A Republic on the River Main - A Frankfurt DW AAR

- Thread starter unmerged(275742)

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Preface:

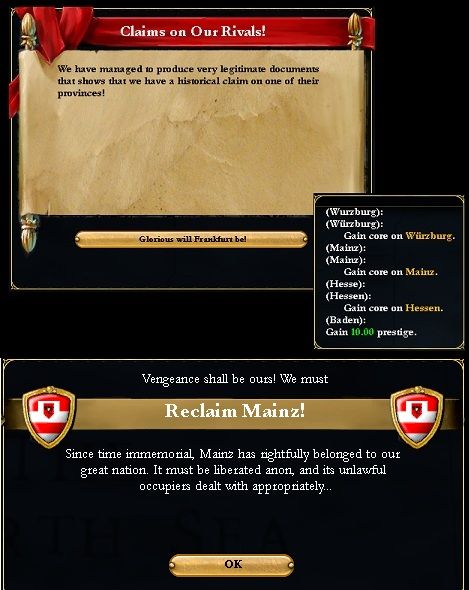

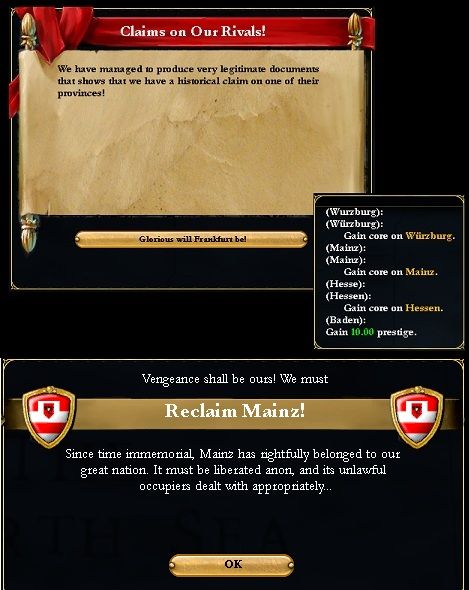

Well I took a big halt with this AAR mainly due to my lack of experience as an AAR writaar. The test run of Frankfurt I had done before starting this AAR gave me Boundary Dispute + Claims On Our Rivals 12 years into the game and I was ruling most of Germany (cored) by 1585ish. However THIS game waited until 1538 to give me my first core :laugh:. I am fully aware of the multitude of other ways to acquire casus bellis and expand without waiting for cores, but it's how I personally enjoy playing my EU3 games. The problem is this doesn't translate easily into the story type of AAR's I like presenting. I wasn't about to make people read through 130 years worth of "and then I sent a merchant here.. and then here... and where the hell is that claim already?", but I wasn't sure how to approach it so I left it. Well I've decided to give the AAR thing another shot, and so the format will change a little bit. When there are long stretches of peace (hopefully not many after the initial one) the AAR will be more like a timeline with footnotes and when Frankfurt's major wars occur, when the real action occurs, they will be their own chapter presented with the story AAR approach. The saved file I picked back up was actually a few months earlier than the final content of the previous chapter so there are slight differences.

1412-1538

1415: Friedrich Gohler 7/6/7 becomes the new syndic.

1416: Frankfurt finally established full trade with Novgorod. The army was raised from 3,000 infantry to 4,000 to outnumber Wurzburg and then rose to a further 6,000 infantry to protect against Hesse.

1417: Franfurt begins to establish trade in Andalucia and Lisboa, conquering the Iberian markets.

1419: Markus Schmitt 4/4/9 becomes the new syndic.

1423: Frankfurt begins to enlarge the army to counter the Hessian threat of 5000inf/2000cav.

1426: Frankfurt's army sits at a total of 7000inf/2000cav. Bohemia annexes Brandenburg.

1441: Konstantin Volz 3/3/6 becomes the new syndic.

1444: Markus Gohler 5/3/3 becomes the new syndic.

The First Austro-Bohemian War (1449-1450): Austria was long the Holy Roman Emperor, but it was not an easily kept crown, Bohemia's conquest of Brandenburg had created two formidable Central European states who both wanted the same crown. The Austro-Bohemian war fell heavily in favor of Austria and even a late entrance by Poland was powerless to stop the Austrian army. Strangely enough Austria settled the war for nothing more than Ersekujvar and the release of Silesia.

1448: Karl Theodor Ickstadt 5/3/6 becomes the new syndic.

1452: Thomas Fust 3/6/5 becomes the new syndic.

1456: Stephan Storck 6/7/5 becomes the new syndic.

The Second Austro-Bohemian War (1459-1460): A new war erupts between Austria and Bohemia with Austria once again overrunning Bohemia rapidly.

1460: Sigmund Dorrenbecher 6/3/5 becomes the new syndic.

1461: For all of Austria's military success, diplomatically Austria failed to retain the crown of the Holy Roman Emperor and Jiri I of Bohemia became the new Holy Roman Emperor after over 50 years of Habsburg dominance.

1462: England annexes Scotland.

1464: Michael Alfter 3/3/8 becomes the new syndic.

1473: The Hessian army sitting at 5000inf/4000cav prompts the enlargement of the Frankfurtian army to 9000inf/3000cav.

The Bohemian-Polish War and the French-Burgundian War (1482-1488): Two major wars broke out almost simultaneously. France had successfully consolidated most of France and was pushing hard into a large Burgundy. In the east, Bohemia waged a war of opportunity against a Poland that was too busy pushing into the Golden Horde's Ukranian possessions to fight back. Spain consolidated on the Iberian peninsula and most of North Africa was split between Spain and Portugal.

1488: Joachim Volz 7/6/8 becomes the new syndic.

1489: The University of Frankfurt is founded. France concludes a minor war against Spain that gives them dominion over most of the Pyrenees Mountains.

1490: Frankfurt traders, nearing a century of economic dominance over European markets, began to establish monopolies.

1492: The long awaited war re-erupts between Austria and Bohemia. Bohemia catches Austria off-guard and captures Vienna initially but Austrian territory is re-captured and the war ultimately ends in a bloody draw.

The Wars of 1500 (1500-1504): At the turn of the century Europe is ablaze with war. Portugal and England war with Spain for North Africa and Spanish Galicia. France fights a tough war against Milan,the still-relevant Burgundy and her assortment of Dutch vassals, and an aggressive Venice eager to take French lands in South Italy. Austria and Bohemia-Poland predictably engage in another disastrous bloodbath against one another. None of these wars are won decisively and they set up the remainder of the century for a seemingly never-ending chain of wars over much of the territory originally sought in The Wars of 1500.

1509: Former allies, England and Portugal, go to war with each other. England had used the previous Iberian Wars to conquer territoy for herself while doing very little to restore the Portuguese lands the Spanish had taken long ago. The parasitic nature of the alliance led to inevitable war, which the English easily won.

1511: Burgundy's outward appearance of strength finally gives way to her unsolvable internal problems and the state all but dissolves.

1512: The old Teutonic Order transforms into the state of "Prussia". Eastern Europe had spent most of the past century in utter chaos but from it grew the three powerful states of Prussia, Poland, and Muscovy who had managed to conquer and consolidate sizable territories.

The English War for Austrian Italy (1512-1516): Over the decades Austria had managed to peacefully, through marriage, gain strong North Italian holdings. England, alternatively, had militarily developed a strong hold on the Italian peninsula. It didn't take very long for England's warmongering to spill over from North Africa and Iberia, and into Italy in a full-fledged war with her ally Tuscany against Austria. Although England and Tuscany captured Austria's Italian holdings, a war of opportunity had developed and suddenly England found herself once again allied with Portugal trying to hold off a strong Spain on the mainland while taking her African territories. These wars were a major investment by England and they were ultimately about to fail. France had decided it was time to intervene. England ended up losing what was left of their old French holdings, half of their Italian territory, and their vassal Tuscany. Looking to boost their much-battered prestige domestically, England formally re-branded their government as "Great Britain".

1519: France further battered down the rump-state of Burgundy through war.

1524: An ambitious Eugen Barth 3/7/9 becomes the new syndic, overthrowing the 36 year dominance of Joachim Volz. Little did he know his time in office would oversee the most important time in Frankfurt's history.

1538:

Well I took a big halt with this AAR mainly due to my lack of experience as an AAR writaar. The test run of Frankfurt I had done before starting this AAR gave me Boundary Dispute + Claims On Our Rivals 12 years into the game and I was ruling most of Germany (cored) by 1585ish. However THIS game waited until 1538 to give me my first core :laugh:. I am fully aware of the multitude of other ways to acquire casus bellis and expand without waiting for cores, but it's how I personally enjoy playing my EU3 games. The problem is this doesn't translate easily into the story type of AAR's I like presenting. I wasn't about to make people read through 130 years worth of "and then I sent a merchant here.. and then here... and where the hell is that claim already?", but I wasn't sure how to approach it so I left it. Well I've decided to give the AAR thing another shot, and so the format will change a little bit. When there are long stretches of peace (hopefully not many after the initial one) the AAR will be more like a timeline with footnotes and when Frankfurt's major wars occur, when the real action occurs, they will be their own chapter presented with the story AAR approach. The saved file I picked back up was actually a few months earlier than the final content of the previous chapter so there are slight differences.

1412-1538

1415: Friedrich Gohler 7/6/7 becomes the new syndic.

1416: Frankfurt finally established full trade with Novgorod. The army was raised from 3,000 infantry to 4,000 to outnumber Wurzburg and then rose to a further 6,000 infantry to protect against Hesse.

1417: Franfurt begins to establish trade in Andalucia and Lisboa, conquering the Iberian markets.

1419: Markus Schmitt 4/4/9 becomes the new syndic.

1423: Frankfurt begins to enlarge the army to counter the Hessian threat of 5000inf/2000cav.

1426: Frankfurt's army sits at a total of 7000inf/2000cav. Bohemia annexes Brandenburg.

1441: Konstantin Volz 3/3/6 becomes the new syndic.

1444: Markus Gohler 5/3/3 becomes the new syndic.

The First Austro-Bohemian War (1449-1450): Austria was long the Holy Roman Emperor, but it was not an easily kept crown, Bohemia's conquest of Brandenburg had created two formidable Central European states who both wanted the same crown. The Austro-Bohemian war fell heavily in favor of Austria and even a late entrance by Poland was powerless to stop the Austrian army. Strangely enough Austria settled the war for nothing more than Ersekujvar and the release of Silesia.

1448: Karl Theodor Ickstadt 5/3/6 becomes the new syndic.

1452: Thomas Fust 3/6/5 becomes the new syndic.

1456: Stephan Storck 6/7/5 becomes the new syndic.

The Second Austro-Bohemian War (1459-1460): A new war erupts between Austria and Bohemia with Austria once again overrunning Bohemia rapidly.

1460: Sigmund Dorrenbecher 6/3/5 becomes the new syndic.

1461: For all of Austria's military success, diplomatically Austria failed to retain the crown of the Holy Roman Emperor and Jiri I of Bohemia became the new Holy Roman Emperor after over 50 years of Habsburg dominance.

1462: England annexes Scotland.

1464: Michael Alfter 3/3/8 becomes the new syndic.

1473: The Hessian army sitting at 5000inf/4000cav prompts the enlargement of the Frankfurtian army to 9000inf/3000cav.

The Bohemian-Polish War and the French-Burgundian War (1482-1488): Two major wars broke out almost simultaneously. France had successfully consolidated most of France and was pushing hard into a large Burgundy. In the east, Bohemia waged a war of opportunity against a Poland that was too busy pushing into the Golden Horde's Ukranian possessions to fight back. Spain consolidated on the Iberian peninsula and most of North Africa was split between Spain and Portugal.

1488: Joachim Volz 7/6/8 becomes the new syndic.

1489: The University of Frankfurt is founded. France concludes a minor war against Spain that gives them dominion over most of the Pyrenees Mountains.

1490: Frankfurt traders, nearing a century of economic dominance over European markets, began to establish monopolies.

1492: The long awaited war re-erupts between Austria and Bohemia. Bohemia catches Austria off-guard and captures Vienna initially but Austrian territory is re-captured and the war ultimately ends in a bloody draw.

The Wars of 1500 (1500-1504): At the turn of the century Europe is ablaze with war. Portugal and England war with Spain for North Africa and Spanish Galicia. France fights a tough war against Milan,the still-relevant Burgundy and her assortment of Dutch vassals, and an aggressive Venice eager to take French lands in South Italy. Austria and Bohemia-Poland predictably engage in another disastrous bloodbath against one another. None of these wars are won decisively and they set up the remainder of the century for a seemingly never-ending chain of wars over much of the territory originally sought in The Wars of 1500.

1509: Former allies, England and Portugal, go to war with each other. England had used the previous Iberian Wars to conquer territoy for herself while doing very little to restore the Portuguese lands the Spanish had taken long ago. The parasitic nature of the alliance led to inevitable war, which the English easily won.

1511: Burgundy's outward appearance of strength finally gives way to her unsolvable internal problems and the state all but dissolves.

1512: The old Teutonic Order transforms into the state of "Prussia". Eastern Europe had spent most of the past century in utter chaos but from it grew the three powerful states of Prussia, Poland, and Muscovy who had managed to conquer and consolidate sizable territories.

The English War for Austrian Italy (1512-1516): Over the decades Austria had managed to peacefully, through marriage, gain strong North Italian holdings. England, alternatively, had militarily developed a strong hold on the Italian peninsula. It didn't take very long for England's warmongering to spill over from North Africa and Iberia, and into Italy in a full-fledged war with her ally Tuscany against Austria. Although England and Tuscany captured Austria's Italian holdings, a war of opportunity had developed and suddenly England found herself once again allied with Portugal trying to hold off a strong Spain on the mainland while taking her African territories. These wars were a major investment by England and they were ultimately about to fail. France had decided it was time to intervene. England ended up losing what was left of their old French holdings, half of their Italian territory, and their vassal Tuscany. Looking to boost their much-battered prestige domestically, England formally re-branded their government as "Great Britain".

1519: France further battered down the rump-state of Burgundy through war.

1524: An ambitious Eugen Barth 3/7/9 becomes the new syndic, overthrowing the 36 year dominance of Joachim Volz. Little did he know his time in office would oversee the most important time in Frankfurt's history.

1538:

Most scholars would probably agree that Frankfurt was really founded by syndic Michael Alfter during the years of 1400-1412. He had been the guiding hand behind Frankfurt's rise to dominance in Europe's early markets and more importantly his administration became the guide for the future generations on how to best govern Frankfurt. The power of his influence can not be understated. For most of the 15th century, the governance of Frankfurt had followed on the models and principles Alfter had laid down: Internationally, Frankfurt remained the financial center of Europe and expressly stayed out of the massive wars and political turmoil that were raging inside the Holy Roman Empire. Domestically, even with the immense wealth that flooded the city, the administrative and political class of Frankfurt had managed to create a solid foundation of law and order. The prevailing of peace and tranquility in Frankfurt's political sphere can be credited to a political tradition of cooperation between the syndic's office and the city council, which created a very stable environment for it's citizens. No person more symbolized the "Alfterian" political tradition than syndic Joachim Volz. Elected in 1488, he would serve as Frankfurt's syndic until 1524. The start of the 16th century looked promising for Frankfurt's citizens. They had lived incomparably better than any other people in Europe for well over a hundred years. But cracks were beginning to emerge and little could have any citizen foreseen what historical forces were about to thrust the tiny wealthy trading city into.

Over the 15th century much of the land available in the region began to be filled with wealthy and extensive estates of the powerful merchant-princes of Frankfurt. Frankfurt as a city had long ago ran out of area to build in, and as a result a historical event began occurring. A type of contract became common in the area whereby a citizen of Frankfurt could "purchase" land from the neighboring states but still maintain citizenship and full voting right in Frankfurt. It may perhaps at first sight appear to be nonsense, to view a simple contract as a source of historical determinism, but we must look deeper to understand what it meant. The neighbors of Frankfurt had had a strange relationship with Frankfurt, for they were jealous of it's wealth and fearful of it's strength, yet felt protected and had greatly benefited from it. Many of Frankfurt's neighbors had feared what could happen if Frankfurt's economic power began translating into military power, as many people in Alfter's Frankfurt during the early 1400's had wanted. And yet the need for more land for the growing population had become critical. A triumph of peace occurred, or so it appeared. Frankfurt's neighbors were greatly concerned with selling any land away to them so contracts were designed that allowed Frankfurtian buyers to purchase land at a elevated price, but they did not actually own it because it was a lease for a hundred years, and not a real ownership. At it's time it was the perfect compromise. It almost immediately solved the land crisis Frankfurt had experienced, and Frankfurt's neighbors began seeing an unprecedented influx of income from the high taxes and highly elevated purchase costs they had set on the land, which would still belong to them after a hundred years. These "high" costs were of course easily met by Frankfurt's merchants, but what was most important was that it had averted the militarization of Frankfurt, something Frankfurt's neighbors greatly feared. The idea being that the renewing of the lease century after century depended on remaining a peaceful neighbor.

An idealistic view of the events, to be sure; but it was a typically "Alfterian" solution. It did work well for decades, but by the start of the 16th century the flaws were beginning to become more noticeable. One such example: many of the states had began making "Special Levy Acts", which meant that either the Frankfurtian owner of the land, and his many sons, would have to join the foreign army of the land he resided on, or he would have to immediately pay a sizable special war-time tax that would grant him immunity from the mobilization. Conveniently, Frankfurt's neighboring states seemed to be always declaring a war, or threaten a mobilization so as to have the money paid in advance. The peace that the "triumph of peace" had built was a parasitic one, and it was leading to a deadly clash.

Beating the long-reigning Joachim Volz was not an easy task for Eugen Barth. He had not come from a powerful trading clan, but from a military family. Frankfurt had what were probably some of the best soldiers in Europe, but many of them were foreigners. Early on in Frankfurt's history the need for soldiers was limited by the city's population. This was overcome by making a powerful recruiting program that brought over some of the best soldiers in the Holy Roman Empire with promises of luxurious estates in Frankfurt-proper and unmatchable salaries. Most of these soldiers would use this quick boost in wealth to begin entering into the new wars of finance and trade, of which Frankfurt was also unmatched. But some soldiers would remain firmly with the military, not only in their own lifetime, but by establishing a military family who's sons and grandsons would serve the future Frankfurt's needs. Eugen Barth's family had come to Frankfurt over a century ago from Brandenburg. Brandenburg had been annexed to Bohemia in a brutal war by the Bohemian Holy Roman Emperor and left people fleeing for their lives. Having heard of the drastic need for soldiers in Frankfurt, and hoping to escape desolation, swordsman Thomas Barth rode to Frankfurt and never looked back.

Eugen Barth was fundamentally not from the "Alfterian" school of thought. It was perhaps the greatest irony and paradox that trading had given Frankfurt's people extensive understanding and a deep knowledge of the intricate political order of the European states yet they were fiercely isolationist, and deeply delusional; believing they lay protected above or outside the state of affairs of all the rest of Europe. It was a world-view that Eugen Barth was never able to accept; perhaps it was the last refuge of what was left in his mind of his Brandenburg past and the horrors that befell it. Nevertheless he had to play the Frankfurtian political game to become a syndic, and he won largely on the promise that he would secure a peaceful resolution to the many problems Frankfurt's land leasers had experienced in neighboring territories. In truth his mind was held hostage to events far from Frankfurt's immediate borders. France had been slowly and steadily expanding in all directions but Barth's chief concern was the push eastward into the Holy Roman Empire. To Frankfurt's west, Bohemia and Austria had turned Central Europe into a century-long slaughtering block.

Eugen Barth's negotiations began the second he arrived into the syndic's office in 1524. He had proven a popular leader amongst every class of Frankfurt society but ten years later in 1534 he had still not managed to produce a lasting agreement that would protect Frankfurt's land interests in neighboring lands. The Alfterian restraints that had held his political mind jailed, were loosening. It had become increasingly more apparent in the negotiations that Frankfurt was ultimately being blocked from a favorable settlement, militarily. The only outcome of the negotiations would be a military one unless he surrendered to the status-quo and left Frankfurt's land leasers to the abuse of the hostile governments. Even with his military background, deciding what he needed to do was not proving easy. Frankfurt had never seen a war before. Any declaration of war against one neighbor would very likely lead to war with most of them. It was a decision that would be irreversible if he took it, he could not take it. But fate would force it.

In 1538, the hostile actions of Mainz would begin a chain of events that would change the region forever. Mainz, desperate for money from countless devastating wars, had issued a decree immediately terminating all Frankfurtian leases, unless an immediate "Loyalty Fee" was paid. Frankfurt citizens who had lived in Mainz for decades were suddenly left without their homes or wealth. It was only a matter of months before they would see the same thing occur in Wurzburg and Hessen. In Barth's head there was no more "peace". Peace meant damage to Frankfurt, peace meant fear and uncertainty. It was time for resolution and war. The city council demanded a military response, indeed many who were in the city council had lost their holdings in Mainz. For the first time, Frankfurt would assert it's power.

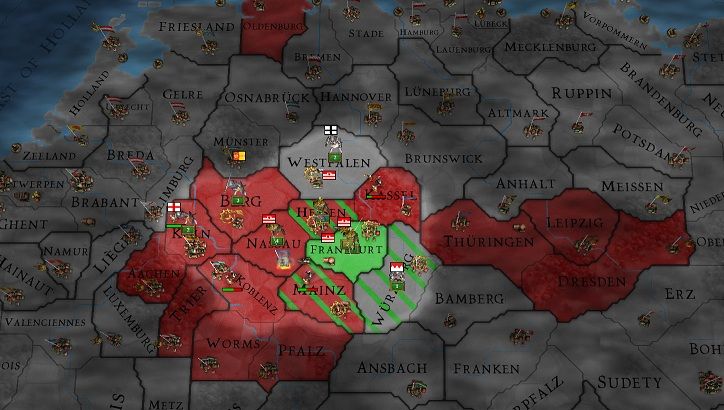

Barth harnessed the incredible wealth of Frankfurt's banks and treasury to begin amassing an army of not just citizens, but of other Germans, luring them with the same promises his ancestors had received. By 1539, he had nearly doubled the army to an incredible 21,000 soldiers. The war plan was simple. Frankfurt did not have the manpower to trade soldier for soldier with other powers and they would likely be facing every country around them. Defeating the armies first would be the priority, especially defeating them as early as possible before they could assemble into larger coalition armies.

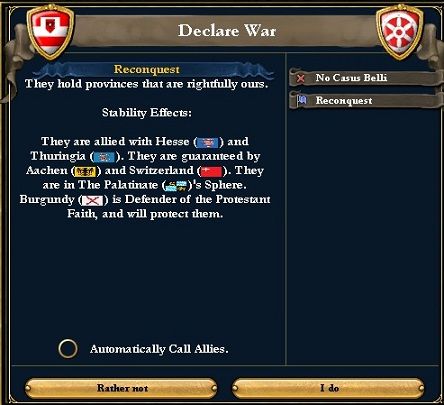

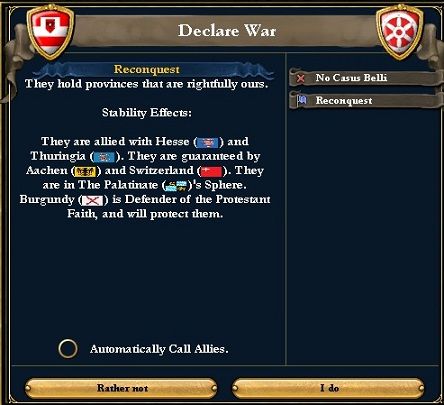

Eugen Barth would personally take a force of 3,000 infantrymen and 2,000 cavalrymen into Mainz to engage a formation of 3,000 soldiers. Meanwhile Markus Barth, Eugen Barth's uncle and the leader of Frankfurt's army, would command an army of 12,000 infantrymen and 4,000 cavalrymen and move to strike a massing of 11,000 soldiers in Hessen. After this initial stage, they would have to assess the situation and either begin besieging, or race to defeat other military formations. The plan purposely kept Frankfurt's military as close to Frankfurt as much as possible, it was certain to experience it's first ever attack and siege in this war. On January 2nd, 1540, the syndic and city council of Frankfurt, declared war on Mainz.

On January 6th both armies had arrived. Even the most patriotic and optimistic citizens in Frankfurt had no idea just how wildly successful the Frankfurtian army was about to prove.

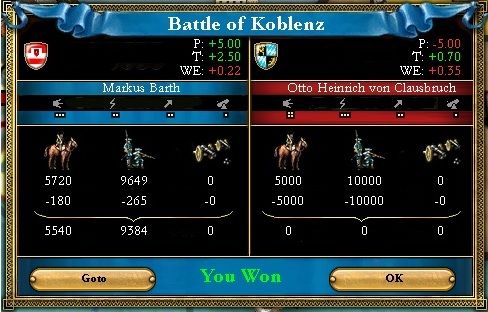

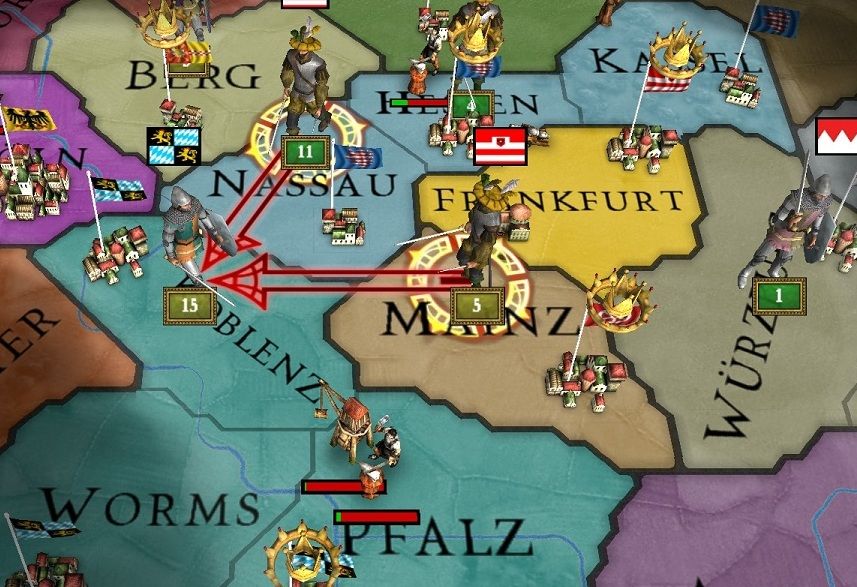

By January 9th, Markus Barth's army annihilated the forces of the Hessian king, Ludwig IV. Even Markus Barth was in shock at how easily they had just dispatched such a sizable force. He decided to leave behind 4,000 infantrymen to siege Hessen, while the rest of his army would march through Nassau and Koblenz.

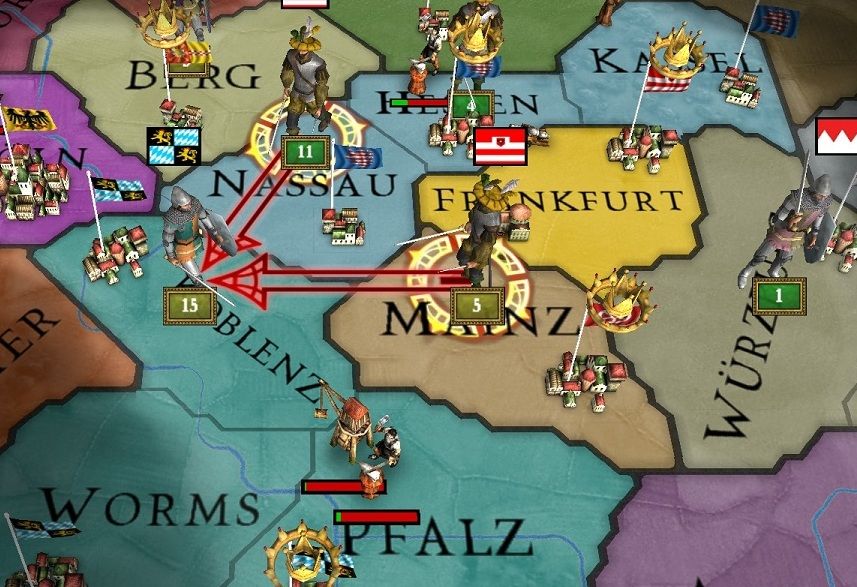

By January 10th, Eugen Barth had also experienced the great shock of success that was sparking through the Frankfurtian armies but he had no time to stay and celebrate nor to begin besieging. When his army had arrived in Mainz they had realized that a Palatinate army of 15,000 was marching from Pfalz to Koblenz. Surely the Palatinate had joined forces against Frankfurt but somehow word had not spread to them yet that they had even arrived, let alone won, in Hessen and Mainz. Eugen had narrowly avoided his own annihilation. Eugen knew this army had to be fought immediately, before it could assemble any coalition. He sent his fastest rider to find his uncle and inform him of the situation and darted at break-neck speed for Koblenz where the Palatinate host was arriving. He had to get there and engage as fast as possible before they had a chance to retreat deeper towards Pfalz, and farther away from Frankfurt.

In the early morning of January 18th, Eugen Barth arrived in Koblenz, and immediately realized that the army of 15,000 was organizing a march back to Pfalz. He wondered whether they had perhaps seen his uncle's army to the north and decided to retreat. What if they had already engaged and defeated him? He had not yet heard of Markus's stunning victory in Hessen. He would have to take a daring gamble and block their path. If the Palatinate army could not be defeated here, they would not be defeated in Pfalz. How long his 5,000 could hold was unknown but he had to hope it was long enough for Markus Barth's army to arrive.

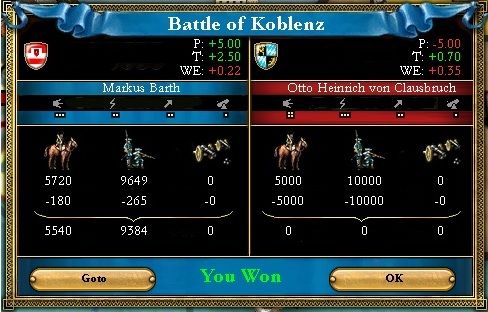

Eugen Barth's gamble would become one of the great stories of Frankfurt's military history. Eugen's army had blocked the Palatinate's path of retreat on January 18th, and had began fighting them. The Palatinate's army was desperately attempting to punch a breakthrough through Eugen's army because they had indeed been attempting to retreat from Markus Barth's incoming army. But they would never see Pfalz again. On the same day Eugen Barth had arrived to block the retreat, Markus Barth arrived to the backs of the Palatinate's 15,000 men, and had the effect of a hammer against an anvil. The likes of the butchery that occurred in Koblenz that day had not been seen in western Germany's recent history.

After 9 days of fighting, there was not a single man left alive from the host of 15,000 the Palatinate had assembled. Yet another moment that was ripe for a good Frankfurtian celebration had presented itself, but word had just arrived from the city council that a force of 6,000 men carrying the banner of the red-striped lion of Hesse was headed directly for Frankfurt. The message left Eugen wondering how his uncle had managed to miss a host of 6,000 Hessians, but the time for confronting his uncle would have to be later.

Eugen and Markus established a new plan. Markus Barth would rush back to Frankfurt to engage the Hessian sieges while Eugen would move his men to Nassau, not only to catch any forces from the west but to be able to quickly assist Markus's army should he need it in Frankfurt.

Markus Barth arrived to Frankfurt on February 10th, and quickly realized the force sieging Frankfurt was not Hessian. These were Thuringians, who had an almost identical flag.

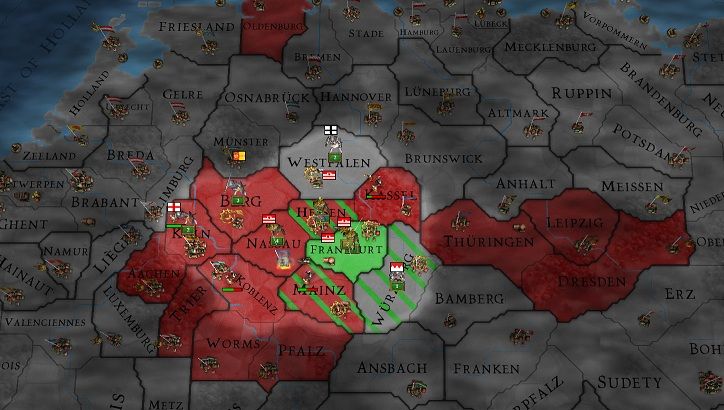

By February 16th the Thuringian army was destroyed. The Thuringians had stood no chance against Frankfurt's army. It had been succesful beyond what anyone could have expected. In barely a month and a half Frankfurt had killed and wounded 35,000 soldiers. Markus found himself concerned by the amount of different armies he had fought in such a small time span. He went to the city council and attempted to put together just how many states they were at war with.

Over the 15th century much of the land available in the region began to be filled with wealthy and extensive estates of the powerful merchant-princes of Frankfurt. Frankfurt as a city had long ago ran out of area to build in, and as a result a historical event began occurring. A type of contract became common in the area whereby a citizen of Frankfurt could "purchase" land from the neighboring states but still maintain citizenship and full voting right in Frankfurt. It may perhaps at first sight appear to be nonsense, to view a simple contract as a source of historical determinism, but we must look deeper to understand what it meant. The neighbors of Frankfurt had had a strange relationship with Frankfurt, for they were jealous of it's wealth and fearful of it's strength, yet felt protected and had greatly benefited from it. Many of Frankfurt's neighbors had feared what could happen if Frankfurt's economic power began translating into military power, as many people in Alfter's Frankfurt during the early 1400's had wanted. And yet the need for more land for the growing population had become critical. A triumph of peace occurred, or so it appeared. Frankfurt's neighbors were greatly concerned with selling any land away to them so contracts were designed that allowed Frankfurtian buyers to purchase land at a elevated price, but they did not actually own it because it was a lease for a hundred years, and not a real ownership. At it's time it was the perfect compromise. It almost immediately solved the land crisis Frankfurt had experienced, and Frankfurt's neighbors began seeing an unprecedented influx of income from the high taxes and highly elevated purchase costs they had set on the land, which would still belong to them after a hundred years. These "high" costs were of course easily met by Frankfurt's merchants, but what was most important was that it had averted the militarization of Frankfurt, something Frankfurt's neighbors greatly feared. The idea being that the renewing of the lease century after century depended on remaining a peaceful neighbor.

An idealistic view of the events, to be sure; but it was a typically "Alfterian" solution. It did work well for decades, but by the start of the 16th century the flaws were beginning to become more noticeable. One such example: many of the states had began making "Special Levy Acts", which meant that either the Frankfurtian owner of the land, and his many sons, would have to join the foreign army of the land he resided on, or he would have to immediately pay a sizable special war-time tax that would grant him immunity from the mobilization. Conveniently, Frankfurt's neighboring states seemed to be always declaring a war, or threaten a mobilization so as to have the money paid in advance. The peace that the "triumph of peace" had built was a parasitic one, and it was leading to a deadly clash.

Beating the long-reigning Joachim Volz was not an easy task for Eugen Barth. He had not come from a powerful trading clan, but from a military family. Frankfurt had what were probably some of the best soldiers in Europe, but many of them were foreigners. Early on in Frankfurt's history the need for soldiers was limited by the city's population. This was overcome by making a powerful recruiting program that brought over some of the best soldiers in the Holy Roman Empire with promises of luxurious estates in Frankfurt-proper and unmatchable salaries. Most of these soldiers would use this quick boost in wealth to begin entering into the new wars of finance and trade, of which Frankfurt was also unmatched. But some soldiers would remain firmly with the military, not only in their own lifetime, but by establishing a military family who's sons and grandsons would serve the future Frankfurt's needs. Eugen Barth's family had come to Frankfurt over a century ago from Brandenburg. Brandenburg had been annexed to Bohemia in a brutal war by the Bohemian Holy Roman Emperor and left people fleeing for their lives. Having heard of the drastic need for soldiers in Frankfurt, and hoping to escape desolation, swordsman Thomas Barth rode to Frankfurt and never looked back.

Eugen Barth was fundamentally not from the "Alfterian" school of thought. It was perhaps the greatest irony and paradox that trading had given Frankfurt's people extensive understanding and a deep knowledge of the intricate political order of the European states yet they were fiercely isolationist, and deeply delusional; believing they lay protected above or outside the state of affairs of all the rest of Europe. It was a world-view that Eugen Barth was never able to accept; perhaps it was the last refuge of what was left in his mind of his Brandenburg past and the horrors that befell it. Nevertheless he had to play the Frankfurtian political game to become a syndic, and he won largely on the promise that he would secure a peaceful resolution to the many problems Frankfurt's land leasers had experienced in neighboring territories. In truth his mind was held hostage to events far from Frankfurt's immediate borders. France had been slowly and steadily expanding in all directions but Barth's chief concern was the push eastward into the Holy Roman Empire. To Frankfurt's west, Bohemia and Austria had turned Central Europe into a century-long slaughtering block.

Eugen Barth's negotiations began the second he arrived into the syndic's office in 1524. He had proven a popular leader amongst every class of Frankfurt society but ten years later in 1534 he had still not managed to produce a lasting agreement that would protect Frankfurt's land interests in neighboring lands. The Alfterian restraints that had held his political mind jailed, were loosening. It had become increasingly more apparent in the negotiations that Frankfurt was ultimately being blocked from a favorable settlement, militarily. The only outcome of the negotiations would be a military one unless he surrendered to the status-quo and left Frankfurt's land leasers to the abuse of the hostile governments. Even with his military background, deciding what he needed to do was not proving easy. Frankfurt had never seen a war before. Any declaration of war against one neighbor would very likely lead to war with most of them. It was a decision that would be irreversible if he took it, he could not take it. But fate would force it.

In 1538, the hostile actions of Mainz would begin a chain of events that would change the region forever. Mainz, desperate for money from countless devastating wars, had issued a decree immediately terminating all Frankfurtian leases, unless an immediate "Loyalty Fee" was paid. Frankfurt citizens who had lived in Mainz for decades were suddenly left without their homes or wealth. It was only a matter of months before they would see the same thing occur in Wurzburg and Hessen. In Barth's head there was no more "peace". Peace meant damage to Frankfurt, peace meant fear and uncertainty. It was time for resolution and war. The city council demanded a military response, indeed many who were in the city council had lost their holdings in Mainz. For the first time, Frankfurt would assert it's power.

Barth harnessed the incredible wealth of Frankfurt's banks and treasury to begin amassing an army of not just citizens, but of other Germans, luring them with the same promises his ancestors had received. By 1539, he had nearly doubled the army to an incredible 21,000 soldiers. The war plan was simple. Frankfurt did not have the manpower to trade soldier for soldier with other powers and they would likely be facing every country around them. Defeating the armies first would be the priority, especially defeating them as early as possible before they could assemble into larger coalition armies.

Eugen Barth would personally take a force of 3,000 infantrymen and 2,000 cavalrymen into Mainz to engage a formation of 3,000 soldiers. Meanwhile Markus Barth, Eugen Barth's uncle and the leader of Frankfurt's army, would command an army of 12,000 infantrymen and 4,000 cavalrymen and move to strike a massing of 11,000 soldiers in Hessen. After this initial stage, they would have to assess the situation and either begin besieging, or race to defeat other military formations. The plan purposely kept Frankfurt's military as close to Frankfurt as much as possible, it was certain to experience it's first ever attack and siege in this war. On January 2nd, 1540, the syndic and city council of Frankfurt, declared war on Mainz.

On January 6th both armies had arrived. Even the most patriotic and optimistic citizens in Frankfurt had no idea just how wildly successful the Frankfurtian army was about to prove.

By January 9th, Markus Barth's army annihilated the forces of the Hessian king, Ludwig IV. Even Markus Barth was in shock at how easily they had just dispatched such a sizable force. He decided to leave behind 4,000 infantrymen to siege Hessen, while the rest of his army would march through Nassau and Koblenz.

By January 10th, Eugen Barth had also experienced the great shock of success that was sparking through the Frankfurtian armies but he had no time to stay and celebrate nor to begin besieging. When his army had arrived in Mainz they had realized that a Palatinate army of 15,000 was marching from Pfalz to Koblenz. Surely the Palatinate had joined forces against Frankfurt but somehow word had not spread to them yet that they had even arrived, let alone won, in Hessen and Mainz. Eugen had narrowly avoided his own annihilation. Eugen knew this army had to be fought immediately, before it could assemble any coalition. He sent his fastest rider to find his uncle and inform him of the situation and darted at break-neck speed for Koblenz where the Palatinate host was arriving. He had to get there and engage as fast as possible before they had a chance to retreat deeper towards Pfalz, and farther away from Frankfurt.

In the early morning of January 18th, Eugen Barth arrived in Koblenz, and immediately realized that the army of 15,000 was organizing a march back to Pfalz. He wondered whether they had perhaps seen his uncle's army to the north and decided to retreat. What if they had already engaged and defeated him? He had not yet heard of Markus's stunning victory in Hessen. He would have to take a daring gamble and block their path. If the Palatinate army could not be defeated here, they would not be defeated in Pfalz. How long his 5,000 could hold was unknown but he had to hope it was long enough for Markus Barth's army to arrive.

Eugen Barth's gamble would become one of the great stories of Frankfurt's military history. Eugen's army had blocked the Palatinate's path of retreat on January 18th, and had began fighting them. The Palatinate's army was desperately attempting to punch a breakthrough through Eugen's army because they had indeed been attempting to retreat from Markus Barth's incoming army. But they would never see Pfalz again. On the same day Eugen Barth had arrived to block the retreat, Markus Barth arrived to the backs of the Palatinate's 15,000 men, and had the effect of a hammer against an anvil. The likes of the butchery that occurred in Koblenz that day had not been seen in western Germany's recent history.

After 9 days of fighting, there was not a single man left alive from the host of 15,000 the Palatinate had assembled. Yet another moment that was ripe for a good Frankfurtian celebration had presented itself, but word had just arrived from the city council that a force of 6,000 men carrying the banner of the red-striped lion of Hesse was headed directly for Frankfurt. The message left Eugen wondering how his uncle had managed to miss a host of 6,000 Hessians, but the time for confronting his uncle would have to be later.

Eugen and Markus established a new plan. Markus Barth would rush back to Frankfurt to engage the Hessian sieges while Eugen would move his men to Nassau, not only to catch any forces from the west but to be able to quickly assist Markus's army should he need it in Frankfurt.

Markus Barth arrived to Frankfurt on February 10th, and quickly realized the force sieging Frankfurt was not Hessian. These were Thuringians, who had an almost identical flag.

By February 16th the Thuringian army was destroyed. The Thuringians had stood no chance against Frankfurt's army. It had been succesful beyond what anyone could have expected. In barely a month and a half Frankfurt had killed and wounded 35,000 soldiers. Markus found himself concerned by the amount of different armies he had fought in such a small time span. He went to the city council and attempted to put together just how many states they were at war with.

Well, you can triple Frankfurt's size in this war at least. You should be able to the coast the war from here on out.