Chapter 2: The Winds of War

5 May 1088

The olives and grapes in the Ionian Islands were budding when Alexios I Komnenos announced the completion of his monetary reforms. Never a man for rest, the emperor invited his strategoi to discuss potential war targets. Chief amongst the doux was Isaakios Kontostephanos, whom the Basileus entrusted with the post of marshal.

Between the jingoist border strategoi and the peace-inclined island doux, the council agreed that the best target to attack was the principality of Rascia. It was de jure Roman territory historically, and the self-proclaimed ‘King’ Vukan of Diokleia flaunted his independence in the face of his mightier neighbours. It was time to take back what was rightfully Byzantine, and give the other Balkan lords a lesson. Isaakios rode home to Epirus to muster his own cataphracts before joining the Imperial Army.

Isaakios led the centre column in the siege of Rascia. The Prince of Diokleia wisely manoeuvred his troops into Byzantine territory to avoid a pitched battle, which would have surely resulted in a crushing Byzantine victory. In a few weeks, the Byzantine army made short work of Rascia Castle, and Isaakios was prepared to order the troops to occupy the neighbouring town and monastery when a runner delivered an unfortunate message.

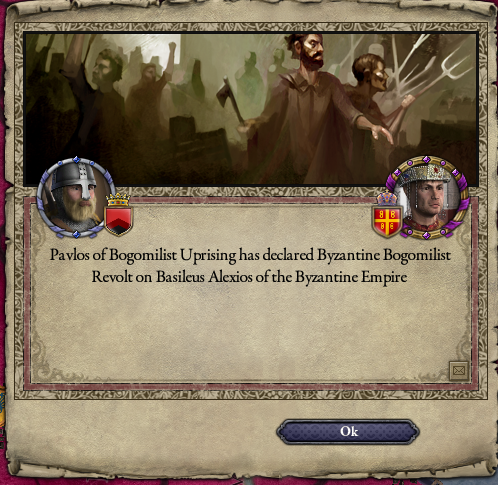

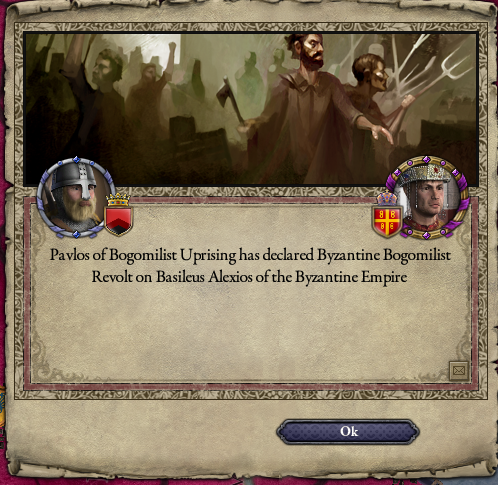

Emperor John I Tzimiskes had welcomed over 100,000 Armenians into the empire under his reign a century ago. Most of them had settled in the Bulgarian and Macedonian themes, and some of their communities were within a few days’ march of the main Byzantine force. It seemed that the foreign Prince had stirred discontent and encouraged heresy with his spies in Macedonia in preparation for just such a war. With the prospect of facing a united enemy of Diokleia and Pavlos’ heretics, Isaakios worried the Empire would suffer more losses than expected. He sent word to Alexios and ordered more defences built around the besieging army, should the combined enemy forces decide to attack the Imperial Army directly.

Three months later, the city and monastery of Rascia yielded to the Imperial Army. Among the prisoners taken were the wife and mother of Prince Vukan. The successful siege was a relief for Marshal Isaakios, who had grown troubled in the intervening time. Each day the army received rumour that the heretical uprising was gaining in strength. The connection between Pavlos and Prince Vukan was undeniable, with the banners of Bogomilists and Diokleians frequently spotted alongside.

Not a week later, Isaakios Kontostephanos received orders from Constantinople to garrison Castle Rascia with a regiment of infantry, and to scatter the rest of the army to their respective strategoi. Delighted with his victory with few losses, Isaakios rode with his cataphracts back to Epirus.

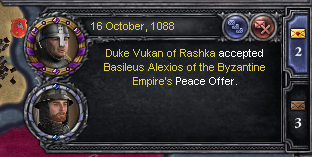

The peace that Alexios negotiated with Diokleia was a testament to his great patience and foresight as a ruler. In exchange for peace and the return of his family, Prince Vukan agreed to cede the county of Rascia to its rightful owner, give up the royal arms he claimed, and disperse the heretic peasants back to their fields. Alexios graciously pardoned Pavlos, under the condition that all Bogomilists either abandon their heresy or relocate to Diokleia. Over the next decade, tens of thousands of Macedonians and Bulgarians would take the chance to emigrate to the lands of Duke Vukan, who communed with both Rome and Constantinople, and accepted all heresies.

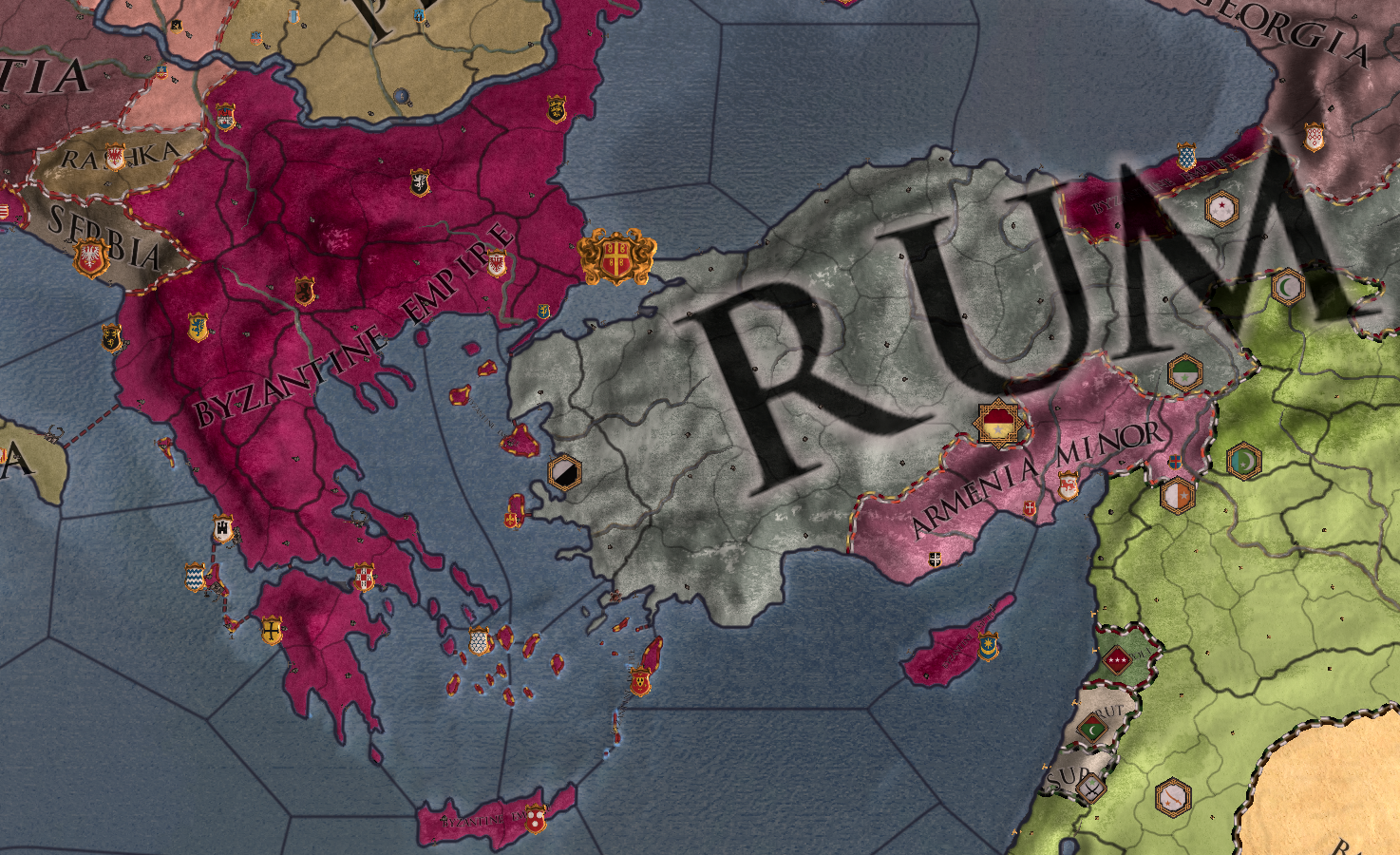

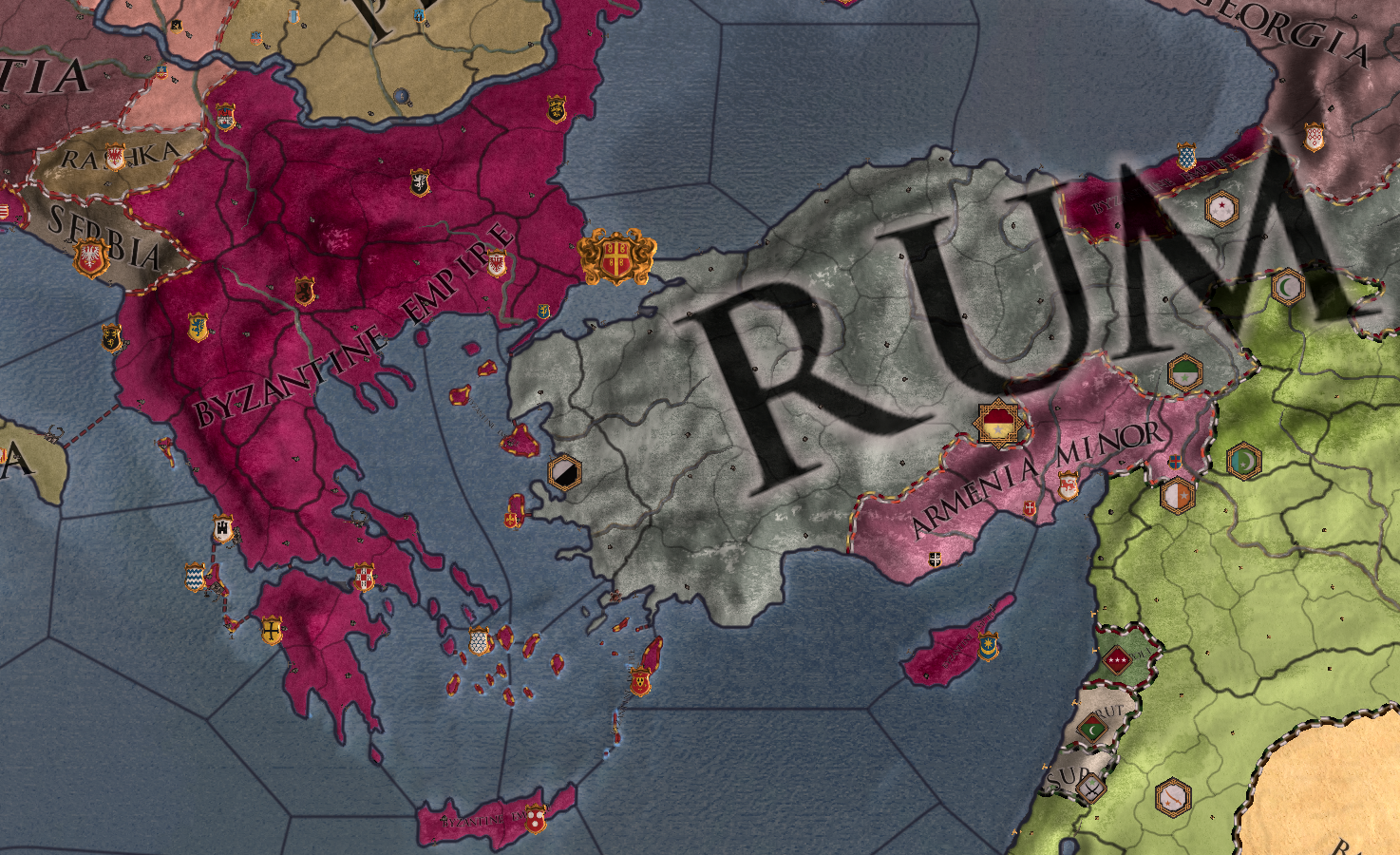

The Empire enjoyed a peaceful winter, but Alexios’ mind was tireless, and his ambition to recover land from the Seljuk Turks was unabated. The Battle of Manzikert could be counted amongst the greatest blows ever suffered by the Roman Army, alongside Cannae, Teutoburg Forest, and Yarmuk. To add insult to injury, the Turks had started to call themselves the Sultanate of ‘Rome’. For over a century, Byzantine Emperors since Romanos II Porphyrogenitus had endured the insult rendered by the King of Germany and the Bishop of Rome. At least those ‘Romans’ had claim to the city of Rome itself. But for this Muslim sultan to claim lineage from Aeneas, Romulus, and Julius Caesar was a far greater offence. One that Alexios could stomach for no longer.

A secret message sealed by Alexios’ signet ring was delivered to the See of Rome in February. No response came from Bishop Clement, whom many knew was under the thumb of the King of France. Furious, the Emperor sought the support of Bishop Odo, who was recently elected ‘Pope’ by those cardinals who did not bow to King Henry. Odo had been denied entrance to St Peter's itself by the Antipope, but Alexios knew much of the West still saw him as the true Bishop of Rome. After weeks of deliberation within the Curia and months of correspondence with the great kings of Christendom, Bishop Odo of Rome, also called Urban II, announced the creation of a new order of Knights whose express goal was to reclaim the Holy Land from the heathen who had seized it from Byzantium.

In addition, Urban II sent back a promise for military support against the Turks within the next few years. He was asking kings and princes from Galicia to Scotland for armies, and the muster would be a slow process. They would also need time to deliberate over the target of the Crusade, claimed the bishop. In exchange, Urban II asked for the Emperor to recognise his legitimacy over the pretender Clement III, who occupied the See of Rome. Implied within the request was the always-thorny issue: Urban II asked for Papal primacy to be acknowledged by the Emperor and Patriarch.

In truth, neither Alexios nor Patriarch Nicholas cared much for the politics in the West. However, they maintained a firm stance that whoever the Bishop of Rome was, he was only

first amongst equals, and not the Pope and successor to St. Peter. Though the response was written with the utmost diplomacy, some among the Byzantine court would wonder if the refusal would contribute to Urban II’s much-delayed declaration of the First Crusade, or to his failure to deliver on the promise of help against the Sultanate of Rum.

During the summer of 1089, Isaakios Kontostephanos commissioned an icon of John the Baptist for the chapel in Epirus. We have learned about this from a letter addressed to his brother Stephanos, dated to July 1089:

Brother,

The vineyards and young girls of Epirus are better for me than the court and courtesans of Constantinople. Last year’s war has greatly fatigued me. I fear that I will not have the strength to direct a long campaign against the Seljuks. Alexios wants me to in the next few years.

A young artist has asked for my patronage for a likeness of John the Baptist. It is expensive, but it is a small price to pay for my immortal soul. It will be complete in August. I have talked to the artist about the life of Saint John. John knew all his life that the messiah would arrive. He lived a simple life, and did not teach as Jesus Christ did. Some men may feel Christ to be too difficult to emulate, but all men can hope to live as John did: in the service of greater men than he.

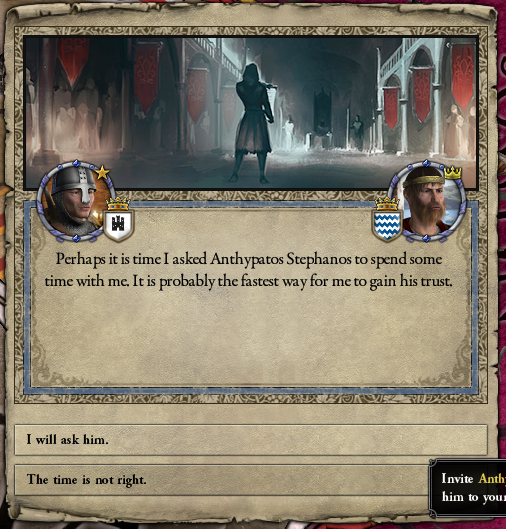

I feel the age in my bones. You may as well, in two years when you are fifty. It is time for me to look back and reflect on my life. I have lived a long, sinful life, and I have known many more women than you. How is it that you have a son when I do not? Unless I am surprised within the year, I may never have an heir of my loins. You may be tall, Stephanos, but you must carry the Kontostephanos name for me. I have asked Alexios to consider you as my successor, and regent if I beget a son.

Brother, we have not talked much since your wife died. Come to Epirus, if the Ionian Islands are not too beautiful to leave. I will show you around Arta and the castle, for I expect it to be yours soon. You can bring your boy, so that I can see the future of our house. We can visit the bridge over the river Arachtos, and there we can wash his feet.

Isaakios Kontostephanos

Unfortunately, that summer also saw the second marriage of Doux Stephanos. Too busy to leave his island home, the doux sent an apologetic letter to his older brother. He would visit Epirus the next summer with his son and new wife, Stephanos wrote back. He sent grain and olive oil to Isaakios, with a promise to strengthen their bonds of brotherhood. However, the return letter went unread, the bottles of oil unopened.

The icon of St John was displayed for the first time at the last rites of Doux Isaakios Kontostephanos, who is now with God.

From the personal writings of Stephanos Kontostephanos the Older:

My brother. We have grown apart in our old age, but you found for me an opportunity to come to court, and the rest is history. I hope to administer Epirus well in your memory, and make something more out of our house in my lifetime. You shall be remembered as the man who began it all but never saw the glory.