General Frederick Funston had been promoted from Major General to Lieutenant General, both as a reward for the safe landing of the American Expeditionary Forces in Europe, and as a sign of Roosevelt’s confidence in him and in the coming American offensive. Funston thus became the first American officer to hold that rank since the closing days of the Civil War and only the second man since George Washington.

The mood at HAEFE (Headquarters of the American Expeditionary Forces in Europe) that spring was jubilant. The passive posture of the German army on the North Sea front seemed to augur well for American chances, and the long-hoped-for spring offensive, named ‘Cobalt’ and aimed squarely at the enemy capital city of Berlin, was thought likely to bring the War to an end. Such lofty goals were perhaps needed, for the French and Russian armies were exhausted – fought out – and it was feared in Washington that one or both allied powers might beg a peace from Germany if the pressure on them could not be relieved.

As a part of the preparations for ‘Cobalt’ the American headquarters was moved from Bremerhaven to the little town of Rotenburg, a picturesque, storybook village of narrow streets and half-timbered medieval houses. The move brought with it a longer than anticipated disruption in communications, taking the headquarters and staff out of easy contact just as von Moltke began to spring his own series of offensives. These thrusts, aimed at Kleves, Nienburg and finally Munster, wreaked havoc on American expectations and plans. An enemy considered ‘spent’ had summoned up twenty-five divisions, moved them quietly into position and then unleashed them on a drive intended to push the American army into the sea.

Rapid reinforcement by Major General Kolgrim Willoch helped the battered American lines to hold at Kleves and then to roll back the German assault. His counter-attack to the south was boldly prosecuted, and while not intended to permanently expand the American perimeter was quite successful in disrupting the movement of German troops and supplies. In the center, American Seventh Army commander General Robert Carmody waited not for approval from headquarters but on his own initiative ordered up the few reserves not already committed. At Headquarters, General Funston and his staff deliberated for three long days while German pressure at Nienburg and Munster grew and grew. Finally accepting that there was no solution possible with available resources, Funston ordered General Leonard Wood’s First Army to halt its advance at Wittenberge. Wood took nearly half of his men west, moving some on captured rail-lines and even commandeering civilian motorcars for transport. His men arrived just in time, blunting the German thrust at Nienburg and relieving the exhausted divisions south of Munster just before the American lines completely collapsed.

None at the Imperial General Staff had thought that the Americans could redeploy so swiftly, or believed that Funston would take action so rapidly or decisively. In truth, much of the credit for halting the German summer drives seems to properly belong to Funston’s subordinates. Willoch fought a masterful defensive action while Carmody held his troops together against overwhelming odds at Munster. By preventing General von Schlieffen from crossing the Dortmund-Ems Canal in force, Carmody likely saved the central part of the American front from collapse – a reverse that would have brought the entire American Expeditionary Force to the brink of ruin. General Wood and his staff must also be honored for making the rapid retrograde movement in time to stave off catastrophe. Moving hundreds of thousands of men with all their equipment, while keeping them fed, armed and supplied, is extraordinarily difficult at the best of times. But to reverse the course of half of that river of men while keeping the remainder un-entangled, and then to rapidly march them across a foreign country-side using unfamiliar and unscouted roads, was a triumph of staffwork. It was also a tribute to the one outstanding characteristic of the American fighting man: a positive genius for initiative and improvisation, a willingness and ability to adapt unorthodox methods and means to get the job done. Had Willoch faltered, or Carmody retreated, or Wood hesitated in the slightest, it is perhaps an understatement to say that the consequences would have been grave indeed.

Once the German offensives were seen to be failing, General Funston called a meeting of all of his high-level commanders to consider what the Expeditionary Force might still do with the remainder of the campaigning season. A majority were in favor of resuming the interrupted ‘Cobalt’ movement on Berlin, despite the enemy having been given more than a month to prepare to resist. It was felt that a strong reserve should be maintained behind the perimeter in the west, making use of the excellent road network north of Munster to counter any further German offensives. A number of officers, including General Willoch, argued for a series of short, sharp blows intended to overwhelm thinly defended sections of the German line. The mood at Headquarters had shifted in dramatic fashion, however. Gone was the sunny optimism of spring, replaced by a sober – even shocked – apprehension at how close the entire army had come to unrecoverable disaster. The German thrusts had been beaten back, but the casualties sustained were horrific. Divisions were blasted down to regimental size, brigades reduced to shadows, whole regiments wiped out. Lost equipment, supplies and munitions could be replaced, and swiftly were made good. But bringing the AEF even partially back to strength had drained the pools of available manpower, and much time would be required to enlarge recruitment and expand the training camps.

Under the circumstances a chastened Funston sided against General Willoch and with General Wood. The Army, he felt, retained enough strength for one hard push, which should logically be directed at an objective whose occupation would force the Germans to fight at a disadvantage. The question of limited offensives could only be reopened after the Army was fully brought back to fighting strength and the new recruits trained to a combat standard. This decision was reached only after much debate and with a thorough discussion of the latest intelligence on enemy deployments – shocking news that seemed to indicate that the German Army, far from being a rolling juggernaut, was itself all but exhausted. It was, said General Wood, “In the way of being a Civil War headline: Good news if true.”

From the west, General Castelnau sent a deputy to report on the new French offensives in the Champaigne, limited thrusts intended to flow around German forces rather than break them down, but still very welcome. Russia sent a quartet of officers to confer with the Americans, an effort that Colonel Simon Burke, Funston’s Chief of Staff, said consisted, “in the main of pleas for additional munitions, rations and if possible troops to be sent East at the earliest possible moment, delivered between demands for more vodka.”

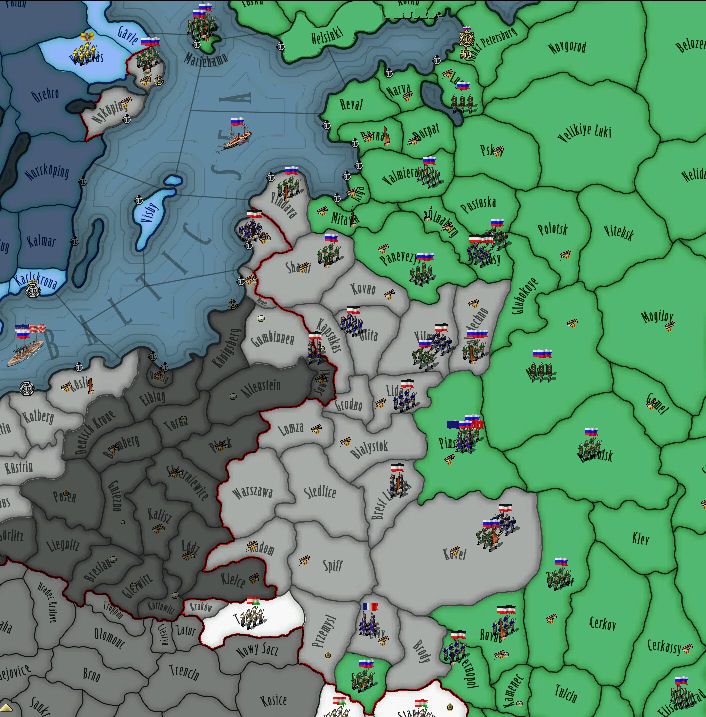

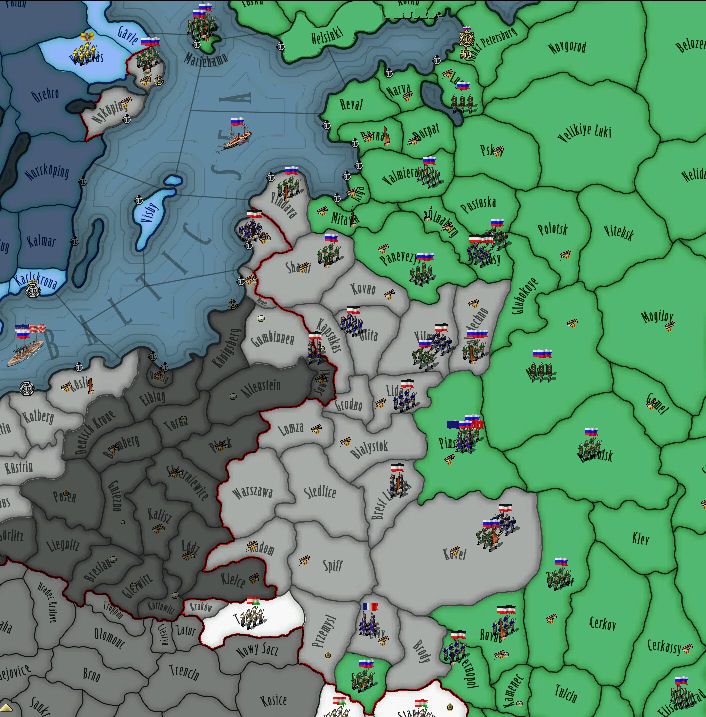

The Eastern Front at the end of July, 1905

And so the national armies would continue, each fighting its own separate war with no co-ordination or combination of effort. But if the intelligence could be trusted, the German Army was in much worse condition than anyone had dared hope. A year of heedless, headlong assaults had brought France and Russia both to the brink of ruin – and in the process might have also bled the Germans white. Now it only remained to be seen if the French and Russians could recover at least some ground before winter once again brought offensive operations to a halt. If Berlin could be taken, if Italy could continue its push on Venice, if Germany could be kept off-balance, if the American public could bear up under the shock of combat losses the like of which they had never seen – if some or all of these could come to pass then it was possible – just possible – that the tide might begin to turn.

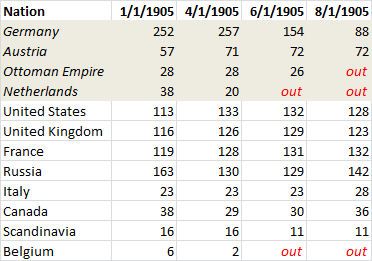

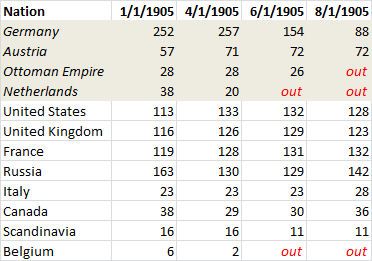

An estimate of the number of infantry divisions available to the combatant nations as of the dates shown, prepared by American Army Intelligence. All figures should be treated as approximate. Note that the United States, Great Britain, the Netherlands, France, Russia and Canada all have large numbers of troops deployed in other theaters.

The mood at HAEFE (Headquarters of the American Expeditionary Forces in Europe) that spring was jubilant. The passive posture of the German army on the North Sea front seemed to augur well for American chances, and the long-hoped-for spring offensive, named ‘Cobalt’ and aimed squarely at the enemy capital city of Berlin, was thought likely to bring the War to an end. Such lofty goals were perhaps needed, for the French and Russian armies were exhausted – fought out – and it was feared in Washington that one or both allied powers might beg a peace from Germany if the pressure on them could not be relieved.

As a part of the preparations for ‘Cobalt’ the American headquarters was moved from Bremerhaven to the little town of Rotenburg, a picturesque, storybook village of narrow streets and half-timbered medieval houses. The move brought with it a longer than anticipated disruption in communications, taking the headquarters and staff out of easy contact just as von Moltke began to spring his own series of offensives. These thrusts, aimed at Kleves, Nienburg and finally Munster, wreaked havoc on American expectations and plans. An enemy considered ‘spent’ had summoned up twenty-five divisions, moved them quietly into position and then unleashed them on a drive intended to push the American army into the sea.

Rapid reinforcement by Major General Kolgrim Willoch helped the battered American lines to hold at Kleves and then to roll back the German assault. His counter-attack to the south was boldly prosecuted, and while not intended to permanently expand the American perimeter was quite successful in disrupting the movement of German troops and supplies. In the center, American Seventh Army commander General Robert Carmody waited not for approval from headquarters but on his own initiative ordered up the few reserves not already committed. At Headquarters, General Funston and his staff deliberated for three long days while German pressure at Nienburg and Munster grew and grew. Finally accepting that there was no solution possible with available resources, Funston ordered General Leonard Wood’s First Army to halt its advance at Wittenberge. Wood took nearly half of his men west, moving some on captured rail-lines and even commandeering civilian motorcars for transport. His men arrived just in time, blunting the German thrust at Nienburg and relieving the exhausted divisions south of Munster just before the American lines completely collapsed.

None at the Imperial General Staff had thought that the Americans could redeploy so swiftly, or believed that Funston would take action so rapidly or decisively. In truth, much of the credit for halting the German summer drives seems to properly belong to Funston’s subordinates. Willoch fought a masterful defensive action while Carmody held his troops together against overwhelming odds at Munster. By preventing General von Schlieffen from crossing the Dortmund-Ems Canal in force, Carmody likely saved the central part of the American front from collapse – a reverse that would have brought the entire American Expeditionary Force to the brink of ruin. General Wood and his staff must also be honored for making the rapid retrograde movement in time to stave off catastrophe. Moving hundreds of thousands of men with all their equipment, while keeping them fed, armed and supplied, is extraordinarily difficult at the best of times. But to reverse the course of half of that river of men while keeping the remainder un-entangled, and then to rapidly march them across a foreign country-side using unfamiliar and unscouted roads, was a triumph of staffwork. It was also a tribute to the one outstanding characteristic of the American fighting man: a positive genius for initiative and improvisation, a willingness and ability to adapt unorthodox methods and means to get the job done. Had Willoch faltered, or Carmody retreated, or Wood hesitated in the slightest, it is perhaps an understatement to say that the consequences would have been grave indeed.

Once the German offensives were seen to be failing, General Funston called a meeting of all of his high-level commanders to consider what the Expeditionary Force might still do with the remainder of the campaigning season. A majority were in favor of resuming the interrupted ‘Cobalt’ movement on Berlin, despite the enemy having been given more than a month to prepare to resist. It was felt that a strong reserve should be maintained behind the perimeter in the west, making use of the excellent road network north of Munster to counter any further German offensives. A number of officers, including General Willoch, argued for a series of short, sharp blows intended to overwhelm thinly defended sections of the German line. The mood at Headquarters had shifted in dramatic fashion, however. Gone was the sunny optimism of spring, replaced by a sober – even shocked – apprehension at how close the entire army had come to unrecoverable disaster. The German thrusts had been beaten back, but the casualties sustained were horrific. Divisions were blasted down to regimental size, brigades reduced to shadows, whole regiments wiped out. Lost equipment, supplies and munitions could be replaced, and swiftly were made good. But bringing the AEF even partially back to strength had drained the pools of available manpower, and much time would be required to enlarge recruitment and expand the training camps.

Under the circumstances a chastened Funston sided against General Willoch and with General Wood. The Army, he felt, retained enough strength for one hard push, which should logically be directed at an objective whose occupation would force the Germans to fight at a disadvantage. The question of limited offensives could only be reopened after the Army was fully brought back to fighting strength and the new recruits trained to a combat standard. This decision was reached only after much debate and with a thorough discussion of the latest intelligence on enemy deployments – shocking news that seemed to indicate that the German Army, far from being a rolling juggernaut, was itself all but exhausted. It was, said General Wood, “In the way of being a Civil War headline: Good news if true.”

From the west, General Castelnau sent a deputy to report on the new French offensives in the Champaigne, limited thrusts intended to flow around German forces rather than break them down, but still very welcome. Russia sent a quartet of officers to confer with the Americans, an effort that Colonel Simon Burke, Funston’s Chief of Staff, said consisted, “in the main of pleas for additional munitions, rations and if possible troops to be sent East at the earliest possible moment, delivered between demands for more vodka.”

The Eastern Front at the end of July, 1905

And so the national armies would continue, each fighting its own separate war with no co-ordination or combination of effort. But if the intelligence could be trusted, the German Army was in much worse condition than anyone had dared hope. A year of heedless, headlong assaults had brought France and Russia both to the brink of ruin – and in the process might have also bled the Germans white. Now it only remained to be seen if the French and Russians could recover at least some ground before winter once again brought offensive operations to a halt. If Berlin could be taken, if Italy could continue its push on Venice, if Germany could be kept off-balance, if the American public could bear up under the shock of combat losses the like of which they had never seen – if some or all of these could come to pass then it was possible – just possible – that the tide might begin to turn.

An estimate of the number of infantry divisions available to the combatant nations as of the dates shown, prepared by American Army Intelligence. All figures should be treated as approximate. Note that the United States, Great Britain, the Netherlands, France, Russia and Canada all have large numbers of troops deployed in other theaters.