The People’s Flag: A History of the Union of Britain, 1925-2010

- Thread starter Meadow

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Will we be seeing another update soon?

Also, how are things going in the Balkans. That is always a messy area in Kaiserreich (more because of the inadequacies of the HoI2/AoD/DH engine). Bulgaria is probably very vulnerable and could easily collapse if the whole of the Belgrade Pact dogpiles it. That would leave the Internationale in a very interesting position; do they support the Iron Guard to provide another front for Mittleuropa or do they maintain total ideological rigidity? Bulgaria collapsing could have very serious consequences for Germany, as it would cut it off from of its oil supplies.

Also, how are things going in the Balkans. That is always a messy area in Kaiserreich (more because of the inadequacies of the HoI2/AoD/DH engine). Bulgaria is probably very vulnerable and could easily collapse if the whole of the Belgrade Pact dogpiles it. That would leave the Internationale in a very interesting position; do they support the Iron Guard to provide another front for Mittleuropa or do they maintain total ideological rigidity? Bulgaria collapsing could have very serious consequences for Germany, as it would cut it off from of its oil supplies.

There'll be an update today or tomorrow.

As for the Balkans, they will be covered during the war, and you may get some hints as to the situation there during the next International Interlude.

As for the Balkans, they will be covered during the war, and you may get some hints as to the situation there during the next International Interlude.

There'll be an update today or tomorrow.

As for the Balkans, they will be covered during the war, and you may get some hints as to the situation there during the next International Interlude.

Excellent! Oh by the way, did you know that if Edward VIII had been king, one of his royal descendants might have been David Cameron? (oh the hilarity that could have ensured :rofl

There'll be an update today or tomorrow.

As for the Balkans, they will be covered during the war, and you may get some hints as to the situation there during the next International Interlude.

Assuming it is true of course, updates for this AAR have a nasty habit of lagging terribly behind (not that I'm (really) complaining, they are of the highest quality). I'm on the brink of doubling all of Meadow's estimates for how long until the next update.

Assuming it is true of course, updates for this AAR have a nasty habit of lagging terribly behind (not that I'm (really) complaining, they are of the highest quality). I'm on the brink of doubling all of Meadow's estimates for how long until the next update.

You have good cause to say so. However, this next update has about 3000 words done and will be finished by this evening. Hurrah!

‘A ragtag pack of bandits, novelists, halfwits and drudges. If these are the best men our once-Sceptred isle can provide, we shall be in London by 1942.’

Winston Churchill, Minister for War, Sea and Liberation, ‘His Majesty’s Government’, 1 October 1940

Winston Churchill, Minister for War, Sea and Liberation, ‘His Majesty’s Government’, 1 October 1940

A Very British Emergency

John Durham

The Chairman of the Congress of Trade Unions, Oswald Mosley, outlining his intentions to the Emergency Executive

Britain was stunned. During the time it took for Undersecretary Wilson to stagger towards a seat at the end of a pew in the Congress Hall, the room erupted into a chorus of panicked shouts, angry cries and screams of terror. It was obvious to everyone that war was the Canadian intention, and as far as they knew the Union was completely unprepared for such a conflict.

Mosley rose from his seat, visibly supporting himself on the arm of the Chairman’s chair. With a sudden, loud banging of the gavel, he called the Congress to order. ‘Comrades,’ he began, apparently quite oblivious to the indignant Arthur Horner who was still stood at the speaker’s podium, ‘it is clear that events beyond the control of this body have moved past a point of no return. I move that Congress be adjourned for the day, and that the Central Bureau accompany myself and Comrade General Secretary Horner to the meeting rooms to assess the situation.’ There were mutters of dissent and cries of ‘shame!’ from some corners of the room, but the mostly disoriented and largely pro-Maximist Congress relented quickly. ‘Nobody really had any idea what was going on – the wireless and The Chartist had made no mention of the Iceland situation. I was one of those who wearily raised my hand to support the adjournment. It wasn’t clear at all what would happen next,’ wrote Margaret Cole.[1] As the Central Bureau moved to the meeting rooms, someone noticed that Harold Wilson, the fateful messenger, had passed out. He was not alone.

‘The fear in everyone’s eyes as we brushed past them to head to the meeting rooms was evident,’ wrote Eric Blair, on his way to join Mosley in his capacity as Commissary Without Portfolio, ‘and we suddenly all felt very small, like children. Our little revolution seemed somehow trivial. The Catholic Wars and the conflict of the American Brigades (who had arrived home to a shower of praise a few months before) had not ever threatened our existence. We were a young, socialist nation with few friends, and this had never been clearer than now. I passed Niclas y Glais – he had aged terribly since 1936. He looked at me with a distant fear in his eyes. Everything – the Agricultural Revolution, the redevelopments, the squabbles over the Transportations – had become irrelevant in the space of twenty minutes. The Royalists threatened us with total destruction, and we apparently had no place to which to turn. If we acquiesced to their blockade, they would surely seize Iceland and quash the revolution there, then use the bases to stage an invasion of Britain. If we tried to break the blockade, we would be plunged into war immediately and nobody apart from Oswald, the Chiefs of Staff on the Defence Committee and perhaps Clem had any idea whether our forces were ready for that. Our armies had some strong, experienced units thanks to the various entanglements we had involved ourselves with since 1936, but the Navy was still a highly confidential matter and the Republican Air Force had an impressive array of new fighter aircraft but a deficit of well-trained pilots. But the Canadians had played their hand now, and surely were therefore ready to go to war now – if we appeased them to gain more time for ourselves, we would surely be granting them all the time they would need to refine their invasion force. With all these thoughts flying around my head, along with those usual fears a man has for his family – Eileen had told me she was with child earlier that week – I approached Meeting Room 7A.’[2]

Blair, along with the rest of the Bureau, was surprised by what he found in his Chairman’s behaviour when his comrades had assembled. Standing with his back to the group with his hands folded behind him, Mosley spoke calmly and apparently rationally while looking out of the window into the street. ‘It will be necessary, I feel, to invite those members of Comrade Horner’s… faction into this meeting. Unity is vital in a time like this. Comrade Horner, perhaps you could fetch them from the Congress floor. I have already asked my personal secretary to contact some other figures whose presence I feel will be useful.’ The medium-sized meeting room quickly became an exceptionally awkward place to be, with Commissaries milling around making small-talk and, very quietly, discussing what on earth would happen next. Bevan was deep in thought, muttering to himself every so often, while Attlee cornered Blair and began an uncharacteristically testy rant regarding the state of ‘the books’ (Attlee’s preferred shorthand for the country’s economy). Ernest Bevin stood alone in a corner, flabbergasted at what he had permitted to happen. Others steered well clear. Edwin Gooch lit a cigarette and puffed furiously. Annie Kenney wrung her hands and paced in silence, while William Gallacher and Tom Wintringham spoke feverishly about the suspected strength of the Canadian and Royalist armed forces – Gallacher’s spy networks had failed to make particularly significant inroads across the Atlantic. Within an hour, Horner’s party had arrived. G.D.H. Cole, Harry Pollitt, Niclas y Glais, J.B. Priestley, Lewis Jones and newcomer Christabel Pankhurst sat with the General Secretary at one end of the lengthy conference table. The rest of the meeting congregated around them and, eventually moving from the spot to which he had seemed rooted since he entered the room, Mosley sat at the head of the table.

‘Welcome, Comrades. I am sure none of you wish to delay our decision-making process any further, so I would like to –’ Mosley was interrupted by a rap at the door and the appearance of his secretary, Mrs Hardie. She informed him that the guests he had invited had arrived at Congress House. Mosley took this in stride and continued speaking. ‘Comrades,’ he began once more, ‘many of you have scoffed at my appeals for unity in the past. I will admit that they have, in these divided times, sounded often hollow and insincere. But gentlemen,’ he said, reverting for a moment to his unfortunate habit of using pre-revolutionary language in high-pressure situations, ‘I ask you now to accept my word that as our Union teeters on the brink of war, I am prepared to do everything that is necessary to preserve it. Comrade Horner, I hope you will be by my side in this. Comrade Blair, I know that Britain may rely on you in whatever role you take. Comrade Attlee, your management abilities might just save millions of British lives. Comrade Bevan, your construction of Britain’s infrastructure has thus far been impeccable. You may now have the honour of fighting for what you and your fellow workers have built. To those of you from our armed forces – Comrades Wintringham, Wedgwood-Benn, Kirke and Chatfield – I say that I need not personal loyalty from you, or anything quite so reactionary. But our country needs its finest men ready, armed and willing. I have every belief that this can be accomplished with you at the helm. To the rest of you,’ he continued, gesturing to Annie Kenney and the various members of Horner’s party, ‘I know your skills and revolutionary fervor will serve our country well in the coming time. But, Comrades, I hope that you will permit me one last unilateral decision.’ There was a ripple of disapproval from the table, starting with Cole, but Horner quietened them down, his eyes fixed on Mosley.

‘Thank you, Arthur,’ Mosley began, ‘Comrades, you will no doubt agree with me that what this Bureau lacks is a Commissary for War. If we are to find ourselves embroiled in a conflict for our very survival, we will need someone with fire in his belly, the cause of labour in his heart and the machinations of a genius in his brain. I hope that you will therefore agree with my choice for this position, even those of you who, like me, have had more than your fair share of troubles involving him. Mrs Hardie,’ he called, ‘please send in the Commissary for War.’ All eyes turned to the door. It opened, and the silence that fell was deafening. The tall, dishevelled man in the doorway looked Mosley in the eye.

‘Alright, you bastard. What do you want?’ said James Maxton.[3]

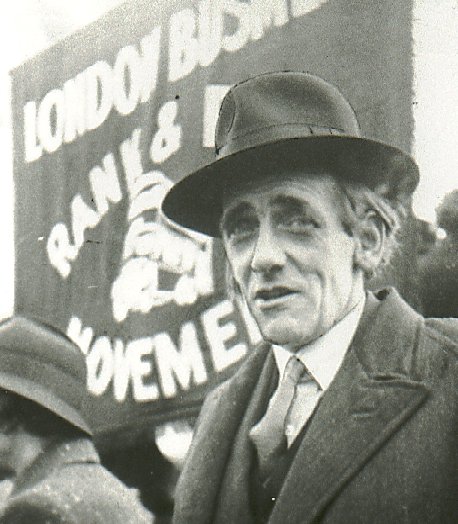

James Maxton, photographed while clandestinely attending a protest march in June of 1940

The situation was quickly explained to Maxton, who had already only agreed to enter the building housing his greatest political enemies when he had been informed by Mrs Hardie of the Canadian blockade. Maxton sat, almost crumpled, in a chair at the end of the room while Mosley calmly laid out his proposal for the size, remit and responsibilities of the Commissariat for War. Blair noted that Maxton had not aged well since he had last seen him in person. His cheeks seemed more hollow and he was significantly thinner. Years of marginalisation and arrest (but never quite imprisonment) had damaged the man’s body but not, as would become evident, his mind. As the man he hated spoke, Maxton’s eyes widened as he took in all of what was being said. The two great rivals stared at each other throughout Mosley’s short speech outlining the situation and what was expected of him. When the Chairman had finished, the Clydeside firebrand removed his hat. With an infinitesimal nod, he agreed with the proposal, with one condition. ‘I pick my own people,’ he said, ‘no point having me if you hamstring me with your lackeys. No offense intended, Eric.’ Blair took none, or so he wrote. With the Commissary for War now on board, Mosley turned, once more in his unnervingly soft ‘administration voice’ as Blair called it, to the matter of internal security. ‘We doubtless have many spies in the country,’ he asserted, ‘as well as many portions of the mercantilist classes that would easily back the Royalists over the Revolution. Comrade Beckett has made excellent headway in building an internal security department that is able to monitor these elements to some degree. However, Comrade Beckett’s military experience suggests to me that he should be appointed as a member of the Forces Committee – Comrade Wedgwood-Benn, as the current Chair, do you have any objection to this?’ No objection was received, but Tom Wintringham was notably fuming. The rotating chair system for the Chiefs of Staff meant that even though Wintringham was in overall command of the Armed Forces, decisions about the makeup of their structure were presided over by himself or Kirke, Chatfield or Wedgwood-Benn, depending on the time of year. The move was almost certainly a means for Mosley to marginalise Wintringham even further.

With Beckett also satisfied, Mosley introduced the meeting to his other ‘guest’ who had been waiting outside – Clive ‘Jack’ Lewis, an occasional novelist who had become fascinated with the concept of purging reactionary elements from the Union of Britain and had called for such in short stories distributed in pamphlet form. His most famous work, The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe was about ‘the witch’ (Queen Victoria) and her lion (the Empire) stalking four children forced to work in horrid conditions in a Victorian dystopia until they hid in a wardrobe, only to find it a portal to the Union of the 1930s. An apparently jolly man from his appearance, he entered the room in a characteristically ill-fitting suit and with what was left of his hair somewhat out of place. Mosley had come into contact with him through Beckett (who had made him his deputy after he broke up a Royalist sabotage network that had been operating near Bristol) and had been impressed by the latter’s recommendations that the quirky novelist be his replacement. Blair noted at the time that ‘although it was the first time I laid eyes on him, something about him unnerved me. He seemed outwardly pleasant, much like a popular uncle, but his eyes were slightly too large for his head, and always seemed to be wide open as if taking in every detail on one’s face. I was instantly without doubt that this man was capable of a frightening amount of cruelty.’ His words were more prophetic than he knew.

Nevertheless, the appointment was passed by the assembled men without much difficulty. The men and women at the table who did not have official positions waited to see what would happen next. Some thought they would be asked to leave. However Mosley, magnanimous as he was on this fateful day, offered each and every one of them a job in the new or existing departments. Christabel Pankhurst was flabbergasted to be offered the post of Deputy Commissary for Foreign Affairs – the first woman to reach such a diplomatic height in Europe. Lewis Jones joined Maxton at the Commissariat for War, while Niclas y Glais and J.B. Priestley were offered the roles of Undersecretary for Particulars and Commissary for Information respectively. Only G.D.H. Cole and Harry Pollitt were left out of this process, but Mosley insisted that this was merely because they would be offered new positions as the meeting went on. Glancing at Arthur Horner to receive his approval, Mosley put forward his final motion for this stage of the meeting before the Iceland matter was to be tackled by those assembled. In light of the circumstances, this new expanded Central Bureau was to be termed ‘the Emergency Executive’ and would act in accordance with the wartime powers granted to such an executive in the Constitution of the Union of Britain. Maxton, who had himself played a part in writing those provisions, supported the move, as did Horner. With the three powerbrokers of the meeting in agreement, it seemed inevitable that the motion would pass, and pass it did, but not before an amendment calling for ‘some provision of democracy’ to be instated had been tabled and passed by y Glais, Cole and, interestingly, Blair. As the clock struck eleven, Mosley banged a small gavel and called the first meeting of the Emergency Executive, with himself as its Chair and Horner as its General Secretary, to order.

Clive ‘Jack’ Lewis, Britain’s Commissary for Internal Security as of 1940

The first priority of the new Executive was to achieve détente between the parties involved on the subject of agricultural reform. Horner and his faction made it clear after Mosley welcomed them to the meeting that threat of war or no threat of war, they would have no part in any body that was not prepared to rectify the ‘gross mistakes’ committed in the preceding fifteen months, and duly tabled their immediate resignations if the meeting proceeded without any agreement on the topic. Rhetoric against the Second Revolution had been stepped up, with Cole's Guild Socialist League giving out reams of pamphlets criticising the nationalisation of the land as 'Enclosure all over again' and, most recently, a group named 'The Heirs Of Winstanley' had begun taking violent action to seize control of state farms and live on them in early-Revolutionary-concept (or indeed Civil War-era) communes. John Beckett, the now-former Interim Head of Internal Security, gave a testy report of the latest actions of these ‘terrorists’ when Cole attempted to rationalise their behavior. ‘Is it “understandable”, Comrade,’ he asked, ‘that two Land Officers would be taken from their homes in the dead of night and shot in the middle of a wood? That fourteen women and children died in the burning of a labourers’ compound just last night?’ Cole was shocked by the second figure and quickly backpedalled, but insisted that the way to prevent this discontent was to moderate the policies of Comrade Gooch’s department and seek compromise. All eyes turned to Mosley to see if he agreed with this prognosis. After a long pause, during which Mosley seemed to search the ceiling for an answer, he gave a slow reply in which he agreed to ‘reconsider’ elements of the Second Agricultural Revolution.

Three hours later, an exhausted Arthur Horner was feverishly writing down the decisions that had been taken. The general consensus was simple and two-layered: Mosley’s claim that he had only intended to make Britain as self-sufficient as possible because of the risk of a blockade by Canada or Germany was accepted. So, too, was his logic that if ‘fortress Britain’ was to succeed as a strategy, ‘the fortress will need more than a kitchen garden’. Nevertheless, as a concession to Horner, Cole and Maxton (whose talent he and the country desperately needed), nationalised agriculture was accepted to be ‘not viable at this time’. The protests of Edwin Gooch were diminished by an assurance that although the Second Agricultural Revolution programme was to be halted ‘for the duration’, existing state farms would continue to be expanded in size and the recently-formed Land Army would be presented as an option to conscientious objectors if conscription was introduced at any point during the war that was now, it seemed, coming sooner rather than later. This would serve as a suitable replacement for the steady flow of Transported individuals from the cities. As a further concession to the Guild Socialist League, Cole was to become an undersecretary in the Commissariat for Agriculture and liaise with y Glais at the Particulars Division (a thinly-veiled propaganda department) to develop the so-called ‘Dig For Victory’ campaign. Britons would be encouraged to ‘take the mantle of the Levellers’ and turn swathes of public land, be it parks, Downs or even one’s own garden and form farming co-operatives to gain as much food as possible from ‘every square inch of our green and pleasant land’. It was a sign that Cole had become happy with the situation – happier than he had been for months, in fact – when he took Mosley aback with an apparently non-negotiable demand. When Mosley cautiously enquired as to what the demand was, Cole broke into a smile and laughed, ‘We shall need a great many potatoes.’[4] Finally, the matter of democratic accountability for the Executive resurfaced as part of the agricultural détente negotiations. As Horner and y Glais expressed particular discomfort with the present image of a ‘cabal’ running the country ‘from some bunker, out of touch with our fellow workers who will soon be suffering’, it was Eric Blair who, after four years on the peripheries of Mosleyite rule, finally played his hand. Proposing that, to combat the limitations and unwieldy scale of the Congress of Trade Unions when it came to governing during a lengthy crisis, a more regularly-assembled body be formed ‘for the duration’. Suggesting, seemingly off the top of his head, that it be named the ‘Council of British Workers’ and that it could be made up of one representative from each of the Syndicates represented in the CTU (which would amount to approximately one hundred and sixty members), he concluded that in order to avoid associations with reaction and the sordid local governments of the old regime, the term ‘Councillors’ was inappropriate. After a stunned silence at what was surely the longest outburst Blair had ever given out in such a large meeting, Mosley asked what he believed would be appropriate. After a moment’s consideration, Blair put forward that, in keeping with British Revolutionary history, these representatives could be termed ‘Agitators’.

And so it came to pass that out of a debate on agricultural reform, an indirectly-elected body of consultation (legislation was out of the question, as ever) was born. To be housed temporarily in the former House of Lords (paradoxically, the hypocrisy of the name ‘House of Commons’ had disgraced the chamber more than the unabashed name of the former upper house, red leather was deemed more suitable than green, and besides the Commons had been turned into the main hall of the Museum of the Old Regime in 1927 and the Royal Carriage now hung from its ceiling) and overseen by Agitator-in-Chief Blair (the ever-modest Blair had put forward the ailing Tom Mann for the position, but had been quick to agree that Comrade Mann was too old to take on such a position now – suspiciously quick, in Horner’s eyes), the Council of British Workers was to be proclaimed to the CTU the following day, and elections carried out immediately among the delegations from the Syndicates present.

The former House of Lords, shortly before the Royalist imagery was stripped out and replaced with stylized hammer and torches and a mural depicting the Battle of Westminster during the Revolution

With détente achieved with regards to agriculture, the Emergency Executive turned to the matter of the general situation regarding foreign relations. There was a long, poignant silence in which all eyes fell on Ernest Bevin, and it was in a low, controlled voice that Mosley ‘suggested’ that it would be most appropriate, in light of the unchecked escalation of the Iceland Crisis, for the Commissary for Foreign Affairs to offer the Committee his resignation. Bevin, who had been in a stunned silence since Harold Wilson first staggered onto the Congress floor, gave a muted murmur of agreement and asked if he might therefore be excused from the meeting. Arthur Horner, however, raised a hand and signaled for the burly Gloucestershire dockworker to keep his seat. ‘I think that, in light of the Commissary’s years of service and clear ability, it would be a great shame to lose him at this trying time,’ he said, suggesting Bevin remain in the meeting in case a ‘more appropriate use’ for his talents as an organiser of labour could be found. This was met with agreement and the elephant in the room of Bevin’s incompetence in failing to properly engage with the Crisis was somewhat diminished in size. Mosley quickly seized control of the discussion and handed out documents outlining his plans for a ‘Commissariat for Solidarity’, a sort of consultative bureau that helped Trade Union leaders with any problems or suggestions regarding quotas. Mosley had planned to introduce it during the next Three Year Plan but matters had taken an unexpected turn and it seemed only right to encourage more co-operation immediately, given the circumstances. After assuring Annie Kenney that her position as Commissary for Female Workers would remain unchanged and inviting Harry Pollitt to head the new Commissariat for Solidarity, Mosley turned with a smile to Ernest Bevin and told him he would be intensely valuable in a Deputy role answerable only to Pollitt and Mosley himself. Bevin accepted in a fluster, presumably still terrified that he was going to be shot the moment he got home, but it was clear to all present now that the matter was resolved.

The matter of Bevin’s replacement was a more complex one. G.D.H. Cole, though begrudgingly present and a former holder of the position, declared himself uncomfortable with foreign affairs and said the Dig For Victory campaign would take all this energy. Bevin’s deputies were all young, with his chief undersecretary Harold Wilson barely into his twenties (he had got the job through, Bevin admitted, admirable brilliance). Ambassador[5] to Bengal R.H. Tawney was suggested by Eric Blair as a candidate, but Mosley vetoed the idea as he suspected (correctly) that Britain would soon need a respected and longstanding voice on the subcontinent, and Tawney was much-beloved by the Bengali people and their government. It was after a quick discussion and quicker rejection of the then-ambassador to France, Herbert Henry Elvin, that a decision was reached. Elvin was, in any case, highly involved in the growing maelstrom of the Third Moroccan Crisis, and had to give platitudes on a daily basis to the French government as it stepped up its support for the Syndicalist rebels in Marrakech.

In retrospect, Stafford Cripps, British ambassador to the Socialist Republic of Italy, was an inspired choice to define Britain’s foreign policy. Well-spoken and of aristocratic stock, he was also a committed orthodox Marxist who had refused to involve himself with the various factions that had dominated Union politics since 1925. Thanks to these two qualities he was perfectly domestically acceptable while being not inappropriate for the various dealings with the Royalists, Imperialists and, if it should come to it, Russians that Mosley anticipated. He arrived at Congress House a day after receiving news of his promotion via telegram, and left instructions for his deputy, Samuel Miliband,[6] to succeed him in Rome.

Cripps being incommunicado until he arrived in London on 28 September, it was left to the members of the Emergency Executive to formulate the British response to the Canadian blockade of Iceland themselves. The situation was alarming – over eight hundred British citizens, more than half of them civilians, were posted in the island nation and the government had recently fallen to the newly-formed Congress of Icelandic Trade Unions after riots over food prices. The Canadians had sent a blunt telegram to London declaring that Britain’s obvious attempt to gain a ‘new Atlantic base’ against the rights of self-government desired by Icelanders was unacceptable and that the blockade would send freighters ashore at 0600 local time the next day to collect all British personnel and take them as far as Scapa Flow. If British personnel did not board at this time, the Canadian government accepted no responsibility for what would happen to them during its planned ‘restoration of the democratic government’ which it intended to perform ‘with all necessary force’. Bevan quipped that it was nothing more than ‘the most violent eviction notice in history’, and it was agreed by all parties that the real intention of the Canadians (and their ‘Exile’ puppetmasters) was to gain the base of Reykjavik for themselves for possible future operations against Britain. Bevin sheepishly informed the committee that one benefit he had agreed to when keeping half an eye on the agitation operations that Britons had undertaken in the Icelandic capital had been basing rights that the Union would have enjoyed for the directly inverted reason. Mosley cut through the ensuing chatter by saying that, while he had no desire to take the country to war, this was a clear violation of British rights to the sea and international solidarity. In addition, over eight hundred British lives had been put at risk and held hostage by a foreign power. There could be no alternative but to reply to the Canadian telegram with an ultimatum, published in The Chartist and forwarded to the Canadian equivalent newspapers, that demanded the lifting of the blockade and the withdrawal of all Canadian military units from Icelandic waters.

‘Battersea Power Station At Sunset’, a photograph taken, entirely coincidentally, on the twenty-sixth of September 1940. It became a powerful symbol of the industrial but noble peacetime serenity Britons were striving to restore

As the couriers left the room and made their way to Broadcasting House to make the ultimatum public to both the Canadian and British peoples, there was still much to discuss. Determining the state of the armed forces was established as the paramount priority. As this vote passed, Clem Attlee raised a hand and noted that it was now three o’clock in the morning, and suggested an adjournment of the meeting. Mosley agreed, but declared he himself would meet with the members of the Defence Committee to determine the strength of the Union and, if the situation ended as feared, how best to relieve the Britons on Iceland by force.

And so, as the most transformative twenty-four hours in the Union’s history came to an end, and the sun rose over the twenty-seventh of September 1940, the telegraph wires of Europe and the Atlantic became wild with traffic. Around Britain, men and women slept peacefully in their beds, unaware of the changes that their leader would announce via the wireless at eleven o’clock the next day. In the pews of Congress House, Trade Union leaders and their fellow delegates stretched out to a far less easy sleep, but most of them found themselves unable to rest fully before doing at least a brief set of calculations regarding how to ready their workers, their families and their communities for the inevitable. In meeting room 7A, Eric Blair requested leave from the meeting to plan his speech to the Congress floor the following day in which he would establish the Council of British Workers. Bevan and Attlee retired to Britain House to prepare their departments. Pollitt and Bevin followed to begin building their department. J.B. Priestley took a cab to Broadcasting House and requested a small office in the basement, which by February 1941 would become the nerve centre of Britain’s Commissariat for Information. James Maxton remained with Mosley and Horner as the meeting with the Defence Committee began, but asked to be excused for a few minutes to contact his wife. According to his diaries, he did not in fact contact his wife, but went straight to the John Maclean memorial outside Congress House. ‘I know you’ll think me a fool, a traitor and sellout for getting into bed with that bloody Baronet, John,’ he said, allegedly quite audibly, ‘but I know that if you were here now, in these shoes, facing a choice between siding with him and fighting to keep this republic alive, or doing nothing while the bastards tear down everything we and the people of this country built, you’d be in that meeting too. So I don’t want you turning up in my bedroom like some Red Jacob Marley, d’you hear me, you old bastard?’. He returned to the meeting fresh-faced and sharp-witted, and together he, Horner and Mosley worked through the night, none of the three giving off the slightest indication of tiredness.

The members of the Emergency Executive continued to go their separate ways for the time being. Commissary for the Intelligence Bureau William Gallacher scheduled a meeting with T.E. Lawrence and his adjutant Ian Fleming about readying their Revolutionary Exportation Directive for immediate deployment in Iceland. Annie Kenney sat down at her typewriter and began to write well over a hundred letters, each one beginning with the word ‘Sisters –’. G.D.H. Cole jotted down some designs for the Dig For Victory campaign’s posters in his notebook as the night’s last train on the Northern Line pulled out of Congress House station. A few carriages behind him, Jack Lewis leant back in his hard seat and made a mental note to do something about the two loudmouthed servicemen sitting nearby who had clearly had too much to drink. Careless talk costs lives, after all. Christabel Pankhurst couldn’t quite believe the size of her office as she sat down in a chair behind the desk of the Deputy Commissary for Foreign Affairs in Britain House. Meanwhile, on a train hurtling across southern France, Stafford Cripps put aside a newspaper calling for war with Germany over ‘the Moroccan insult’ and turned his mind to the notes he had begun to make about securing French support against Canada. Tomorrow was going to be a thoroughly interesting day.

[1] Margaret Cole, Our Darkest Hour: Memoirs from the War (London: Penguin Publishing Cpv., 1951) p.9.

[2] Eric Blair, Keeping The Red Flag Flying (London: Onward Books, 1955) p.42.

[3] This section is based on primary accounts of the meeting, mainly the Blair book referenced at footnote [2].

[4] G.D.H. Cole, The Hammer, Torch and Spade (Peterborough: Orchid Publications, 1961) p.14.

[5] British Special Representatives abroad had been formally re-designated as Ambassadors in one of the first acts of the Maximist administration in 1936.

[6] An émigré from the German client state of Flanders-Wallonia, Miliband had arrived with his family shortly after Britain’s ports re-opened in 1927. An excellent grasp of Marxist theory and knowledge of six European languages had seen him quickly adopted into the diplomatic service after he gained British citizenship in 1931.

Too much politics, to few war.

Sorry you feel that way

I can't help but to shiver when the Police-state side of the UoB rises to the surface....

And now for some comments from my alter ego on alternate history forums; teg;

I just realized that I implied I admired Oswald Mosley for his actions in OTL; I do not. I admired him for his actions in this update.

This update pleases me. And to mark the end of this volume and the end of peace, I am going to do a review of the whole book so far.

Volume I

The Violent Death of Illiberal England:

A very good start. It is nice to see that the Union is not a totally Stalinist state and is willing to take an objective account of its history and admit the revolution wasn't totally good versus evil.

The Inaugural Congress

More obviously patriotic history. You do however make the politics quite interesting (which is difficult).

The Royalist Exodus

An interesting update. I do find the execution of Haig particuarly disturbing (it does show the Union really does have a very unpleasant side to it); but then again he doesn't have the 1918 campaign and the Entente victory in the First World War to redeem himself.

I sincerely hope for the sake of Britain that they are able to persuade themselves and their Allies to be as gracious to the Germans as they have been to their own monarchy.

One sad thing is that without the aristocracy, places like Longleat Safari Park and the Romney-Hythe and Dymchurch Railway aren't going to exist. Oh well.

Carving Out a Place in the World

This was the most interesting update so far IMO. Germany is probably going to live to regret not destroying the British in 1925, when they were weak. The relationship between Britain and the reactionary powers of Ireland and Germany is intriguing; only Ireland seems to recognize the Union de jure, while Germany is doing it de facto.

I also liked the occasional hints of the future; it is clear that the Third Reich is going to be destroyed at some point (if it wasn't already immedieately clear)

The Congress Concludes

And now for the hard part. This update didn't leave that much of an impression to be honest; mostly because it was more politics. It would have been good if you could have wrapped up the Congress in the first update.

One key question in my opinion is what will happen when the traditional rights of the army start to get infringed (partially answered in Volume II). Montgomery is going to put Mosley in a difficult position after the war; he doesn't owe his position to Mosley or the Maximists. While Mosley can probably bully or threaten his fellow Syndicalists into submission, it would be considerably to do it to a famed war hero.

The End of Empire

Good to see that Germany didn't suffer a total brain-freeze and grabbed most of the empire that wasn't already gone. I can only wonder at the fate of Mittleafrika and the other German colonies when the war is over (again, it is implied they will be freed after the Second Great War).

Staying on Track

Very amusing, flipping Clarkson into an insane left-winger (although I imagine that the Union has very different beliefs with regards to left and right wing).

However, there is a major issue in this update. WHAT HAVE YOU DONE TO THE NAMES OF BRITAIN'S ENGINES? I hope that when the railway preservation picks up in the 50s and 60s, someone decides to give these poor engines back their proper names. Visionary class indeed. (And there had better be a preversation movement, what else am I suppoused to do on a weekened, apart from work)

Still, as long as they prevent this being built, I am happy.

John Maclean

Nice update. Maclean seems to have become a sort of George Washington figure for the Union of Britain. Its clear by the time he dies that Federalism is working as well as anyone hoped but nobody seems ready to take the implications of that, yet. This doesn't surprise me (after all, Stalin didn't really take full power until the early 1930s).

The Congress of 1931

The cracks are defenitely appearing but radicalism has at least been temporarily beaten back. The flag of the Union of Britain is quite nice but the only true British flag is the Union jack.

How did Federationism work?

Another interesting update. Again it is clear that Britain is not a Stalinist state. From what I gather, the Federationists seem like the NEP in Russia. This is probably the one big problem I have with this update; it is too similar to being an analogue of OTL. Still, I think Harry Turtledove could learn some things from you.

It is also interesting to hear about the daily life of the British public and the strange little incidents (such as an eleven year old voting) that make British history so interesting.

Too little, Too Late?

This very much a bridging the gap update; Maximism isn't ready to take power but the problems of Federationism continue to mount.

The idea of Clement Attlee being a Maximist is very interesting and actually fits his personality quite well (although I suspect he is a moderate, not a hardliner like Mosley).

Volume II

Ninteen Thirty-Six

A great way to kick off the new volume. The Maximists have taken Britain by storm (not surprising really) but have not seized total power, Horner has some influence and there is always Withrington to fall back on.

Reform and Reaction

A bit boring but still has some tidbits. Britain is modernizing and it looks like the Germans are going to have the mother of all fights on their hands. It is hinted in this update that the Second Great War will not be as short as I feared though; (the blockade comment got that through). BTW, what sort of doctrine does the British army use; is it a form of blitzkrieg? (Or Guerre éclair, as the French probably invented it).

The Second American Civil War

I'll be honest, I was very scared about this update. I was worried this was going to turn into a massive Syndicalist-wank.

Luckily, you surprised and the situation is actually set to be very interesting. The only change I would have made is either have the AUS get New Mexico and Arizona or have Texas survive as an independent entity. The alliance between the AUS and CSA made this update feel like it actually could happen and its nice to see that the old American values of freedom and democracy have not been forsaken by the successor states. Even so, the USA is dead and from it has come five new nations (New England, Hawaii, PSA, AUS, CSA). The North American continent has had its obligatory balkanization.

Just one question, how authoritarian is the AUS really? Since this was a) someone from the CSA and b) Noam Chomsky (the only person I would trust less is Howard Zinn), I'm not sure how much of it I believe (or how much of it is true, but only tells part of the story).

Britain and the Catholic Wars

This update had by far the most serious setback for the Internationale so far; the loss of Spain to the Carlists. However the Carlists seem more like OTL Franco than anything else so hopefully they will stay neutral.

This again shows some of the dsytopian elements of the Union of Britain; Mosley is becoming more like a dictator than ever and this is worrying me. Your writing as always is excellent.

I fear that Ireland is going to be turned into the Poland of this war (eg, the first target of British/German aggression)

Breaking Point

Finally! After four months!

After two updates of foreign news, its nice to get back to Britain. The archieture is shocking (but this is communism, what do you expect?) and daily life has clearly undergone a major change. I fear for the future of Horner and the remaining Federationists.

The cliff-hanger ending was terrifying. Britain is about to enter a dark time.

A Very British Emergency

Mosley seems to have calmed down a bit in this update and showed some great leadership; I actually admire the man for his actions in TL.

It would have been nice to see some actually war, but I suppose we will get plenty of that in the next Volume.

Tensions appear to be rising in Africa and on the continent, so presumably France is going to join the fight at some point.

General Comments:

* Not the unbelievable Syndicalist-wank I feared it was going to be a while back. The Syndies, although good and full of energy, are not invincible; as the USA and Spain have proven.

* So far axe-grinding has been kept to a minimum.

* It is far more realistic and detailed than the Kaiserreich world is in the game.

* You've spaced the changes in governments out; it seems incredible that so many would fall in such a short time (mostly in 1936/37). On the other hand, there was the Berlin Stock Market Crash, so maybe that was the reason they collapse so quickly in the game.

What Next?

* War between the Union of Britain and the Entente is obviously about to break out. This will cause major disruption to transatlantic trade. Who will ultimately win this depends mostly on whether the Germans disrupt Britain's production enough through aerial bombing; on its own Canada cannot produce more ships than the British.

* I doubt the peace on the continent will last past the end of 1941; France and Germany are grappling in Morroco (how ironic, the Syndicalists are fighting with the Imperialists over colonies) and tensions are rising in the Adriatic between Austria and Italy.

* On their own however, I don't think the western Syndicalists will defeat the Germans, they don't have the industrial capacity or the manpower. I do however think it is likely that Russia will attack Germany and their allies. Although the previous chapter mentioned fears of Russian intervention on the Entente side; I think it is exactly that, fears. Between helping their supremely unhelpful allies and taking the chance to maul Germany to death, I think Wrangel will take the mauling option.

* I think it is unlikely that the North American states (apart from Canada and New England) will enter the main war, although there could be a half-hearted grapple between the PSA and Japan over Hawaii. The CSA and AUS will almost certainly trade with their ideological partners and threaten to wipe out anyone who gets in their way.

* Japan is still an unknown, although maybe the international interludes will answer that.

BTW, will the Second Great War be one volume or will their be multiple ones (for each year, or something like that)

I just realized that I implied I admired Oswald Mosley for his actions in OTL; I do not. I admired him for his actions in this update.

Last edited:

I can't help but to shiver when the Police-state side of the UoB rises to the surface....

Same here, but then again I am hardly surprised. There are loads of precedents from OTL that teach us that Uthopian states frequently follow this route.

Same here, but then again I am hardly surprised. There are loads of precedents from OTL that teach us that Uthopian states frequently follow this route.

And Marxism is utopianism embodied. Pity that Marx and his successors totally rejected any form of checks and balances that could have prevented it as 'a capitalist tool for oppression'. I hope that the Union of Britain learns well from Mosley and when Maximism falls, it puts in place the appparatus needed for democracy to flourish.

Iceland? Food prices?

Doesn't everyone catch their own fish?

Or angry 'proletariat' wanting free fish?

Doesn't everyone catch their own fish?

Or angry 'proletariat' wanting free fish?

I'm looking forward to seeing how well the Union copes with a prolonged war- there's obviously going to be a nasty naval conflict ahead but I rather doubt that either side has anything like the capability to attack the enemy on home turf for now at least. And of course neither side will be able to even contemplate the concept of peace talks for a good few years so there's not going to be any easy way out.

nom nom nom, delicious aar...

Next chapter please!

Give him time, its only been two days.

I am Commander Talt and this is my favourite AAR on Paradox Forums (the prize for guessing where that came from: nothing)

Give him time, its only been two days.

I know, I know, but I can't control myself, such is the quality!