II.

16 January 1416 – 11 December 1417

.png)

16 January 1416 – 11 December 1417

Jan Hus was suspended from his duties as a priest in the Orthodox Church of Moravia in late 1415, pending a summons to Velehrad to answer for ecclesiastical crimes, including the suspected promulgation of heresy. There was little doubt that the uprising in Bohemia against the king, and the involvement of self-proclaimed Johanité[1] on both sides of the civil war, prompted this disciplinary action. The priestmonk asked from Kráľ Róbert, and was granted, safe passage from Prague, across rebel-held lines into loyalist-held territory to obey this summons and answer the charges against him. The bishops of the Orthodox Church of Moravia, with Archbishop Prokop taking the position of primacy, laid out the charges against the Priestmonk Jan Hus as follows.

- That, in his tirades against the lax morals of Prokop’s predecessor Archbishop Elisei and his calls for a higher standard of morality among the priesthood, he knowingly promulgated the ecclesiological heresy of the 4th-century African Donatus Magnus;

- That he had called for an abolition of the sacramental priesthood and promulgated a radical doctrine of individual interpretation of Scripture;

- That he had called for unilateral reforms to the Liturgical rubrics to bring them into conformity with the common vernacular, in breach of historical usage;

- That, in supporting turmoil within the Moravian realm and inciting actions against lawful secular rule, he was in breach of proper Church discipline.

This local council of the Orthodox Church of Moravia was given the blessing of the (extraordinarily young) Ecumenical Patriarch Sabbas of Constantinople, who himself attended the proceedings—although as a visiting bishop within Moravia, he did not arrogate to himself any right to speak on behalf of the whole Church at this particular council.

When Jan Hus arrived at the council, he was treated with consideration. Jan’s personality was fairly abrasive, and he at first bristled against the charges that were laid upon him. But after some time, he stood before the bishops with great poise and interior calm. He answered the charges:

‘Holy fathers, venerable labourers in the vineyard of Christ, I beseech your pardon. I did speak broadly, and with great anger, against the various manifest iniquities of which the former Archbishop Elisei (may God forgive his sins and make his memory to be eternal) was guilty in life. However, I am at pains to remember any occasion upon which I pronounced that his sins made him unworthy to impart the Holy Gifts to the people. May Christ forgive my sin, if I led even one person into confusion with my words spoken in temper! I utterly despise and condemn the Donatist doctrine.

‘With regard to the second charge, I hold that it is a falsehood. Let the Just Judge of all—who on that dread day shall terribly judge me, the sinner and unprofitable servant—be my witness. Such an enormity has never entered into my heart, let alone into my words. For I know many priests whose shoes I am not worthy to take off, and whose heels—on account of their holy conduct—I should like to kiss[2]. I have only ever held that priests must never accept payment in exchange for the Holy Mysteries; and most of the priests of my acquaintance already obey this stricture.

‘That it is my reasoned desire that the Liturgy be celebrated in the Czech language, the language which most common Češi speak, is no great secret. If Saint Mark could teach in Latin; and Saint John of Patmos in Greek; Saint Matthew in Hebrew; Saint Luke in Syriac; Saint Simon in Farsî; and Saint Bartholomew in Aramaic—then how comes it that the Czechs may not hear the word of God in a language nearer to them than the Church Slavonic of six hundred years hence? But although I desire such reforms, I have not undertaken to implement them myself without the blessing of Your Holiness, my bishop. May God forgive my stubbornness and arrogant self-will, if I allowed this temptation to fester in any man’s heart.

‘With regard to the fourth charge, that I have stirred up enmity and envy against the lords of the Moravian realm, I answer: it is true that I have enjoined and encouraged lords and ladies to be merciful to their bowers. I have also publicly admonished those who have abused the authority with which God has entrusted them. That great lords host lavish feasts with lewd dancing and frivolous games is a stumbling-block to many men and women. And it is worse still that some among the Moravian lords extort and plunder, in the most shameless and vicious fashion, wealth in the form of various unjust duties and levies from simple folk: commoners who know no defence in law and whose only help is in the Lord Jesus Christ! Stealing the very crumbs from people who have only that! And yet, I do attest, there are great lords and ladies who are radiant in their souls with the light of Christ’s love, and they show it each day to those they meet, of high or low station in life. With such authorities I have no quarrel, and I pray God to protect and keep them.’

With Jan Hus having delivered his apology, the bishops deliberated.

In the end, of the four ecclesial charges of which he stood accused, the Priestmonk Jan Hus was found guilty only of one—the last, his opposition to lawful secular rule and breach of proper Church discipline. On account of this, his suspension from the priesthood was upheld. He was exhorted to return to his monastery in seclusion under penance from his abbot, and refrain from speaking in public or from celebrating the Divine Liturgy for a period of seven years, at which time he would again be examined. If he had repented of his lack of discipline, his suspension would be lifted. If not, he would be defrocked[3].

~~~

The followers of Jan Hus among the Nositelia Viery, at the same time as he was facing these ecclesiastical charges in Velehrad, were busy in the north of Bohemia. They were fighting against the rebellious Bohemian nobility, whose authority Jan Hus was convicted of resisting. The irony was not lost on the Johanité, though most of them bore it stoically.

There was one squabble which took place over the issue, however—publicly, and in full view of the camp. One of the Nositelia, a partizan of Jan Hus by the name of Svätoslav (who, like his master Žižka, wore a patch over one eye), erupted into a shouting match with the notably devout gentry lad Vojmil—who took up the position of the Church. The two of them were at the point of blows when the Kráľ himself burst in upon them.

‘Y—y—you—you so—sorry exc—c—cuses for s—soldiers!’ Robin raged, his face turning red. ‘Th—the Ch—Ch—Church has been wuh—wise in up—up—pholding d—discipline while m—muh—maintaining unity! And F—Father J—J—Jan has wuh—willingly ret—t—turned to Praha, acc—c—cepting the Ch—Church’s j—judgement! Wuh—would you l—learned f—from their example! Wh—why are w—we even f—fighting this war, if you m—m—mean to sp—pp—split it into a th—thousand quarrelling f—factions? We d—duh—defend the you—yuh—unity of the M—Moravian realm, or all of this is in v—v—vain!’

As Kráľ Róbert stumbled and stammered his way laboriously through this speech, somehow the two young men who were fighting did pay attention and were appropriately chastened. They made their peace and went back to their tents, and spoke no more of the issue. Even so, it was clear to see that the Nositelia were far from happy about this treatment of their spiritual figurehead.

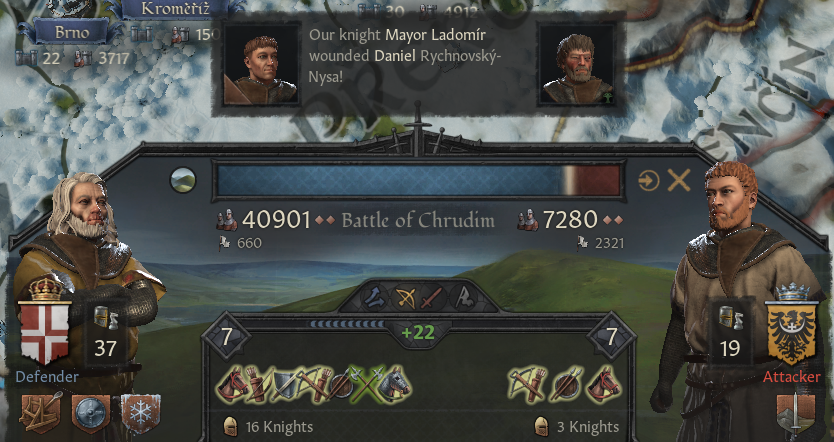

The engagements at Chrudim and Uničov were mostly one-sided operations in which the Nositelia were given the dirty work of mopping up. The glory went to the young king, naturally.

Much more major was the battle at Trenčín.

The Bohemian nobles quickly realised their error of placing a civilian like Záviš at the head of their army, and quickly replaced him with a mercenary captain of their own: a Luxembourger named Robrecht, who led the Brabantian Bedrijf van de Wolf. Robrecht was well-known as a commander who liked to take no prisoners on the battlefield—he attacked without mercy and left no one alive where possible. Alarmingly, the Luxembourgers in his company had been given, and had trained with, handgonnes. At Trenčín they would be using these weapons in battle against Moravians, on Moravian territory, for the first time.

At Trenčín the armies were fairly evenly matched. The Bohemians had joined up with the uprisen nobles from Podkarpatská, which swelled their numbers. There were sixteen družinniki on the loyalist side, and fifteen on the rebel side. The Moravian loyalists had a slight advantage of numbers, but this was counterbalanced by the larger number of zbrojnoši on the rebel side.

Still, Knieža Budivoj did what he knew best. Despite his rather arrogant demeanour, Róbert knew him to be a brilliant commander; and this was, after all, his home territory. He staked out the high, easily-defensible positions, and deployed the Nositelia mobile barricades and houfnice around them with an infantry line on either side for lateral protection. This made the main positions of the Moravian loyalists nigh impregnable. In the end, Robrecht was forced to fight his way through a gauntlet of houfnice fire, which decimated his troops as he fought across to the western side of the Moravian position. He thereupon fled to Čáslav, where again the Moravian loyalists caught him up.

Čáslav was also Moravian home territory, and here Kráľ Róbert took personal command. The Luxembourger was not as used to fighting in mountainous terrain, and with the few, exhausted and wounded troops he had left he didn’t stand much of a chance. Thus, the Moravian king made short work of the remnants of the Bedrijf van de Wolf, and took Robrecht prisoner.

The mines at Čáslav, however, could only produce so much ore, the furnaces could only smelt so much malm, and the mints could only strike so many silver coins. There wasn’t enough bullion in Robin’s war chest to continue as he had; mercenary troops like the Varangians and the Nositelia Viery being expensive to maintain. And so Robin appealed in writing to the young Ecumenical Patriarch Sabbas, who sent him back a cordial reply along with some six and a half pounds of fine gold to carry on the campaign.

In this campaign, Kráľ Róbert came to have a new appreciation for his maršal, whom he had disliked so much as a boy. Budivoj Mikulčický had stayed by him throughout this crisis, which in itself was commendable. But he had also obeyed several of the king’s orders he had disagreed with—in particular those relating to the Nositelia. And he continued to prove his worth on the battlefield, making excellent defensive use of the Nositelia’s armoured carts, mobile barricades and artillery to enhance fortifications wherever they were under threat. As a logistician, as a defender, and as a man who was clearly capable of handling winter campaigns, Róbert discovered a fresh well of respect for the older man.

Not everyone felt the same way, however.

‘We have these amazing new artillery pieces, the houfnice,’ complained Burgomaster Prelimír, ‘and all Mikulčický wants to do with them is hide away and hole up in defensive encampments! We need to take the fight to the enemy if we’re going to win this war! The offensive capabilities of the new weaponry are wasted on the likes of Mikulčický.’

Naturally, Budivoj took a much different view. Although when he was newly installed the Kráľ would have instinctively sided with Prelimír against Budivoj, now he took a rather more moderate tack.

‘B—Budivoj’s right: we do need to p—pp—protect val—valuable sites like Č—Čáslav,’ he told Prelimír. ‘We c—c—can’t risk the mines f—f—f—falling into rebel hands. O—On—On the other hand, though, I agree that we sh—should exp—p—periment a bit more with t—tuh—tactics in using these w—weapons. In p—pp—particular, let’s s—s—see how well they fuh—function as support for ch—chevauchée t—tactics on Bohemian t—t—territory itself.’

By this time the Greeks from Thessalia had arrived at the behest of the young Despot Ioustinianos. They had begun laying siege to key fortifications in central Bohemia, while the armies of Kráľ Róbert took up positions around Praha itself—and then Žatec, and then Sedlec. One by one each of these cities fell. It soon became clear that the houfnice, though nowhere near as powerful as the bombardy, still had their uses in siege warfare. However, the forces of the Kráľ weren’t the only ones on the move.

Drahomír 2. Rychnovský-Vyšehrad had gotten a second wind in him. He had gathered the nobles of Bohemia and Silesia together, and had waited for Siidalávlut Wizlaw and his band of Sámit from the north to join him at last in the contiguous territories of Moravia. They then moved straight against Olomouc.

The Bohemian noble rebels had siege equipment as well, fired by black powder, every bit as effective and destructive as that which the Moravian loyalists could bring to bear. The garrison fought the Bohemian noble rebels in the town and around Olomouc Castle for some months, but in the end the defenders of Olomouc could not hold out. The Sámi Siidalávlut was the first one inside the gates.

Never before had Olomouc itself fallen to an enemy siege. Wizlaw had done what countless enemies of Moravia across hundreds of years of history had been unable to do. He flew the black vane of the Sámit of Tuoppajärvi from the battlements of the town.

The frightened little blond toddler who clung to her wet-nurse on her way through the back corridors of the castle and out to a secret exit… Wizlaw seized. This young kinswoman of his, he hauled up over his shoulder and brought back out into the courtyard: a valuable hostage indeed. Kráľ Robin wouldn’t want to risk any harm coming to his only child! Two, however, could play at that game. Kráľ Robin already had, as prisoner in his own camp, Drahomír’s wife, the Kňažná Lesana. Once he heard that Helene had been taken prisoner, he made this known to the rebels. It was a standoff… though not an entirely balanced one. Wizlaw’s prisoner was, all things considered, far more valuable than Robin’s.

The final, decisive battle seemed to be swiftly upon them. The armies of the King marched back toward Moravia Proper, but then swung clear of attempting to take back Olomouc head-on. He turned instead to Velehrad, and to the newer town of Brno. There, by Brno, the loyalist armies met the armies of Drahomír once more.

The rebels were being led by a seasoned Sámi warrior, one of Wizlaw’s compatriots, whose name has unfortunately been lost to history. This Sámi warrior was much more formidable a commander than either Záviš or even Robrecht had been: he deployed his forces with great skill and forced even Budivoj onto a back footing. It looked briefly like the Moravian armies would be bested. But then the Greek armour-bearers of Thessalia appeared—and the tide of battle turned. The Thessalians brought not only men, but also ferocity and cunning upon the battlefield of which the heroes of whom Homer sung would be proud; and even the skilful Sámi whose might had kept the Moravians at bay was no match.

During the fighting, the forces of the king captured Boleslav, Drahomír’s brother. With both his brother and his wife in custody, the tide of the war was turning in the king’s favour, although he still didn’t have control of his own capital city.

The last thing Kráľ Robin did was to ride out himself, minus the Thessalians, northward toward Olomouc which was currently in rebel hands. He sought out, and found, Wizlaw Rychnovský-Žič and his band of Sámit; and he gave battle to them where they stood, in a copse on the banks of the Morava. When Wizlaw was taken prisoner, the first words that left Robin’s lips were:

‘Wh—wh—where is she?!’

Wizlaw glumly led the Kráľ to a nearby grotto, which served as a temporary fonsel. A voice came from inside.

‘Daddy! Daddy!’

‘Helene!’ Robin called out. He went forward into the cave and loosed his daughter’s restraints, then hugged her to him tight. She was none the worse for wear, though she was a bit shaken by her ordeal. Wizlaw treated his prisoners well as a matter of course—and besides, he had been hoping to keep her for ransom. Now the tables were turned, and Wizlaw was the prisoner rather than the king’s daughter.

With Helene freed and the brother of the Knieža as well as one of his chief vassals under guard, the rebellion could no longer be sustained. The Bohemians, Silesians and Sámit came to Olomouc to agree to a peace with the Kráľ, and Drahomír as well as Wizlaw was taken into the king’s keeping.

But the beginning of the end of the medieval era had already begun. New technologies and new tactics dominated the battlefield. Noble retinues no longer counted for as much; mercenary bands took their place… and would soon come to be replaced themselves with standing armies. Kráľ Robin himself, however, was but dimly aware of this. His concern was with making the most effective (and most humane) military decisions possible—grand thoughts of the changing nature of warfare and statecraft had yet to enter his teenage mind.

[1] Or, in another time and another universe, Hussites.

[2] This is a paraphrase of the historical Jan Hus’s written reply to Archbishop Zbynek’s enjoinders on some of his questionable teachings regarding the priesthood.

[3] In another time and in another universe, Jan Hus met a very different end at the Roman Catholic Council of Constance.

- 1