Where did you find a SWEET five-year old? That surely is an oxymoron. Is there any chance that Sis the Basilissa is in a matrilineal marriage? Have fun, keeping your dynasty in power with the sweet 5yo. I foresee him knocking his regent off the balcony with his hobby horse. Thank you for updating.

Empire on Wings (Orthodox AAR)

- Thread starter FondMemberofSociety

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Threadmarks

View all 31 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Redux 3: My Crime would surely come a Second Time Redux 4: Lithuania Orthodoxia Reduxia Redux 5 The King in the North Redux 6 The Death of King Romanos Redux 7 And so Kestutis' Era Begins Redux 8 Rebellion Breaks Out Redux 9 Peace of a sort I am sorry this is how Empire on Wings endsOf course not. That is kind of difficult given the power of House Makedon.Is there any chance that Sis the Basilissa is in a matrilineal marriage?

Oh you have no idea what he (his regents, more precisely) will do.I foresee him knocking his regent off the balcony with his hobby horse.

- 1

Redux 8 Rebellion Breaks Out

EOWR8

Rebellion Breaks Out

Rebellion Breaks Out

For all that Romanos I of Lithuania had been a mediocre ruler before and after his dramatic change of heart in the Year of Our Lord 936, the principles of politics before the development of a mature bureaucracy weren't that hard even for him to master.

It had to be simple, if simply for the fact many, if not most, of its participants were illiterate: expand the power of the ruling family, the ruler first, then especially the power of the designated successor. This overall principle, which would last for some three thousand years, would enter an even more bloody phase at different times in different regions, which would last around four to five hundred years.

Though this particular phase of politics was on the decline in 10th century China, it was unfortunately now in full swing in Lithuania - the phase where the delicate balance between nobles and the king could violently swing one way or the other, due to the development of rudimentary bureaucracy. Nobles could gain power to stay the hand of the king - but they must be part of his court and government to access that power. Royal power can make and break any noble house - but it needs the assent and cooperation of the nobles as a whole.

At this phase, the ruler has, to use very broad strokes, two choices: expand the power of all adult males of the ruling family, and bear with the bloody internecine struggles that result from multiple sons contesting the succession; or to limit the power of the ruling family to avoid the tragedy of fathers and sons and brothers killing each other and end up with the whole family getting executed by a successful usurper.

Now, one may ask: Why not empower only the crown prince? If none of his brothers believe they could stand to inherit by the sheer power he wields, wouldn't all this trouble be solved?

Why yes, it would. A little extra trouble being the old king would be solved alongside as a problem.

So true to the tides of the age he brought about, Romanos made landed lords out of all his sons, his brother, his brother-nephew, and an extra pair of nephews. With this move, his house had unchallenged power throughout Lithuania. But to maintain power, he needed to move more pieces.

On his deathbed, he designated his brother Gimbutas as the primary regent for his young son, hoping his brother would last just long enough for his son to grow up. The regent was over 50 years old now, and as an active combatant, there was always a risk of him dying untimely.

(The unlanded son of Gimbutas stands to inherit his counties in the duchy of Lithuania. I was a good uncle as Romanos.)

Next, with his eldest daughter married to the Basilius of the Roman Empire, the house of Romanos had one trump card even if internecine struggles spiral out of control and the house finds itself greatly weakened: the alliance of the most powerful Orthodox ruler in the world.

Finally, Romanos let the richest man in his realm tutor his son. Grand Mayor Mantvydas was honored by the suggestion, and the question whether he was aware he was another piece played by Romanos to maintain a delicate balance of power within his realm ... did not really cross the old and ailing king's mind.

Naturally, like any system of power which hinges on the stability of personal relationships, the entire tapestry weaved by Romanos was first unknit by a minor event.

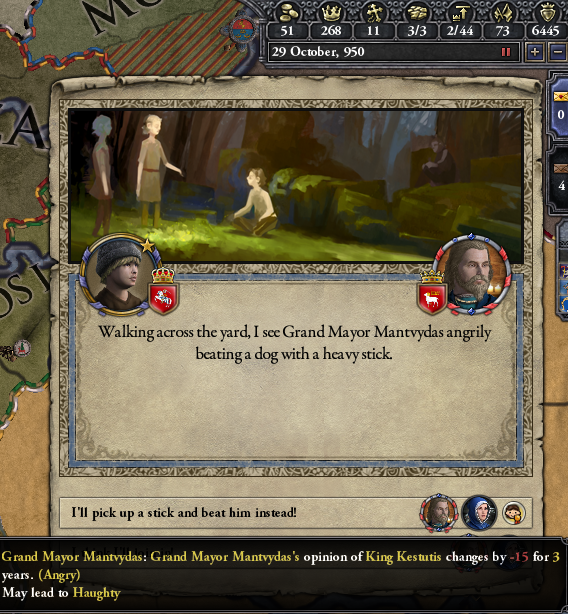

Little Kestutis raised a stick to beat his tutor, since as a child, he has no concept of "should"s and "should not"s, such as "you should not beat up your tutor with a stick". A man who flew to the top of newborn Lithuanian feudal society with few setbacks after the process was said and done - and none before that - the Grand Mayor did not take the child-king's insult lightly. The resulting altercation blossomed into a full-blown rivalry between man and boy, vassal and liege.

Which soon blossomed into an act with further consequences. For all his posturing, High Chief Piotr of Pruthenia, not of the house of Romanos, simply did not have the power to take on a united Lithuania even if her king was still a child. Now, lucky circumstances ruptured the delicate balance of power, which was Romanos' legacy, and had pushed the richest man in the realm into his embrace, a fact which greatly bolstered his power, and he did not hesitate to make use of it.

Of course, the king's remaining regents were still very confident in their ability to put down a rebellion joined only by Pruthenia and Gotland. Despite Princess Pajauta being married to the most powerful ruler in the Christian world, that power was allied to Vilnius, which meant funnily the claimant having her claim pushed was actually allied to the defending title-holder.

And thus war began, unfortunately - perhaps, fortunately - the first of many challenges that would cross Kestutis' life.

Not too long after the outbreak of the civil war, foreign news coursed into Vilnius as it was something that aught be celebrated across Christendom - the Umayyad infidels that pushed into Aquitaine had been overwhelmed by Papist forces, the flower of them all being King Eadred of England. The gains he made in this land were given to a Liudolfinger, which meant the royal house of Germany now enveloped the kingdom of France from the east and south.

The problem was all that had little to do with Lithuania.

Another threat looms on the horizon, breathing down the neck of the king's new regency council: a High Chief from among Lithuania's hated Norse foes. The sooner they could wrap up this rebellion and rebuild, the better their chances of defeating the monstrous host Norse war-summons could build up. The news coming from up north was almost as troubling as those coming from the west, where the royal host was clashing with the rebels.

Now, "new regency council", you said. Why would the boy king Kestutis need a new regency council, when they already had the old, diplomatic, reliable Gimbutas at their helm. Surely he could knit together the vassals still loyal to Vilnius, as the temporary nexus of royal power Romanos hoped he could be, as the leading member of House Palemonos alive? Surely he would remain the bedrock of the balance of power set up by the late King of Lithuania?

Would he?

NO

- 1

- 1

Well, the nobles seem to be scheming for power...

The Lithuanians seem to have adopted the Frankish approach. Let's hope it ends better for them than it did for the Holy Roman Empire or the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in OTL. Will primogeniture be adopted eventually?

The Lithuanians seem to have adopted the Frankish approach. Let's hope it ends better for them than it did for the Holy Roman Empire or the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in OTL. Will primogeniture be adopted eventually?

- 1

I'm trying to get Kestutis run for elective atm, but as you can see at this particular stage succession is much less of a problem than keeping his head on his neck.Well, the nobles seem to be scheming for power...

The Lithuanians seem to have adopted the Frankish approach. Let's hope it ends better for them than it did for the Holy Roman Empire or the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in OTL. Will primogeniture be adopted eventually?

- 1

Redux 9 Peace of a sort

EOWR9

Peace of a sort

Peace of a sort

The rebel coalition was quite fearsome, but on closer scrutiny, the rebels were still reliant on infantry, especially the heavy infantry generations of Lithuanians have taken pride in. Yet King Romanos brought about a great tide of change, one that echoed even in military spheres.

Long story short, on a well-chosen battlefield of plains, the royal heavy cavalry charged into the rebel infantry, shattering lines and morale, winning the day in the name of the little king. The revolt was soon over after a few small battles mopping up remnants and a lot of sieging.

The new regency council soon decided to imprison most leaders of the rebellion indefinitely, with only one major exception made. The elderly Gimbutas, ex-chief regent, was released on account of his contributions to state, his age and as a show of unity within the royal family. While not exactly pleased with his sojourn in prison, Gimbutas was forced to acknowledge the kingdom remained in the good hands of his brother-son Montvilas, who had replaced him as chief regent after the chief's rebellion.

Another important rebel, the Grand Mayor Mantvydas, would be kept under especially close watch, as the first act of the boy king wielding his power was to order Mantvydas "be kept from the light of the sun forever". On account of the Grand Mayor's obviously terrible relationship with his liege, Montvilas sanctioned the order, acting as chief regent.

Curiously, while taking over the education of his nephew-cousin and king, Montvilas did not demonstrate his usual shrewdness, allowing a bully to sneak into the king's life, causing him unspeakable torment whenever the eyes of adults were turned. As a sweet, sweet boy, King Kestutis chose to avoid conflict, trying to ignore the bully. This would improve the king's "people skills", an improvement that would do little to help him now except keep his heart at peace.

Taking a stroll in the royal grounds after his lessons one day, the boy king was startled by the sound of movement coming from bushes next to him. He calls out in its direction, but if the source of the sound was human, his attempt at contact was ignored.

(I think this is part of the evil nanny events, since the event character portrait is a French maid.)

Fortunately, it was not the scuttling noise made by a careless assassin, but the rustling caused by a bird that had apparently fallen out of its nest. As a sweet and kind boy, King Kestutis took the bird into his personal care. Such an act earned the praise of priests in charge of his education, raising a reputation of piety for the king.

Near the end of the year, the regency council of Prince Romanos, Duke of Polotsk and the king's oldest younger brother, decided that situation in the region had sufficiently developed to warrant a new mode of management. News soon reached Vilnius that the duchy had begun to feudalize and construct castles.

(Sheer geographical proximity should demonstrate how important any development in Polotsk is for anyone ruling from Vilnius. In case you don't know, Vilnius is the county/province with Lithuania's royal banner - red field, white horseman - flying on top of it.)

Another curious development was the pregnancy of Queen Mother Anele, mother of the 10-year-old King. As a gentle and kind soul, Kestutis naturally spent time with his mother, who was suffering from a troubling pregnancy. Some people believe this was merely a child's natural affection for his mother, so his kindness was not widely accepted as a trait.

(I ran a little check-back to see who the queen mother married after the old king's death. The result was this man, and as he was an unremarkable, unlanded courtier without notable connexions AND who was more than 20 years her senior ... it was just so confusing how the marriage happened.)

After rolling the drums of war over Lithuania's head for so long, the king of Svjpod had unfortunately missed his chance to pounce in during the rebellion and greatly warmed the king's tenth birthday by sending 3400 infantrymen to be defeated and captured in foreign lands. The captives of war were paraded across the royal square on the happy day, mimicking - to the limits of Lithuania's finances - the pomp and circumstance of a proper Roman triumph, one of the many things learned from their brothers in Orthodoxy.

Last edited:

- 1

Part of the what now??? I guess nothing should surprise me anymore, this is ck2 after all.I think this is part of the evil nanny events

- 1

The demon child-related evil nanny events. Turning off demon worshipper societies does not stop demon child events, so I see things when suspicious French nannies appear for no apparent reason.Part of the what now??? I guess nothing should surprise me anymore, this is ck2 after all.

- 1

Well, the rebellion has been defeated, and feudalism is becoming adopted...

The king seems like a good soul - let's hope that he can still govern well and not be crushed by the demands of a king...

The king seems like a good soul - let's hope that he can still govern well and not be crushed by the demands of a king...

- 1

Good job with the rebellion. I am familiar with the devil spawn child as I have lost a game because of one, but I have never seen the evil nanny. Also I have seen kids knock their tutors/regents over balconies. Thank you for the update.The demon child-related evil nanny events. Turning off demon worshipper societies does not stop demon child events, so I see things when suspicious French nannies appear for no apparent reason.

I am sorry this is how Empire on Wings ends

NOTICE

Due to unforeseen and fatal hardware error, all savegames and screenshots of Empire on Wings has been lost. If mods see this, please close the thread.

Due to unforeseen and fatal hardware error, all savegames and screenshots of Empire on Wings has been lost. If mods see this, please close the thread.

- 1

I am sorry to hear that the evil nanny visited your computer. Since you are Avon's religious advisor, please stop by or send me a PM when you start your next AAR so that it can receive a shout-out.

Threadmarks

View all 31 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode