A Decade of Prosperity

CHAPTER SIX

A Decade of Prosperity

1089-1099

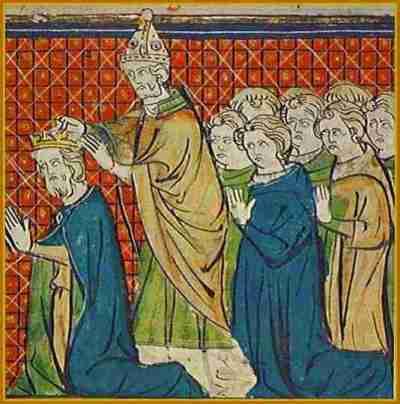

Bohemond had been crowned King. He who had been denied his rightful inheritance in Italy was now the undisputed monarch of the Holy Land. Undisputed among Christians, at any rate. Bohemond knew well that there were many threats to his rule from the followers of the false prophet, both within his borders and without. In order that Jerusalem not be viewed as a weak or forgiving enemy, the nobles of the realm agreed that the King should assert his position with a small but, hopefully, decisive war.

The King met with his council to determine which of Jerusalem's neighbours should be the target of the new campaign. The Emir of Damascus was wealthy from trade, and could pay a great many soldiers, while the Emir of Medina was a thoroughly determined guardian of Islam's holy places, and could rightly be expected to fight on to the bitter end. Seeking a quick and decisive victory, the King settled his sights on Petra.

The fabled city of Petra, carved from the cliffs by the ancient Nabateans

The Sheikdom had recently split from the Emirate of Amman, and was now vulnerable, with less than a thousand warriors at the Sheik's disposal, and little income to be spent on it's maintenance. The King crossed his army into the Sheikdom in March of 1089, and before June was out, had secured the Sheik's absolute surrender, absorbing the ancient city and the surrounding province into the Christian Kingdom.

The King had his victory, and it had been quicker and more decisive than he had even hoped. He had raised only a fraction of his own army, and had asserted his power in the region. It was not a grand victory to make even the Seljuq's shiver, but it had served it's purpose, to demonstrate that the Christians were here to stay, and would strike against those that threatened their borders without hesitation or clemency.

Mission accomplished, Bohemond appointed some minor officials to govern Petra in his absence, and returned to Jerusalem. Upon his return to the capital, the King was dismayed to learn of a minor outbreak of smallpox in Beirut, but nonetheless set about commissioning many new projects for the betterment of the realm. In August of the following year, the citizens of Acre rejoiced, for the city now had a fishing wharf and, furthermore, in the surrounding countryside land had been reclaimed from nature.

The following month, The Order of the Temple of Solomon sent another envoy to request land and castles, and were once again denied by the King. By December Bohemond had agreed to allow the Jews of Jerusalem to resume their tradition of usury, though he urged all good Christians against the borrowing of money.

In March of 1091, Queen Ingegerd gave birth to a fifth son, whom they named Alphonse, but two months later came less welcome news, as Bohemond's capable Marshall, Suhail ud-Dawlah, died of a fever.

The following few years were relatively uneventful. More projects were completed for the improvement of the kingdom, the smallpox epidemic in Beirut was brought to an end, and the kingdom's coffers grew more full with each passing month.

In January of 1096, Bohemond's eldest son Drogo came of age, and was deemed to now be old enough to take on adult responsibilities, just in time to command a regiment in the King's army against the treasonous Count Roger of Ascalon.The spring and summer of 1096 were spent campaigning against the disloyal Count, who finally gave unconditional surrender in August, resulting in Ascalon once again falling under direct control of the crown.

Prince Drogo at 16

Roger Morosini, Count of Ascalon

Prince Drogo at 16

Roger Morosini, Count of Ascalon

Upon successful conclusion of the campaign, Bohemond and Drogo returned to the capital, where the prince was wed to the Count of Darum's eldest daughter, Isabella, who had spent many years as a fosterling at King Bohemond's court. Prince Drogo was rewarded for his services to the crown with the Duchy of Jaffa-Ascalon. Shortly afterward, Queen Ingegerd gave birth to another daughter, Felicia. Meanwhile, King Bohemond's pet projects, a castle in Tiberias and a church in Acre, were completed.

The following year, Bohemond's second son, Stephen, turned 16, and was wed to Esperanza, daughter of the Duke of Castille.

March saw the start of another war, as King Bohemond sought to take advantage of the weakened state of the Emirate of Amman. The war took 3 months to conclude, and saw both Amman and Kerak added to the kingdom. Upon returning to Jerusalem, Prince Stephen was named Duke of Galilee in recognition of his valiant conduct in the war with the Muslims.

1098 saw the coming-of-age of Bohemond's eldest daughter Judith, who was then wed to the King's trusted new Marshall, Humbert de Villaret.

Before the year was out, a Templar House had been established in Jerusalem in the hopes that this would entice the knights of that order to assist the kingdom without demands of packages of land. Furthermore, a monastery was established in Acre, a city the King deemed to be vital to the success of the realm, and had spent countless pounds of silver on modernising.

But perhaps the most important event of the year, nay, the decade, took place not in the temples and churches of Jerusalem, nor in the sun-baked desert of Arabia, but in Rome, at the Basilica of St. Peter. The Holy Father, Pope Urban II, overjoyed with the successes of the crusades called by his predecessors against Jerusalem and Tunis, called the faithful to take up arms once more, in order that the Seljuqs might be driven from the ancient city of Antioch. While Bohemond was reluctant to commit forces to the endeavour, he did immediately recognise that it may provide an opportunity to weaken the Turk, and expand his own realm. Nonetheless, he determined to wait until more Christian warriors were in the region before making a move.

February of 1099 saw the coming of age of the King's third son, Prince Henry, who was soon wed to Blanche de Blois, a daughter of the Count of Sens. Prince Henry was also granted the Duchy of Jordan, while a training ground was built to provide more and better soldiers in Jerusalem, and a church was built to promote the true word of God in Amman.

The King's final act of the century was to place an extra tax on those in the realm who had benefited from the recent abundance of wealth. Bohemond fervently hoped to find a use for these extra funds in the service of God in the new century.