Hello Everyone and Welcome to another Tinto Talks, the Happy Wednesday when we talk about the most secret game with the code name “Project Caesar”

This week we’ll talk about the ages and institutions, concepts that were first introduced in a patch to EU4. They were a convenient mechanic to make different eras feel different, but soon became too gamified with development ruining the institution game.

Every age introduces several new “REDACTED”, adds several possible new government reforms you can pick from, impacts the price stability of goods, and also has some direct impacts on every country. In every age, the amount of gold you pay for your raised levies will increase, and the size of the army you are expected to have increases. Each age is global in the world, but its true impact is gradual. There is no special mana you gain through achieving goals that you can use to stack modifiers with.

Ages of Traditions have passed, and we have just entered the Age of Renaissance here..

Each age also has three institutions that will spawn, each will unlock “REDACTED” and spread across the world.

We have designed the institution spawns to be more rigid for the first ages, and be more flexible in later ages, to guide the game in a certain direction. For those of you who dislike the dynamic spawning of institutions, you can put it in “historical” mode, and it will spawn in the same location every time.

There are only two options for this rule at the moment.

The spread takes time, as it can only spread through adjacent locations or across a single sealane, unless you have trade routes from a market center that has embraced it. The speed it spreads is also impacted by the literacy of the population. If you have embraced an institution, then it will spread in proportion to your control in your owned locations.

When an institution has spread to more than 10% of the population in your country, you can embrace it, meaning you will get access to the “REDACTED” it will give you.

As the technology system in Project Caesar is different than the one in EU4, missing an institution for a while is NOT a complete disaster, but more on that next week.

In later ages you can also start assigning a member of your cabinet to promote institutions in a province, which will then progress any institution you are aware of in the locations of that province. Promoting is heavily based on the burghers and the literacy of a location.

There are 6 ages in the game, and in 1337 we start in the Age of Traditions, and each age from there on lasts about a century.

It was the definitely the best of times...

Age of Traditions

Different societies have been established throughout the world for hundreds and thousands of years, and their foundations can be framed in traditions such as Legalism, Meritocracy, or Feudalism.

Legalism

We gave this institution the spawn point of Rome, even though there are plenty of places that could compete for it. Most of the Old World has this institution spread and embraced at the start of the game.

The theories behind Legalism have been integrating into Chinese societal structures for hundreds of years. The concept that pure idealism and domestic stability leads to a rich, prosperous state and a powerful army is deeply rooted in the forums of thought in the Eastern Asian domains. However, as merchants and migrants brought forth the exchange of ideas, the concept of Legalism made its way across the vast expanses of the Muslim world. There, it adopted the stance of a symbiotic relationship between heathens and believers in Islamic states. Legalism in Europe signified the rite of passage, from the dying grasps of the great Roman Empire to its remnant legal roots, many of which would later serve as the basis for new jurisprudence across the old continent.

Meritocracy

This has the birthplace in Beijing and at the start of the game, it has only spread through East Asia.

Many individuals of great prestige and in positions of power often chose to appoint those closest to them in influential spots. The advent of Meritocracy as an institution and a thought movement was largely popular in the courts of Imperial China. There, Confucius himself supported the notion that those who govern should do so on the basis of merit, not of inherited status. This led to the replacement of the Chinese nobility of blood ties to one based solely on meritocratic abilities. This institution's development would ripple across and beyond the borders of Asia and would eventually reach the royal courts of even European monarchs whose Nobles had a firm grasp on the mechanisms of power and authority.

Feudalism

This has its birthplace in Aachen, the capital of the Roman Empire under Charlemagne. It has spread in most of the Old World as well.

Over time, most societies develop a need for a common structure with stronger and more permanent institutions of government. After the fall of the Roman Empire, this need came to be filled by a number of institutions and customs that taken together are often considered to be part of the European Feudal system. For similar reasons, permanent government and societal systems have formed all over the world, some of which have roots that go far further back than Feudalism itself.

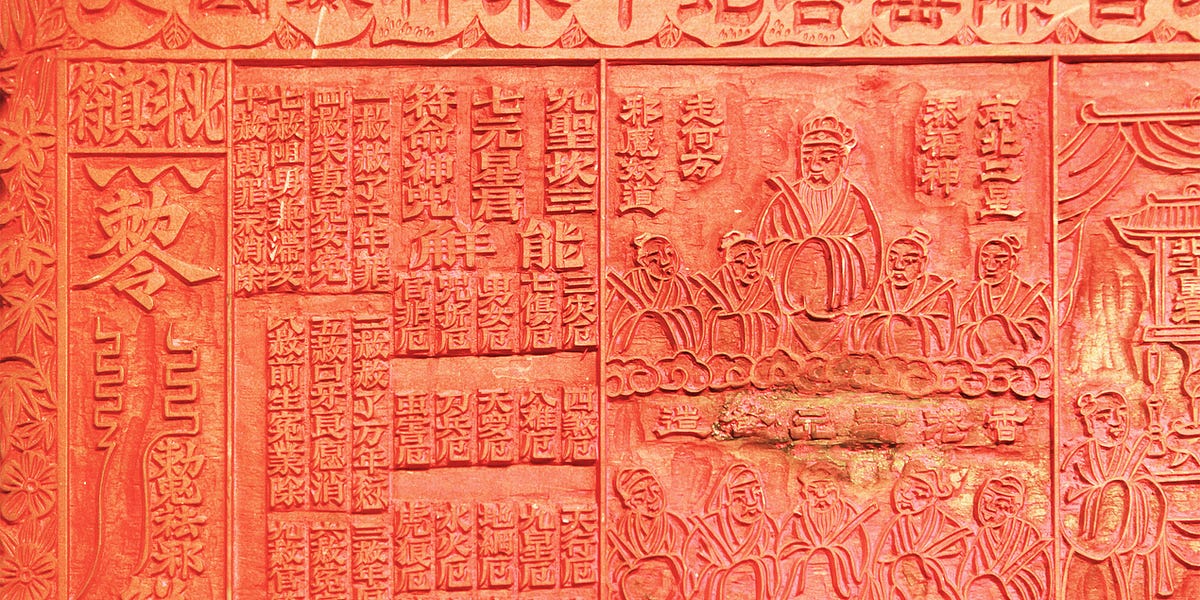

Have we show this image before?

Age of Renaissance

A new era of knowledge, arts, and progress is emerging due to growing interactions and institutions in the medieval societies affected by Pax Mongolica, the Islamic Golden Age, and the European Renaissance.

Renaissance

This institution will spawn soon after the age starts in a Northern Italian City with a University. The historical location is Florence.

Starting now in the 14th century, the wealthy and powerful in the Italian City states have been patronizing artists and scholars willing to explore the old Roman and Greek societies of their forefathers. As a cultural movement the Renaissance already encompasses most of the region and has had a profound impact on literature, art, philosophy, and music. Humanist scholars are also analyzing the society in which they live, comparing it to the ideals of the Classical philosophers. Renaissance Humanism has grown into a more mature movement, ready to permeate all aspects of society. A new ideal for rulers as well as those who are ruled is spreading as quickly as the early Printers can distribute copies of these new ideas. A true Renaissance Humanist is an expert on everything from politics and philosophy to art, textual analysis, music, and architecture. The Renaissance is now ready to reshape the world to better fit its classical ideals.

Banking

This can spawn in any town or city with more than 1000 burghers in Europe, North Africa or the Middle East, where the owner has a strong “Capital Economy” Societal Value. The historical location is Genoa.

Money lending has existed since metal-based coins appeared in Antiquity. However, it depended on some individuals and their family groupings or on the Ancient States. A shift occurred in the Middle Ages, encouraged by the renewed growth of long-range commercial activities on the Eurasian continent and its peripheries. Specialized moneylenders began to organize when Jewish communities started operating between the Christian and Islamic worlds. However, the boom of credit demand that followed the Crusades in the 12th century encouraged merchants in the Italian city-states to create larger structures for money lending, effectively founding the first Banking institutions, such as the Peruzzi and Bardi houses. More instruments were developed, like bills of exchange and debt bonds, and Banking dynasties such as the Medici, Fugger or Welser soon became as powerful as States.

Professional Armies

This can spawn in any location in Europe, which has some manpower produced, where the owner has a “Quality” Societal Value. The historical location is Paris.

Armies have existed since war was invented, many thousands of years ago. However, their form has changed over the centuries and different types of recruitment and organization have developed in different cultures and periods. In the Late Middle Ages, armies in a wide range of societies relied on levies based on the structures of feudal society, with knights and footmen forming a core that was levied seasonally. In some regions, however, states were powerful enough to finance standing armies, with professional soldiers who would be available for duty throughout the year. This system was also developed in Europe after the outbreak of the Hundred Year's War, being one of the main changes that promoted a Military Revolution in the Early Modern Age. Increasing the size and quality of Professional Armies, while finding new sources of revenue to finance them, soon became one of the main challenges for rulers around the world.

This looks like a nice place to add to the Spanish Empire!

Age of Discovery

At the dawn of the Early Modern era new continents are being mapped while feudal society is slowly giving way to centralized states. For an enterprising state this age can see the foundation of a worldwide empire.

New World

This will spawn in any port in Western Europe or North Africa, with more than 2,000 burghers, and where the owner has discovered the Azores and the West African Coastline. The historical location is Sevilla.

The discovery of the New World has heralded a new era not only for the colonizers and the colonized, but it has also led to the spread of materials and techniques as well as a realization of the vastness of the globe. As animals, crop types, silver and diseases spread across the Atlantic, the first steps have been taken towards a truly global economy. With foreign lands and people being mapped and documented, ideas as well as religious and philosophical debate are increasingly being colored by what we have found in overseas societies. Great minds feel the need to question what was once truth, and from Valladolid to Fatehpur Sikri, the nature of the world is now up for debate.

Printing Press

This can spawn in any location with more than 2,000 burghers, where the owner produces more than 5 paper and has an “Outward” Societal Value. The historical location is Mainz.

The ability to mass-produce the written word would revolutionize the spread of information and in many ways early modern society as a whole. Pioneered by Renaissance men such as Venetian Printer Aldus Manutius, the new art helped fuel the Renaissance by making the translated classics more widely available. Later the Reformation benefitted greatly from the ability to spread critical publications and translations of the Holy Scriptures. Now that Printing has matured as a technique and spread throughout Europe, hundreds of thousands of copies of everything from Religious and Political pamphlets to scientific treatises and instructions on how to behave are circulating the continent. With print shops growing evermore commonplace, rulers have found it hard to contain the new technique as the comparatively easy means of production means censorship can be sidestepped by moving business across a border or even just changing the name on a title page.

Pike & Shot

This spawns in a location, which has some manpower produced, where the owner has Professional Armies, more than 20 Army Tradition and a “Land” Societal Values, and have the gunpowder technology. The historical location is Innsbruck.

A new type of warfare began to develop at the end of the 15th Century, in the midst of the Italian Wars. The generalization of pikemen in the Late Middle Ages as an alternative to men-at-arms who could successfully face heavy cavalry charges was accompanied by the development of portable firearms, mainly matchlock arquebuses and muskets. The soldiers now adopt a new formation, in which the pikemen form a square, while the arquebusiers fan out to the sides and front, and seek cover behind or inside the square in case the formation enters close combat. This new type of formation, called Pike & Shot, was favored by German Landsknechts and Spanish Tercios, and was soon adopted by other armies, reigning supreme on European battlefields for nearly two centuries, until superseded in the early 18th Century by line infantry formations armed with new flintlock muskets mounting bayonets.

The heretic is trying to defend his heresy.

Age of Reformation

From East to West this is the age of religious conviction, debates and mass movements. In Europe, the protestant churches are entrenched while millenarianism takes hold of Iran and religious Syncretism shapes Indian society.

Confessionalism

This spawns in a town or city in Europe, which has a printing press, where the owner is Catholic, and the dominant religion is Catholic, and has a “Spiritualist” societal value. The historical location is Augsburg.

Catholicism has been regarded as a unitary entity for a long time, but the advent of the various Protestant Faiths has put an end to that. With the rise of a myriad of different interpretations of what the Faith should be, Christianity is all but united. But where before any deviance from the Church could be easily labeled as heretic, now the lines creating the differences have become blurrier at least. As such, there has been an increasing interest both for religious and secular authorities alike to clearly define the shapes of their specific confessions, enforcing their particular rules and views on all aspects of faith and life. This allows them a more firm grip on the faith of their population, but also increases the differentiation and thus animosity with all the other confessions.

Global Trade

This spawns in a market center in a city anywhere in the world that has among the most value of goods traded. The historical location is Lisbon.

Goods have been moved across continents since antiquity. But where this was previously limited to a set number of routes and goods such as the manufactured goods of India and China finding their way across the Indian Ocean and along the Silk Road, all trade is now increasingly becoming part of a greater world network. With the discovery of the Americas, sea routes around Africa and the crossing of the Pacific Ocean, local trade networks are being connected into one world-spanning interconnected web. Silver mined in the Andes is now being boxed and taken via Europe all the way to China and India. Iron mined and wrought in Scandinavia is being sold in West Africa by English merchants, and others are making a fortune just distributing cloth and spices within the Southeast Asian trade sphere. Local Indian merchants are investing in future European trade ventures. It may still be early to speak of a truly Global Economy, but surely the first seeds have been sown.

Artillery

This will spawn in any city in the world that has a gunsmith and a metal workshop, and where the owner has an “Offensive” Societal Value. The historical location is Constantinople.

The invention of gunpowder in Song China led to the development of a new device that would employ its firepower in warfare, the artillery. Although it spread throughout Eurasia in the 13th Century, its use as a common weapon system did not happen until the 15th century, as improvements in the cannon length and gunpowder recipe made artillery much more powerful, now posing a threat to stone-built castles and fortifications, the most common in Europe. Soon artillery would be used not only in sieges but also on battlefields, as smaller caliber guns now featured the mobility required to be quickly deployed and used. Its final development as a key warfare system would come in the 18th Century, especially after Napoleon perfected its use at key points during battles.

L'État, c'est moi.

Age of Absolutism

As governments wrest the absolute power in their countries from other parties, they are now able to devote themselves to the building of Empires. This is the age of the state, of rulers, and their armies.

Manufactories

This will spawn in any location with more than 100 building levels, and at least 20,000 Burghers, and where the owner has a “Capital Economy” Societal Value. The historical location is Derby.

While a number of technical innovations during the course of the 16th and 17th centuries have increased the output of production for some products such as iron or cloth to an extent, the biggest improvement in the field of production has come in the form of new forms of organization. By creating manufactories, often outside the city limits, merchant capitalists can both bypass the ancient guild laws that inhibit mass production, and pioneer ways to increase production through the organization and specialization of labor in one place. The forerunners of the later Industrialization were able to increase output by facilitating access to raw materials and mass organization of labor rather than by expensive new machinery. This is in itself a huge change over the often heavily regulated methods of old, however, and together with later technical advances this new mode of production will come to revolutionize society.

Scientific Revolution

This spawns in a location with a university, and a high average literacy, where the owner has a “Innovative” Societal Value. The historical location is Cambridge.

It is clear that the world is smaller now than ever before. The rise of a global trade and the printing industry led to an increased flow of people and ideas, allowing for a more widespread dissemination of knowledge. This in turn resulted in a more thorough questioning and analysis of the reality of the world. What was once just accepted as fact is now questioned, what was only poorly understood is now observed, and what was only supposed, tested. The recent advancements in areas such as mathematics, physics., or biology are undeniable, but the real revolution is the change in the perception and approach towards science itself and the way of understanding it. Systematic experimentation is the true scientific revolution, and it will surely change completely our conception of the world.

Military Revolution

This can spawn in any capital with a lot of military buildings and that has a population over 50,000. The historical location is Stockholm.

The continuous state of war affecting Europe in the 16th and 17th Centuries leads to a sharp increase in the size of armies, as a necessity born of the growing authority of competing absolutist regimes. The infantry is now armed en masse with flintlock muskets, greatly increasing their firepower and performance in battle by being deployed in the innovative line formation, replacing the old Pike & Shot. Those needs also affect the capabilities of the state administration as it continues to expand to handle the manpower and finances required by this increase in the size of the military. That also is spearheading the development of the supply chains required to feed and sustain armies, through intermediate depots that support the operational armies. The result of these advances would be none other than an upsurge of wars between increasingly militarized countries in the 18th Century.

Its one way to deal with the nobility I guess?

Age of Revolutions

The questioning of rights, authority and the world itself during the Enlightenment has led to the rejection of the Ancient Regime. As Absolutism gives way to Revolution kingdoms may have to make place for Republics.

Enlightenment

This spawns in a location with a university, and a high average literacy, where the owner has an “Innovative” Societal Value. The historical location is Paris.

The last century has seen Rationalism and Empiricism gaining an ever-increasing popularity among the great minds of the age. In letters, publications and coffee houses, kings, scientists, philosophers, and littérateurs are discussing the merits of tolerance, the scientific method, and the spreading of the ideals of the Enlightenment to all of humanity. From universities or courts of enlightened monarchs, expeditions are being sent to measure, catalog, weigh, and map the world so that we can better understand the laws that govern everything around us. Others discuss the laws that govern society and try to reach an understanding of the Rights of Man. Great projects such as the colossal undertaking of creating a complete encyclopedia of all knowledge or a complete index of all plants, animals, and fungi in the world are being pursued for the greater good of humanity. The Light of Reason has been lit and many will not rest until it has been brought to all corners of the earth.

Industrialization

This will spawn in any location with more than 250 building levels, and at least 20,000 Burghers, and where the owner has a “Capital Economy” Societal Value. The historical location is Blackburn.

The dawn of the 18th century gave rise to many new institutions as man's thirst for growth took hold. Advances in the field of production, and manufacturing as well as the introduction of complicated machinery will change the world as we know it on a global scale. The rise of the Industrial Revolution brings about international and lasting changes not just in commerce and business but in the fabric of society itself. Inventions such as the power loom and steam engines shall push the capabilities of mankind to its highest zenith yet.

Levée en Masse

This can spawn in any capital with a lot of military buildings and that has a population over 200,000, and where the owner has a “Defensive” Societal Value. The historical location is Paris.

Warfare is an ever-evolving concept, innovated and honed generation after generation. The 18th century saw the rise of powerful empires, each with its own ambitions. To satisfy the need for expansion and provide the fuel necessary to fulfill these ambitions, new nationwide conscription laws will be drafted and signed in effect, raising armies of all unmarried young men, the size of which will shape the course of history.

Next week we talk about what replaced the technology and national ideas system for Project Caesar.

This week we’ll talk about the ages and institutions, concepts that were first introduced in a patch to EU4. They were a convenient mechanic to make different eras feel different, but soon became too gamified with development ruining the institution game.

Every age introduces several new “REDACTED”, adds several possible new government reforms you can pick from, impacts the price stability of goods, and also has some direct impacts on every country. In every age, the amount of gold you pay for your raised levies will increase, and the size of the army you are expected to have increases. Each age is global in the world, but its true impact is gradual. There is no special mana you gain through achieving goals that you can use to stack modifiers with.

Ages of Traditions have passed, and we have just entered the Age of Renaissance here..

Each age also has three institutions that will spawn, each will unlock “REDACTED” and spread across the world.

We have designed the institution spawns to be more rigid for the first ages, and be more flexible in later ages, to guide the game in a certain direction. For those of you who dislike the dynamic spawning of institutions, you can put it in “historical” mode, and it will spawn in the same location every time.

There are only two options for this rule at the moment.

The spread takes time, as it can only spread through adjacent locations or across a single sealane, unless you have trade routes from a market center that has embraced it. The speed it spreads is also impacted by the literacy of the population. If you have embraced an institution, then it will spread in proportion to your control in your owned locations.

When an institution has spread to more than 10% of the population in your country, you can embrace it, meaning you will get access to the “REDACTED” it will give you.

As the technology system in Project Caesar is different than the one in EU4, missing an institution for a while is NOT a complete disaster, but more on that next week.

In later ages you can also start assigning a member of your cabinet to promote institutions in a province, which will then progress any institution you are aware of in the locations of that province. Promoting is heavily based on the burghers and the literacy of a location.

There are 6 ages in the game, and in 1337 we start in the Age of Traditions, and each age from there on lasts about a century.

It was the definitely the best of times...

Age of Traditions

Different societies have been established throughout the world for hundreds and thousands of years, and their foundations can be framed in traditions such as Legalism, Meritocracy, or Feudalism.

Legalism

We gave this institution the spawn point of Rome, even though there are plenty of places that could compete for it. Most of the Old World has this institution spread and embraced at the start of the game.

The theories behind Legalism have been integrating into Chinese societal structures for hundreds of years. The concept that pure idealism and domestic stability leads to a rich, prosperous state and a powerful army is deeply rooted in the forums of thought in the Eastern Asian domains. However, as merchants and migrants brought forth the exchange of ideas, the concept of Legalism made its way across the vast expanses of the Muslim world. There, it adopted the stance of a symbiotic relationship between heathens and believers in Islamic states. Legalism in Europe signified the rite of passage, from the dying grasps of the great Roman Empire to its remnant legal roots, many of which would later serve as the basis for new jurisprudence across the old continent.

Meritocracy

This has the birthplace in Beijing and at the start of the game, it has only spread through East Asia.

Many individuals of great prestige and in positions of power often chose to appoint those closest to them in influential spots. The advent of Meritocracy as an institution and a thought movement was largely popular in the courts of Imperial China. There, Confucius himself supported the notion that those who govern should do so on the basis of merit, not of inherited status. This led to the replacement of the Chinese nobility of blood ties to one based solely on meritocratic abilities. This institution's development would ripple across and beyond the borders of Asia and would eventually reach the royal courts of even European monarchs whose Nobles had a firm grasp on the mechanisms of power and authority.

Feudalism

This has its birthplace in Aachen, the capital of the Roman Empire under Charlemagne. It has spread in most of the Old World as well.

Over time, most societies develop a need for a common structure with stronger and more permanent institutions of government. After the fall of the Roman Empire, this need came to be filled by a number of institutions and customs that taken together are often considered to be part of the European Feudal system. For similar reasons, permanent government and societal systems have formed all over the world, some of which have roots that go far further back than Feudalism itself.

Have we show this image before?

Age of Renaissance

A new era of knowledge, arts, and progress is emerging due to growing interactions and institutions in the medieval societies affected by Pax Mongolica, the Islamic Golden Age, and the European Renaissance.

Renaissance

This institution will spawn soon after the age starts in a Northern Italian City with a University. The historical location is Florence.

Starting now in the 14th century, the wealthy and powerful in the Italian City states have been patronizing artists and scholars willing to explore the old Roman and Greek societies of their forefathers. As a cultural movement the Renaissance already encompasses most of the region and has had a profound impact on literature, art, philosophy, and music. Humanist scholars are also analyzing the society in which they live, comparing it to the ideals of the Classical philosophers. Renaissance Humanism has grown into a more mature movement, ready to permeate all aspects of society. A new ideal for rulers as well as those who are ruled is spreading as quickly as the early Printers can distribute copies of these new ideas. A true Renaissance Humanist is an expert on everything from politics and philosophy to art, textual analysis, music, and architecture. The Renaissance is now ready to reshape the world to better fit its classical ideals.

Banking

This can spawn in any town or city with more than 1000 burghers in Europe, North Africa or the Middle East, where the owner has a strong “Capital Economy” Societal Value. The historical location is Genoa.

Money lending has existed since metal-based coins appeared in Antiquity. However, it depended on some individuals and their family groupings or on the Ancient States. A shift occurred in the Middle Ages, encouraged by the renewed growth of long-range commercial activities on the Eurasian continent and its peripheries. Specialized moneylenders began to organize when Jewish communities started operating between the Christian and Islamic worlds. However, the boom of credit demand that followed the Crusades in the 12th century encouraged merchants in the Italian city-states to create larger structures for money lending, effectively founding the first Banking institutions, such as the Peruzzi and Bardi houses. More instruments were developed, like bills of exchange and debt bonds, and Banking dynasties such as the Medici, Fugger or Welser soon became as powerful as States.

Professional Armies

This can spawn in any location in Europe, which has some manpower produced, where the owner has a “Quality” Societal Value. The historical location is Paris.

Armies have existed since war was invented, many thousands of years ago. However, their form has changed over the centuries and different types of recruitment and organization have developed in different cultures and periods. In the Late Middle Ages, armies in a wide range of societies relied on levies based on the structures of feudal society, with knights and footmen forming a core that was levied seasonally. In some regions, however, states were powerful enough to finance standing armies, with professional soldiers who would be available for duty throughout the year. This system was also developed in Europe after the outbreak of the Hundred Year's War, being one of the main changes that promoted a Military Revolution in the Early Modern Age. Increasing the size and quality of Professional Armies, while finding new sources of revenue to finance them, soon became one of the main challenges for rulers around the world.

This looks like a nice place to add to the Spanish Empire!

Age of Discovery

At the dawn of the Early Modern era new continents are being mapped while feudal society is slowly giving way to centralized states. For an enterprising state this age can see the foundation of a worldwide empire.

New World

This will spawn in any port in Western Europe or North Africa, with more than 2,000 burghers, and where the owner has discovered the Azores and the West African Coastline. The historical location is Sevilla.

The discovery of the New World has heralded a new era not only for the colonizers and the colonized, but it has also led to the spread of materials and techniques as well as a realization of the vastness of the globe. As animals, crop types, silver and diseases spread across the Atlantic, the first steps have been taken towards a truly global economy. With foreign lands and people being mapped and documented, ideas as well as religious and philosophical debate are increasingly being colored by what we have found in overseas societies. Great minds feel the need to question what was once truth, and from Valladolid to Fatehpur Sikri, the nature of the world is now up for debate.

Printing Press

This can spawn in any location with more than 2,000 burghers, where the owner produces more than 5 paper and has an “Outward” Societal Value. The historical location is Mainz.

The ability to mass-produce the written word would revolutionize the spread of information and in many ways early modern society as a whole. Pioneered by Renaissance men such as Venetian Printer Aldus Manutius, the new art helped fuel the Renaissance by making the translated classics more widely available. Later the Reformation benefitted greatly from the ability to spread critical publications and translations of the Holy Scriptures. Now that Printing has matured as a technique and spread throughout Europe, hundreds of thousands of copies of everything from Religious and Political pamphlets to scientific treatises and instructions on how to behave are circulating the continent. With print shops growing evermore commonplace, rulers have found it hard to contain the new technique as the comparatively easy means of production means censorship can be sidestepped by moving business across a border or even just changing the name on a title page.

Pike & Shot

This spawns in a location, which has some manpower produced, where the owner has Professional Armies, more than 20 Army Tradition and a “Land” Societal Values, and have the gunpowder technology. The historical location is Innsbruck.

A new type of warfare began to develop at the end of the 15th Century, in the midst of the Italian Wars. The generalization of pikemen in the Late Middle Ages as an alternative to men-at-arms who could successfully face heavy cavalry charges was accompanied by the development of portable firearms, mainly matchlock arquebuses and muskets. The soldiers now adopt a new formation, in which the pikemen form a square, while the arquebusiers fan out to the sides and front, and seek cover behind or inside the square in case the formation enters close combat. This new type of formation, called Pike & Shot, was favored by German Landsknechts and Spanish Tercios, and was soon adopted by other armies, reigning supreme on European battlefields for nearly two centuries, until superseded in the early 18th Century by line infantry formations armed with new flintlock muskets mounting bayonets.

The heretic is trying to defend his heresy.

Age of Reformation

From East to West this is the age of religious conviction, debates and mass movements. In Europe, the protestant churches are entrenched while millenarianism takes hold of Iran and religious Syncretism shapes Indian society.

Confessionalism

This spawns in a town or city in Europe, which has a printing press, where the owner is Catholic, and the dominant religion is Catholic, and has a “Spiritualist” societal value. The historical location is Augsburg.

Catholicism has been regarded as a unitary entity for a long time, but the advent of the various Protestant Faiths has put an end to that. With the rise of a myriad of different interpretations of what the Faith should be, Christianity is all but united. But where before any deviance from the Church could be easily labeled as heretic, now the lines creating the differences have become blurrier at least. As such, there has been an increasing interest both for religious and secular authorities alike to clearly define the shapes of their specific confessions, enforcing their particular rules and views on all aspects of faith and life. This allows them a more firm grip on the faith of their population, but also increases the differentiation and thus animosity with all the other confessions.

Global Trade

This spawns in a market center in a city anywhere in the world that has among the most value of goods traded. The historical location is Lisbon.

Goods have been moved across continents since antiquity. But where this was previously limited to a set number of routes and goods such as the manufactured goods of India and China finding their way across the Indian Ocean and along the Silk Road, all trade is now increasingly becoming part of a greater world network. With the discovery of the Americas, sea routes around Africa and the crossing of the Pacific Ocean, local trade networks are being connected into one world-spanning interconnected web. Silver mined in the Andes is now being boxed and taken via Europe all the way to China and India. Iron mined and wrought in Scandinavia is being sold in West Africa by English merchants, and others are making a fortune just distributing cloth and spices within the Southeast Asian trade sphere. Local Indian merchants are investing in future European trade ventures. It may still be early to speak of a truly Global Economy, but surely the first seeds have been sown.

Artillery

This will spawn in any city in the world that has a gunsmith and a metal workshop, and where the owner has an “Offensive” Societal Value. The historical location is Constantinople.

The invention of gunpowder in Song China led to the development of a new device that would employ its firepower in warfare, the artillery. Although it spread throughout Eurasia in the 13th Century, its use as a common weapon system did not happen until the 15th century, as improvements in the cannon length and gunpowder recipe made artillery much more powerful, now posing a threat to stone-built castles and fortifications, the most common in Europe. Soon artillery would be used not only in sieges but also on battlefields, as smaller caliber guns now featured the mobility required to be quickly deployed and used. Its final development as a key warfare system would come in the 18th Century, especially after Napoleon perfected its use at key points during battles.

L'État, c'est moi.

Age of Absolutism

As governments wrest the absolute power in their countries from other parties, they are now able to devote themselves to the building of Empires. This is the age of the state, of rulers, and their armies.

Manufactories

This will spawn in any location with more than 100 building levels, and at least 20,000 Burghers, and where the owner has a “Capital Economy” Societal Value. The historical location is Derby.

While a number of technical innovations during the course of the 16th and 17th centuries have increased the output of production for some products such as iron or cloth to an extent, the biggest improvement in the field of production has come in the form of new forms of organization. By creating manufactories, often outside the city limits, merchant capitalists can both bypass the ancient guild laws that inhibit mass production, and pioneer ways to increase production through the organization and specialization of labor in one place. The forerunners of the later Industrialization were able to increase output by facilitating access to raw materials and mass organization of labor rather than by expensive new machinery. This is in itself a huge change over the often heavily regulated methods of old, however, and together with later technical advances this new mode of production will come to revolutionize society.

Scientific Revolution

This spawns in a location with a university, and a high average literacy, where the owner has a “Innovative” Societal Value. The historical location is Cambridge.

It is clear that the world is smaller now than ever before. The rise of a global trade and the printing industry led to an increased flow of people and ideas, allowing for a more widespread dissemination of knowledge. This in turn resulted in a more thorough questioning and analysis of the reality of the world. What was once just accepted as fact is now questioned, what was only poorly understood is now observed, and what was only supposed, tested. The recent advancements in areas such as mathematics, physics., or biology are undeniable, but the real revolution is the change in the perception and approach towards science itself and the way of understanding it. Systematic experimentation is the true scientific revolution, and it will surely change completely our conception of the world.

Military Revolution

This can spawn in any capital with a lot of military buildings and that has a population over 50,000. The historical location is Stockholm.

The continuous state of war affecting Europe in the 16th and 17th Centuries leads to a sharp increase in the size of armies, as a necessity born of the growing authority of competing absolutist regimes. The infantry is now armed en masse with flintlock muskets, greatly increasing their firepower and performance in battle by being deployed in the innovative line formation, replacing the old Pike & Shot. Those needs also affect the capabilities of the state administration as it continues to expand to handle the manpower and finances required by this increase in the size of the military. That also is spearheading the development of the supply chains required to feed and sustain armies, through intermediate depots that support the operational armies. The result of these advances would be none other than an upsurge of wars between increasingly militarized countries in the 18th Century.

Its one way to deal with the nobility I guess?

Age of Revolutions

The questioning of rights, authority and the world itself during the Enlightenment has led to the rejection of the Ancient Regime. As Absolutism gives way to Revolution kingdoms may have to make place for Republics.

Enlightenment

This spawns in a location with a university, and a high average literacy, where the owner has an “Innovative” Societal Value. The historical location is Paris.

The last century has seen Rationalism and Empiricism gaining an ever-increasing popularity among the great minds of the age. In letters, publications and coffee houses, kings, scientists, philosophers, and littérateurs are discussing the merits of tolerance, the scientific method, and the spreading of the ideals of the Enlightenment to all of humanity. From universities or courts of enlightened monarchs, expeditions are being sent to measure, catalog, weigh, and map the world so that we can better understand the laws that govern everything around us. Others discuss the laws that govern society and try to reach an understanding of the Rights of Man. Great projects such as the colossal undertaking of creating a complete encyclopedia of all knowledge or a complete index of all plants, animals, and fungi in the world are being pursued for the greater good of humanity. The Light of Reason has been lit and many will not rest until it has been brought to all corners of the earth.

Industrialization

This will spawn in any location with more than 250 building levels, and at least 20,000 Burghers, and where the owner has a “Capital Economy” Societal Value. The historical location is Blackburn.

The dawn of the 18th century gave rise to many new institutions as man's thirst for growth took hold. Advances in the field of production, and manufacturing as well as the introduction of complicated machinery will change the world as we know it on a global scale. The rise of the Industrial Revolution brings about international and lasting changes not just in commerce and business but in the fabric of society itself. Inventions such as the power loom and steam engines shall push the capabilities of mankind to its highest zenith yet.

Levée en Masse

This can spawn in any capital with a lot of military buildings and that has a population over 200,000, and where the owner has a “Defensive” Societal Value. The historical location is Paris.

Warfare is an ever-evolving concept, innovated and honed generation after generation. The 18th century saw the rise of powerful empires, each with its own ambitions. To satisfy the need for expansion and provide the fuel necessary to fulfill these ambitions, new nationwide conscription laws will be drafted and signed in effect, raising armies of all unmarried young men, the size of which will shape the course of history.

Next week we talk about what replaced the technology and national ideas system for Project Caesar.