The Die Is Cast

The Soviet Union & The Cold War

The Soviet Union & The Cold War

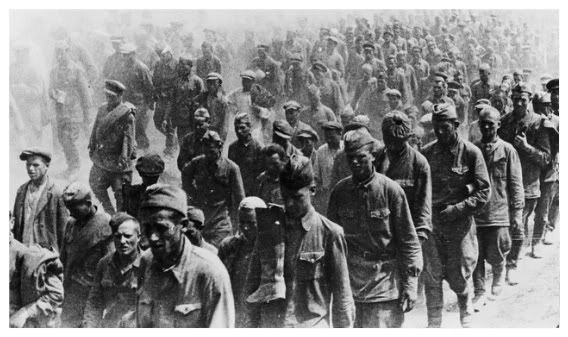

October 1945. The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, after four gruelling years of war against the forces of fascism and reaction, stood bloodied yet victorious. From Dresden to Sakhalin, from Petsamo to Tehran, the Red Army had weathered the most vicious of storms. However behind the pomp of Red Square and the medal-choked breasts of heroic soldiers, the Soviet Union was all but crippled. 20 million lay dead, while millions more were left homeless and hungry. Farms, factories, mines, mills, railways, roads, towns, villages, cities all destroyed across a thousand miles of apocalyptic battlefield. Iron production was at 27% of pre-war levels, steel at 45%, electricity output at 66%. In Baku and across the Urals, oil refineries untouched by war were left unmanned as valuable trucks, resources and engineers were poured into the war effort. The Ukrainian SSR had lost one in six of its population, the ‘Hero City’ of Leningrad, over a million. Across the once occupied western regions fighting still raged between loyalist partisans and thousands of nationalists, fascists and opportunists who had sided with Hitler’s invaders.

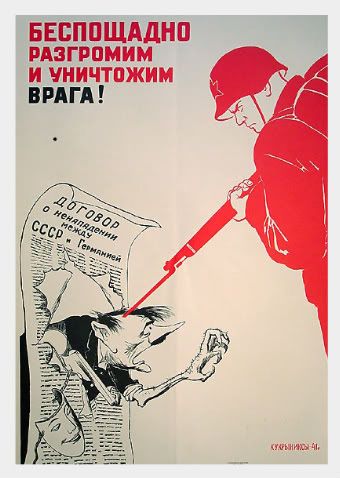

Domestically, the cost of the war had had a massive effect on Soviet society. In 1941, the Communist regime had been shocked by the joyous response the Germans had received in the Ukraine and former Baltic States. Seeing their armies crumble before the Nazi onslaught of Barbarossa, only the vastness of the steppe and the coming of a bitter winter had saved Moscow. Reduced mentally and physically to a shadow of his former self, Stalin had turned away from the internationalism and rigid dogma of Marxist-Leninism in order to rally a desperate people. Soon it was not the global proletariat under the hammer and sickle being lauded in the posters and film reels but the Russian nation and the cross, as patriotism and the Orthodox Church, once anathema, were drafted into the Soviet war effort. Meanwhile as vast swathes of industry were uprooted and re-established in the Russian heartlands, only the material and financial aid of the decadent United States bolstered the USSR in the dark days of 1942 and 1943. Even in the fields, the collective farm system, Stalin’s controversial pet project, was relaxed in order to appease the much-maligned peasant population.

Now with the war at an end, a new global balance of power had established itself. Long gone were the days of Lend-Lease and the amiable President Roosevelt. In their place stood the staunchly anti-communist Truman, leader of the most powerful nation on earth, and arbiter of the atomic bomb. The man who had praised the Nazi-Soviet war as a chance to kill off both, he held grave suspicions of Stalin and his intentions in Europe and the Far East. While the President’s less cynical advisors, such as Secretary of State James Byrnes, looked forward towards an international era of peace and democracy, epitomised by the UN Charter and Bretton Woods, Stalin saw his wartime gains as a concrete sphere, apart from the Americans and their allies. Already the establishment of a communist government in Poland in June had vindicated Truman in his own eyes. The implications were obvious. Following Japan’s surrender in August, the Soviet Union had been denied an occupational zone in the Home Islands, while in Korea, tensions between the Soviet north and US-administered south were already starting to show. Within only months of victory, it seemed a new bi-polar world was beginning to form.

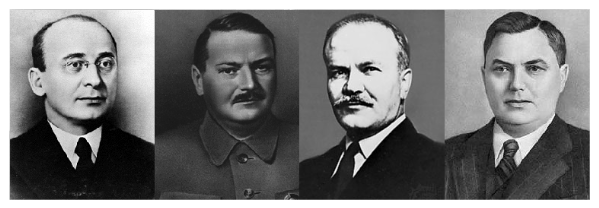

The chaos and turmoil of the war had left the autocratic Stalin an exhausted man. Faced with the grand task of rebuilding the nation for a second time in twenty years, a devastated population, vast new tracks of land in Eastern Europe and Asia to administer, and the returning spectre of ‘capitalist encirclement’, the generalissimo’s health deteriorated. Already living with a severe case of atherosclerosis due to heavy smoking and a poor diet, Stalin had suffered a minor stroke in May 1945, shortly following VE Day. On 9th October, after a late night of drinking and American cowboy films at his private dacha, the dictator had retired for bed. He never made it. The following morning he was discovered by an NKVD bodyguard, face down on his bedroom floor, still in uniform, having suffered a fatal heart attack. By the time doctors had arrived, it was far too late.

Stalin was dead.

---------------------------------------------------------

Author's Note: All the stuff relating to Stalin is true, 1945 did see him suffer several strokes and heart attacks. He even loved Westerns, though relied on an interpretor due to a lack of subtitles on the stolen films.

Last edited: