Chapter One; Prologue

The Turkocracy

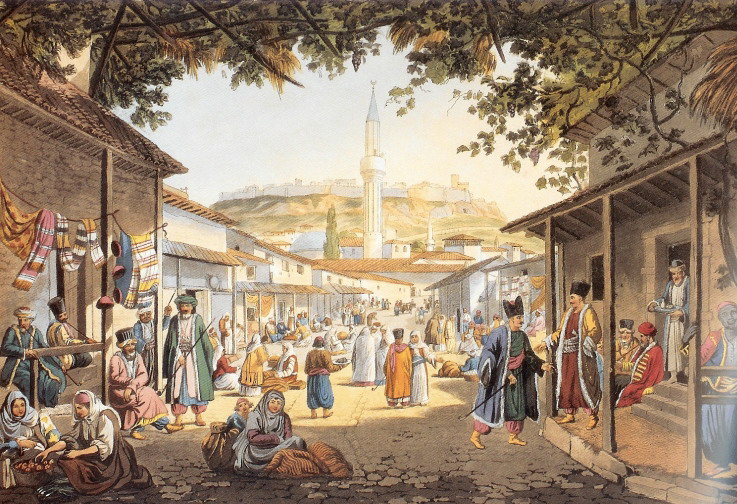

The bazaar of Athens during Ottoman rule

With the fall of Constantinople in 1453 the Byzantine Empire, or the Empire of the Greeks, ceased to exist. This ended the independence of the Greeks, who by then had enjoyed more than a millennium of independence as the Eastern continuation of the Roman Empire. After its failure due to civil wars and corruption amongst her noblemen it was replaced by the Ottoman Empire, which in the century prior was able to conquer the former Greek lands of Anatolia and most of Greece until it blew open the famed walls of Constantinople and (allegedly) killed the last emperor of the Greeks. What followed was nearly four centuries of foreign domination over Greece.

While the rulers and system of governance of Greece was changed from a bureaucratic Greek Orthodox empire to a more feudal Islamic Turkish sultanate, little effectively changed for the Greeks. During the first century the system of peasantry (which was more liberal than the equivalent in Europe) remained nearly unchanged and the new rulers were effectively still the old Greek aristocrats, albeit with new titles and laws. Over time however more and more restrictions and taxes, such as the jizya tax and the enslavement of Greek children for military or more carnal purposes, were put on the Greek population and both Greek peasants from the countryside and many urban civilians fled for the mountainous areas of Greece, which kept more independence from the autocratic Ottomans and were often in revolt against Turkish armies and tax collectors. Many of these places ended up under de facto rule of bandits, also known as klephts.

While the Greeks endured many hardships, they also profited from the Ottoman Empire. As a large and (from a European perspective) educated and civilised population of the empire, the Ottomans gave the Greeks several privileges over other ethnicities in the empire (with the exception of the Turks themselves, of course). Many towns and areas of Greece were granted some form of self-governance while the Greek Orthodox Church under the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople (the chief religious head of the Greeks) was allowed to manage the religious lives of all Eastern Orthodox peoples within the Ottoman Empire, which gave the Greeks a position of leadership amongst other secondary ethnicities within the empire.

The Greeks also dominated in trade and the administration of the empire, the latter surviving until the last few years of the Ottoman regime. This created a large class of wealthy and educated Greek merchants and bureaucrats in the cities while in the rural areas of Greece a new class of Greek notables known as kodjabashis became the elite replacing the declining Ottoman feudal system as they were often in charge of the klephts. While these groups benefitted the most from the Ottoman Empire, they were also the main source of trouble for the Ottomans in the form of Greek nationalism.

The Road to Independence

The Septinsular Republic, arguably the direct predecessor of the modern Greek state

Like Western Europe Greece also experienced the ideas of the Enlightenment. The ideals of liberalism were often passed through to Greek merchants and their families from European merchants and many Greek communities which existed outside of Greece, some of which already established by intellectuals fleeing the beginning of Ottoman rule after the fall of Constantinople. This established the Greek Enlightenment which ran parallel to the Enlightenment in France, the Dutch Republic and the newly created United States of America. With liberalism came the ideas of nationalism, and the Greek elite started to formulate their desire to form a Western-style democratic and modern Greek nation-state to replace the autocratic and oppressive rule of the Turks. Many of these early nationalists gained support from the Enlightened Empress of Russia, Catherine the Great, and from agents from both her and her government. They desired to launch a revolution in Greece to distract the Ottomans so that they could conquer part of the Ottoman Empire. However, this revolution never happened.

Instead of a push given by the Ottomans, the Greeks got their first taste of independence from the French under the general later Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte. After his war in Italy and the annexation of the Republic of Venice in 1797 the French also gained control over the Greek-speaking Ionian Islands, which were given self-rule as the Septinsular Republic, the first self-ruling Greek state after several centuries of foreign domination. Amongst its officials was a Greek nobleman known as Count Ioannis Antonios Kapodistrias, better known as John Capodistrias, the future first democratically elected leader of an independent Greece and seen by many as its founder.

While the French Empire collapsed and with it the short-lived Septinsular Republic, the Greeks now had an educated bureaucratic, mercantile and military elite in favour of independence, a population supporting them and officials from the Ionian Islands with experience of governing a modern country. The Greeks were now ready to create a nation for their own.

The War of Greek Independence

Emblem of the revolutionary Filiki Eteria

In 1814 the Filiki Eteria, or ‘Society of Friends’, was founded by three Greeks (Nikolaos Skoufas, Emmanuil Xanthos and Athanasios Tsakalow) in Odessa as a secret organisation planning the overthrow of Ottoman rule in Greece. Over the next few years it recruited Greeks from diasporas outside of Greece such as in the Danubian Principalities aswell as members within Greece, and many prominent such as Greek politicians, Russian consuls and Greek Ottoman officials. After much preparation they finally found the right time when the Ottomans were busy fighting the recently declared outlaw (and sometimes considered pro-Greek) Ali Pasha of Ioannina while the Great Powers were involved in putting down revolts in Italy and Spain, which would distract them from intervening early in the soon to happen Greek War of Independence.

The revolution did not start in Greece itself, but in the Danubian Principalities. A small army of Greeks proclaimed an uprising against the Ottoman Empire, implying support from ‘a Great Power’, and was joined by many sympathetic Romanians. Soon after several rebellions in southern Greece (including the entire Peloponnese) surprised the Ottomans, who subsequently lost almost all control over the area after garrisons were overrun.

After the Greeks took over control over Southern Greece, several mass killings against Muslims happened, which resulted in the deaths of up to 40% of Muslim communities in the Peloponnese and the fleeing of the remainder of the population to Ottoman-friendly lands. This provoked a response from Ottoman armies, who started to commit atrocities in Greek areas still under Ottoman rule such as the island of Chios, which shocked a large part of the Western world. Many Orthodox priests including the Ecumenical Patriarch Gregory V.

While the revolution angered many of the conservative leaders, who only recently were able to put down revolts in other parts of Europe to desperately maintain the newly-created Concert of Europe system of counterrevolution, much of Europe supported and celebrated this liberal revolution against a conservative and autocratic empire ruled by Muslims.

Many volunteers from European countries as well as Greeks living outside of Greece travelled to Greek-held lands to join in the revolution. The most famous of these volunteers was Lord Byron, a romantic and a both famous and infamous poet. He captivated the hearts of many European citizens with his poems describing the struggles of the long-suffering Greeks against the despotic Ottoman Empire.

The war remained a stalemate between the Greeks and the Ottomans, until the Ottoman leadership sent the Albanian Ali Pasha, governor of territories such as Egypt, to Greece with an army to quell the rebellion. The many atrocities committed by his forces however angered the three European powers France, the United Kingdom and Russia, the latter of which already starting to become more aligned with the Greeks after the Ottomans executed Orthodox priests such as the Ecumenical Patriarch. The death of Lord Byron during the struggle with Ali Pasha’s forces also caused sadness and further anger amongst the citizenry of European countries.

In October 1827 British, Russian and French naval officers were allowed to intervene in the war by their governments, which culminated in the destruction of the Ottoman navy in the Battle of Navarino. After this battle and subsequent military interventions by Russia and France the Great Powers and the Ottoman Empire started talks to officially establish an independent Greek state in March 1829, which culminated with the official recognition of a Greek state in 1832.

The Bavarocracy

The arrival of the Bavarian Army in Greece in 1833

While they won the war, Greece as a country was still in turmoil. Already in 1824 the Greek Republic (also known as the Hellenic Republic) was plunged into two civil wars, and a French intervention in Morea was later needed to re-establish a Greek government. While a unified government was finally achieved under John Capodistrias as Governor of the Hellenic State, many political intrigues within its feeble government culminating in the assassination of Capodistrias by his rivals from the Mavromichalis family plunged the country into chaos again.

At the behest of Russia, which feared the instability caused by democracy in its potential new Orthodox ally in the south, the Great Powers decided that Greece was to become a monarchy under a prince from one of the German principalities. While Leopold of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha (the later King Leopold of Belgium) was at first considered to be the best candidate to become King of Greece, it was decided that the very young Prince Otto von Wittelsbach, second son to King Ludwig of Bavaria, would become king of the newly formed Kingdom of Greece. One of the reasons Otto was chosen as king was because through his ancestor Duke John II he was an official descendant of the Byzantine Komnenos and Laskaris dynasties.

An agreement was drafted in which it was decided that King Otto would be titled ‘King of Greece’ as opposed to ‘King of the Hellenes’ to avoid a possible future claim to kingship over all the Greeks, as well as an agreement that declared that under no circumstances would the crowns of Greece and Bavaria be united. As King Otto was still only a minor, a regency council under the leadership of the liberal Bavarian nobleman Josef Ludwig von Armansberg was formed, which would also become the government of Greece between 1832 to 1835.

At the time when the Kingdom of Greece was formed it was already found to be in a state of near anarchy as many of the klephts started to return to their normal jobs as brigands while the bureaucracy was non-existent. Bureaucrats from mainly Bavaria and other German principalities, with a few aides sent by the Great Power, started to pour into Greece to form a mostly German-speaking rudimentary government and administration while German officers would replace some of the native officers and compete with the remaining ones within the Greek army, which was by then the only stabilizing force within the country. Several heroes of the Greek revolution such as the generals Kolokotronis and Makriyiannis were imprisoned for treason because of their opposition to the Bavarian regency, although they were later pardoned and restored to their former positions in the army.

King Otto travelled to Greece in 1833 on the British ship HMS Madagascar, and while he could not yet speak Greek he immediately started to adopt Greek customs when he arrived in the country and even Hellenized his name to King Othon. He was accompanied by the Bavarian Auxiliary Corps, which while supposedly remaining an independent unit was quickly integrated into the Greek army and became the backbone of Otto’s early reign as well as a source of many officials for the later government.

The Regency continued until Otto’s birthday on the 1st of June 1835. The Bavarian (or just generally German) government remained unpopular, as it was dominated by foreigners who tried to implement the rigid German hierarchical structure while favouring foreign officials over native Greeks. The Bavarocracy, as it came to be called, was dominated by Roman-Catholic Christians who tried to actively fight the Orthodox church from Constantinople, which caused many priests and monks to live in poverty while the Greek Orthodox Church was severed from Constantinople and many of the monasteries were closed. While some elements of Greece tried to form a Greek parliament this process was halted by King Otto, who desired to be an absolute monarch aided by his Bavarian nobles from the former Regency council, with whom (especially with Von Armansperg) he started to clash. In the final months of 1835 plans were made for King Otto to travel back to Bavaria to marry the gorgeous princess Amalia von Oldenburg, while his former Regent and now Prime Minister Von Armansperg was once again left in charge of the Kingdom of Greece. In this year it was also decided that Athens (which by now declined to a small town of about 400 houses) would become the kingdom's capital city, and plans were already made to transform it into a modern city for a proper Western nation.

And now, on the eve of 1836, will our story start.

"Grateful Hellas" by Theodoros Vryzakis

Author's note:

Whew, this took a while longer than expected!

I was unhappy with the first draft I've made, since I found it a bit too boring as it felt more likely a summary of battles and rebellions. Instead I've written this shorter summary which is mostly meant to give a bit of an introduction to Greek history from 1453 to 1836. I'd encourage everyone who is interested in Greek history from any of these periods to read more about it. I wish I had some better sources on the Bavarocracy, but the only good English source I could find (for now) is the book Politics and Statecraft in the Kingdom of Greece, 1833-1843 by John Anthony Petropulos, but the book is only published by Princeton University, which is demanding a rediculous price for a copy of it. If I'm lucky I'll be able to pull some strings at the University of Leiden to look whether they have a copy of it, since the UvL has one of the most prominent History faculties in this part of Europe.

I've currently alligned the entire text to the centre. If that's too annoying to read then I'll put most of the text back to the left!

Part two of Chapter One will be out tomorrow, since that's way shorter and easier to write.

~Nicolaes