Yumtän appears to have quite a ruthless and pragmatic disposition. Impious as his actions are, he's certainly right that an incapable monarch is practically an invitation to plots and meddling for disloyal vassals and foreign rulers alike. He may yet have saved the kingdom, though at the cost of his own soul (if he values such things).

A Kingdom In the Clouds: A Ü-Tsang AAR

- Thread starter RossN

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Threadmarks

View all 43 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Part Thirty One: Tsenpo Purgyal Zhonnu 'the Holy' (1348 to 1367 AD) Part Thirty Two: Tsenpo Purgyal Selbar VI (1357 to 1361 AD) & the Regency of Prince Zhonnu (1361 to 1374 AD) Part Thirty Three: Tsenpo Purgyal Selbar VII 'the Lionheart' (1374 to 1396 AD) Part Thirty Four: Tsenpo Purgyal Selbar VII 'the Lionheart' (1374 to 1396 AD) (cont.) Appendix: The World in 1396 AD Part Thirty Five: Tsenpo Purgyal Selbar VIII 'the Great' (1396 to 1449 AD) Part Thirty Six: Tsenpo Purgyal Selbar VIII 'the Great' (1396 to 1449 AD) (cont.) Part Thirty Seven: Princess Purgyal Kelzang (1449 to 1452 AD)Just goes to show that one shouldn't stay longer than one is welcome - especially if one is on a throne!

Religious reformations are always tricky to get right I think, even in somewhat better known faiths.

Religious reformations are always tricky to get right I think, even in somewhat better known faiths.

Part Four: Gyalpo Purgyal Yumtän II ´the Festive´ (920 to 947 AD)

Gyalpo Purgyal Yumtän II ´the Festive´ in January 920 AD.

Part Four: Gyalpo Purgyal Yumtän II ´the Festive´ (920 to 947 AD)

The second Yumtän to rule over the kingdom of Ü-Tsang bore little resemblance to his predecessor and namesake. Few would call this monarch a staunch defender of family, at least after the death of his father, but the younger Yumtän lacked the strain of cruelty that had ran through to the marrow of the grandfather. As ambitious as he was the new Gyalpo was also the manner of man to weep openly over the death of a pampered pet cat [1]. This odd mix of traits made him a man of many of conflicting parts; paranoid and parsimonious with the truth yet diligent and patient as a ruler, a skilled and splendid soldier who delighted in intrigue. Yumtän's sobriquet 'the Festive', had originally been a cruel jibe at his facial features which were, to put it diplomatically, less than classically handsome [2]. Nevertheless in his later years the Gyalpo would indeed be known for his splendid revelries at court.

Yumtän of course had the great advantage that he had already ruled Ü-Tsang for half a decade when he was finally crowned. During his time as regent the then Crown Prince had married a distant cousin, Tsepong Chimey and produced a daughter, Princess Chödron who had the misfortune to inherit her father's craggy features. He had also formed the plans that he would enact once he actually came to the throne. It could be said that fear of losing this opportunities pushed him to, well, push Palkhorre into his eternal reward.

To understand the reign of Yumtän II we must understand his approach to foreigners. Other kings might have focused on conquest or faith. For Yumtän these were questions that had fairly easy answers. He was conventionally religious, neither cynic nor fanatic and had accepted the reforms of the Bön faith without attempting to interfere with the duties of his Chef Diviners. It is true that late in life Yumtän did identify with a personal divine patron devoting his personal prayers most often to the fearsome Damchen, the Worldly Protector but his imposing castle at Taktsé echoed to the rituals surrounding all the gods and spirits of the faith and even to other faiths at times. Even when the great Buddhist rebel Pushyavarman (of whom more shall be said later) was sentenced to death he met his end dangling at the end of a rope as a traitor rather the more gruesome punishments awaiting a heretic.

As for conquest Yumtän warred with the barbarians of Nagormo in 928, forcing their Ne (a sort of petty king) to swear fealty to the Gyalpo of Ü-Tsang, but this was more a matter of protection. Far too often had the Nagormons deliberately allowed the warlike savages of the distant plains through their lands in order to pillage the rich lands of Tibet. That Ne Tsongkha Junshi, known as 'Iron Fist' had taken the Daoist faith also alarmed the government of Ü-Tsang who wondered whether Junshi was but a pawn of the great empire to the East. The swift war that reduced Nagormo to vassalage ended Junshi's chances for making mischief... or so it was assumed at the time.

The foreigners that had most impact on Yumtän's plans can be divided into three unequal groups. First and most overtly dangerous were raiding barbarians - Jurchens, Tanguts and others. As they had for decades such men were drawn to wealth of the Silk Road like wasps to a fallen peach. This was the price of Tibetan prosperity; had the kingdom been poorer even the hardiest barbarian would never have attempted war on Ü-Tsang, hidden as it was behind the great natural walls of the mountains. The conquest of Nagomo helped for a time but in the end Yumtän was left with little option but to ride to battle, wielding the longsword of his father and a splendid new suit of shimmering lamellar armor, decorated with gold inlay. The Gyalpo vanquished the raiders more than once but always they, or others like them would return.

The Radhanites arrive in Ü-Tsang in January 925 AD.

The other two key groups of foreigners were very different. The first, the Jews, were entirely welcome and would add much to Ü-Tsang. The second group, the Chinese, would also be broadly positive for the kingdom but always there would be a streak of unease there, based on the knowledge of the power of the Middle Kingdom - and easily that power could flatten Ü-Tsang.

For at least three centuries groups of Jewish merchants had been operating trading routes across Asia reaching from the empire of the Franks to China. These merchants, known as the Radhanites, travelled east and west by several routes both overland and by sea and specialised in rare and priceless luxuries - spices, silks, slaves, furs and jewelry. Through their efforts a sword smithed in Constantinople might end up in a market in Chang'an or a necklace from Sind reach a souk in Baghdad. They were in a real sense the great merchant adventurers of the age, keeping the lifeblood of trade flowing.

Despite their wide ranging expeditions the Radhanites had been a rare presence in Tibet before the Tenth Century. Though part of the Silk Road ran through the Tibetan Plateau and Lhasa in particular bustled with the vendors and peddlers of a hundred different cities the Radhanites had skirted the forbidding deserts and mountains in favour of sailing for the ports of India or making north through the trackless plains that were in their way less dangerous. Even during the days of the Tibetan Empire the number of Radhanite merchants who visited the fringes of the empire had been few.

All that changed in 925 and perversely Ü-Tsang had both the marauding horse riding barbarians and China herself to thank. The curse of the raiding tribesmen has already been detailed and though it was an old pattern they grew especially disruptive in the late Ninth and early Tenth Centuries, turning once safe and practiced trade routes into lands of death and disaster. They were, unintentionally, aided in this chilling effect by the Chinese. Though China was, at least by the 920s undergoing a period of tranquility and prosperity many would call a 'Golden Age' the constant aggressive diplomacy of the Chinese emperors had unsettled much of central Asia and India. In these circumstances the Kingdom of Ü-Tsang appeared much more attractive, regardless of the inclement weather or terrain.

When Mordechai Binyamin arrived at Taktsé in January 925 he was thirty three years old, some six years younger than Yumtän. Mordechai was shy when speaking matters outside the world of trade and his weak chin hidden beneath a scraggle of a beard and face splatterdashed with ancient acne scars scarcely helped open him up in company. Nevertheless all who spoke to him for more than moments were struck by the young merchant's essential honesty and sense of justice, the bravery he had shown in the long trek that had taken him by ship, camel and foot from the Rhone to Tibet and above all by his shrewdness as a trader. As a merchant he had few equals and when he approached the Gyalpo Yumtän was so impressed he not only approved the request to set up a Jewish trading enclave in Lhasa he appointed Mordechai the court Gyner ('Minister of Finance' or 'Steward').

The Radhanite community in Tibet was not sizeable in real terms, numbering at absolute height a couple of hundred people in Lhasa proper with a smaller enclave in Taktsé centred around the most illustrious member of the family. Still despite their lack of numbers they made their presence felt in Ü-Tsang. New fashions and ways of thinking had brought in by this wave of fabulous exotics with their fanciful stories of distant kingdoms and they in turn became interwoven with the fabric of Tibetan life, with many including Mordechai himself eventually taking local women as wives.

Mordechai Binyamin, shortly before joining the court of Yumtän II.

In numerical terms the Chinese presence in Ü-Tsang was also relatively small, though they outnumbered the Radhanites. Years before in the reign of Palkhorre the Gyalpo's court had been graced by the presence of the skilled Daoist physician - others would say sorcerer - Qin Fangquing. He was long gone but Taktsé would see the presence of others during the era of Yumtän II, notably Captain Zhuan of Outlaws of the Marsh, a Han mercenary general of peasant birth, with an expansive appetites (and waist), a tactless tongue and a mind sharper than the finest longsword. This itinerant sellsword would never hold a court title in Tibet but he and his men would prove invaluable to the Gyalpo more than once.

The presence of Chinese mercenaries like Zhuan and his band of villains owed much to the strange situation in China. Though an in-depth history of the Middle Kingdom in the Ninth and Tenth Centuries lies beyond the scope of this chronicle, it is important to state the collapse of the Tang Dynasty and the rise of the Wei Dynasty had a profound impact on Central Asia and beyond.

The Wei Dynasty [3] changed the ruling family of China but the Weis were in most respect culturally and politically indistinguishable from the Tangs. The founder of the imperial line was the Emperor Zhang Taizhu (848 to 897) who had been involved in the rebellion that heralded the end of the old dynasty. Taizhu would spend most of his short reign combating the disastorous Jurchen invasion that had so crippled the Tangs. His son Dezong who ruled China from 897 to 924 overcame a murderous plague in the early days on the throne before China finally returned to a measure of stability. It would be under Dezong that the Wei Dysnasty would begin a dazzling period of expansion abroad and peace and prosperity at home, bolstered by the booty and tribute of foreign affairs.

In the first three decades of the Tenth Century the Wei armies marched nearly everywhere in the reach of China. Some states, like the Kingdom of Guge submitted voluntarily while others like the many proud kingdoms of India were forced to become tributaries at the point of a a spear. In some ways the hand of the Wei Dynasty was light on their subjects; foreign kings were allowed to keep their thrones and their powers subject only to a tribute to the Dragon Emperor and solemn undertakings to play fair with the merchants and bureaucrats of China.

For Yumtän, like his father Palkhorre before him, the Wei Empire represented a vast and menacing storm broiling in the eastern skies, threatening at any moment to break across Ü-Tsang. There were fringe benefits such as the arrival of the Radhanites and the services of men like Captain Zhuan whose temper and history made them illstarred in the Wei Court but the threat itself never diminished. Only with the passing of Dezong and the crowning of his son Ruizong in 924 did Yumtän breath a little easier. Ruizong was known to favour an open China rather than an aggressively expansionist one; indeed it was said that the Emperor, a man of quaint and simple views rather disdained tributaries. Ruizong was even, so the rumours said, intrigued by the Old Bön faith.

In June 943 Yumtän saw the opportunity to cement a peace with the Wei Empire without becoming a tributary to China. His old wife had passed and Yumtän decided to request the hand of a Chinese princess. The circumstances were fortuitous even aside from the benign nature of Ruizong. Yumtän had offered a disagreeable and illegitimate half brother as a eunuch to the Imperial court and though the boorish princeling would prove no more refined in Chang'an his blood, his faith and his exoticness charmed the Emperor. In turn the Son of Heaven sent his youngest daughter the Princess Que to Taktsé.

The arrival of Princess Que, July 943 AD.

Zhang Que's grace and wit did much to win over the many uneasy at Chinese influence in Ü-Tsang and in time she would produce a son and heir for Yumtän. However even that happy occassion would prove a mixed blessing as Yumtän's health declined in the 940s and the question of the succession began to raise its head...

Gylelmo ('queen') Que in July 943 AD, shortly after her marriage to Yumtän.

[1] Many legends about Sengemo the cat abounded during Yumtän's lifetime and after though the peasant belief that she was actually a demon in the form a small grey-white furred cat to whom the Gyalpo fed the souls of his enemies appears to have originated with his enemies.

[2] In a letter an Arabian traveler once noted that in certain lights Yumtän's face 'suggested his mother had intimate relations with a wild boar'.

[3] This Wei Dynasty was only distantly related to the Wei who ruled much of China during the Three Kingdoms period.

Last edited:

As before I have divided a lengthy reign into two parts so Yumtän's story will continue in the next chapter.

~~~~~~

DensleyBlair: Thanks! Yes, i knew Guge was a significant rival but the reformation caught me off guard. Still ever onwards!

darkhaze9: Thank you and yes I agree both about the sadness and the appropriate level of patience for a Crown Prince.

Specialist290: I think in his defence Yumtän would argue that the invasions of barbarians and the ever present threat of China required a strong hand at the tiller of the ship of state. Whether that excuses his actions is aother question...

Viden: Thank you, glad you like it!

Telcharinogrod: Thank you.

stnylan: That is true. It is an interesting angle to explore though, and an intriguing challenge!

~~~~~~

DensleyBlair: Thanks! Yes, i knew Guge was a significant rival but the reformation caught me off guard. Still ever onwards!

darkhaze9: Thank you and yes I agree both about the sadness and the appropriate level of patience for a Crown Prince.

Specialist290: I think in his defence Yumtän would argue that the invasions of barbarians and the ever present threat of China required a strong hand at the tiller of the ship of state. Whether that excuses his actions is aother question...

Viden: Thank you, glad you like it!

Telcharinogrod: Thank you.

stnylan: That is true. It is an interesting angle to explore though, and an intriguing challenge!

A remarkably fortuitous marriage alliance, or so it sounds like. I can quite easily imagine going from the Imperial Court to rougher lands on the roof of the world to be a bit of a big shock.

How fortuitous that a more sympathetic emperor rose up in China at just the right time!

A fascinating look at the cosmopolitan kingdom. I had no clue about the Ashkenazi history on the Silk Road, and the Chinese marriage is incredibly fortuitous. Yumtan’s open outlook to foreigners seems to have done his kingdom a number of great services.

Rather distantly related, I'd say, given the different surname. Alas, no return of Cao Cao's brilliant clan.[3] This Wei Dynasty was only distantly related to the Wei who ruled much of China during the Three Kingdoms period.

Love the addition of the Radhanites, and it looks like you struck gold with Mordechai... though it does also seem as though ugliness runs deep in Ü-Tsang.

Count me as another who is rather fascinated by the Radhanites. I'll have to do a bit more reading on them -- they seem like an incredible bunch of people, to travel so far and wide in a world that still travels by horse and sail at the very fastest.

Marrying an Imperial princess is certainly quite the diplomatic coup for Yumtän -- apparent legitimation of his own house's pretenses of Imperial glory to other Tibetans, as well as a direct link to the strongest power in that corner of the known world. Valuable assets indeed for any ruler, assuming of course that the Wei manage to maintain the Mandate of Heaven themselves...

Marrying an Imperial princess is certainly quite the diplomatic coup for Yumtän -- apparent legitimation of his own house's pretenses of Imperial glory to other Tibetans, as well as a direct link to the strongest power in that corner of the known world. Valuable assets indeed for any ruler, assuming of course that the Wei manage to maintain the Mandate of Heaven themselves...

Last edited:

Just came across this the other day and have very much enjoyed it so far. It's a very interesting part of the world to learn about, and I'm looking forward to the journey!

Part Five: Gyalpo Purgyal Yumtän II ´the Festive´ (920 to 947 AD) (cont.)

The 'Yarlungi Revolt' or 'Ü-Tsang Civil War' of 922 AD.

Part Five: Gyalpo Purgyal Yumtän II ´the Festive´ (920 to 947 AD) (cont.)

In 867 the old Tibetan Empire had been shattered into fifteen different states. Eighty years later and that total stood at just two: Guge and Ü-Tsang. By any standards it was an impressive achievement, but such consolidation had not been without cost.

Though outright conquest had played a part much of the expansion of both surviving kingdoms had been through diplomacy, sometimes diplomacy wrapped around a sword but a delicate dance of force and persuasion nonetheless. This had resulted in overmighty local nobles like the Ne of Nagormo or the Thupo of Nagchu who retained much of their wealth and power even as they genuflected to the court at Taktsé. Still more great barons were created by the practice of inheritance among the Tibet royals where every legitimate child of the monarch gained some part of the parent's estate as an inheritance. The end result was a land full of aristocrats who knew in the marrow of their bones that wealth or blood or both should at a minimum secure them a place on the royal council - and there were only so many Great Ministries available. Palkhorre and, especially, the second Yumtän tended to promote on merit rather than grandeur meaning that many of those unkindly termed the 'overbred and underbrained' by the scathingly honest Mordechai Binyamin were left cooling their heels.

In November 922 this seething cauldron would bubble over into outright civil war. The immediate cause drew from seeds planted during Yumtän's time as Regent. The then Crown Prince had ruled from the fortress of Gyangzê while his father remained in the official capital of Taktsé, leaving the great nobles the choice between paying court to ailing yet still crowned Palkhorre or his son. Many had chosen the former course only to find themselves outside the charmed circle once Palkhorre died and Yumtän reigned in name as well as fact. The problem lay in Yumtän's sharp eye for intrigue and the paranoia that always twitched its tail in his fertile mind. Yumtän was not a man who trusted easily and his hazy relationship with the truth and the distasteful business that saw him take the throne early lowered this ability still further. Those who did break through this barrier tended to be boon companions and it is no coincidence that many of them like the great Marshal Songsten or later Mordechi the Radhanite were fundamentally outsiders - commoners or foreigners who owed their power both to their own talents and to Yumtän's favour rather than a pre-existing powerbase.

Ironically the man who led the rebellion of 922 had perhaps the least reason of any of Yumtän's subjects to betray him. Purgyal Wangdu, the young Thupo of Lhasa known as 'the Monster' was the Gyner of Ü-Tsang. While his blood was very blue - he was the grandson of the first Yumtän and the current monarch's cousin - Wangdu was genuinely talented with money as was to be expected from the man who was overlord of the richest city in Tibet. Lhasa's days as the old imperial capital might have faded from memory but she was still the great stop on the Silk Road and grander than grim Taktsé, a fortress hacked from mountain stone.

One issue Wangdu did possess was a ferocious temper. Dark legends swirled of a servant he had flayed alive for a minor faux pas regarding the serving of meals, with the already gruesome details growing in each retelling as it took on new life in the horribly fascinating murk of the rumour mill. Was it true that the Monster of Lhasa had the girl's skin refashioned by artful tanners into a fine pair of boots? Wangdu did himself so no favours in hindering such lurid whispers by his aristocratic aloofness, which itself was perhaps a manifestation of shyness. In any case a mercurial combination of Wangdu's thin skin and Yumtän's innate distrust proved fatal to any close connection the two might have shared. Wangdu would fertile ground with others who resented the Gyalpo and his creed of greater power for the Ministers proved seductive to many aristocrats.

The Monster of Lhasa hands the Gyalpo his ultimatum, 30 November 922 AD.

When Wangdu found his demands refused he unfurled his standard of rebellion. Of the nobles who flocked to his aid the greatest was Thupo Miowche Rabten II of Nagchu, known as 'the Noble'. Rabten the Noble was the grandson and heir of Palkhorre's old friend and if Wangdu was the leader and brains of the rebels the Thupo of Nagchu was the truly popular one. Between them the two great nobles managed to sway almost half of Ü-Tsang to their side. The rebels were known as the 'Yarlungi rebels', named after the great river whose fertile basin made life on the Tibetan plateau possible.

So great were the rebels that Yumtän was forced to turn to mercenaries to bolster the Royalist levies, relying on the vast resources of silver and gold left to the treasury by by his father and grandfather. Fortunately the wily Chinese sellsword Captain Zhuan was at hand, as was an element that was even more valuable than two thousand battle hardened Han soldiers: luck. The two great enemies of the Gyalpo would be struck down by nemesis far from the battlefield.

Rabten the Noble would be the first to go. Nagchu was a wealthy province and Rabten had always possessed a taste for imported luxuries, a regular feature of his famous gatherings. Even when the war broke out his health was not the best and the terrors of the campaign trail kept him away from active generalship. Alas he reckoned without the terrors of his own castle and gout would hobble him late in 923. The same disease (or rather complications from it) would carry him away from this life on 9 January 924. His successor was his eight year old daughter Miwoche Tricham.

That left Wangdu the Monster. Never a superlative warrior his rank still required him to be present as leader at the great battles of the war culminating at the key Battle of Jokhang near Lhasa on 30 January 924. The clash was a bitter one, fought in poor weather so close to walls of Lhasa that errant fire arrows blown of course landed among the buildings of the city itself, firing several stables and other buildings. In the lack of light with dusk chasing dawns tail neither side had much room for tactical brilliance but eventually the Royalists and Captain Zhuan's Han infantry broke the enemy. Wangdu managed to retreat from the field with most of his men but at the cost of his pride - and his capital for the Royalists quickly besieged and then took Lhasa.

Even so the rebels might have regrouped at this point - Yumtän had an advantage in numbers now but hardly an invincible advantage - but for Wangdu's sudden illness. The night after the battle the Thupo of Lhasa and a few of his retainers sought refuge in a mountain village, a tiny nameless place of goatherds who looked on every foreigner as a sorcerer or demon and who fled in terror at the influx of a score of soldiers in lamellar armor, many still covered in blood and visibly distressed. Exactly what happened next is unclear - Wangdu may have been poisoned by a tainted well abandoned by the villagers, he may have been cursed by the local wisewoman or he may simply have contracted a fever he was too exhausted to fight off but his health never recovered. Within days he was too weak to take effective command of the army, and when this weakness and pallor was accompanied by episodes of frenzy even his closest allies became afraid to aid him - Wangdu had a murderous temper even at his best. He died frothing at the mouth on 3 May 924, aged only twenty three. With no children his title passed to his twelve year old niece Purgyal Khrimalod.

The war continued until September but with the rebels led by two children the outcome was never in doubt and really the entire point of the war had been rendered moot. After capturing several key towns Yumtän accepted the enemy surrender and allowed Khrimalod and Tricham their freedom and the retention of their titles. The Gyalpo did not hold either girl responsible for the ambitions of the predecessors. He did however require them to pay ransoms for themselves. Civil wars were costly endeavors after all.

The defeat of the great barons in the war, added to the eerie circumstances of their deaths bought Yumtän some years of calm during which he could turn to other matters. However the central problem still remained. The Kingdom of Ü-Tsang remained a patchwork of lands held by powerful nobles. The conquest of Nagormo in 930 added yet another to throng in Ne Tsongkha Junshi, known as 'Iron Fist'. The Ne of Nagormo was only a few years removed from being a great barbarian chieftain and as a Taoist in a land overwhelmingly dominated by Bön was doubly an outsider. However it was this very quality that would make him an unlikely ally in the schemes of Camakhura Thrisong, the Chieftainess of Bumthang. Thrisong was an arch-conservative member of the 'Old Bön' movement, and though her ambitions were not directly religiously motivated they did perhaps add to a feeling of being outside Yumtän's charmed circle.

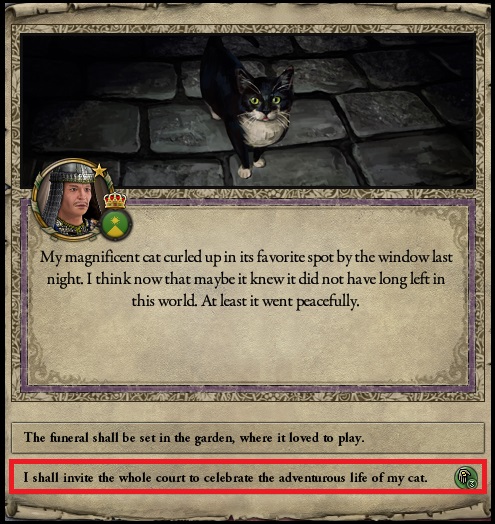

The death of Sengemo, 31 May 933 AD.

Sengemo - the beloved 'Little Lioness' that Yumtän treasured more than anything in his treasury, more whispered some, than his many daughters, died at the end of May 933. The Gyalpo, clad in mourning attire ordered the great courtiers to the Royal Gardens for a celebration of the cat's life. As the ceremony took place the plotters found time to speak to each other as the priestess spoke to the gods and a desolate Yumtän's thoughts lay far away, his razor sharp paranoia dulled.

The third recruit was the Gyalpo's own half-sister. Princess Purgyal Ngawang of Xigazê was only twenty two, much younger than Thrisong or Junshi but she was of formidable character, brave, diplomatic and shrewd. Yumtän himself had more than once considered appointing the princess as his Lönchen but decided against it on account of her youth. Still, she was determined to reach what she considered her rightful rank.

Within weeks Yumtän was faced with a second demand for increased council powers and when he refused a second civil war. This time however there would be no eerie yet natural deaths and the Gyalpo was forced to win the war in the field. Fortunately for Yumtän the plotters were better at coordinating the moment to strike than their actual armies and the Royalists managed to defeat the enemy in piecemeal fashion. The Ne of Nagormo in the far north of Ü-Tsang proved the most difficult to bring to heel but by September 935 even he was forced to surrender.

For Camakhura Thrisong, judged the grand architect of the revolt there could be no clemency and she went to the gallows on 12 September 935. Ne Tsongkha Junshi on the other hand would spared death, if only because the barbarian's personal fiefdom was too powerful to allowed to fall to his son. The Ne of Nagormo would instead rot in the dungeons of Taktsé. That left Yumtän's half-sister and a problem. Whether it was because Yumtän had grown sentimental in late middle age or whether it was because the princess was popular she too would avoid death. However she could be permitted to leave the royal capital for the rest of her life. It seemed a safe compromise but within less than two years Princess Purgyal Ngawang of Xigazê would prove herself troublesome even in captivity. On 7 April 937 Thumo Miwoche Tricham of Nagchu, the daughter of Rabten the Noble rebelled with the intention of putting Ngawang on the throne.

For the third time in his reign Yumtän would face a major rebellion. This time his response was utterly ruthless. First to die was Tricham's general Khadrobum, captured in battle in July 938 and hung immediately after as a traitor. The Thumo of Nagchu would follow her follower in May 939, beheaded after her own capture and the end of the war.

The extraordinary turmoil of the great barons and the fact that his first wife had produced only daughters forced Yumtän to consider radical steps once Zhang Que bore him a son in March 945 [1]. As the law stood daughters and sons inherited equally, meaning the throne would pass to his eldest daughter Princess Chödron while the estate would be divided among his other children. Yumtän, afraid that to do so would leave the next monarch crippled both by the congenitally disloyal great barons and by her own siblings declared that henceforth female children would inherit only in the absence of males. In other words everything would go to Young Yumtän.

Exhausted and bedridden with gout Yumtän II passed away on 12 August 947 at the age of sixty two. His plan had worked to a point with the entire royal estate passing to Yumtän III. Unfortunately the new monarch was a little over two years old...

The Kingdom of Ü-Tsang in August 947 AD.

Footnotes:

[1] Another Yumtän, inevitably known as Young Yumtän.

Last edited:

When I posted the update last week it had been over a week since I had played the game (with a holiday in Porto falling in between) and I had forgotten quite how turbulent the domestic sphere had been for Yumtän II. Three major rebellions by his nobility and a Buddhist uprising in his later years that I didn't quite have room to detail!

It was almost like writing The Queen of Cities all over again...

~~~~~

stnylan: In fairness Tenth Century Tibet is fairly civilised. I suppose the equivalent might be a Byzantine princess journeying to a Northern European court - definite culture shock and perhaps less sophisticated but at least a recognisable form of society!

darkhaze9: Well, yeah. China was extremely expansionist with essentially the entire subcontinent as their Protectorate at one point! :O

DensleyBlair: Yes, they are an absently fascinating people though unfortunately our knowledge of them is limited. I quite agree it added a cosmopolitan air to the Gyalpo's court!

Andrzej I: Yes the family name thing puzzled me but the game does call them the Wei Dynasty. and as I said above the Radhanites were fascinating and very welcome!

Specialist290: The Wei Dynasty are doing very well. Even under the current non-expansionist monarch they are enjoying a Golden Age. Still you are right they might not hold on for the long term!

Riotkiller: Thank you! So glad you are enjoying this and hope you continue to do so!

It was almost like writing The Queen of Cities all over again...

~~~~~

stnylan: In fairness Tenth Century Tibet is fairly civilised. I suppose the equivalent might be a Byzantine princess journeying to a Northern European court - definite culture shock and perhaps less sophisticated but at least a recognisable form of society!

darkhaze9: Well, yeah. China was extremely expansionist with essentially the entire subcontinent as their Protectorate at one point! :O

DensleyBlair: Yes, they are an absently fascinating people though unfortunately our knowledge of them is limited. I quite agree it added a cosmopolitan air to the Gyalpo's court!

Andrzej I: Yes the family name thing puzzled me but the game does call them the Wei Dynasty. and as I said above the Radhanites were fascinating and very welcome!

Specialist290: The Wei Dynasty are doing very well. Even under the current non-expansionist monarch they are enjoying a Golden Age. Still you are right they might not hold on for the long term!

Riotkiller: Thank you! So glad you are enjoying this and hope you continue to do so!

Last edited:

Hmm… not the best time for a long regency, it would seem. Hope the barons don’t feel too tempted to take advantage of the young king.

Nothing too puzzling about it! Dynasties were, typically, named after a title the founder held (in Cao Cao's case, he was the Duke of Wei (魏公)), based often upon the old Spring and Autumn states of yore. As such, the founder of this Wei dynasty likely held lands around what is now Shanxi. Possibly in some parts of Henan or Hebei. Given its success here, it'll likely be known as the Wei dynasty, but perhaps also as "Zhang Wei" if clarification were needed (so as to not be confused with "Cao Wei" or "Yuan Wei", the latter being one of the Northern Dynasties, perhaps better known as "Northern Wei" or "Later Wei").Andrzej I: Yes the family name thing puzzled me but the game does call them the Wei Dynasty. and as I said above the Radhanites were fascinating and very welcome!

Last edited:

It appears as though Yumtän's reign has been anything but festive for the man himself, given the constant churn of plots and rebellions; sort of makes his claims of his proactive succession being necessary for the realm's stability ring a little hollow in retrospect.

And now because of his efforts, the Younger Yumtän is left with an entire kingdom at a tender age, and at the mercy of snubbed nobles out to repay the sins of the father on the one hand and power-craving courtiers looking for a convenient pawn on the other. Karma has a funny way of working out sometimes...

And now because of his efforts, the Younger Yumtän is left with an entire kingdom at a tender age, and at the mercy of snubbed nobles out to repay the sins of the father on the one hand and power-craving courtiers looking for a convenient pawn on the other. Karma has a funny way of working out sometimes...

Well, all this plotting doubtless helped to keep him on his toes if nothing else.

But I suppose one could look at it all as being along the lines of there being a reason Tibet fell apart, and only time will tell if U-Tsang can avoid that fate.

But I suppose one could look at it all as being along the lines of there being a reason Tibet fell apart, and only time will tell if U-Tsang can avoid that fate.

So, a two year old half-foreigner baby surrounded by scorned half-sisters with claims on the throne. What could possible go wrong?

Threadmarks

View all 43 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode