Cāk Mitradatte, although the son of a Western barbarian and a believer in a foreign creed, nonetheless lived according to the principle of self-restraint and love for the people. Respectful and courteous, as well as loyal and benevolent, Mitradatte attended to the root and raised his sons in strict accordance with the rules of propriety. Through his cautious comportment he brought prosperity to his state, attracted the tribe of Qiuci [Kucha] to him by his benevolence, and thus expanded his borders. Thus I have transmitted the biography of Cāk Mitradatte.

Biography of Cāk Mitradatte I

Cāk Mitradatte, the first

jiedushi of Shule [Kashgar], was a native of the Canglang Mountains, and belonged to the same Sai [Saka] tribe who ruled Yutian [Khotan]. He was appointed by the Tang Emperor Yizong as the governor in the seventh year of

xiantong (867 AD). He was given a scroll of appointment by the Son of Heaven, which read thus:

Hail, Mingtedai, descendant of the Shi clan. Receive from Our hands this seal of authority and this six-sided banner. We hereby entitle you the jiedushi

[military governor] of the far western region of Shule, where for generations to come you and your descendants may protect the westernmost pass of the Tang Empire from the evil barbarians. We urge you to remember that loyalty which you owe to Heaven, and dutifully constrain yourself to the middle road. Conduct yourself moderately and control your appetites, for the well-being of the state which you rule. Hear this, jiedushi

, and take warning!

Mitradatte studied the

Spring and Autumn Annals in his youth, as well as the

Gongyang Commentary, the

Odes and the

Rites, from which he began to inquire into the nature of things. He followed the barbaric foreign rites of the Jing religion [Nestorian Christianity], and held the

Chunfen festival of Bosi [i.e.

Nowruz] in special reverence. However, being circumspect in speech, upright in judgement and meticulous in conduct, he was recognised by the men of Shule as a man of learning and respected for his righteousness and breadth of knowledge.

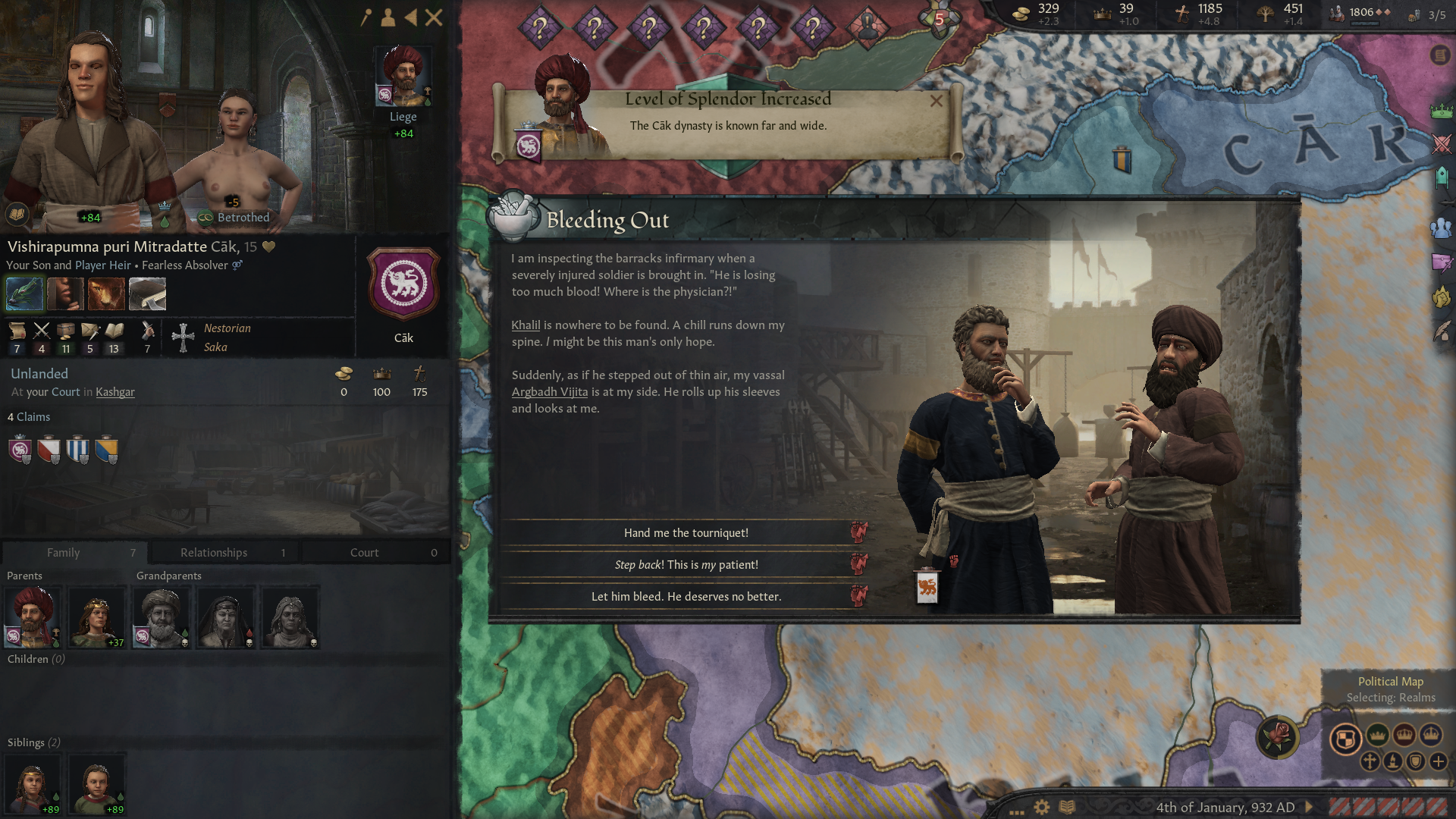

Mitradatte’s caution and virtue were evident even in his inner chambers. In his whole career he only ever consorted with one woman: his wife Lady Tang [see

Biographies section ‘Families Allied to the Princes of Shule’]. Lady Tang was an Assyrian healer from Dashi [Arabic Caliphate], over twenty years his elder, whom he chose among several candidates for her thoughtful discretion and mild character. She bore him two sons, Haskadatta and Khuradatta, as well as a daughter. During her time serving as his personal physician as well as his wife, Lady Tang notably managed to cure a lingering ailment the

jiedushi suffered – only after a gruelling regimen of diet, exercise and meditation. After Lady Tang’s death, he grieved bitterly for seven years, and never took another woman into his hall.

He made several journeys to the Tang capital at Chang’an during his lifetime. Chancellor Liu Zhan offers this description of him, based upon a visit he made to Chang’an in the first year of

ganfu [late 874 AD] to offer tribute in person to the new Son of Heaven [Emperor Xizong].

The jiedushi

of Shule is middling tall in his person, being over six chi

in height. His features, though they could be called handsome, are those of a fierce Western barbarian: he has a high bulbous nose, full lips which are too quick to frown, and thick, hairy brows, and his arms too are covered with brown hair like a monkey. He wears the garb of the barbarian, including a scarf wound around his head in place of a cap. Based upon my own observations, it seems that he suffers from a chronic stagnation of his hepatic qi

[1]. Even so, his expressions are humble and serene, and his bearing is civil. In action he is deliberate, in discourse reasonable, in temper peace-loving.

In matters of governance, Mitradatte attended to the root and allowed the branches to grow of themselves. When shown the surplus of the state, his ministers disagreed on what should be done with it. One suggested building defensive emplacements and gathering weapons. Another suggested decorating the temples and offering elaborate sacrifices. But Mitradatte himself answered:

‘Mencius once said: “The trees of Mount Niu were once beautiful. But being situated in the borders of a large state, they were cut down with axes and pruning-hooks. Could they retain their beauty?” And he also said: “Don’t interfere with the farmers’ seasons, and the grain will be more than enough to eat. Don’t put fine nets into pools and ponds, and there will be more than enough fishes and turtles to eat. Only go into the hills and woods in season with axe and pruning-hook, and the wood will be more than can be used.” Even the Master himself said: “To rule a state of a thousand chariots: attend to business, be honest, be thrifty with money, and love the people. Let people work only at the proper time.” Gentlemen, we must look first to the orchards and vineyards. Let apricots be planted upon the ten-

mu estates, and mulberry trees around the households upon the five-

mu estates, and berry bushes upon the edges of the courtyards. Let the harvest occur at the proper time, and let no complaint be made about gleanings from the roadsides. In this way the state will prosper. A prosperous state may offer the reasonable and bloodless sacrifices in the temples. Then we may attend to walls and weapons.’

Mitradatte himself broke the ground and planted trees in his own courtyard. And then the Sai people in the state of Shule planted these according to their season. Apricots, mulberries and other berries flourished. Shule began producing wine and fine silks for trade. The Tuhuoluo people of Qiuci [Aksu] began to take notice, and they grumbled to themselves:

‘The men of Sai have so much fresh fruit they can feed it to their goats and cows; while here even dogs starve and children die of hunger. Their young men work in the fields and look after their parents, while the Huihu Yiduhu conscripts our young men to serve them and fight for them in wars. It must be that the

jiedushi of Shule is an accomplished man. Let us appeal to him! Let us appeal to him!’

The embassy to Cāk was led by a young Tuhuoluo named Liang Baodeng, father of Liang Zhisheng [

Jñanaghose Lyam]. Liang Baodeng appealed to Mitradatte’s benevolence and upright nature, pleading his people’s long-suffering and the unjust treatments they had borne. Upon hearing this appeal from the Tuhuoluo, Cāk Mitradatte was moved to pity. He said to his ministers:

‘The state of Xizhou is vast, and it is outwardly strong. The Huihu are fierce barbarians, and they follow the evil teachings of Moni. However, Xizhou is a paper tiger. Its conscripted men are exhausted, while the ministers build lavish pleasure-gardens, the lords stage elaborate dances, and the king inclines his ear to charlatans. The Tuhuoluo have requested our help. If they flock to us, we can defend them! Will God [

Aluohe] deny us in such a cause?’

And so Mitradatte called up his riders, his chariots and his archers, and himself led the punitive expedition upon Xizhou. In this he was aided by Bu Ye Gong of Liangzhou, a younger son of the Yuan family of Chenjun. God, which is how the Nestorians call Heaven, indeed favoured Mitradatte, who managed to capture the son of the Yiduhu in battle, and bargained with him to release a thousand households of the Tuhuoluo of Qiuci to his overlordship.

Mitradatte and Bu Ye forged a fast bond. Both literary men, they delighted in the pursuit of knowledge, and found a shared love in the study of the ancient classics. Ye promised his daughter Nizi to Mitradatte’s son Haskadatta. They spent time in the orchards, bonded over wine and composed poetry together. Mitradatte’s poetry highly extolled the virtues of his friend, and this poetry became known throughout the Guiyi Circuit.

Bu Ye, who was modest and retiring in character, proved his friendship to Mitradatte time and time again. He once sent a live hart which his hunters had captured to Shule. When it arrived, Mitradatte clapped his hands in gratitude, and remarked: ‘King Xuan of Qi could not bear to see the ox butchered to consecrate the ceremonial bells, and told his servant to let it live – not out of greed, but out of pity. Now I understand this saying! Let the beast roam the courtyard freely.’

And when Bu Ye died, Mitradatte went out into the streets, knelt down in the dust of the road, heaped it upon his head and wailed aloud to the heavens, crying: ‘My sweet Lady Tang is taken from me! My poor daughter is taken from me! And now Bu Ye Gong is taken from me! Why do you begrudge them to me, God? Why do you begrudge them to me?’

Twice Mitradatte undertook journeys into the far western regions. His first journey was to Baghdad in Dashi, which was his wife’s hometown. His second journey was to Shiraz in Persia. Here he obtained copies in the original language of the text of the

Bosi Gujing which he then translated into Chinese himself. The commentaries he added tried to show that the doctrines of Jing, and the coming of Lord Jesus Christ, had been foreseen by the ancient sages of Persia; and also to show the doctrines of Moni as evil and false.

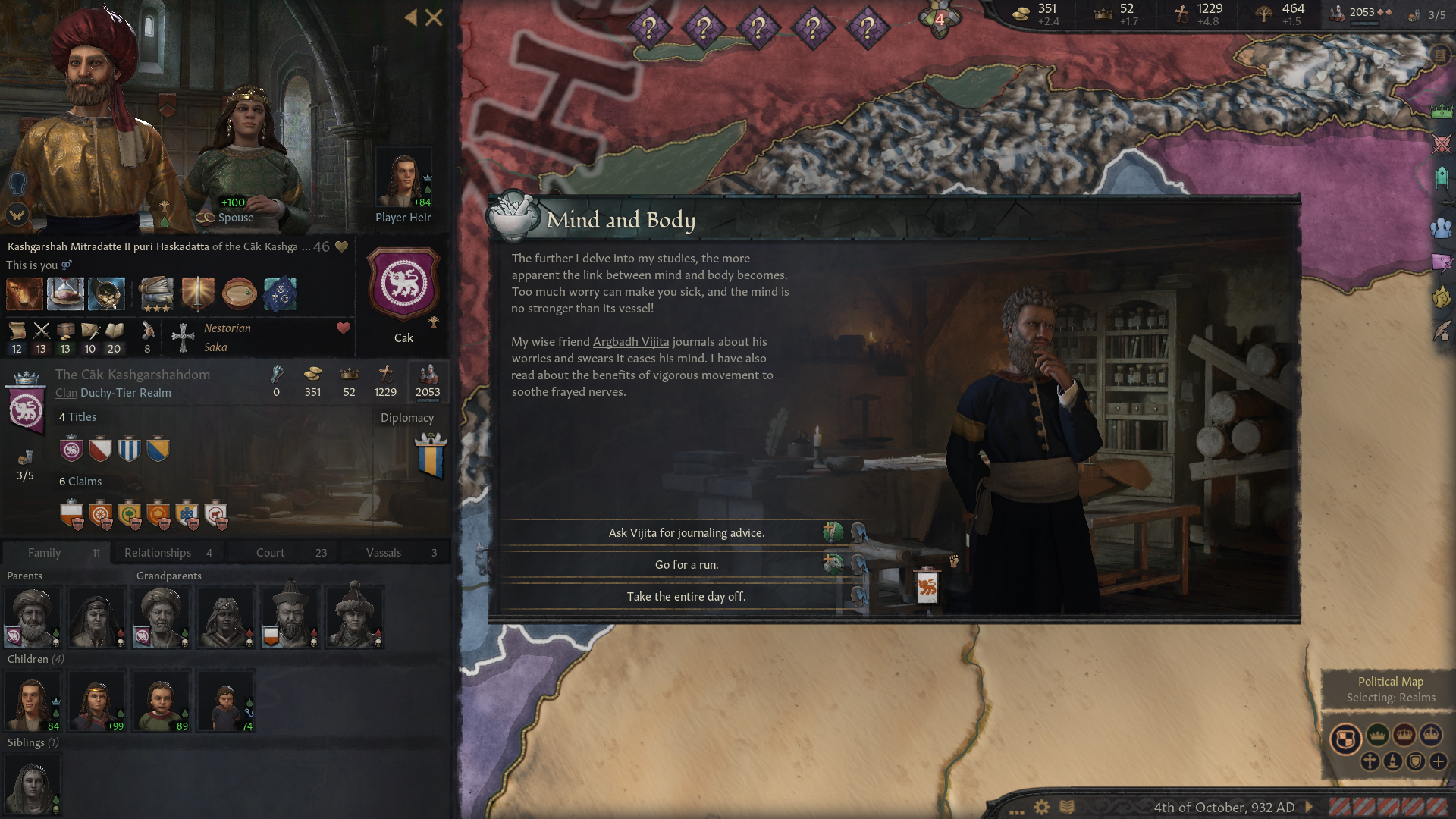

In his twilight years, Cāk Mitradatte associated with various shamans, hermits and geomancers. He also kept and maintained a small garden, which he used both to retire for quietude and to inquire into the nature of plants. At least two of his ministers, including the hermit Ailu Musa, remonstrated with him, believing him to be wrongly pursuing methods for extending his own life at the expense of the state. Mitradatte meekly inclined his ear to them, and mended his ways. At the end of his life, he was given a simple burial outside Shule. After the State of Qi was founded by Viśirāpumnā, as the progenitor of the Cāk family, the

jiedushi Mitradatte was given by his great-grandson the posthumous name of King Gao ‘the Lofty’ of Qi.

The Master said: ‘Since I can’t get men who act according to the middle way, I must find the adamant and the cautious. The adamant go after things, the cautious restrain themselves from doing certain things.’ Mitradatte cannot be said to have followed the middle way. However, although he did not attain to the golden ideal, he was cautious, and understood how to restrain himself. First restraining himself, he then raised his son and his grandson to follow his example. Haskadatta proved trustworthy and scrupulous in all matters, practising restraint and eschewing even the smallest lies; and the second Mitradatte encouraged thrift by avoiding rich foods. In this way, Mitradatte avoided disaster and established order in Shule, handing the rule on to subsequent generations with an easy heart. Is this not a great accomplishment?

[Original source text]

石明特帶,然西戎子且胡教徒也,并活隨道矣。敬而禮者,且忠而慈也。石明特帶顧根養子嚴迪道。正行爲國富、仁引龜兹氏、此行拓其邊。此寄石明特帶傳。

《磧高王傳》

石明特帶,疏勒始節度使,蔥嶺人,治于闐國之塞部落之一。大唐懿宗皇帝咸通七年上疏勒王座也。天子送其遴卷,道:

「嗚呼,石氏之裔明特帶!受兹命璽與六縿旗。朕名爾遠西邊疆疏勒節度使,為爾子孫要把激西闗給我大唐防惡胡。朕勸汝記:該天之忠、仔按中庸。道和行、制汝欲,以汝治國之益。節度使,其戒之!」

明特帶少年時學《春秋》與其《公羊傳》、《詩經》、《禮記》:以其始問物性。跟隨景教之胡禮,特敬波斯春分節之慶。但其言慎、其裁正、其作細。疏勒人認其爲雅人、佩其義行與博知。

石明特帶之細在内官顯。整輩只配一妻唐姬。唐姬,來自大食亞述醫,比節度使廿年老者。從幾娘之中,節度使選唐姬:是為其周謹、溫性。為節度使生兩男:獲特帶與護特帶。且生一女。當宮醫且妻時段,成功治節度使挨之頑疾,只待難苦食飲、鍛煉、冥想方案而決。唐姬去世后,節度使七年悲痛,再不接妻入宮。

疏勒節度使幾次訪長安。慿其乾符元年親自拜天子呈貢,劉占宰相如此描之:

「疏勒節度使身微高,六尺兩寸。五官爾秀,則西戎之:鼻高而鼓、唇厚好愁、眉粗茸茸、四肢像猴滿毛。其裝戎式,頭絕帽換巾乎。以臣觀之,其肝氣鬱結而患。則其容卑寧、其行為文、其做細心、其曰合理、其性意安。」

以政,明特帶顧根,讓指然長。見國之剩,臣執何用。一位道:建壁採戈。另位道:修寺巧祭。且使曰:

「孟子曰:『牛山之木嘗美矣,以其郊於大國也,斧斤伐之,可以為美乎?』再曰:『不違農時,穀不可勝食也;數罟不入洿池,魚鼈不可勝食也;斧斤以時入山林,材木不可勝用也。』連子曰:『道千乘之國:敬事而信,節用而愛人,使民以時。』咱首顧圃園。百畝之田種杏;五畝之宅種桑;場田之邊種虅。使穫以時,禁怨拾秕,如此余國。國有余後,寺理拜祭,建壁採戈。」

明特帶親自園上耕土種樹。然疏勒塞人安季種之。杏桑莓薈也。疏勒國始釀酒、繅絲為商。龜兹吐火儸人理之,自叨:

「塞人鮮果余、飼牛羊之乃!焉犬餓童飢。塞男耕田照老也。焉亦都護召男為努兵乃!疏勒節度使不得已君子也。申之乎!申之乎!」

吐火儸少年梁保登為申使,亦即梁智聲之父。梁保登呼籲明特帶之仁義、辯其人之困、解其人背之壓迫。以聞吐火儸之訴,名特帶哀之,到臣曰:

「西州廣汎,外顯强壯,回鶻兇夷,信摩尼邪教矣。但表實是虛也。兵盡為戰、臣建樂園、公開侈舞、王聞騙者。吐火儸問助,集之能保之!此事業,阿羅訶能否吾呼?」

然節度使徵馬、車、弓,親自討西州。此事有涼州卜曄公之助,亦即陳郡袁氏之小後代也。阿羅訶,是景教徒稱老天之名,是向之,戰而捕亦都護之子為質,議放之龜兹千宅。

明特帶與卜曄結親友。兩文者好知、又愛學古經也。卜曄讓其女霓子嫁明特帶之大子。倆待圃,飲酒,撰詩。明特帶之詩大誇其友之德,全歸義軍播之。

卜曄公性謙羞,而為友逢逢著誠。其獵者陷之生鹿賜給疏勒節度使。到之,明特帶謝與拍手而曰:

「齊宣王不忍見釁鐘之牛觳觫,讓僕舍之,不以貪而以憐。當愚解話!舍之漫游院!」

卜曄死。明特帶出街,跪塵注頭上,向天大啼:

「天搶吾愛人唐姬也!天搶吾敝女也!天乃搶吾卜曄公矣!阿羅訶,何吝之乎?何吝之乎?」

兩次明特帶游遠西域。甲游到大食白達市,其妻之籍。乙游到安息失剌思市。此市受原言之《波斯古鏡》,自己翻譯成唐文。寫之評論證示波斯古聖預知景教彌施訶出代,揭摩尼教之邪虛。

暮年時,節度使聞異巫、遁世者、卦師等。亦種顧小藥草園,以找寧、詢禾性。其臣兩者,含埃盧穆薩遁世師,誡之,意是求延命忽國之異道。節度使順而聽之,歸正道。死,疏勒邑外葬單禮而已。建磧國之後,無脈雄沙王為其曾祖父明特帶節度使石氏元祖之諡號:磧高王。

子曰:「不得中行而與之,必也狂狷乎!狂者進取,狷者有所不為也。」明特帶不如得中行也。而且不達中庸,但狷之,解有所不爲。有所不爲,後養男與孫習其榜。獲特帶示誠,萬事慎完,欲望剋制,逃避細謊。名特帶二世節度使勤儉節約,戒除富食。此道明特帶免災,疏勒國之政理,安心傳統給後代。何其盛乎?

[1] This could be a reference to a mental illness, such as depression or anxiety.