot be overstated. It had been nearly a century since an Egyptian army had approached the river-god’s waters. Now, it was Wadjmose who stood there, drinking its cool currents from a bronze cup.

But with every mile gained, resistance hardened.

Empress Abdosir had not been idle. In response to Wadjmose’s advance, she ordered the conscription of thousands, summoned her mountain allies, and sent gold to Sumer for the hiring of mercenaries. Word reached Wadjmose that

a massive Hurri-Sumerian counteroffensive was forming beyond the mountains, near

Kummukh, led by Abdosir herself.

Rather than retreat or dig in, Wadjmose chose to bait them.

He withdrew southward, appearing to abandon his conquests and retreat to Qadesh. In reality, it was a feint. His men razed bridges, salted fields, and laid false trails—drawing the Hurri-Sumerian army into exposed terrain. Then, at

Tell Zarim, where the hills dipped into a long plain, he struck.

The battle lasted only four hours.

It was a slaughter.

Caught in the open, harried by arrows, and flanked by chariots hidden in ravines, the Hurri-Sumerian army collapsed under the weight of Egyptian tactics. Thousands were killed. Dozens of Hurrian nobles were captured alive and paraded through Qadesh in chains. Wadjmose, to the shock of his officers, spared them.

“Tell your empress,” he said,

"“that Egypt does not need slaves—only silence."

Back in Memphis, word of Wadjmose’s victories spread like fire.

The temples proclaimed it divine justice. The people celebrated in the streets. And for the first time in years,

Pharaoh Merenre III emerged from mourning and returned to the Temple of Amun, offering a hundred oxen in gratitude. His son,

Prince Neferkare, now a young man, stood beside him, watching the flames rise.

But Merenre knew what his uncle did not: that every victory awakens new threats.

In the east, Empress Abdosir was already retreating to her capital, wounded, yes, but not defeated. Sumer had suffered less, and whispers of a new general—

Ningal-Tur, called the “scorpion of the South" reached the ears of Egyptian spies.

Even more concerning,

trouble brewed in Nubia, where gold shipments from the south had ceased, and tribal leaders were gathering.

The war was far from over.

And as Prince Wadjmose stood victorious over Canaan and the eastern marches, the Wolf of the West now stared across the horizon toward the final crucible—the very heartlands of Hurri and Sumer. And somewhere in that distant east, Abdosir sharpened her vengeance.

However, Merenre would not live to see the end of the war; he died of illness at the age of 77. His son, Neferkare III, would have to see it through to its end.