Wasn't aware of that. I do doubt that it ever was large scale, though.

Yes, you probably always have been able to grow some grapes here and there, but given it only now became viable, then I doubt it was viable back then. Doesn't mean you can't have had some local conditions allowing for a single vine or two.

Also, I'm skeptical about those strontium analysies honestly, after all the Egtved girl debacle and how a lot of very reasonable doubt was raised about that strontium analysis, but the researchers refused to listen.

(I'm not an expert, and it was years ago, so I can only remember the main points. But the main points were about how strontium levels have massively changed over time from farming, and that that also seems into neighbouring areas, etc. and hence you can't just compare modern day levels with old finds, like they did for the Egtved girl. Whether or not the criticism was valid I don't know, as I'm no expert, but I did follow the long articles on it and there was a lot of people unable to agree. And as mentioned the researchers behind the paper that started the discussion refused to really go into it when countered with counter arguments, so that does make me skeptical of this too.)

That makes sense.

Who knows, perhaps it was blue berries. American blueberries are quite different from European ones, from what I've been told, so could be that they weren't recognised as blueberries, but rather thought of as grapes.

Do American blueberries look like grapes?

I am eating a fruit salad with both American blue berries and native American red-purple grapes from a garden on the same spoon, and they look different enough to me in terms of color, size, texture, stem. Blueberries grow on bushes; native grapes grow on vines. Blueberries are blue, juicy, and sweet, wild native grapes are tart and have seeds and a tough skin.

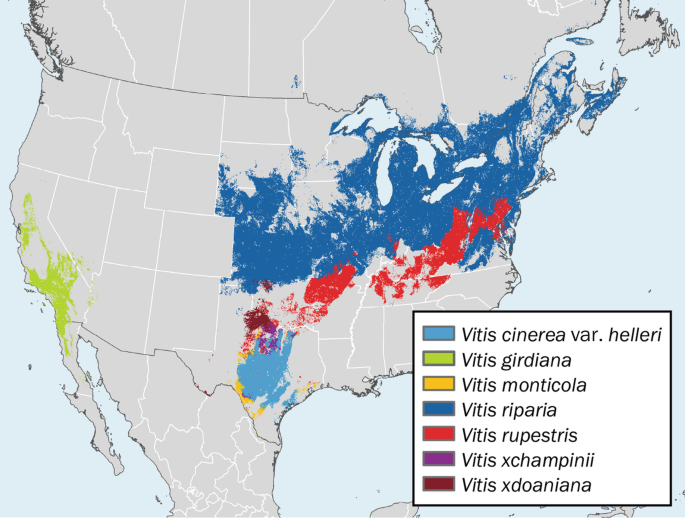

Wild American grapes like those on my spoon:

Unlike blueberries though, wild American grapes seem to have come in a variety of appearances, and when I look at photos of wild American grapes online where they are not close up, some of them remind me of blueberries in the photos.

But the issue is whether the 17th century EUROPEAN explorers could have looked at American blueberries and confused them with EUROPEAN grapes though. so whether

AMERICAN grapes look like American blueberries is less relevant.

I think that if Europeans put American grapes and American blueberries in their mouth, they would be able to tell the difference. American blueberries are pretty yummy IMO and work well in cakes and pies and oatmeal and pancakes, etc.

American wild grapes are relatively unpopular for straight eating and selling in grocery stores IMO because of how tart they are, how tough their skin is, the crunchiness of their seeds, etc. Actually, they really are OK to eat and not BAD, just not as good as Blueberries or as good as big sweet juicy yellow-green grapes. American wild grapes work well in winemaking.

Blueberry pancakes are popular in the US.

But anyway, actually

Yes, I can imagine that a European sailor from a city some place in England who is no specialist in world fruits could come to Canada and look at blueberries or some other kind of berry and think that he is looking at "grapes." Maybe the explorer even used "grapes" in some loose sense; Colonial Europeans had a special kind of cannon projectile that they called "grape shot" because it was made up of pieces.

We do have more than one colonial European source claiming to have seen "grapes" in Newfoundland though. The one English sailor whom I quoted from the 17th century saw them in eastern Newfoundland, whereas another modern scholar who I quoted said that they were were reported in western Newfoundland. So it seems to me that there were grapes there then, even though it's not totally proven.

On one hand, since grapes grow in Nova Scotia and can be artificially cultivated in Newfoundland, it seems realistic that 500-1000 years ago there were these kinds of grapes also in Newfoundland.

On the other hand, the Vikings talk about trawling away big cargoes of grapes, and they called the land "Vinland", as if it were Wine-land or Grape-land. If you saw tons of grapes in Nova Scotia and just scattered grapes in Newfoundland, you still might be more inclined to think of Nova Scotia as a "Grapeland." My point is that even if Grapes literally grew in both spots (Newfoundland and Nova Scotia), the grapes in Nova Scotia could still be more impressive and thus more likely to attract the Vikings as a "Vineland."

This kind of issue comes up with the discovery of Butternuts at L'Anse aux Meadows too, @Wagonlitz.

That is, we found butternuts at the Viking site in northern Newfoundland, so we can conclude that they certainly visited and camped in some place in Canada or the US with Butternuts, and this gives us 4 of the most northeastern locations:

A) A small area of the upper Miramichi River near Doaktown that flows into the St. Lawrence River

B) A large area of the St. John's River Valley, New Brunswick, that flows into the Bay of Fundy.

C) A big area of New England west of central Maine

D) A moderate area of Quebec, starting with the Quebec City area and going southwest along the St. Lawrence River Valley.

The patch below the W in "New Brunswick" in the map above is in the Doaktown area of the Miramichi River that flows into the St. Lawrence Gulf.

The rest is in the basin that flows into the Bay of Fundy.

On one hand, Option A) The Miramichi River Valley would be the quickest target option for the Vikings to get to. BUT the collection of butternuts there is much smaller than in Options B to D, which calls into major question whether the VIkings followed Option A to get the Butternuts. Plus, the Doaktown area of the Miramichi River is a narrow tributary and maybe 25 miles upriver from the main trunk and fork part of the Miramichi River where it would be easy for the Vikings to sail to.

The underlying issue in both cases (Newfoundland grapes and Miramichi butternuts vs. Nova Scotia Grapes and St. John butternuts) is whether the Vikings would be more likely to find and gather and focus on these fruits based on proximity to their proven location in L'Anse aux Meadows, or to find and gather them based on the giant quantity of the target resources farther away from Newfoundland.

Do you see what I mean?

Did I read that correctly in tha tit stated that the various grasses that are suspects were called wheat in Norwgian and Icelandic in 1910, or was it that Norwegian and Icelandic just called it wheat when publishing the sagas?

What country are you from, may I ask?

I think that you are talking about this quote:

The self-sown what was long itnerpreted as Indian Corn, but in recent years the theory advanced by Schubeler has been generally adopted, that the What (hveiti) seen by the Norsemen in Vinland was the American Wild Rice (Zisania).... there are, among the more than two hundred indigenous grasses which are found near the coast from New England northward, ten [footnote 2 for the Latin list] or more species which in superficial aspect are closely similar to the true Wheat (Triticum vulgare). Of these ten or more native grasses the species of Agropyron demand brief discussion, for by many authors they are united with Triticum, the true Wheat; and in modern works upon the Norwegian and Icelandic floras they bear the name Hvede.

NOTES ON THE PLANTS OF WINELAND THE GOOD, M. L. Fernald, Rhodora, Vol. 12, No. 134 (February, 1910), pp. 17-38 (22 pages)

The quote above says:

- 10 or more kinds of American wild grasses look somewhat like actual, true wheat (Latin name Triticum vulgare), but they are not actually true wheat.

- Many authors unite these 10+ American grasses with "true Wheat"

- In modern writing about Norwegian and Icelandic plants, these 10+ American wild grasses are called "Hvede". ("Hvede" is the Danish word for wheat.)

The picture above is true wheat, "Triticum vulgare."

So in conclusion, the 1910 book is not directly asserting that "Norwegian and Icelandic just called it wheat when publishing the sagas."

But the 1910 book is

suggesting as a possibility that the medieval Scandinavian writers "just called it wheat when publishing the sagas".

Pretty sure that Norse cosmology had the Earth be flat. With the various World's being in different parts of the entire "world body", with the sky being a sphere (Ymer's skull).

Afaik then the most common belief was that the various world's were inconcentric circles, with the innermost circle being Asgård, though I've also seen versions where the various parts are placed in different places around the World with the World Sea ground around, and a huge "bay" separating Asgård and Vanaheim and Midgård being at the bottom of the bay. That version also fits with how Udgård generally is said to be Østerled, i.e. in the East, and hence not as a circle around everything.

Though, as with everything in Norse mythology, then there's various contradictions between sources.

I've not seen any sayuing the World isn't flat, though, so I think it's safe to say they did think of the World as being flat.

Though, perhaps there are sources where they state it's not flat, but if so then I'm not aware of them.

OK. For purposes of the topic of the "One-Footer," what I read as one modern explanation of the Saga was that some medieval Europeans theorized that one kind of people living at the edge of the known world were "One-footers." In the modern Explanation, the Saga writer was either talking about a real literal event with a literal "one-footed" attacker, like on a crutch or peg-leg, or else the writer was adding the medieval theme of a "One-Footed" inhabitant of the world's edge into his Saga, without there being a literal "Uniped" person encountered.

Here is evidence for another reasonable explanation:

John of Marignolli (1338–1353) provides another explanation of these creatures. Quote from his travels from India:

[13]

The truth is that no such people do exist as nations, though there may be an individual monster here and there. Nor is there any people at all such as has been invented, who have but one foot which they use to shade themselves withal. But as all the Indians commonly go naked, they are in the habit of carrying a thing like a little tent-roof on a cane handle, which they open out at will as a protection against sun or rain. This they call a chatyr; I brought one to Florence with me. And this it is which the poets have converted into a foot.

— Giovanni de' Marignolli

en.wikipedia.org

That is, Europeans could have seen people in India or in Canada with a long stick and could have called the stick a single "leg" or "foot." So the original European narrators of such accounts could have referred to people with a long single leg, but they could have actually meant the stick by the "leg," instead of meaning that the person was missing one of humans' normal two legs below his waist.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/blueberries_annotated2-0ab902955b674c2a9af28d94d654cd06.jpg)