(Prologue) I: The Hand of History

(Prologue) I: The Hand of History

1930 found Britain’s Labour government in dire straits. Having just missed out on a majority in the previous year’s General Election, Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald had been forced to rely on the goodwill of the increasingly fractious Liberal Party to maintain his ministry. Added to this, the coming of the Great Depression had led to massive unemployment and a general economic crisis. As MacDonald and his conservative Chancellor of the Exchequer, Philip Snowden, attempted to combat the crash they not only faced criticism and pressure from the Tory Opposition but dissent from within the Labour Party itself. Alongside the established rebels within the Trade Union Congress and left-wing ILP [1], the leadership faced a new faction of young economic radicals led by the charismatic Oswald Mosley.

Since his stunning victory over Conservative grandee Neville Chamberlain in the 1924 General Election, Mosley had quickly made a name for himself, based as much on his dominating presence in Parliamentary debate as his advocacy of unorthodox Keynesian economics. Soon a following had grown around him and despite his intense (and often vocal) dislike of the ‘old men’ of the Party, earned a place in the 1929 Cabinet as Lord Privy Seal, effectively giving him a stake in the issue of unemployment. Despite hopes from acolytes that his inclusion in the Cabinet would see a shift towards their way of thinking, MacDonald and Snowden vetoed proposal after proposal to combat joblessness on the grounds of cost. Then in May 1930, flustered by his colleagues’ inaction, Mosley wrote a final memorandum, outlining a broad programme of work projects to combat the millions of unemployed. Again the Chancellor scoffed at such “wild cat finance” as he called it, with MacDonald in agreement. Infuriated, Mosley stepped down from Cabinet. In a fiery resignation speech he attacked what he saw as the Government’s outmoded concerns and general stagnation. Much to the Prime Minister’s embarrassment, the speech received thunderous applause from both sides of the House [2].

Following on from this victory, Mosley began to mount external pressure on the Government. At the Labour Party Conference in October he made a policy proposal based on his memorandum. Despite being defeated the proposal garnered over 45% approval, a clear indicator of his growing popularity and influence, as well as growing grassroots discontent for Snowden’s economic policies [3]. This situation finally came to a head in July 1931 with the publishing of the May Report. Established to look into the Depression’s effects on National Expenditure, the Report predicted a 1932 deficit of £120 million, and called for severe budget cuts to narrow the gap. MacDonald accepted the findings and put a controversial retrenchment plan to his Ministers. After hours of debate they proved deadlocked by an even split for and against the cuts, and eventually the Cabinet agreed to resign.

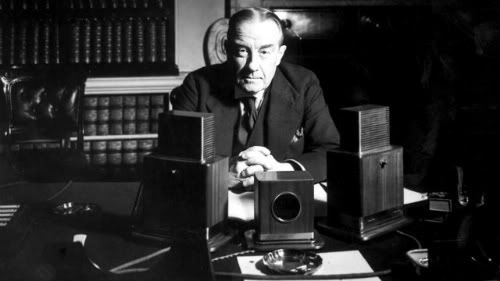

Mosley Resigns, David Low, May 1930

MacDonald, greatly disheartened, informed the King of the situation. George V suggested the possibility of a National Government, although he doubted how receptive the other parties would be. The next day the Prime Minister met with Stanley Baldwin and Herbert Samuel, leaders of the Conservative and Liberal Parties respectively, to discuss the issue of a possible coalition. The meeting however proved a failure as both MacDonald and Baldwin were unconvinced of the other’s commitment to such a scheme, despite the pleas of Samuel [4]. As such, the Prime Minister despondently returned to the Palace one last time on July 25th, his ministry to be replaced by a Conservative-Liberal emergency government.

In the aftermath of the government’s collapse, Ramsay MacDonald made it clear he would not be staying on as Leader of the Labour Party. After officially announcing his intentions on August 25th, two candidates put themselves forward for the Leadership, the ever vocal Oswald Mosley and Arthur Henderson, a Labour veteran firmly planted amongst the ‘old men’. Despite indications it was to be a close run thing, a clash between the Young Turks and the Party establishment, Henderson had little interest in taking the helm, predicting a disaster at the next general election [5]. Unwilling to take the poisoned chalice and much to the anger of the likes of Snowden, on August 30th he stood down from the election in the name of Party unity. The next day, a year after his policy defeat, Mosley was elected unopposed as Leader of the Labour Party.

The make-up of Parliament now brought a new issue to the fore of discussion, that of the gold standard. Baldwin’s coalition government, with the exception of several dissenting Lloyd-Georgite Liberals, unanimously supported the retention of Pound Sterling’s link to gold supply. In the Opposition benches however, things were more mixed. Although Mosley and his close allies lambasted the outmoded financial system as they saw it, many of the old guard and even some within the ILP looked on nervously. The TUC were the most vocal opponents of Mosley’s ideas, with Trade Unionists openly demonstrating at his public appearances [6]. However by the end of September, Mosley was to be vindicated. The Bank of England, faced with the deflation caused by fixed gold sales, only worsened by the economic climate, called for the end of the gold standard. Much to Baldwin’s chagrin he had little alternative. Within a few days, amidst warnings of hyperinflation and economic meltdown from orthodox thinkers, it quickly became clear such apocalyptic fears were unfounded.

Baldwin calls a General Election, September 1931

Despite this embarrassment the Conservatives decided to call a General Election for October. Not one for coalition politics and with the issue of the gold standard now gone, Baldwin was confident he could secure a majority. Similarly both the Liberals and Labour were confident of strong gains, with Samuel convinced of increasing his party’s influence over the next administration, while the Mosleyites hoped their new direction and recent victory would attract voters. The Labour manifesto, little more than an expanded version of the 1930 memorandum emphasised this change. Alongside work projects, Mosley called for Empire Free Trade protectionism or ‘insulation’ as he dubbed it, to strengthen British industry. Despite gaining support amongst many disillusioned working-class Tories, plenty of voters were still unconvinced by the last Labour government’s showing.

Conservative: 291 (+31)

Labour: 257 (-30)

Liberal: 58 (-1)

Other: 9

Total: 615

The General Election results ironically proved a disappointment for all parties. Although only moderate losses for Labour, Mosley considered the results a personal humiliation, while Baldwin failed to gain a majority, forced to rely once more on the Liberals who themselves had been disappointed by their complete lack of new gains. Although the overall make-up of Parliament had changed little, by the New Year the Prime Minister was coming under increasing pressure from the protectionist wing of his own party for new tariffs, something which the predominately free-trade Liberals simply wouldn’t stand for. As such Baldwin was forced into a tight balancing act to maintain his alliance, throwing his own party an ineffectual review of free-trade policy in February to buy time. Then in April several Conservative backbenchers organised a Private Member’s Bill, calling for a ten percent import tariff on non-Imperial goods. Despite being quickly quashed by the whips, the effects of the Bill were plain to see, as dozens of Tory MPs cheered and spoke in favour of the motion, much to the anger of Samuel and his fellows. This was soon followed by a speech from Hugh Dalton, the Shadow Chancellor, implying Labour support for any future Tory Bill on protection, much to the horror of Baldwin and the Liberals.

Labour’s machinations and the growing divisions within the Government soon caught the attention of Lord Beaverbrook, the famed press magnate and ardent supporter of Imperial Preference. Although a loyal Conservative, Beaverbrook disliked Baldwin and knew the present coalition government would be unable to provide the strong protectionist policies he desired. At the same time he met with Mosley to discuss the issue and found many of his anti-Left fears allayed, saying the man had “the interests of the Empire at heart”. Labour’s Leader had a similar meeting with Lord Rothermore and again, despite his Tory leanings, they found common ground on protection. Increasingly less enamoured with the Government with every passing day, the two media barons resurrected their ‘Empire Free Trade Crusade’ campaign within the Daily Express and Daily Mail respectively, which would prove to have a critical impact of the events of the summer.

Mosley Speaks! Manchester Free Trade Hall, June 1932

In late May, the aged Donald Maclean, Liberal MP for North Cornwall passed away, precipitating a by-election. Although a marginal seat, Baldwin naturally refused to oppose his allies. Then in June, a young protectionist, Alan Lennox-Boyd, stood as an ‘Independent Conservative’ candidate, backed by the Empire Crusade. Labour too backed him, calling on their supporters to vote for protection. The Prime Minister was aghast at the situation as Beaverbrook and Rothermore bankrolled Lennox-Boyd’s campaign. The final straw came as Leo Amery and other protectionist Tories arrived in the constituency to speak on behalf of the rebel candidate. On June 15th, as word came in of Liberal defeat in North Cornwall, Samuel and his party resigned from the ministry, and after little over seven months, Baldwin was forced to call another General Election.

The campaign proved vicious as both Labour and the Tories were determined to gain an outright majority, harried the Liberals as much as each other. Baldwin, now unimpeded by Samuel was free to speak for protection but his recent record hardly endeared him to many voters, let alone many Conservative Party members. Meanwhile Mosley fought fiercely, focusing on working-class Tories with a platform of patriotism, social reform and protection which had seen him come to dominate his Birmingham heartlands in the late 1920s. When the results of the 1932 General Election were finally announced on June 30th, Britain awoke to her first majority Labour government.

Labour: 319 (+62)

Conservative: 251 (-40)

Liberal: 36 (-22)

Independent: 1 (+1)

Other: 8

Total: 615

-----------------------------------

[1] Independent Labour Party: despite their name, an official faction within Labour, though they’re core members certainly have a reputation as mavericks.

[2] Same as OTL: it should be remembered that prior to his turn to Fascism to fulfil his goals, Mosley was certainly the leading Young Turk in the Commons and widely respected.

[3] Due to the POD, Mosley has a more established base within the Labour Party by 1930. As such he is less inclined to leave for the fringes, both because he has a better chance of achieving his goals within a mainstream party and he has more sensible advice.

[4] Baldwin and MacDonald were never too keen on joining up IOTL; here butterflies see them both in a more honest mood.

[5] Henderson took the leadership in OTL out of duty, as there was little alternative, here however things are different.

[6] The ‘Red Baronet’s background is a world away from the humble origins of Kier Hardie or even MacDonald. Needless to say, Mosley’s outsider image and technocratic predilections do not enamour him to a lot of TUC men.