You're too far gone. It's gotten to the point where you want me to write a damn book on stuff you learn in basic history books or an introductory university course. I'm done.

About Stalin's intentions regarding Finland in WW2

- Thread starter FulmenTheFinn

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You're too far gone. It's gotten to the point where you want me to write a damn book on stuff you learn in basic history books or an introductory university course. I'm done.

True historiography has never been tried!

You mean this: "If a tree happens it happens, key is that priority comes in the global scale and countries that influenced on a global scale. The Great Powers were the ones pulling the weight and deciding WW2." ? The Great Powers already have their won focus trees, it seems the devs now work half on the great powers and half on the minor powers in each DLC.Within it is the less "personal" answer, sorry for the ramble

Topics like these are welcomed because Hearts of Iron 4' Dev isn't exactly synonyms with historical accuracies. I don't think they have a historian or something similar, they probably do their own doccumentation, as there are cases where history is simplified for the sake of a smoother gameplay, but this is way beyond that, many things in the game from a historical point of view are just wrong. So a topic like this that regards the history of a minor nation in WWII is more than welcomed, in this case Finland.

The subject of our discussion is whether it's worth making topics like these isn't it?

- You complained about OP making this topic - "my country needs a focus tree, they did amazing things yaddayaddayadda"

- I told you that minors have interestind deeds as well, but they're less popular.

- You said you don't care about minor powers and majors get more attention.

- I told you that personal experience doesn't make for an argument.

- You said that in the middle of your comment there was an impersonal argument.

- I replied to the impersonal argument you made.

For anyone interested, I have made a similar topic but about Romania: https://forum.paradoxplaza.com/forum/index.php?threads/world-war-ii-viewed-from-romanias-perspective.1243453

Well, I think that Paradox's development teams should spend 100% of their time on EACH major and minor country in the world, just to guarantee fairness. After all, every country is a special case, and did amazing things; the only small difference is that the amount of amazing things varies "a bit" from one to the next.You mean this: "If a tree happens it happens, key is that priority comes in the global scale and countries that influenced on a global scale. The Great Powers were the ones pulling the weight and deciding WW2." ? The Great Powers already have their won focus trees, it seems the devs now work half on the great powers and half on the minor powers in each DLC.

Seeing what the developers did for a Hungarian DLC in HOI4, I've got no illusions that there's a historian in any way involved. It's comically bad, and completely contrary to the majority of Hungarian aspirations and objectives at the time, practically akin to allowing Israel a focus tree branch to reconstitute the Third Reich (I hope I didn't give them any ideas for a "Star of David" DLC).

In their very early days, I think Pdox used to do their own research, and also heavily relied on beta testers and forum contributors with backgrounds in history.

These days they see to largely make up stuff that sounds cool to Wehraboos because let's be honest, the games sell well regardless of their supposed historical accuracy.

These days they see to largely make up stuff that sounds cool to Wehraboos because let's be honest, the games sell well regardless of their supposed historical accuracy.

These days they see to largely make up stuff that sounds cool to Wehraboos because let's be honest, the games sell well regardless of their supposed historical accuracy.

It's not just wehraboos. The HOI4 dev team keeps inventing ways for Leon Trotsky to be relevant.

I expressed the official Russian version.

The analogy with the current political situation suggests itself.

Violation of international rights by the West. For example, the invasion of Yugoslavia. And in those days, Hitler's pacification policy was the surrender of Alsace-Lorraine, the Sudetenland and Czechoslovakia.

In response, Russia is taking defensive measures already without looking at international charters. Because the guarantee of our own safety is higher than international standards.

The analogy with the current political situation suggests itself.

Violation of international rights by the West. For example, the invasion of Yugoslavia. And in those days, Hitler's pacification policy was the surrender of Alsace-Lorraine, the Sudetenland and Czechoslovakia.

In response, Russia is taking defensive measures already without looking at international charters. Because the guarantee of our own safety is higher than international standards.

Wow, you really have been drinking the tankie kool-aid. Is there any piece of Soviet propaganda that you can name that you don't believe in?

It seems the answer is "no." See above. It would be funny if it wasn't so sad. To think that he/she actually thinks that stopping ethnic cleansing is a violation of international law is ridiculous.

Last edited:

So it is possible to fight with Russia/USSR. Especially in the 1920s/30s?Very simple, that country was in the midst of a many-faceted civil war, lacked the ability to impose itself on Finland, and Finland was relatively independent during Tasarist rule (the taking away of which was a big reason for the strengthening of the independence movement), so it could extradite itself with the institutional framework of a nation already built.

That said, there was also a civil war within Finland, where the Reds did receive Soviet support.

That the USSR had no industry in 1932 is a laughable claim that deserves derision at best.

Do you believe words of comrade Stalin?

"We are 50-100 years behind the advanced countries. We must run this distance ten years. Either we will do this or they will crush us," Joseph Stalin said at the first All-Union Conference of Workers of Socialist Industry on February 4, 1931.

Do you believe words of comrade Stalin?

No.

"We are 50-100 years behind the advanced countries. We must run this distance ten years. Either we will do this or they will crush us," Joseph Stalin said at the first All-Union Conference of Workers of Socialist Industry on February 4, 1931.

Doesn't mean it's true. Stalin justified all kinds of evil crap with complete bullshit. But go ahead and believe him. Those Estonians are sure out to get the Soviets! Everyone just wants to destroy the Soviets! Pay no attention to the gulags comrade! Sacrifice your rights to the glory of the Union!

No, why? Do you think Stalin is a trustworthy person? I would love to hear why you think something so silly.Do you believe words of comrade Stalin?

I did, I love that game. I have an installation of IL-2 1946 with HSFX and some other mods and a few mostly superficial changes of my own.

So I suppose you will agree wuth my statement that it is very difficult to understand what happens in reality in the sky? At least having some problem with it.

There's a long way from misidentifying a few aircraft and exaggerating a few kills, to claiming to have bombed literally dozens of airfields and destroyed 130 aircraft when the real sum of both is actually 0. Also note that e.g. Novikov and many other Russian sources claim that this is actually what happened, not that it was "merely ordered, but happened in a different way".

I posted reports where pilots and staff were sure about results. I suppose Novikov used reports and own memory about it too. Modern Russian historians started to compare papers from both sides and they mostly agree with Finish statements about results. Due propaganda Finish ones do not ready to analyze Soviet intentions (Ordes/reports an so on). It is more easy for nation to think that USSR bombed civilian cities instead of millitary airfields.

Well the reality of the events has been available to Russians at least since the end of hostilities since 1944, and probably already during the war, but the communist regime in Russia did not allow for the publication of historical facts that put the official state propaganda version of history into question. That only really started to change in the 1980s-90s, but in the past almost 20 years the Russian state under Putin seems to be adopting a more traditional pro-Stalinist propaganda-driven "interpretation" of history..

Partly yor right, but also we were very closed country. Only recent 20-30 years our historians started to use comparing of USSR's and foreighn reports about events. Help to forums like it we are hearing foreighn point of view.

Many generals and other high ranking officers were, but much of the decision-making top was old Tsarist era as well. And anyway Mannerheim himself made the big military decisions during the war. "Dreams of a Greater Finland", whether harbored by certain individuals or not, did not influence decision-making on either political or military level.

Bair Irincheev wrote that Mannerheim did "Miekantuppipäiväkäsky" in 1918 and 1941:

What @Herbert West already said, and also I'd like to note that Lenin armed and incited Finnish Reds into rebellion......

I just wanted to note that it was possible for Finland to resist more huge in territory Russia/USSR. And Finland proved it, isn't it?

P.S. What about names of divisions of 7 Army corps? I want to find it on your map before war...

Last edited:

So you know much more about Soviet industry than I and comrade Stalin.

Let you teach us about it. Can you start from type of Soviet tanks and their quantity in the 1931 (To see how USSR's industry could provide Soviet Army...)

No, why? Do you think Stalin is a trustworthy person? I would love to hear why you think something so silly.

Just try to prove that he was lying here.

I myself do not really adore Stalin. The reason for my antipathy is the transfer by Stalin of Xinjiang to China and the assassination of their leaders.

Stalins popularity is very high among the Russians (this is a paradox - when Yeltsin came to power - Stalin was considered a villain, now he is the actual founder of modern Russia, a symbol of victory in the Great War). The popularity of Stalin is mush higher than Putin, the rule of Stalin is considered the golden age of Russia.

The fact is that every country has national problems. The Russians believe that because of the war in Chechnya, the West may declare war on them. The war in Chechnya can also be characterized as ethnic cleasing.

Or the war in Iraq, with which the USSR had long-term projects. Bush declared war on them over allegedly available nuclear weapons, but in the end, the Americans did not provide evidence of the existence of atomic weapons in Iraq.

About Yugoslavia - Russians lose their reason, logical thinking when they hear about the bombing of Serbia. Because of Serbia, Russia entered the First World War. They considet them brothers. Until 1999, Russians liberals enthusiastically talked about democracy and international standarts. But after this war, i remember the expression on their faces on the screen, they stopped talking about the norms of international law.

Russia felt a particular threat: 1) US withdrawal from the missile defense treaty, 2) NATO expansion to the East. When the Warsaw Pact terminated, it was specifically agreed that NATO should not expand to the East. But the West has broken this promise

Stalins popularity is very high among the Russians (this is a paradox - when Yeltsin came to power - Stalin was considered a villain, now he is the actual founder of modern Russia, a symbol of victory in the Great War). The popularity of Stalin is mush higher than Putin, the rule of Stalin is considered the golden age of Russia.

The fact is that every country has national problems. The Russians believe that because of the war in Chechnya, the West may declare war on them. The war in Chechnya can also be characterized as ethnic cleasing.

Or the war in Iraq, with which the USSR had long-term projects. Bush declared war on them over allegedly available nuclear weapons, but in the end, the Americans did not provide evidence of the existence of atomic weapons in Iraq.

About Yugoslavia - Russians lose their reason, logical thinking when they hear about the bombing of Serbia. Because of Serbia, Russia entered the First World War. They considet them brothers. Until 1999, Russians liberals enthusiastically talked about democracy and international standarts. But after this war, i remember the expression on their faces on the screen, they stopped talking about the norms of international law.

Russia felt a particular threat: 1) US withdrawal from the missile defense treaty, 2) NATO expansion to the East. When the Warsaw Pact terminated, it was specifically agreed that NATO should not expand to the East. But the West has broken this promise

Last edited:

Yes.So it is possible to fight with Russia/USSR. Especially in the 1920s/30s?

Do you believe words of comrade Stalin?

"We are 50-100 years behind the advanced countries. We must run this distance ten years. Either we will do this or they will crush us," Joseph Stalin said at the first All-Union Conference of Workers of Socialist Industry on February 4, 1931.

Here are the proposed plans for the destruction of the USSR, developed by the Western Allies:

1) Operation Unthinkable: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Unthinkable, 1945,

2) "Dropshot" Plan https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/План_«Dropshot» 1947,

3) Operation Pike https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Pike 1940/

Axis countries - of course, the first thing they did was prepare for war against the USSR.

The history of a betrayal / On the 80th anniversary of the armed conflict at about. Hasan

Before the war, the Japanese sent a commando group to Sochi to kill Stalin https://mamlas.livejournal.com/6705769.html

In July - August marks 80 years since the events on Lake Hassan that could change the course of history, draw our country into the Second World War even earlier than the Western powers. In the summer of 1938, the allied Nazi Germany and fascist Italy, militaristic Japan used the clash on the Soviet-Manchu border, which there were many in the 30s, to conduct large-scale "reconnaissance" by forces of the division.

Fighters set the banner of victory on the hill Zaozernaya. 1938

It was important for the Japanese command to find out the degree of defense capability of the Soviet troops in the Far East, and whether the Soviet leadership was going to respond to the expansion of the war in China by Japan not only by political and material support of the Chinese people fighting the aggressors, but also by direct military operations of the regular troops of the Soviet Union.

The author of these lines already told readers of REGNUM news agency about how the armed provocation was conceived and passed. However, there is a plot in this story that was not customary to mention in Soviet times.

This story is about the escape to the Japanese before the Japanese provocation, by the head of the NKVD Directorate for the Far East, the third-level state security commissioner (corresponded in the army with the rank of commander, then lieutenant general) Heinrich Samoilovich Lyushkov. I remember, being a young associate of the Institute of Military History of the USSR Ministry of Defense, I found information about this escape in Japanese literature and invited the editors of the forthcoming edition of the 12-volume History of World War II to somehow illuminate this fact and its consequences. But he was refused and advice not to mention the fact of betrayal of such a high-ranking security officer in the forthcoming dissertation and publications.

In Japan, there were many publications and articles about the circumstances of the escape and the further fate of the traitor Lyushkov in the postwar period. And in 1978, a Japanese researcher and columnist Yoshiaki Hiyama published a book entitled "Plan of assassination of Stalin. An empirical analysis of the secret design of the Japanese army. ” It tells about the plan to use Lyushkov for the attempted assassination of Japanese agents on the life of the Soviet leader - Joseph Stalin.

Heinrich Lyushkov

Heinrich Lyushkov was born in 1900 in Odessa in the family of a Jewish tailor. After studying at the government primary school, and then at evening general education courses, he worked in the office of automobile supplies.

Under the influence of his older brother, he took part in revolutionary activities. In July 1917 he became a member of the RSDLP (b). In the same year, he joined the Red Guard in Odessa as an ordinary. Since 1918 - in the organs of the Cheka. He was the political instructor of the Shock Separate Brigade of the 14th Army.

After the Civil War, having passed a number of posts, in 1931 he was appointed head of the secret political department of the GPU (State Political Administration) in Ukraine. Then he was sent to Moscow to serve in the central apparatus of the OGPU (United State Political Administration). Lyushkov used the location of the People's Commissar of Internal Affairs of the USSR in 1934-1936, Heinrich Yagoda. He actively participated in high-profile investigations - the “Kremlin case”, the case of the “Trotskyist-Zinoviev center”. After which he was appointed head of the NKVD in the Azov-Black Sea Territory, which subsequently played a significant role in the Japanese operation to physically eliminate the Soviet leader. In early June 1937, for the zeal shown in the “purges”, he was awarded the Order of V. I. Lenin.

In 1937-1938 - Head of the NKVD Directorate for the Far East. Japan’s full-scale war in China has already begun, the selected Kwantung Army (Army Group), standing on the far eastern border of the USSR, was preparing for a future war against the Soviet Union, provoking border conflicts. In those years, the danger of the USSR becoming involved in a big war came primarily from Japan. Stalin showed increased attention to the situation on the Far Eastern borders of the country. According to some reports, the leader, before sending Lyushkov to the Far East, considered it necessary to briefly instruct him personally by inviting him to a 15-minute audience.

Soldiers of the Kwantung Army, 1938

Arriving in Khabarovsk, the new head of the NKVD began vigorously “eradicating the enemies” and purging the local UNKVD. He was charged with the creation of a right-wing Trotskyist organization in the internal affairs bodies of the Far East. Lyushkov was the main organizer of the deportation of Koreans from the Far East as potential Japanese spies.

Being an approximate and nominee of Yagoda, Lyushkov was suspected of belonging to a counter-revolutionary organization. Stalin was not informed of suspicions, having decided to interrogate Lyushkov and make sure that he was not involved in the conspiracy. But the question of political distrust of the State Security Commissioner was raised by the commander of the Far Eastern Army, Marshal of the Soviet Union V.K. Blucher.

May 26, 1938 Lyushkov was relieved of the duties of the head of the Far Eastern UNKVD allegedly in connection with the reorganization of the GUGB NKVD and the appointment to the central office. The People's Commissar of Internal Affairs N. I. Yezhov informed him about this in a telegram, where he asked for his attitude to the transfer to Moscow. Lyushkov realized that he would be arrested in Moscow. It was decided to escape and surrender to the Japanese, offering important information and other services for them.

However, according to published archival data, the decision was not spontaneous, but carefully thought out. Lyushkov prepared his escape in advance, two weeks before calling to Moscow, ordering his wife and her daughter to go to one of the European countries, ostensibly for her treatment. The necessary documents for leaving the USSR were prepared by Lyushkov in advance.

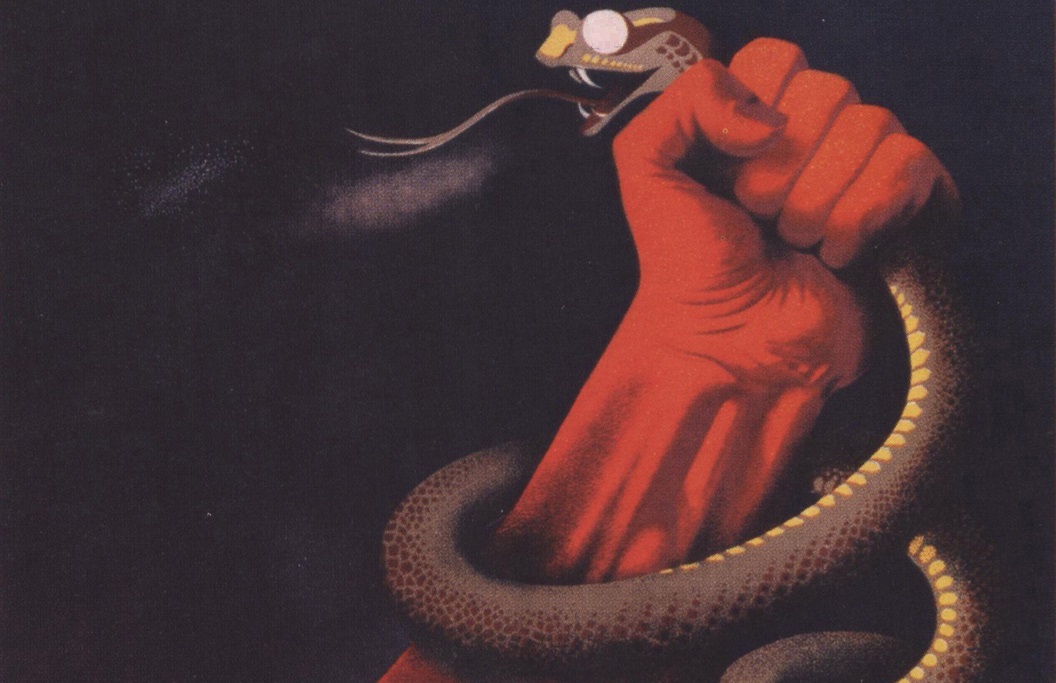

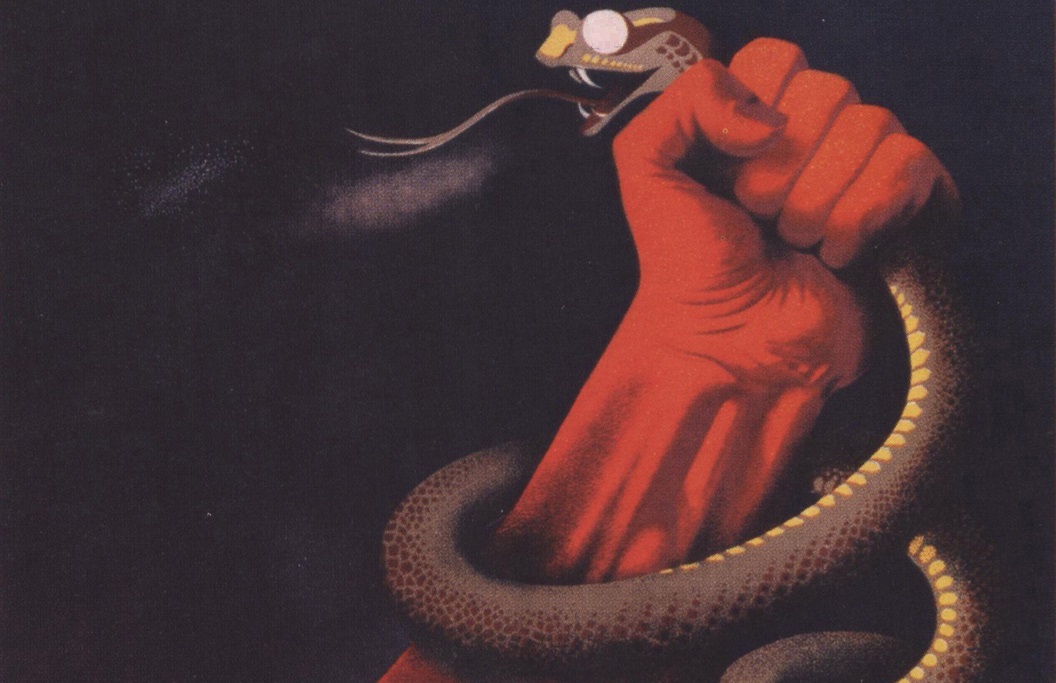

Sergey Igumnov. Eradicate spies and saboteurs! (fragment) 1937

Here is how the circumstances of the flight of the commissar of the NKVD are described:

“On June 9, 1938, Lyushkov notified his deputy of his departure to the border Posyet for a meeting with a particularly important agent. On the night of June 13, he arrived at the location of the 59th border detachment, ostensibly to inspect the posts and the border strip. Lyushkov was dressed in a field uniform at the awards. Having ordered the chief of the outpost to accompany him, he walked on foot to one of the sections of the border. Upon arrival, Lyushkov announced to the attendant that he had a meeting on the “other side” with a particularly important illegal Manchu agent, and since no one should know in person, he would go on alone and the head of the outpost should go half a kilometer towards Soviet territory and wait for the conditional signal. Lyushkov left, and the head of the outpost did as ordered, but, after waiting for him for more than two hours, he raised the alarm. The outpost was shotgun, and more than 100 border guards combed the area until the morning. More than a week, before news came from Japan, Lyushkov was considered missing, namely, that he was kidnapped (killed) by the Japanese. By that time, Lyushkov had crossed the border, and on June 14, 1938, at about 5:30 am near the city of Hunchun, he surrendered to the Manchu border guards and asked for political asylum. After he was transported to Japan and collaborated with the Japanese military. ”

Like many other traitors, Lyushkov tried to explain his betrayal not by selfish, but by political motives. In an interview with the Japanese newspaper Yomiuri Shimbun dated July 13, 1938, he convinced: “Until recently, I committed great crimes against the people, since I actively collaborated with Stalin in pursuing his policy of deception and terrorism. I really am a traitor. But I am a traitor only in relation to Stalin ... These are the immediate reasons for my escape from the USSR, but this is not the end of the matter. There are more important and fundamental reasons that made me act this way.

This is what I am convinced that Leninist principles have ceased to be the basis of party politics. I first felt hesitation since the assassination of Kirov by Nikolaev in late 1934. This case was fatal for the country as well as for the party. I was then in Leningrad. I was not only directly involved in the investigation of Kirov’s murder, but I also took an active part in public trials and executions after the Kirov case ... ”

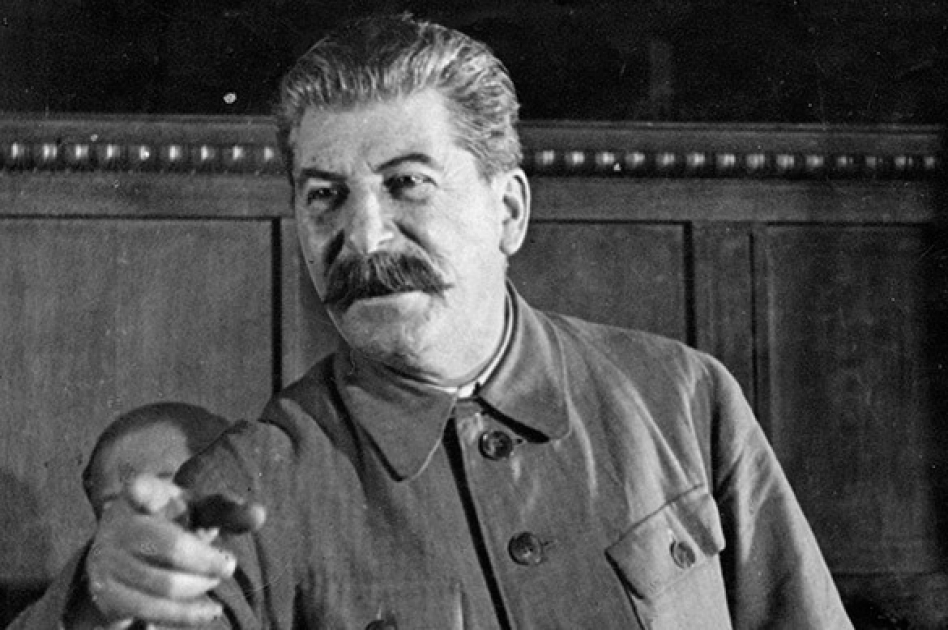

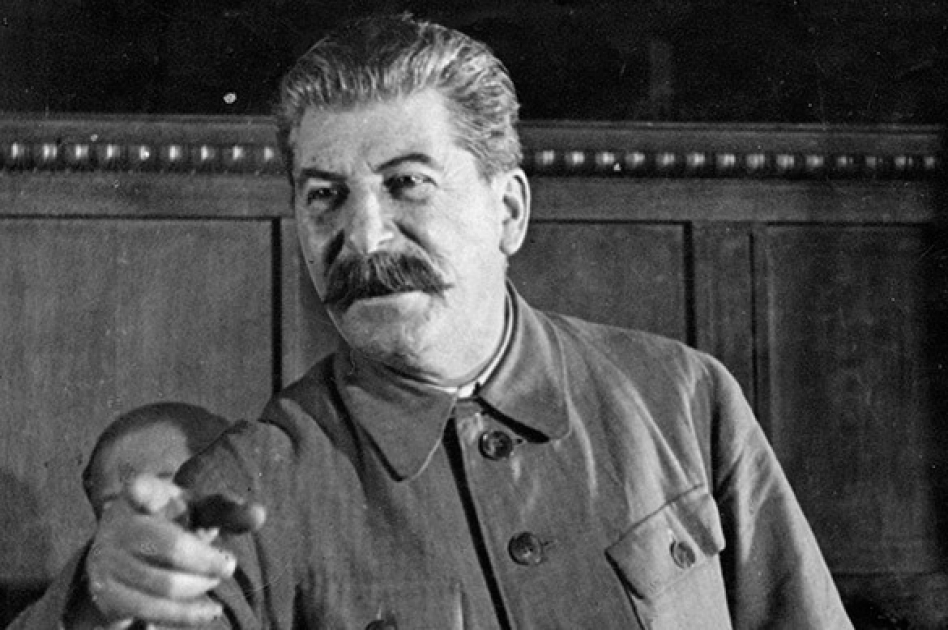

Joseph Stalin

In reality, Lyushkov was an ordinary careerist and traitor, who did great harm to the Soviet state and people, transmitting to the Japanese special services extremely important information about the Soviet armed forces, especially in the Far East, about the deployment of troops, the construction of defensive structures, fortresses and fortifications. The Japanese received detailed, top secret information about the plans for the deployment of Soviet troops not only in the Far East, but also in Siberia, Ukraine, and military radio codes were revealed to them. The defector significantly weakened the USSR intelligence network in neighboring countries, betraying important Soviet agents.

In Japanese sources, the consequences and impact of the information transmitted by Lyushkov on Japanese military plans for the Soviet Union are assessed differently. On the one hand, it is believed that Tokyo decided to check the information transmitted to them about the shortcomings in the defense capabilities of the Soviet troops, which encouraged the Japanese command to expand the incident near Lake Hassan.

On the other hand, there is an opinion that, having learned the true alignment of forces and means of the opposing Japanese and Soviet groups in the Far East, the Japanese command was already planning much greater war with the USSR. It was unexpected for them that, according to Lyushkov, the USSR has a rather significant military superiority over the Japanese in the Far East.

Here's how the former officer of the 5th (Russian) intelligence department of the Japanese General Staff, Koichiro Koizumi, evaluated the information received from Lyushkov:

“The information that Lyushkov reported was extremely valuable for us ... In the information received from Lyushkov, it struck us that the troops that the Soviet Union could concentrate against Japan possessed, as it turned out, overwhelming superiority. At that time, that is, at the end of June 1938, our forces in Korea and Manchuria, which we could use against the Soviet Union, consisted of only 9 divisions ... Based on the information received from Lyushkov, the fifth section of the General Staff concluded that The Soviet Union can use up to 28 infantry divisions against Japan under normal conditions, and if necessary concentrate from 31 to 58 divisions ... The ratio in tanks and aircraft also looked alarming. Against 2000 Soviet aircraft, Japan could only deploy 340 and against 1900 Soviet tanks only 170 ... Before that, we believed that the Soviet and Japanese armed forces in the Far East were related to each other as three to one. However, the actual ratio turned out to be about five or even more to one. This made it virtually impossible to implement the previously drawn up plan of military operations against the USSR ... "

Disguised Soviet T-26 tanks

Such assessments even gave rise to thoughts whether Lyushkov was specifically sent as a defector to the Japanese in order to intimidate them with the might of the Soviet army and force them to abandon plans for an attack on the USSR. Which, of course, is unlikely. Moreover, Lyushkov proposed a plan for the assassination of Stalin and expressed his readiness to take part in the operation to destroy the Soviet leader himself.

In his book, Y. Hiyama reports that Lyushkov offered the Japanese a plan to kill Stalin. They grabbed him willingly. On duty, as head of the NKVD branch in the Azov-Black Sea Territory, Lyushkov was personally responsible for protecting the leader in Sochi. He knew that Stalin was being treated in Matsesta. The location of the building where Stalin took baths, Lyushkov well remembered the order and security system, since he himself developed them. Lyushkov led a sabotage group of Russian emigrants, which the Japanese transferred to the Soviet-Turkish border in 1939. However, a Soviet agent was introduced into the sabotage group and the crossing across the border failed.

Koichiro Koizumi denied Lyushkov’s participation in the operation, saying that "Tokyo refused his candidacy as an executor of a terrorist act against Stalin." Obviously, because he was a fairly well-known figure and would certainly have been recognized. Nevertheless, there is evidence that an attempt was made to transfer the Japanese subversive group across the Soviet-Turkish border.

Red army soldiers go on the attack. Surroundings of lake Hasan. One thousand nine hundred thirty eight

In one of the publications, the British newspaper The News Cronicle wrote about the failure of the terrorist attack on January 29, 1939: “As reported by TASS, on January 25, the Georgian SSR border guard killed three people trying to cross the border from Turkey. These three are Trotskyists, supported by the Nazis. The dead found pistols, hand grenades and detailed maps of the area.

The purpose of the criminal group was the killing of Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin, who was in Sochi. However, the border guards learned in advance about the criminal plan and exterminated the attackers. The People’s Commissar of Foreign Affairs Litvinov strongly protested that Turkey had become the base of anti-Soviet provocations. ”

It was such a statement by TASS, and whether it was about a sabotage operation prepared by Japanese intelligence using Lyushkov’s help, it’s hard to say now. But there is a lot of evidence that a plan for the physical destruction of Stalin on the eve of the war existed in Japanese literature and periodicals.

The Japanese did not hide the fact that shortly before the defeat of Japan, in July 1945, Lyushkov was transferred from Tokyo to the location of the Japanese military mission in Dairen (China) to work in the interests of the Kwantung Army. Japanese sources claim that after the Soviet Union entered the war and Hirohito announced that he would surrender, on August 19, 1945, Lyushkov was summoned to the head of the Dairen military mission, Yutaka Takeoka, who suggested he commit suicide in order to exclude disclosure if he was captured if he knew about Japanese intelligence. Since Lyushkov refused to shoot, Takeoka himself shot him and his body was secretly cremated.

The ceremony of signing the Act of Surrender of Japan. Representative of the USSR General K.N. Derevyanko signs the act. September 2, 1945

There is another version that Lyushkov was allegedly brought to Dairen to extradite the USSR in exchange for the captured son of the former Prime Minister, Prince Fumimaro Konoe. Upon learning of the impending extradition, he made an attempt to escape, but was strangled by Japanese officers.

Be that as it may, a fair punishment would have overtaken the traitor in any case, since back in 1939 Lyushkov was sentenced in absentia by the Soviet court to death.

Fighters set the banner of victory on the hill Zaozernaya. 1938

It was important for the Japanese command to find out the degree of defense capability of the Soviet troops in the Far East, and whether the Soviet leadership was going to respond to the expansion of the war in China by Japan not only by political and material support of the Chinese people fighting the aggressors, but also by direct military operations of the regular troops of the Soviet Union.

The author of these lines already told readers of REGNUM news agency about how the armed provocation was conceived and passed. However, there is a plot in this story that was not customary to mention in Soviet times.

This story is about the escape to the Japanese before the Japanese provocation, by the head of the NKVD Directorate for the Far East, the third-level state security commissioner (corresponded in the army with the rank of commander, then lieutenant general) Heinrich Samoilovich Lyushkov. I remember, being a young associate of the Institute of Military History of the USSR Ministry of Defense, I found information about this escape in Japanese literature and invited the editors of the forthcoming edition of the 12-volume History of World War II to somehow illuminate this fact and its consequences. But he was refused and advice not to mention the fact of betrayal of such a high-ranking security officer in the forthcoming dissertation and publications.

In Japan, there were many publications and articles about the circumstances of the escape and the further fate of the traitor Lyushkov in the postwar period. And in 1978, a Japanese researcher and columnist Yoshiaki Hiyama published a book entitled "Plan of assassination of Stalin. An empirical analysis of the secret design of the Japanese army. ” It tells about the plan to use Lyushkov for the attempted assassination of Japanese agents on the life of the Soviet leader - Joseph Stalin.

Heinrich Lyushkov

Heinrich Lyushkov was born in 1900 in Odessa in the family of a Jewish tailor. After studying at the government primary school, and then at evening general education courses, he worked in the office of automobile supplies.

Under the influence of his older brother, he took part in revolutionary activities. In July 1917 he became a member of the RSDLP (b). In the same year, he joined the Red Guard in Odessa as an ordinary. Since 1918 - in the organs of the Cheka. He was the political instructor of the Shock Separate Brigade of the 14th Army.

After the Civil War, having passed a number of posts, in 1931 he was appointed head of the secret political department of the GPU (State Political Administration) in Ukraine. Then he was sent to Moscow to serve in the central apparatus of the OGPU (United State Political Administration). Lyushkov used the location of the People's Commissar of Internal Affairs of the USSR in 1934-1936, Heinrich Yagoda. He actively participated in high-profile investigations - the “Kremlin case”, the case of the “Trotskyist-Zinoviev center”. After which he was appointed head of the NKVD in the Azov-Black Sea Territory, which subsequently played a significant role in the Japanese operation to physically eliminate the Soviet leader. In early June 1937, for the zeal shown in the “purges”, he was awarded the Order of V. I. Lenin.

In 1937-1938 - Head of the NKVD Directorate for the Far East. Japan’s full-scale war in China has already begun, the selected Kwantung Army (Army Group), standing on the far eastern border of the USSR, was preparing for a future war against the Soviet Union, provoking border conflicts. In those years, the danger of the USSR becoming involved in a big war came primarily from Japan. Stalin showed increased attention to the situation on the Far Eastern borders of the country. According to some reports, the leader, before sending Lyushkov to the Far East, considered it necessary to briefly instruct him personally by inviting him to a 15-minute audience.

Soldiers of the Kwantung Army, 1938

Arriving in Khabarovsk, the new head of the NKVD began vigorously “eradicating the enemies” and purging the local UNKVD. He was charged with the creation of a right-wing Trotskyist organization in the internal affairs bodies of the Far East. Lyushkov was the main organizer of the deportation of Koreans from the Far East as potential Japanese spies.

Being an approximate and nominee of Yagoda, Lyushkov was suspected of belonging to a counter-revolutionary organization. Stalin was not informed of suspicions, having decided to interrogate Lyushkov and make sure that he was not involved in the conspiracy. But the question of political distrust of the State Security Commissioner was raised by the commander of the Far Eastern Army, Marshal of the Soviet Union V.K. Blucher.

May 26, 1938 Lyushkov was relieved of the duties of the head of the Far Eastern UNKVD allegedly in connection with the reorganization of the GUGB NKVD and the appointment to the central office. The People's Commissar of Internal Affairs N. I. Yezhov informed him about this in a telegram, where he asked for his attitude to the transfer to Moscow. Lyushkov realized that he would be arrested in Moscow. It was decided to escape and surrender to the Japanese, offering important information and other services for them.

However, according to published archival data, the decision was not spontaneous, but carefully thought out. Lyushkov prepared his escape in advance, two weeks before calling to Moscow, ordering his wife and her daughter to go to one of the European countries, ostensibly for her treatment. The necessary documents for leaving the USSR were prepared by Lyushkov in advance.

Sergey Igumnov. Eradicate spies and saboteurs! (fragment) 1937

Here is how the circumstances of the flight of the commissar of the NKVD are described:

“On June 9, 1938, Lyushkov notified his deputy of his departure to the border Posyet for a meeting with a particularly important agent. On the night of June 13, he arrived at the location of the 59th border detachment, ostensibly to inspect the posts and the border strip. Lyushkov was dressed in a field uniform at the awards. Having ordered the chief of the outpost to accompany him, he walked on foot to one of the sections of the border. Upon arrival, Lyushkov announced to the attendant that he had a meeting on the “other side” with a particularly important illegal Manchu agent, and since no one should know in person, he would go on alone and the head of the outpost should go half a kilometer towards Soviet territory and wait for the conditional signal. Lyushkov left, and the head of the outpost did as ordered, but, after waiting for him for more than two hours, he raised the alarm. The outpost was shotgun, and more than 100 border guards combed the area until the morning. More than a week, before news came from Japan, Lyushkov was considered missing, namely, that he was kidnapped (killed) by the Japanese. By that time, Lyushkov had crossed the border, and on June 14, 1938, at about 5:30 am near the city of Hunchun, he surrendered to the Manchu border guards and asked for political asylum. After he was transported to Japan and collaborated with the Japanese military. ”

Like many other traitors, Lyushkov tried to explain his betrayal not by selfish, but by political motives. In an interview with the Japanese newspaper Yomiuri Shimbun dated July 13, 1938, he convinced: “Until recently, I committed great crimes against the people, since I actively collaborated with Stalin in pursuing his policy of deception and terrorism. I really am a traitor. But I am a traitor only in relation to Stalin ... These are the immediate reasons for my escape from the USSR, but this is not the end of the matter. There are more important and fundamental reasons that made me act this way.

This is what I am convinced that Leninist principles have ceased to be the basis of party politics. I first felt hesitation since the assassination of Kirov by Nikolaev in late 1934. This case was fatal for the country as well as for the party. I was then in Leningrad. I was not only directly involved in the investigation of Kirov’s murder, but I also took an active part in public trials and executions after the Kirov case ... ”

Joseph Stalin

In reality, Lyushkov was an ordinary careerist and traitor, who did great harm to the Soviet state and people, transmitting to the Japanese special services extremely important information about the Soviet armed forces, especially in the Far East, about the deployment of troops, the construction of defensive structures, fortresses and fortifications. The Japanese received detailed, top secret information about the plans for the deployment of Soviet troops not only in the Far East, but also in Siberia, Ukraine, and military radio codes were revealed to them. The defector significantly weakened the USSR intelligence network in neighboring countries, betraying important Soviet agents.

In Japanese sources, the consequences and impact of the information transmitted by Lyushkov on Japanese military plans for the Soviet Union are assessed differently. On the one hand, it is believed that Tokyo decided to check the information transmitted to them about the shortcomings in the defense capabilities of the Soviet troops, which encouraged the Japanese command to expand the incident near Lake Hassan.

On the other hand, there is an opinion that, having learned the true alignment of forces and means of the opposing Japanese and Soviet groups in the Far East, the Japanese command was already planning much greater war with the USSR. It was unexpected for them that, according to Lyushkov, the USSR has a rather significant military superiority over the Japanese in the Far East.

Here's how the former officer of the 5th (Russian) intelligence department of the Japanese General Staff, Koichiro Koizumi, evaluated the information received from Lyushkov:

“The information that Lyushkov reported was extremely valuable for us ... In the information received from Lyushkov, it struck us that the troops that the Soviet Union could concentrate against Japan possessed, as it turned out, overwhelming superiority. At that time, that is, at the end of June 1938, our forces in Korea and Manchuria, which we could use against the Soviet Union, consisted of only 9 divisions ... Based on the information received from Lyushkov, the fifth section of the General Staff concluded that The Soviet Union can use up to 28 infantry divisions against Japan under normal conditions, and if necessary concentrate from 31 to 58 divisions ... The ratio in tanks and aircraft also looked alarming. Against 2000 Soviet aircraft, Japan could only deploy 340 and against 1900 Soviet tanks only 170 ... Before that, we believed that the Soviet and Japanese armed forces in the Far East were related to each other as three to one. However, the actual ratio turned out to be about five or even more to one. This made it virtually impossible to implement the previously drawn up plan of military operations against the USSR ... "

Disguised Soviet T-26 tanks

Such assessments even gave rise to thoughts whether Lyushkov was specifically sent as a defector to the Japanese in order to intimidate them with the might of the Soviet army and force them to abandon plans for an attack on the USSR. Which, of course, is unlikely. Moreover, Lyushkov proposed a plan for the assassination of Stalin and expressed his readiness to take part in the operation to destroy the Soviet leader himself.

In his book, Y. Hiyama reports that Lyushkov offered the Japanese a plan to kill Stalin. They grabbed him willingly. On duty, as head of the NKVD branch in the Azov-Black Sea Territory, Lyushkov was personally responsible for protecting the leader in Sochi. He knew that Stalin was being treated in Matsesta. The location of the building where Stalin took baths, Lyushkov well remembered the order and security system, since he himself developed them. Lyushkov led a sabotage group of Russian emigrants, which the Japanese transferred to the Soviet-Turkish border in 1939. However, a Soviet agent was introduced into the sabotage group and the crossing across the border failed.

Koichiro Koizumi denied Lyushkov’s participation in the operation, saying that "Tokyo refused his candidacy as an executor of a terrorist act against Stalin." Obviously, because he was a fairly well-known figure and would certainly have been recognized. Nevertheless, there is evidence that an attempt was made to transfer the Japanese subversive group across the Soviet-Turkish border.

Red army soldiers go on the attack. Surroundings of lake Hasan. One thousand nine hundred thirty eight

In one of the publications, the British newspaper The News Cronicle wrote about the failure of the terrorist attack on January 29, 1939: “As reported by TASS, on January 25, the Georgian SSR border guard killed three people trying to cross the border from Turkey. These three are Trotskyists, supported by the Nazis. The dead found pistols, hand grenades and detailed maps of the area.

The purpose of the criminal group was the killing of Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin, who was in Sochi. However, the border guards learned in advance about the criminal plan and exterminated the attackers. The People’s Commissar of Foreign Affairs Litvinov strongly protested that Turkey had become the base of anti-Soviet provocations. ”

It was such a statement by TASS, and whether it was about a sabotage operation prepared by Japanese intelligence using Lyushkov’s help, it’s hard to say now. But there is a lot of evidence that a plan for the physical destruction of Stalin on the eve of the war existed in Japanese literature and periodicals.

The Japanese did not hide the fact that shortly before the defeat of Japan, in July 1945, Lyushkov was transferred from Tokyo to the location of the Japanese military mission in Dairen (China) to work in the interests of the Kwantung Army. Japanese sources claim that after the Soviet Union entered the war and Hirohito announced that he would surrender, on August 19, 1945, Lyushkov was summoned to the head of the Dairen military mission, Yutaka Takeoka, who suggested he commit suicide in order to exclude disclosure if he was captured if he knew about Japanese intelligence. Since Lyushkov refused to shoot, Takeoka himself shot him and his body was secretly cremated.

The ceremony of signing the Act of Surrender of Japan. Representative of the USSR General K.N. Derevyanko signs the act. September 2, 1945

There is another version that Lyushkov was allegedly brought to Dairen to extradite the USSR in exchange for the captured son of the former Prime Minister, Prince Fumimaro Konoe. Upon learning of the impending extradition, he made an attempt to escape, but was strangled by Japanese officers.

Be that as it may, a fair punishment would have overtaken the traitor in any case, since back in 1939 Lyushkov was sentenced in absentia by the Soviet court to death.

Last edited:

Many generals and other high ranking officers were, but much of the decision-making top was old Tsarist era as well. And anyway Mannerheim himself made the big military decisions during the war. "Dreams of a Greater Finland", whether harbored by certain individuals or not, did not influence decision-making on either political or military level.

Btw, I just listened lecture of russian historian about M-R- Pact.

Also he noted that during negotations between USSR-UK- France about alliance against Germany in 1939 (before M-R Pact) Franz Halder arrived in Finland (Vyborg on the border with USSR) to participate in millitare training of artillery. USSR considered it asthreat to Leningrad

Intelligence fight: NKVD against ROVS (Russian All-Military Union) https://mywebs.su/tag/белоэмиграция/

White extremism in 1935-45

During the 1920s and 1930s, a fierce “twilight fight” - a secret intelligence war — was unfolding between the counter-intelligence of the ROVS (as well as a number of extremist organizations accompanying it) and the Soviet special services (OGPU - NKVD and the Red Army intelligence service). It covered almost all regions of the world and was conducted with a high degree of intensity: each of the parties showed intransigence and hatred for its opponent, the goals of the struggle were mutually opposite.

The task of the Soviet special services was the destruction of the foreign white movement in all its forms, primarily the extremist trend; the goal of the white-emigrant counterintelligence was to oppose the actions of Soviet agents and the Comintern, as well as to prepare an anti-Bolshevik uprising in the USSR.

It should be noted that the Soviet intelligence (INO OGPU - NKVD and the 4th Directorate of the General Staff of the Red Army) considered the fight against white military emigration to be "target number 1", which was repeatedly stated by the heads of the Soviet special services - Berzin, Menzhinsky, Trilisser and other plans of white the emigration to overthrow the Bolshevik regime in the USSR to a certain extent worried the Soviet government even more than the actions of the Trotskyists and supporters of the “right deviation” in the CPSU (B.), since in the case of the coming of White Guard extremists to the USSR, the Soviet chances the ruling elite didn’t even survive, and the White Terror would destroy the entire existing system to the ground. An insurmountable gap lay between the Soviet leadership and the white emigration, unlike Trotskyism, with representatives of which many figures of the Soviet special services and the state maintained secret contacts (for example, Blumkin, Tomsky, Preobrazhensky). Therefore, the Soviet intelligence acted most actively against the ROVS and the leaders of military emigration, using a large arsenal of means: bribery of extremism leaders, threats, kidnapping of activists, murders, incursions, compromising, etc. The White-emigre counterintelligence of the ROVS had immeasurably less opportunities, but it compensated for the shortage of money and weapons by fanaticism, ideological intransigence, and propaganda activity.

The OGPU, fighting against white terrorism, accumulated an increasing amount of information about the situation within the activist forces of emigration, introduced new agents to its environment. It knew that the leader of extremist combat groups was General A.P. Kutepov, supporter of white terror against the USSR. The OGPU had a plan for the abduction of A. Kutepov and his delivery to the USSR for an indicative trial of him. If this operation was successful, the OGPU could count on the growth of its authority within the country and the compromise of the idea of white terror both in the USSR and abroad, since it had the means to force any person to give the evidence that the OGPU needed. Had one of the ideologists and organizers of the White Terror policy made such testimonies, this would have dealt a serious blow to this theory in the eyes of emigration.

The emigrant press wrote that the OGPU had abducted Kutepov in order to arrange a show trial, then publish false repentance, bribe A. Kutepov and thereby decompose the Russian All-Military Union.

Foreign intelligence and the police of the countries of residence, in turn, closely monitored the activities of white emigre extremist organizations. The French secret police Sürte Generale, the Gestapo, and Polish counterintelligence kept the Russian emigrant extremist organizations in a latent state, allowing the possibility of their use for their own purposes in the event of a military conflict with the USSR.

The white-emigrant military-political extremism in the 1920s and 40s sought support from the Western special services, first of all, trying to get financial assistance and legal cover for their activities. In the 1920s, Russian emigre extremist organizations were actively looking for their place in the existing system of special services of Eastern and Western Europe, which would allow them to launch a large-scale anti-Bolshevik struggle and, accordingly, try to take revenge for the defeat in the Civil War of 1917-1920. The revanchist organizations of foreign Russia were of interest to foreign intelligence, primarily because of their contacts behind the Iron Curtain on the territory of the USSR. Western intelligence agencies heavily used white-emigrant organizations that had clandestine structures on Soviet territory. So, for example, the Polish U-6 residency, operating in the territory of the Belarusian Military District, used the help of the extremist organization of the Brotherhood of Russian Truth, which also had its underground cells in the region.

The coincidence at this stage of the interests of Russian extremism and foreign intelligence services conducting intelligence operations on the territory of the USSR allowed the emigrant revanchist unions to receive certain, financial and organizational support from the 2nd Bureau of the General Staff of Poland, Sürte Generale, German intelligence and a number of similar structures that pursued however, their own goals, very different from the ideas of the white movement.

Western intelligence, starting in 1920, began to use the counterintelligence structures of the white armies to organize intelligence and sabotage activities in Soviet Russia. So, in September 1920, the Estonian General Staff invited a number of Russian military leaders of the former North-West Volunteer Army to supply it with intelligence information. The proposal was accepted, and soon the White Guard counter-intelligence in the north-west direction actually turned into a branch of Estonian intelligence. One of the white emigre extremists who provided informational assistance to Estonian intelligence wrote:

“Our work could affect:

In the delivery of intelligence information about the fleet, the 7th Army, the Petrograd Military District and the political information of the Petrograd Commune. Moscow could have been weaker. Distribution of proclamations throughout the Petrograd, Pskov, and Yamburg districts.

The compilation and printing of the proclamations could take place here, and instructions from you are required to compile. In the creation of separate groups in the aforementioned region, which, with the successes and approach of the front, can destroy the rear of the Bolshevik troops.

In preparing people for creating detachments of 100-120 people for operations behind the Bolsheviks as the front approaches. ”

The counterrevolutionary structures of Western states secretly maintained fairly active contacts with White-emigre secret military-political organizations, mainly consisting of former Russian military. So, Soviet intelligence noted in 1923: “The Polish General Staff maintains close ties with White Guard organizations; according to February information, the Savinkov Information Bureau, headed by Colonel Pavlovsky, is, as it were, a branch of the 2nd department of the Polish headquarters, which through it carries out its intelligence work in Russia. General Dyakov, seconded by Wrangel to Poland, with the aim of uniting and attracting the interned Balakhovites and Peremykintsy (Savinkovites) to Wrangel’s side, enjoys the full support of the 2nd Division of the Polish headquarters.

The White-emigre counterintelligence in many cases carried out joint operations with Western intelligence agencies, which, however, was carefully hidden by the latter. For example, in 1936 in Istanbul, French counterintelligence, with the participation of Russian extremists, organized a special observation post, with the help of which Soviet diplomats and trade representatives, as well as employees of the Third Communist International were monitored. In November 1936, members of the Spanish delegation were sent to the USSR for the celebration of the 19th anniversary of the October Revolution, and a list of its members was received.

Thus, white-emigrant intelligence agencies gradually turned into informal branches of Western intelligence, helping them work in the “Russian direction”, providing military-strategic information, and in some cases participating in joint actions. Emigrant intelligence in many cases carried out purely intelligence tasks of the Western intelligence services, without any “ideological color”. For example, in 1921, information about the deployment of Soviet divisions on the Soviet-Romanian and Polish borders was obtained through the White Guard channels. ROVS ideologists easily explained such actions by the need to collect information for preparing a new military campaign against the USSR, in which case the white interventionist armies should have the necessary completeness of military information about the number and deployment of the Red Army, Soviet military doctrine, the direction of probable counterattacks of the Red Army, etc. . In addition, it should be borne in mind that Russian emigrant officers knew better the features, traditions and mentality of the Red Army commanders than foreign “Russian specialists” who eagerly consulted these Russian emigre colleagues.

In the first half of the 1920s, the remains of the Russian army of General P.N. Wrangel became actually a toy in the hands of England, France and the United States. Each of these countries has developed its own version of the use of white armed forces, in accordance with their own capabilities and geopolitical interests.

The Red Army Intelligence Agency was aware of the plans of Western governments regarding the White emigre armed forces: "Allied plans for the army: ... the British would like to use the army for their own purposes, namely: landing somewhere in the Caucasus, seizing the oil region and breaking off communications between Russia and East. There are also rumors about the desire of the British to use the army to block the movement of Russians in India. The French allegedly wanted to send an army to Romania in order to support the Romanians and attack the Ukraine. The Greeks allegedly wanted to use as a landing in the Caucasus in order to interrupt the communication with Mustafa Kemal Pasha. " This state of affairs did not leave an opportunity for leaders of Russian emigrant extremist organizations to pursue an independent policy, turning them into executors of someone else's will.

In 1920-21, the Cheka authorities, knowing that the leadership of the former white armies had set the officers remaining on Soviet territory to penetrate the Soviet apparatus and the Red Army, actively opposed these enemy plans, trying to prevent potential agents of influence in their structures. In a special instruction of the Cheka, it was said: “A lot of white officers, who occupy prominent responsible posts, arrived at all military institutions. For example, the senior adjutant of the head of the garrison is a former lieutenant of the commandant battalion of Sevastopol.

It is necessary to make an accurate check in all military units and institutions, in hospitals and with private employers. ”

After the occupation of the territory of the Crimea, Ukraine, and the Far East by the Red Army troops in 1920-22, special bodies of the Cheka-GPU conducted mass inspections of the male population of draft age in order to identify former participants in the white movement. In the context of the emerging totalitarian regime, the “social filter”, through which everyone was forced to go to the Soviet service and become citizens of the RSFSR, also performed the function of countering emigrant extremism, limiting its social base.

In 1920-21, the Cheka and the Red Army conducted “merciless red terror” in Crimea with the goal of destroying all underground structures of the White Guards, eliminating their agents, and defeating the counter-intelligence network. In this case, they used both “special methods” (organizing their own intelligence in the enemy camp, identifying scouts, etc.), as well as open large-scale terror against all persons “socially close to the white movement”. For example, the Special Division of the 9th Red Army Division “had to register in the two cities of Kerch and Feodosia all the remaining White Guard officers and officials. At the time of registration, Comrade Shock Group Commissioner Comrade Arrived. Danishevsky with instructions given to him about the White Guards. Having started, the Troika, consisting of Danishevsky, Dobroditsky and Zotov, performed the following work: Of the White Guards registered and detained in Feodosia in an approximate count of 1,100, 1,006 people were shot. 15 were released and 79 people were sent north.

The officers and officials detained in Kerch were approximately 800 people, of whom about 700 were shot, and the rest were sent north or released. Moreover, no more than 2% of those released were released - those who were accidentally detained, never served, but who appeared either at the request of the party committees, or because they belonged to the underground, although they were officers. ”

Such measures were effective primarily in relation to such forms of white-emigre extremism as guerrilla-insurgent war, sabotage actions against workers of the local Soviet party and state apparatus, certain sorties and landing on the territory of the RSFSR. They did not affect the organizational and ideological core of the white emigre revanchism abroad (Paris, Berlin, Belgrade), opposing only certain forms of its manifestation.

Wrangel intelligence in 1920-22 was forced to actively solve the problem of the prompt delivery of its agents to Soviet territory. At the same time, auxiliary means were used - artisans of fishermen, smugglers, etc., as well as an agent network left in Soviet Russia after the evacuation of the Russian army gene. P.N. Wrangel. According to the intelligence information received by the Soviet intelligence, the operation to send White Guard agents to the territory of the RSFSR looked something like this: “All the work of the head of the point is that he collects groups of agents, then sends him to the headquarters of captain 1st rank Mashukanov, who drops them in right place. But in addition, an artel of fishermen was hired in Yenikal, which landed agents on boats north of the village of Chushka (Taman). ” However, in such an active regime, White Guard intelligence could operate for a rather short period of time: the strengthening of the Soviet system and the closure of borders already in the mid-1920s made it extremely difficult for white agents to penetrate behind the Iron Curtain.

The leaders of the ROVS and a number of other extremist emigrant organizations in the 1920s and 1930s tried to create “windows” on the borders of the USSR for the transfer of saboteurs, scouts, and white propagandists to Soviet territory. However, most of these attempts ended in failure: the special bodies of the NKVD and the 4th Directorate of the Red Army, who controlled most of the white emigrant political structures under their information, immediately learned about white propaganda attempts to cross the border and arrested them. White militants and agitators failed to establish a systematic crossing of the Soviet border, and the information field of the USSR remained closed to white propaganda.

The main areas of activity of intelligence of the Russian army gene. P.N. Wrangel formed back in 1920 while it was on Russian territory. Subsequently, the intelligence of the ROVS collected information of approximately the same nature. In special documents of the Cheka, devoted to the organization and work of Wrangel intelligence and counterintelligence, it was noted that “intelligence, dividing work into resident, deep rear, front-line and walkers, entrusts:

At first:

1. Information on working, national, economic, transport, religious status and instruction of the Soviet government.

2. Lighting on the ground and in general. Operational work.

On 2:

1. Reconnaissance of the rear militarily.

2. Politically.

3. The mood.

On 3:

1. An explanation of the mood of the immediate rear (population).

2. An explanation of the morale of the troops.

3. The number of them.

Quality condition.

Command staff (are there former officers of the General Staff and their last names).

Armament (the number of machine guns, guns, armored trains and armored vehicles).

Air fleet (number of vehicles, system, power, weapons and lift), as well as personnel, surnames and its base.

The location of the headquarters of the divisions and military bases that feed the front.

The power of artillery.

On 4: 1. Communication with residents.

Deep rear tasks fall more to the share of intelligence of the headquarters of the commander in chief and corps, as well as resident tasks. Front-line intelligence is conducted by the headquarters of the corps and divisions. The latter have more lightweight agents - “walkers,” who are sent by the headquarters of the commander in chief and corps. Particularly special tasks come only from the headquarters of the commander in chief (expelling agents with the specified tasks). "

By the mid-1920s, most of the Wrangel intelligence system ceased to exist, only a few continued to maintain contact with the ROVS and foreign extremist organizations, mainly former police officers or “coastal counterintelligence”, smugglers who adapted in the criminal world of the NEP period.

The ROVS leadership in the 1920s and 1930s made repeated attempts to create a White Guard underground on the territory of the USSR so that the interventionist army that appeared on the Soviet borders would receive support from the "fifth column", and the Red Army, accordingly, would be stabbed in the back. The military leaders of the Russian foreign countries are Generals P.N. Wrangel, P. Shatilov, A. Arkhangelsky - sought to find supporters among the command staff of the Red Army. With the help of their former comrades-in-arms of the period of the First World War of 1914-18, the leaders of the ROVS dreamed of organizing an anti-Stalinist plot and carrying out a military coup that would result in the overthrow of the Soviet regime and the establishment of a white dictatorship in the country.

It was through such fellow soldiers in the early 1920s that the white counterintelligence tried to establish communications and attract them to secret work against the Soviet government. In turn, the Soviet special services of the Cheka and the GPU, knowing this, took countermeasures, identifying the addresses and surnames of such persons, establishing surveillance over them. For example, in 1920, assuming that one of the significant leaders of military emigration was General P.S. Makhrov illegally crossed the Soviet border and came to Petrograd to organize clandestine work, the Cheka gave the order to organize surveillance of the apartment of his friend Colonel General Staff of the Red Army: “If Makhrov really went, then without doubt he will use his great friend Colonel General Staff Boris Nikolayevich Kondratiev in Petrograd living on Vasilievsky island. "

Extremist military organizations of the Russian foreign countries, primarily the EMRO, developed numerous plans for spreading their influence in the USSR, projects for the destruction of the Soviet party and state apparatus from the inside, tried to launch a propaganda war to discredit the regime. The author of the note for the leadership of the ROVS summarized its contents with the following statement:

“Preparatory work should be carried out in three directions:

Penetration into the apparatus of power, mainly into the Red Army.

The incitement of internal party strife and the splintering of the Communist Party.

Supply of the population with anti-communist propaganda literature. ”

The leaders of the foreign extremist movement were most interested in Soviet responsible workers, whom the leaders of the ROVS tried to entice over with the promise of amnesty in the future and attracting them to military and public service "after the overthrow of the Bolshevik regime and the revival of Russia." The ROVS secret instructions prescribed to their secret agents "a cautious approach and networking with those in senior positions in the Red Army and in civilian administration, both non-partisans and communists." In case of refusal to cooperate, emigrant extremists threatened them with white terror. However, the efforts of the white counterintelligence did not yield results: under the conditions of a totalitarian regime, control and surveillance, even the slightest suspicion of having ties to emigration quickly led such adventurers to the Gulag. The creation of a white-emigre “fifth column” in the USSR, thus, proved to be an axis impossible.

The idea of a “silent counter-revolution” remained popular among the emigrant community until the mid-1930s, when the obvious victory of Stalin and his policies (industrialization, collectivization, liquidation of the opposition) left military extremism no chance of success in the USSR.

Although the Soviet secret services noted that the "counter-revolutionary elements" in the USSR "with the intensification of the class struggle in the country will try to take advantage of certain parts of the Soviet apparatus," the OGPU-NKVD managed to isolate emigration "from sources of influence, from mass social forces ...", and the absence in the USSR of its lobby and influence groups turned Russian emigrants into extraneous spectators of tectonic processes that took place in the Soviet political system.

The fantastic plans of the leaders of the military emotion sometimes provoked ironic smiles of former Russian diplomats, who were well versed in the alignment of political forces in Europe and the Far East. So, for example, the former imperial ambassador to Great Britain E.V. Sablin wrote in March 1937 to V. Maklakov: “Of course, General Denikin is right in theory, who never tires of repeating that the main task is to“ overthrow the Bolshevik power and keep the army intact ”, but the question is: vi makht man das (how is this done "- German) in practice and how can relatively few and scattered emigrants do this."

A special place in the system of extremist organizations of the Russian foreign countries was occupied by counterintelligence structures of the ROVS and BRP. General P.N. Wrangel already in 1920-21 began to create a conspiracy information network, which was supposed to serve the counterintelligence and sabotage structures of the "Russian army in exile." So, in 1921, at the headquarters of the commander-in-chief of the former Russian army, an "Information Bureau under the name" D. "and" L. "was created (based on the initial letters of its leaders: Prince P. D. Dolgoruky and N. N. Lvov). The bureau issued ballot papers printed on a rotator and sent them to military units, to Russian emigrant newspapers, oriented to the right-conservative part of the Russian foreign countries.

White-emigrant intelligence in the 1920s and 1930s identified political intelligence as one of its priority areas of activity, in particular, opposing the “plans of the Comintern for preparing the world revolution”, monitoring the leaders of European Communist and Social Democratic parties, identifying agents of the OGPU-NKVD in the emigrant environment, etc. So, the counter-intelligence of the ROVS collected "information about the Bolshevik plans for the creation of a revolutionary army in Europe." Under the ROVS divisions, special counterintelligence divisions were created, the task of which was to counter the operations of the Soviet special services in the territory of recipient countries.

A feature of military emigration as part of Foreign Russia was the presence in its composition of a large number of military intelligence officers, high-level professionals who in the 1920s and 1930s were in demand by foreign intelligence services. Many heads of the counterintelligence departments of the white armies, primarily the Russian Army gene. P.N. Wrangel, in 1920-22 they switched to the regular service of Western intelligence. So, in the report of the French counterintelligence, “German Activities in Constantinople and the Middle East,” there is information about German intelligence agents from former officers of the tsarist army ... ”

Russian military emigrants in the early 1920s easily found a common language with representatives of European intelligence, primarily German and French, while actively using contacts and contacts that were established during the First World War of 1914-18, which, after the formation of the Russian emigrant diaspora received a different projection. So, as regards the relations between the counterintelligence of the ROVS and the German special services, from the irreconcilable opponents by the mid-1920s they turned into temporary allies. Western intelligence agencies used information received from deserters from the Red Army, many of which were so-called. "Military experts", i.e. received a military education until 1917, or even served for some time in the white armies. So, for example, in 1931, the French counterintelligence compiled a "Certificate of the internal political situation in the USSR" on the basis of the testimony of "a former white officer who entered the Red Army and deserted from it ..."

In 1922-23, the Bulgarian special services launched an active struggle against the white emigrant counterintelligence, which created an extensive network in Bulgaria that included all the intelligence structures necessary for conducting large-scale diversion work: safe houses, secret warehouses, weapons, “windows” on the border, observation posts, etc. .P. In 1922, an article was published in the Polish newspaper "Worker" about the disclosure of the "reconnaissance Wrangel network in Bulgaria." Counterintelligence P.N. Wrangel in Bulgaria had two main tasks: collecting information about Soviet Russia and preparing the intervention, as well as the struggle against the revolutionary democratic movement in the country, in particular against the Istanbul government. The counterintelligence structures of the ROVS and other white-emigre revanchist organizations collected information about the situation in the Red Army, the state of the material and technical base of the Soviet troops, the maneuvers conducted in the USSR, trying to identify at least some traces of the activities of the anti-Soviet underground organizations in the Red Army. At the same time, what was desired was presented as real, and quite ordinary “everyday” incidents were given a political character, an epoch-making significance.

“In the Red Army,” the ROVS observer wrote, “in early December [1936] during the maneuvers of mechanized Soviet units (about 100 tanks and armored vehicles) near the village of Pokrovka (the confluence of Halki and Argun in the Amur Region), one of the tank detachments (6 tanks) was blown up, as it turned out by the investigation, infernal vehicles. "The Soviet authorities suggest that this is the work of the" White Guards "who have their own organization in parts of the Far Eastern Red Army."

Riot, uprising in the Red Army - a favorite topic of most publications in emigrant military newspapers and magazines in the 1920s and 30s. The White-emigrant military-political extremism primarily set out to fight for the “minds and hearts” of the Red Army soldiers, who, according to the ideology of the ROVS, were to become a building material during the creation of the new Russian army, which “grew up in many ways from the Red Army”.

In the 1920s and 1930s, Western intelligence agencies supplied Russian extremist organizations with information about the internal situation in the USSR, information about Stalin’s struggle against opposition trends in the CPSU (b), the prospects for a social explosion in the USSR, etc., which were received through their own channels, in many cases - undercover. For example, in 1923, French intelligence received the secret GPU newsletter about unrest among workers and employees of various enterprises of the USSR that demanded higher wages, with which the leaders of the Russian military emigration were privately acquainted.

It should be noted that the counter-intelligence of the ROVS carried out an extremely biased assessment of the information received by it, acting on the principle “the worse for the fact” if it did not correspond to the artificial and far-fetched schemes developed in the bowels of the ideological laboratory of the ROVS.

With the EMRO in the 1920-30s. There was an information and analytical department in which information was carefully collected on the internal situation in the USSR, the state of the Red Army, the mood of the masses of the population, and political trials in Moscow in 1929-1939. etc.

Sources of information of white emigration were:

1) Soviet mass print media: books, brochures, newspapers. "The factual material relating to the Bolshevik era is gleaned ... mainly from Soviet publications and, above all, from data from Soviet statistics." At the same time, it was noted that information about the Soviet economy reached emigration “in a random and often erratic form”;

2) program documents of the CPSU (b) and texts of speeches by the leaders of the party and the Soviet government - I.V. Stalin, M.I. Kalinin, etc. At the same time, it should be noted that the reliability of the information received by the White Emigrant counterintelligence was very low.

This is due to the following reasons.

Intelligence ROVS did not have access to operational secret information of the Soviet special services and government agencies. ROVS analysts poorly imagined Soviet reality and, therefore, often were unable to draw the right conclusions from the information received. Information about the situation in the USSR was obtained selectively, haphazardly and did not create a holistic picture of life in the Soviet Union. In many cases, the wish was presented as valid when, on the basis of insignificant facts, "epoch-making" conclusions were drawn about the proximity of the fall of the Bolshevik regime.

Activists of Russian emigrant military-political organizations felt close attention from the Soviet special services, constantly urging participants in the anti-Bolshevik movement to be vigilant to carefully implement all necessary conspiracy measures. “The Bolsheviks vigilantly follow us,” wrote the ROVS instructor in 1936, “their agents and observers got into all of our organizations. Subtle and well thought out work on the decomposition of emigrant masses is being imperceptibly conducted. ”

Indeed, Soviet intelligence made considerable efforts to disintegrate Russian military emigration, systematically organized a leak of information compromising the leaders of emigrant military unions and societies, and sought to disorient the emigrant youth, craving information about the internal situation in the USSR.

Soviet intelligence considered work against military emigration in the 1920s the main focus of its activities. In 1927, at an enlarged meeting of the Soviet special services of the INO OGPU and the Intelligence Service of the Red Army, it was decided to intensify operations to neutralize military emigration.

The largest operation successfully carried out by the OGPU in the direction of “white emigration” was the creation of a fictitious organization under the code name “Trust”. She was given the task of uniting all the white emigrant politically active forces around herself, mass introducing provocateurs into their composition and thus gaining the ability to direct the activities of such organizations in accordance with the directives of the OGPU.

The history of the “Trust” is as follows. In 1922, an OGPU was arrested by a certain P. Selyaninov-Opperput, associated with the NSZRiS B. Savinkov. Saving his life, he agreed to take part in the large-scale operation developed by the organs of the OGPU, aimed at identifying and destroying the white emigre underground in the USSR and abroad. A.A. was also connected to the case. Yakushev, a major engineer who worked in the USSR as a specialist. He was arrested on charges of organizing a counter-revolutionary conspiracy and espionage in favor of the Supreme Monarchical Council. Being in 1922 abroad, A.A. Yakushev had meetings with prominent figures of the white movement and advised them on the internal situation in the USSR. According to him, the power in the country after the fall of the Bolsheviks had to go to those circles of the white movement that did not emigrate abroad, but remained underground in the USSR. As such an organization, he called the ICRC - the Monarchist Organization of Central Russia.