Chapter IV: New Parties, Old Enemies

New elections, eagerly sought by the right and by much of the left, were part of President Alcalá Zamora's continuing effort to “center the Republic” . He was in many ways sorely disappointed in the new regime and its constitution. His concept of the Republic was a liberal democracy with equal rights for all, a democratic system that would deal with pressing social problems, but envisioned the Republic above all as a state based on an objective rule of law not subject to arbitrary political whims (a pity he did not apply this rule to his own machiavelic movements). His attempt to build a strong center party, however, failed again. The small center groups, led by Miguel Maura, Melquiades Álvarez, Alcalá Zamora himself, and a few others, held few seats and sometimes refused to cooperate among themselves. Similarly, the most moderate and responsible of the Socialist leaders, Julián Besteiro, had been marginalized by Largo Caballero from the active party leadership. Spain's future was left to the whims of the Radical factions in both sides.

The electoral campaign was somehow free of violence, in spite of the usual incidents when it refers to the Spain of the 1930s. The strong language used by both Socialists and the CEDA did not help to avoid that violence, though. The Socialists invoked revolution, while CEDA leaders spoke of the need for “a strong state” and “a totalitarian policy.” There were outbursts of anticlerical violence and a number of church burnings, as was de rigueur under the Republic, and the paramilitary wings of the PSOE and the CEDA clashed in the streets, from time to time, but the Guardia de Asalto managed to keep them at bay with equal ruthless.

In this mess, the new part created by Manuel Azaña, Izquierda Republicana (Republican left) found no time to create itself a space as a moderate leftist republican movement. Azaña did not trust the Socialists. He was aware of their hatred towards the Republic, which, for them, was no better than the monarchist regime. Alàs, he hardly knew that he was to become a key piece in the final destruction of the Spanish Republic.

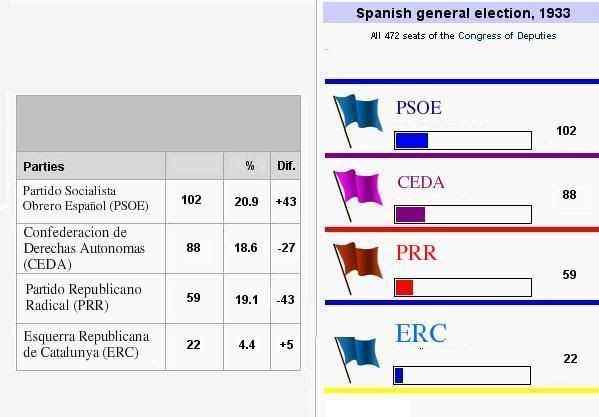

Election day was generally calm. The conditions of balloting were generally the freest and fairest in Spanish history to that date. By the time the segunda vuelta, or second round, was over, the big winners were the Socialist. The PSOE, capitalizing on the popular vote, emerged as the largest single party, with 102 deputies. The CEDA, with the support of the lower-middle-class Catholic vote, were the proportionately most overrepresented party, with 88 seats. The biggest loser was Lerroux, as the PRR was nearly wiped out and reduced to 59 deputies.

Azaña (right) and General Francisco Franco (left).

As events would prove, history was to have a

common fate for them, even if they were to fight

in oppposite sides.

Clearly, there had been some shift of opinion in the center and center-right, together with a much more intense mobilization of the leftist vote; yet the actual change of opinion was less than the drastically altered composition of parliament made it appear. The overall abstention rate was 32 percent, not far from the average of the preceding Republican elections. This was well above the west European norm, but not necessarily surprising for a country still with 25 percent adult illiteracy and a large anarchosyndicalist movement that promoted abstention.

Altogether, the Socialists had drawn more than 2.5 million votes, the moderate right more than 2 million, the CEDA nearly 1.7 million and the Radical Republicans fewer than 1.2 million. The extreme right garnered nearly 800,000 votes, the Communists and other parties of the extreme left less than 200,000. The potentially most dangerous feature of the new Cortes was the virtual annhilation of the democratic center, which, among all broad sectors, had drawn a plurality of votes.

The elections had generally been fair, though subsequently the results were impugned in several provinces, especially in Andalusia. There fraud was committed by both left and right, though perhaps most marked in the case of rightist fraud in Granada province, where the left had behaved equally badly in 1931. The defeated right reacted with rage and was much less disposed than in 1931 to accept temporary defeat. Their initial response was not to prepare to act as a loyal opposition but to attempt to gain cancellation of the electoral results. In the end, they abandoned this idea and sought to subvert the legal order through political manipulation.

The ball was now on the Socialist court.

PD: Minor parties: Comunión Tradicionalista (the Carlists) 15 seats, 1.9 % votes, -5 seats; Lliga Regionalista (a Catalan center party) 12 seats, 2.5% votes, -12 seats; PNV (Basque Nationalist Party) 12 seats, 1.9 % votes, +1; Falange Española 3 seats, 3,0 % votes, +2 seats; Partido Agrario 1 seat, 2.1% votes, -29 seats.