Nice. I saw that picture and thought 'my God, is that Mark Twain!' Is this an indication of things to come?

A Special Providence

- Thread starter Director

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

I can't help but wonder at the book he will write if he ever discovers the true nature of his boss...

Fulcrumvale said:I can't help but wonder at the book he will write if he ever discovers the true nature of his boss...

Has anyone else read any of the renditions of The Mysterious Stranger? He had a few versions which he never really got around to completing, but they're interesting. They're all about predestination, basically. It is also apparant they were written during his bitter end time.

coz1 - what Missouri exported to Kansas in the late 1850's it kept at home during the Civil War. That's part of what made Missouri such a bushwhacking hell during the war and bred all those outlaws afterwards... the James gang, the Youngers, others.

You certainly know something about that. Everyone else should go read coz1's 'Into the West' located on this very same Victoria forum. Go now, you'll thank me later.

Everyone else should go read coz1's 'Into the West' located on this very same Victoria forum. Go now, you'll thank me later.

The 'villain' who took a sword to those farmers in the middle of the night was none other than John Brown.

Vann the Red - It is certainly true that sectional disagreement is curdling into hatred. As for the rest... continued next time. We have a lot more heat to apply to this kettle.

We have a lot more heat to apply to this kettle.

TheExecuter - Charles Sumner did give a speech, though the date is different from this timeline. It was possibly the most insulting, incendiary and vicious speech ever delivered in the US Senate, and much of its sting came from the parts that were the most truthful. Brooks did whip Sumner with a cane, and Southerners sent Brooks new canes and begged for pieces of the broken one 'as holy relics'. The ensuing outrage in newspapers of both sides was beyond even the partisan warfare we see today.

kbromer - glad to oblige and I am honored to be your choice. I'm finding these 'history book' sections relatively easy to write, so you'll see another update soon.

J. Passepartout - part of the line I'm walking is to reference historical people while having them slightly different from the way we know of them. Hence earlier on I referenced several operas by EA Poe.

I needed someone who would be a recognizable name yet born around the right time. My other choice would have been Dostoyevski. Imagine my surprise when I found out that Clemens spent some time (around age 18) working for newspapers in New York and other cities.

Imagine my surprise when I found out that Clemens spent some time (around age 18) working for newspapers in New York and other cities.

You will see a fair number of 'historical' people in this AAR - how could I resist? - but they will be changed by events and circumstances.

I've never read any of that particular work but I will confess that bitter Twain is still a cut above almost anyone else. That man knew how to tell a story.

Fulcrumvale - Read some of 'The Gilded Age', if you haven't already. It has a lot to say about robber-baron capitalism. And 'A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court' deals with time travel... and knights, but not time-traveling knights... Hmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmm.

You certainly know something about that.

The 'villain' who took a sword to those farmers in the middle of the night was none other than John Brown.

Vann the Red - It is certainly true that sectional disagreement is curdling into hatred. As for the rest... continued next time.

TheExecuter - Charles Sumner did give a speech, though the date is different from this timeline. It was possibly the most insulting, incendiary and vicious speech ever delivered in the US Senate, and much of its sting came from the parts that were the most truthful. Brooks did whip Sumner with a cane, and Southerners sent Brooks new canes and begged for pieces of the broken one 'as holy relics'. The ensuing outrage in newspapers of both sides was beyond even the partisan warfare we see today.

kbromer - glad to oblige and I am honored to be your choice. I'm finding these 'history book' sections relatively easy to write, so you'll see another update soon.

J. Passepartout - part of the line I'm walking is to reference historical people while having them slightly different from the way we know of them. Hence earlier on I referenced several operas by EA Poe.

I needed someone who would be a recognizable name yet born around the right time. My other choice would have been Dostoyevski.

You will see a fair number of 'historical' people in this AAR - how could I resist? - but they will be changed by events and circumstances.

I've never read any of that particular work but I will confess that bitter Twain is still a cut above almost anyone else. That man knew how to tell a story.

Fulcrumvale - Read some of 'The Gilded Age', if you haven't already. It has a lot to say about robber-baron capitalism. And 'A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court' deals with time travel... and knights, but not time-traveling knights... Hmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmm.

Ugh. I had heard of Bleeding Kansas, but I had never realized just how ugly it really was. If only half of the incidents you describe were historical, it must have been akin to a civil war. Not the Civil War (in caps), where Grant met Lee and Sherman burned Atlanta, but nasty bloodletting where the victims are almost exclusively civilian.

If your writings are grounded in reality, then you have shown me a facet of American history I knew next to nothing about. For that, I thank you.

If your writings are grounded in reality, then you have shown me a facet of American history I knew next to nothing about. For that, I thank you.

Kansas turned into a medium-level guerilla war. Once the Civil War broke out, the people who had been terrorizing Kansas began terrorizing Union sympathizers in Missouri. Quantrill and the other bushwhackers also spawned most of the bank robbers and gangs of the post-war period. Most of what I described was historical, but instead of my Battle of Lawrence there was a Sack of Lawrence. Less bloodshed, more damage.

Yes, it was bad. How bad? Kansas reliably turned in the highest Republican percentage of voters for almost a century after the war. Bad enough that three or four territorial governors quit or were driven out, including some who came in staunch pro-slavery men and went out convinced the North was the injured party. That bad.

Yes, it was bad. How bad? Kansas reliably turned in the highest Republican percentage of voters for almost a century after the war. Bad enough that three or four territorial governors quit or were driven out, including some who came in staunch pro-slavery men and went out convinced the North was the injured party. That bad.

Of all the peoples of the Earth none were more enraptured by the railroad than the Britons and the Yankees, an unsurprising assertion perhaps in view of their common ancestry. But what was for Britain a path to wealth and industrial power was for the United States no less than a necessity for survival. No country, be it a democratic republic or despotic tyranny, no country can long remain intact when it cannot communicate with its extremities. The parallels with the American Revolution (and to other rebellions successful or otherwise) are numerous and have been expounded at greater length and depth than will be attempted here. Simply let us say that settlement beyond the barrier of the Appalachians would be slow and dangerous, and their markets dangerously separate from the Atlantic Coast, until the United States could develop rapid and reliable transportation to the interior.

The Erie Canal was a major step toward this goal and other canal projects flourished as investors lined up to lend their money to the cause. The interior of America was so vast and so rich that opening it to trade could be fabulously profitable… and, as investors learned to their sorrow, sometimes risky and expensive. Besides the vagaries of chance there was the looming mass of the Appalachian Mountains, which blocked the flat course desirable for the cheap and easy construction of canals. The development of railroads, and the use of steam-powered locomotives, was the answer to many a prayer.

Railroading in Britain was a scientific enterprise. Right-of-ways were fenced and guarded, grades were gentle, curves almost non-existent. Master engineers created state-of-the-art tunnels and bridges so that the rails could run unswerving as an arrow from city to city, and British railroads were justly famous world-wide for their speed, safety and efficient schedules.

Building a railroad in America was an adventure, in the sense that it was dangerous and dirty and peopled by desperate men. Much of the land had not been surveyed, even in the original Atlantic states, and there was no means to acquire the land needed for a right-of-way except to dicker with each individual land-owner along the route. America did not have the British advantage of hundreds of years of civilization to smooth the land, so railroad beds were forced to bridge countless streams, hack through forests and climb mountains. Too, American railroads suffered from scale: the mileage of track needed to connect the several states was many times more than that required to link every village and hamlet in Britain. America was also thinly populated compared to Britain, so the money-making connections were much greater distances apart with little in between of immediate economic value.

All this meant that a uniquely American approach to building railroads was needed. ‘Lay it down, hammer it up, get it running’ was the cry, and so they did. Rare were stone bridges and extensive tunnels, or even smooth, flat miles of track. Common instead were tight curves and steep grades, with rails hurtling into space over wooden bridges made of stringers and promises. Building cheaply meant a longer line could be rapidly opened and its profits used to maintain and improve the bed, which meant the road might last long enough to make repayment on the investment. But sharp curves and slipshod construction imposed a serious constraint on the type and size of locomotives that could be used. Bigger engines were usually longer and thus had to have shallow, gradual curves lest they derail, and small engines were usually slow, pulled less weight of cargo and thus were unprofitable.

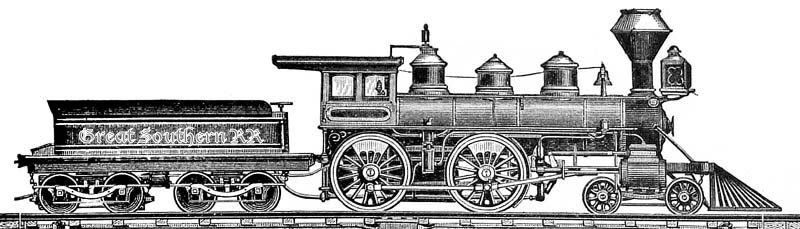

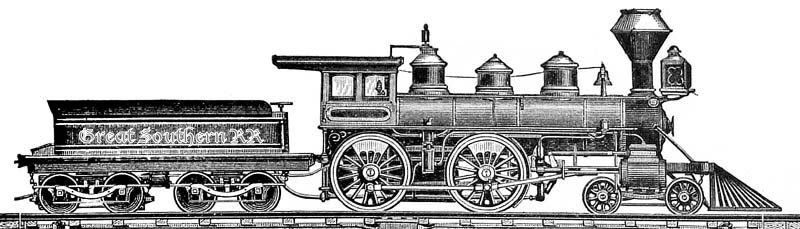

In the late 1840’s an American railroad man solved the problem with an invention so profound and perfect it is still in use today on locomotives around the world. Ahead of the driver wheels – the ones connected to the steam pistons – he put four small wheels on a square platform and mounted it on a pivot underneath the nose of the engine. As the track curved the engine would be led ‘by the nose’ around the bend, and the use of four wheels on the ‘truck’ gave it stability even at high speeds. Almost overnight this system spread to almost every locomotive, allowing large engines to run at high speed over curvy, uneven track. Almost overnight, the American method of railroad construction was shown to be financially viable, and the mileage of track doubled – redoubled – until the United States had more miles of track than any other nation and bid fair to have more railroad miles than every other nation, combined.

4-4-0 ‘American’ style locomotive of the Great Southern RR, showing its four-wheeled pivoting truck under the front of the engine.

For the saga of the Great Southern see the link in my sig.

Of course, such massive investment was beyond the means of American capital. But everyone could see the vast profits in cattle, grain and timber – to mention but three – to be reaped from the American heartland. So financiers in Britain, France and elsewhere joined Americans in purchasing railroad stocks and bonds. The onset of the Crimean War made purchases of Russian grain impossible, but American wheat and corn could be quickly and cheaply railroaded from Iowa, Illinois, Indiana and Ohio to the Atlantic ports. Under this stimulus, railroad construction exploded. Unable to supply the iron and tools from domestic sources, capital flowed to Europe and Britain, feeding the expansion of iron and goods production there and underpinning a long, sustained economic boom.

With the end of the Crimean War and a return to previous patterns of commerce, the United States found itself over-built on rail capacity. The length and power of the economic boom had led many industries to over-invest in capacity, hence most commodities were over-supplied. Attempts to gain market share by cutting prices rebounded as credit contracted. Freely available only a short while before, the expense of the Crimean War absorbed much of the available credit in Europe. American banks were awash in stocks and bonds (chiefly railroad securities) with little cash reserve on hand. For most of 1857 the financial markets had been nervous and uncertain, a function of the over-supply of commodities, tightening credit and renewed competition from Russian agricultural products.

On Monday, August 24th of 1857, a small bank in Baltimore found itself the scene of a criminal investigation when it was discovered that a trusted employee had absconded with a substantial portion of the cash reserves. The news, spread by telegraph and newspaper, caused a small run on deposits in banks across the country as some nervous customers decided to repossess their money. On Wednesday, just as the scare was dying down, the New England Rope and Cordage Company of Andover, Massachusetts announced it was unable to continue in operation. NE Rope had long been a favorite investment of blue-blooded New Englanders; it was a fusty, conservative company with gilt-edged stock certificates that paid high dividends, but it had been unwilling to modernize and its lack of competitiveness was directly related to its collapsing bottom line. Anyone who had studied the company would have known it was losing money, but its reputation was so solid that its insolvency came as a severe shock. As the ripples spread outward, and as banks closed for lack of funds and credit evaporated, demand for goods and commodities temporarily collapsed. Shops and businesses began shutting their doors by the hundreds and financial men braced themselves for the pain of the contraction.

British banks had been removing funds deposited in American banks since the Crimean War, but the recent poor financial news had increased this from a trickle to a stream. The evidence of British lack of faith in the American market prompted mad scenes as depositors struggled to get their funds out of banks and investment houses, prompting even sound institutions to temporarily cease operations in hopes that cooler heads would prevail and the panic subside. Following suit the various exchanges of Wall Street also voluntarily shut down.

With so many hundreds of small, short-line railroads built in the previous decade on cheap European credit and dependent on good prices for freight for their operating capital it should come as no surprise that, as the dominos began to fall, railroads too began to topple. What once had been secure and profitable investments were turned overnight into piles of almost worthless paper, prompting investors to dump all of their American holdings whether sound or not. The imperturbable Pennsylvania Railroad announced it would miss a dividend for the first time in its history, and only the personal character and cash reserves of titans like Vanderbilt and Morrison allowed the New York Central to be saved from bankruptcy.

The sum of all this bad news was the worst depression of the American economy since the catastrophies of the last Jackson administration. Nor were the effects limited to the United States. British and European money had underwritten the vast expansion in American manufacturing and transportation infrastructure and helped the United States become a formidable economic power. The collapse of those investments and the concomitant economic damage in Britain and Europe brought home the lesson that the United States had become an important part of a global financial system. While Britain, France and to a lesser degree Prussia and the Netherlands might be the most important economies in Europe, in the future none would be able to ignore the effects of the American market.

Most investors expected the setbacks to be severe but short-lived; once the panic had subsided and business resumed, they reasoned, a prudent man would be able to pick up enormous quantities of securities and sound – if overextended – businesses at fire-sale prices. This analysis would undoubtedly have proven correct had other factors not come into play, namely the monetary supply and the loss of the steamship ‘Ohio’. Many banks and businesses had been holding on by their fingernails while awaiting the quarterly shipment of gold from California and Idaho. This specie would calm fears and allow banks to make payments to those depositors who were still nervous. Cruelly, the ‘Ohio’ was rammed by the steamship ‘Globe’ and sank just off the Perth Amboy light with more than $12 million in federal and private specie in her holds. Although much of the precious metal was later salvaged, the loss set off another round of bank and business closings and persuaded the Wall Street markets to again close for a week to recover their balance.

As noted, the wide-spread effects of the financial panic took most contemporary investors by surprise. A collapse of over-valued American railway securities was not expected to cause mills in Europe to close and, by that, drop the value of bales of cotton to almost nothing, but as noted above the American economy and financial markets were now large enough to exert considerable pressure on European markets. One innovative solution, rapidly copied in other commodities, was the creation of cotton ‘sinking fund’. First championed by the New York ‘Telegraph’ and initially paid for by Morrison, the syndicate bought up cotton when it was cheap, thus raising the price, preserved it in concrete warehouses and released it for higher prices when the market recovered. The financial gains were small but real, and the overall effect was to stabilize cotton prices in good times and bad.

The newly-elected administration of President Jesse Bright received a sizable amount of the blame for the depression, in particular from the Northern Democrats whose votes had provided the margin of victory in the last election. In the spring session of Congress the Democrats had used their waning strength in Congress to push through a reduction in the Protective Tariff. This was popular in the solidly Democratic South, which wanted to be able to purchase goods cheaply from abroad. It was deeply unpopular in the Northern Democratic strongholds of Maryland, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and New York as these states had become manufacturing centers. British goods were still cheaper and perceived to be of better quality than American wares, though the gaps were narrowing, and the Protective Tariff was seen as essential to the economic health of this Lower North region. Many newspaper editors there opined that the blame for the Panic of 1857 could be placed squarely on the reduction of the Protective Tariff.

Along with the reduction of the Protective Tariff, the first session of Congress debated and passed a series of measures that would have gladdened the heart of a Whig of times gone by. Proceeds from Federal lands were to be made available for the founding of state universities, and for the construction of the Pacific Railroad. The cost of purchasing land would be reduced for any family that wished to emigrate to the western territories, a measure that was designed to flood the vacant lands of the interior with settlers. The margin of victory was small for each, and the slave states voted almost in a bloc in opposition, but deals were made and each was shepherded to an affirmative vote. Delegations of Southern Congressmen then descended upon the White House threatening disunion, and President Bright dutifully vetoed each measure. Howls of ‘outrage’ and ‘betrayal’ ensued, and popular discontent was fueled white-hot by Theodore Judah’s pointed newspaper columns, in which he wrote that a Pacific railroad could have carried the ‘Ohio’ gold in one-tenth the time, at one-twentieth the cost, and remarked in a widely quoted quip that, ‘railroads do not sink’.

At the urging of the Secretaries of War and State a trade delegation was dispatched to Mexico. Experts in chemical production, mining and railroading were employed by American companies to exploit Mexican resources, for which those companies were well compensated. As President Bright was known to favor strong, peaceful ties with Mexico, and as a stronger Mexico was thought less likely to be a target for European expansion, American technical and financial assistance was liberally applied. In return the United States received hundreds of Prussian breech-loading needle guns, which were supposed to be a state secret but which had been supplied to a monarchist party. Needless to say these received the most meticulous scrutiny from Army officers and American gun manufacturers alike.

The Army was increased by the addition of two divisions of troops recruited from the tribes of Madagascar. Strengthened by a brigade of elite troops, these units were intended to be used for maintaining the peace and securing the seacoast of the giant island from the pirates of Zanzibar and Oman. But the unexpected mutiny of previously loyal Indian troops against British rule caused the new African units to be intermixed with infantry divisions recruited from the Creoles of Hispaniola as insurance against an uprising.

In New York the eccentric genius John Ericsson had accepted a contract from the Tsar of Russia for a new type of coast-defense ship. Intended to counter the sort of iron-plated floating battery the Royal Navy had employed against fortifications in the Crimea and in the Baltic, Ericsson’s design resembled nothing so much as an armor-plated raft topped by a rotating cylinder, from which emerged the muzzles of two large guns. It was fast, nimble and hard to hit, but the extremely low freeboard meant that waves would wash over it in anything but a very calm sea. Two ships were laid down to this radical design, but public feeling still ran high against Russia and it was decided not to allow the armored ships to be delivered to their navy. In its last act of the spring session Congress appropriated funds and the cash-strapped Russians agreed to sell. Named ‘Monitor’ and ‘Union’ these two prototypes were taken into the US Navy, and the ranks of the officer corps were soon split into pro- and anti-ironclad factions. When the economy descended into the Panic of 1857 in September the appropriated funds were not disbursed, leading Ericsson to sue for payment. The case would wend its way through the courts for years, embittering Ericsson against the Congress and, unfairly, against the Navy.

But it was to the Supreme Court that all eyes would soon turn. Against the backdrop of Bloody Kansas and a financial collapse, the President and other prominent men urged the justices to settle by decision what the Congress could not legislate. Taking up his pen, Chief Justice Roger Taney intended to use two cases before the Court to ‘annihilate, for all time,’ the legal arguments against the extension of slavery. As with so many other men, he had completely mistaken the temper of the times.

The Erie Canal was a major step toward this goal and other canal projects flourished as investors lined up to lend their money to the cause. The interior of America was so vast and so rich that opening it to trade could be fabulously profitable… and, as investors learned to their sorrow, sometimes risky and expensive. Besides the vagaries of chance there was the looming mass of the Appalachian Mountains, which blocked the flat course desirable for the cheap and easy construction of canals. The development of railroads, and the use of steam-powered locomotives, was the answer to many a prayer.

Railroading in Britain was a scientific enterprise. Right-of-ways were fenced and guarded, grades were gentle, curves almost non-existent. Master engineers created state-of-the-art tunnels and bridges so that the rails could run unswerving as an arrow from city to city, and British railroads were justly famous world-wide for their speed, safety and efficient schedules.

Building a railroad in America was an adventure, in the sense that it was dangerous and dirty and peopled by desperate men. Much of the land had not been surveyed, even in the original Atlantic states, and there was no means to acquire the land needed for a right-of-way except to dicker with each individual land-owner along the route. America did not have the British advantage of hundreds of years of civilization to smooth the land, so railroad beds were forced to bridge countless streams, hack through forests and climb mountains. Too, American railroads suffered from scale: the mileage of track needed to connect the several states was many times more than that required to link every village and hamlet in Britain. America was also thinly populated compared to Britain, so the money-making connections were much greater distances apart with little in between of immediate economic value.

All this meant that a uniquely American approach to building railroads was needed. ‘Lay it down, hammer it up, get it running’ was the cry, and so they did. Rare were stone bridges and extensive tunnels, or even smooth, flat miles of track. Common instead were tight curves and steep grades, with rails hurtling into space over wooden bridges made of stringers and promises. Building cheaply meant a longer line could be rapidly opened and its profits used to maintain and improve the bed, which meant the road might last long enough to make repayment on the investment. But sharp curves and slipshod construction imposed a serious constraint on the type and size of locomotives that could be used. Bigger engines were usually longer and thus had to have shallow, gradual curves lest they derail, and small engines were usually slow, pulled less weight of cargo and thus were unprofitable.

In the late 1840’s an American railroad man solved the problem with an invention so profound and perfect it is still in use today on locomotives around the world. Ahead of the driver wheels – the ones connected to the steam pistons – he put four small wheels on a square platform and mounted it on a pivot underneath the nose of the engine. As the track curved the engine would be led ‘by the nose’ around the bend, and the use of four wheels on the ‘truck’ gave it stability even at high speeds. Almost overnight this system spread to almost every locomotive, allowing large engines to run at high speed over curvy, uneven track. Almost overnight, the American method of railroad construction was shown to be financially viable, and the mileage of track doubled – redoubled – until the United States had more miles of track than any other nation and bid fair to have more railroad miles than every other nation, combined.

4-4-0 ‘American’ style locomotive of the Great Southern RR, showing its four-wheeled pivoting truck under the front of the engine.

For the saga of the Great Southern see the link in my sig.

Of course, such massive investment was beyond the means of American capital. But everyone could see the vast profits in cattle, grain and timber – to mention but three – to be reaped from the American heartland. So financiers in Britain, France and elsewhere joined Americans in purchasing railroad stocks and bonds. The onset of the Crimean War made purchases of Russian grain impossible, but American wheat and corn could be quickly and cheaply railroaded from Iowa, Illinois, Indiana and Ohio to the Atlantic ports. Under this stimulus, railroad construction exploded. Unable to supply the iron and tools from domestic sources, capital flowed to Europe and Britain, feeding the expansion of iron and goods production there and underpinning a long, sustained economic boom.

With the end of the Crimean War and a return to previous patterns of commerce, the United States found itself over-built on rail capacity. The length and power of the economic boom had led many industries to over-invest in capacity, hence most commodities were over-supplied. Attempts to gain market share by cutting prices rebounded as credit contracted. Freely available only a short while before, the expense of the Crimean War absorbed much of the available credit in Europe. American banks were awash in stocks and bonds (chiefly railroad securities) with little cash reserve on hand. For most of 1857 the financial markets had been nervous and uncertain, a function of the over-supply of commodities, tightening credit and renewed competition from Russian agricultural products.

On Monday, August 24th of 1857, a small bank in Baltimore found itself the scene of a criminal investigation when it was discovered that a trusted employee had absconded with a substantial portion of the cash reserves. The news, spread by telegraph and newspaper, caused a small run on deposits in banks across the country as some nervous customers decided to repossess their money. On Wednesday, just as the scare was dying down, the New England Rope and Cordage Company of Andover, Massachusetts announced it was unable to continue in operation. NE Rope had long been a favorite investment of blue-blooded New Englanders; it was a fusty, conservative company with gilt-edged stock certificates that paid high dividends, but it had been unwilling to modernize and its lack of competitiveness was directly related to its collapsing bottom line. Anyone who had studied the company would have known it was losing money, but its reputation was so solid that its insolvency came as a severe shock. As the ripples spread outward, and as banks closed for lack of funds and credit evaporated, demand for goods and commodities temporarily collapsed. Shops and businesses began shutting their doors by the hundreds and financial men braced themselves for the pain of the contraction.

British banks had been removing funds deposited in American banks since the Crimean War, but the recent poor financial news had increased this from a trickle to a stream. The evidence of British lack of faith in the American market prompted mad scenes as depositors struggled to get their funds out of banks and investment houses, prompting even sound institutions to temporarily cease operations in hopes that cooler heads would prevail and the panic subside. Following suit the various exchanges of Wall Street also voluntarily shut down.

With so many hundreds of small, short-line railroads built in the previous decade on cheap European credit and dependent on good prices for freight for their operating capital it should come as no surprise that, as the dominos began to fall, railroads too began to topple. What once had been secure and profitable investments were turned overnight into piles of almost worthless paper, prompting investors to dump all of their American holdings whether sound or not. The imperturbable Pennsylvania Railroad announced it would miss a dividend for the first time in its history, and only the personal character and cash reserves of titans like Vanderbilt and Morrison allowed the New York Central to be saved from bankruptcy.

The sum of all this bad news was the worst depression of the American economy since the catastrophies of the last Jackson administration. Nor were the effects limited to the United States. British and European money had underwritten the vast expansion in American manufacturing and transportation infrastructure and helped the United States become a formidable economic power. The collapse of those investments and the concomitant economic damage in Britain and Europe brought home the lesson that the United States had become an important part of a global financial system. While Britain, France and to a lesser degree Prussia and the Netherlands might be the most important economies in Europe, in the future none would be able to ignore the effects of the American market.

Most investors expected the setbacks to be severe but short-lived; once the panic had subsided and business resumed, they reasoned, a prudent man would be able to pick up enormous quantities of securities and sound – if overextended – businesses at fire-sale prices. This analysis would undoubtedly have proven correct had other factors not come into play, namely the monetary supply and the loss of the steamship ‘Ohio’. Many banks and businesses had been holding on by their fingernails while awaiting the quarterly shipment of gold from California and Idaho. This specie would calm fears and allow banks to make payments to those depositors who were still nervous. Cruelly, the ‘Ohio’ was rammed by the steamship ‘Globe’ and sank just off the Perth Amboy light with more than $12 million in federal and private specie in her holds. Although much of the precious metal was later salvaged, the loss set off another round of bank and business closings and persuaded the Wall Street markets to again close for a week to recover their balance.

As noted, the wide-spread effects of the financial panic took most contemporary investors by surprise. A collapse of over-valued American railway securities was not expected to cause mills in Europe to close and, by that, drop the value of bales of cotton to almost nothing, but as noted above the American economy and financial markets were now large enough to exert considerable pressure on European markets. One innovative solution, rapidly copied in other commodities, was the creation of cotton ‘sinking fund’. First championed by the New York ‘Telegraph’ and initially paid for by Morrison, the syndicate bought up cotton when it was cheap, thus raising the price, preserved it in concrete warehouses and released it for higher prices when the market recovered. The financial gains were small but real, and the overall effect was to stabilize cotton prices in good times and bad.

The newly-elected administration of President Jesse Bright received a sizable amount of the blame for the depression, in particular from the Northern Democrats whose votes had provided the margin of victory in the last election. In the spring session of Congress the Democrats had used their waning strength in Congress to push through a reduction in the Protective Tariff. This was popular in the solidly Democratic South, which wanted to be able to purchase goods cheaply from abroad. It was deeply unpopular in the Northern Democratic strongholds of Maryland, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and New York as these states had become manufacturing centers. British goods were still cheaper and perceived to be of better quality than American wares, though the gaps were narrowing, and the Protective Tariff was seen as essential to the economic health of this Lower North region. Many newspaper editors there opined that the blame for the Panic of 1857 could be placed squarely on the reduction of the Protective Tariff.

Along with the reduction of the Protective Tariff, the first session of Congress debated and passed a series of measures that would have gladdened the heart of a Whig of times gone by. Proceeds from Federal lands were to be made available for the founding of state universities, and for the construction of the Pacific Railroad. The cost of purchasing land would be reduced for any family that wished to emigrate to the western territories, a measure that was designed to flood the vacant lands of the interior with settlers. The margin of victory was small for each, and the slave states voted almost in a bloc in opposition, but deals were made and each was shepherded to an affirmative vote. Delegations of Southern Congressmen then descended upon the White House threatening disunion, and President Bright dutifully vetoed each measure. Howls of ‘outrage’ and ‘betrayal’ ensued, and popular discontent was fueled white-hot by Theodore Judah’s pointed newspaper columns, in which he wrote that a Pacific railroad could have carried the ‘Ohio’ gold in one-tenth the time, at one-twentieth the cost, and remarked in a widely quoted quip that, ‘railroads do not sink’.

At the urging of the Secretaries of War and State a trade delegation was dispatched to Mexico. Experts in chemical production, mining and railroading were employed by American companies to exploit Mexican resources, for which those companies were well compensated. As President Bright was known to favor strong, peaceful ties with Mexico, and as a stronger Mexico was thought less likely to be a target for European expansion, American technical and financial assistance was liberally applied. In return the United States received hundreds of Prussian breech-loading needle guns, which were supposed to be a state secret but which had been supplied to a monarchist party. Needless to say these received the most meticulous scrutiny from Army officers and American gun manufacturers alike.

The Army was increased by the addition of two divisions of troops recruited from the tribes of Madagascar. Strengthened by a brigade of elite troops, these units were intended to be used for maintaining the peace and securing the seacoast of the giant island from the pirates of Zanzibar and Oman. But the unexpected mutiny of previously loyal Indian troops against British rule caused the new African units to be intermixed with infantry divisions recruited from the Creoles of Hispaniola as insurance against an uprising.

In New York the eccentric genius John Ericsson had accepted a contract from the Tsar of Russia for a new type of coast-defense ship. Intended to counter the sort of iron-plated floating battery the Royal Navy had employed against fortifications in the Crimea and in the Baltic, Ericsson’s design resembled nothing so much as an armor-plated raft topped by a rotating cylinder, from which emerged the muzzles of two large guns. It was fast, nimble and hard to hit, but the extremely low freeboard meant that waves would wash over it in anything but a very calm sea. Two ships were laid down to this radical design, but public feeling still ran high against Russia and it was decided not to allow the armored ships to be delivered to their navy. In its last act of the spring session Congress appropriated funds and the cash-strapped Russians agreed to sell. Named ‘Monitor’ and ‘Union’ these two prototypes were taken into the US Navy, and the ranks of the officer corps were soon split into pro- and anti-ironclad factions. When the economy descended into the Panic of 1857 in September the appropriated funds were not disbursed, leading Ericsson to sue for payment. The case would wend its way through the courts for years, embittering Ericsson against the Congress and, unfairly, against the Navy.

But it was to the Supreme Court that all eyes would soon turn. Against the backdrop of Bloody Kansas and a financial collapse, the President and other prominent men urged the justices to settle by decision what the Congress could not legislate. Taking up his pen, Chief Justice Roger Taney intended to use two cases before the Court to ‘annihilate, for all time,’ the legal arguments against the extension of slavery. As with so many other men, he had completely mistaken the temper of the times.

Last edited:

Fascinating...

I'm wondering who was behind the disasters of 1857, now.

Probably Ronsend, because the overall effect appears to have been a split between the Northern and Southern Democrats, which would seem to send the industrialists into the arms of the Republican coalition...

Equally the editorials about the benefits of a Pacific Railroad, and the popular outrage at measures Frost would hate being vetoed...

The question is, will his cunning plan succeed?

I'm wondering who was behind the disasters of 1857, now.

Probably Ronsend, because the overall effect appears to have been a split between the Northern and Southern Democrats, which would seem to send the industrialists into the arms of the Republican coalition...

Equally the editorials about the benefits of a Pacific Railroad, and the popular outrage at measures Frost would hate being vetoed...

The question is, will his cunning plan succeed?

With the growth of railroad and the financial collapse, it appears the economic fortunes of America are turning into a colossus. But there is other business still at hand that must be settled...

On another note - one wonders what money was won or lost by our heroes and villains in the recent goings on. Here's to wishing Frost lost a bundle. But somehow I doubt it.

On another note - one wonders what money was won or lost by our heroes and villains in the recent goings on. Here's to wishing Frost lost a bundle. But somehow I doubt it.

The comment about the rope company reminds me of some modern companies which failed.

I was reading a history of the Supreme Court a few months ago and it was interesting how Taney lived long enough to see his most famous ruling nullified by the Civil War, and little longer.

I was reading a history of the Supreme Court a few months ago and it was interesting how Taney lived long enough to see his most famous ruling nullified by the Civil War, and little longer.

Very thought provoking, D. Interesting that 'bench legislation' will come into play in this arena a century early. I'm also intrigued at what effect on the expected coming war the early development of ironclads and a colonial army will have.

Vann

Vann

To all - the dates have been changed to protect the... um, the author?  - but the events are mostly historical. The Panic of 1857 did happen, and it was bad - it lingered until the Civil War. I'm pretty sure NE Rope had a historical counterpart in 1857 but I can't find my original source.

- but the events are mostly historical. The Panic of 1857 did happen, and it was bad - it lingered until the Civil War. I'm pretty sure NE Rope had a historical counterpart in 1857 but I can't find my original source.

Most 'men of finance' knew a contraction was possible in 1857 but they expectd it to be mild. With better economic models, computer power and foreknowledge of how events might turn out I'd be surprised if both sides weren't using the collapse to make piles of money and to get control of companies and securities cheaply.

Militarily the Union is stronger than it historically was, but it also has global commitments (Hispaniola and Madagascar). It is about to have even more...

One of the Republican talking points in 1858 and 1860 was the degree to which Democratic politicians pressured the Court to drop the hammer on slavery. There are letters from President Buchanan in which he urges Taney to write an opinion that will put an end to all the abolitionist furor.

But in the next episodes we will consider two cases before the Supreme Court, not one. And the rest of the depressing events of 1857-58.

Most 'men of finance' knew a contraction was possible in 1857 but they expectd it to be mild. With better economic models, computer power and foreknowledge of how events might turn out I'd be surprised if both sides weren't using the collapse to make piles of money and to get control of companies and securities cheaply.

Militarily the Union is stronger than it historically was, but it also has global commitments (Hispaniola and Madagascar). It is about to have even more...

One of the Republican talking points in 1858 and 1860 was the degree to which Democratic politicians pressured the Court to drop the hammer on slavery. There are letters from President Buchanan in which he urges Taney to write an opinion that will put an end to all the abolitionist furor.

But in the next episodes we will consider two cases before the Supreme Court, not one. And the rest of the depressing events of 1857-58.

Popular opinion seems to be increasingly radicalized and violent—and I imagine that the court’s ruling will make pouring gasoline on a fire seem conservative.

Caught up.

There is very much the impending sense of America hurtling - like a train with no breaks - towards some sort of catastrophe.

The appearance of Sam Clemens was nicely done. A very well written passage.

There is very much the impending sense of America hurtling - like a train with no breaks - towards some sort of catastrophe.

The appearance of Sam Clemens was nicely done. A very well written passage.

The collapsing economies of the United States and Britain, and to a lesser degree those of the continental European states, seized and held the attentions of the newspaper men of late 1857, and thereby the attention of the public at large. Such space as remained from lurid tales of bank collapses and business foreclosures was reserved for frightful, even barbaric, stories of the horrors unleashed by the Sepoy Mutiny in India. But these were not the only important events of the last half of the year, and the remainder perhaps deserve some note.

In 1839 the English adventurer James Brooke had arrived on the island of Borneo, aided the Sultan in thwarting a rebellion, and wound up the ‘White Rajah’ of Sarawak. His assassination in 1856 had opened the field to prospective claimants and rebels, for the Sultan possessed little power and few advisors of any ability. In September of 1856 one of the new pirate kings had taken the New England packet ‘Isaiah Pownall’ at cutlass-point and were holding out for a large ransom for ship and crew. After nearly a year of fruitless dickering the American Governor General of Madagascar Colony, John Mason of North Carolina, entrusted the resolution of the crisis to a pair of brisk young officers and dispatched a substantial force to overawe Sultan, pirate king and all.

In charge of the naval side of the operation was Captain Franklin Buchanan, a bluff, capable and hard-headed Marylander. His force consisted of the ships of the line ‘North Carolina’ and the older and less-satisfactory ‘Columbus’, and two frigates. The first of these was the ‘Independence’, originally a sister-ship to ‘Columbus’. Having proven badly-designed and being very much overweight, she was cut down into a gigantic frigate by having her upper gun-deck removed. With her broad beam, lighter weight and original liner-sized masts and spars, not to mention the massive 32-pounder cannon in her broadside, she was one of the fastest and most powerful frigates in any navy. The other frigate was virtually brand-new, having been launched in 1842, and was of the most modern design for a sailing warship. In keeping with the American tradition of naming frigates for rivers, she was christened, ‘Cumberland’. Several small steamers and a number of transports completed the little armada.

The land forces of the punitive expedition consisted of a single division of Creoles recruited from Hispaniola, reinforced by a brigade of elite troops, the Cap-Haitien Guards, commanded by William W Harmon. Harmon was one of the few American officers of high rank who had not attended West Point, and his assignment to the Creole division shows he was without the political pull necessary to obtain a more prestigious position. In his letters home, Harmon would reveal he was spoiling for a fight, eager to make a name for himself and earn a command closer to home.

The squadron hove to off the city of Sarawak (formerly and latterly Kuching) in late October of 1857 in the midst of yet another coup attempt. Unsettled political conditions due to Brooke’s assassination and the ongoing mutiny in India had led to a seemingly endless series of coups and incursions, and the arrival of such a large and powerful squadron drove apprehensions to new heights. On the day after the Americans arrived a fort began booming out a salute – or so they thought, until one cannonball skipped the surface a few yards from the bow of the ‘Columbus’. Incensed, Flag Officer Buchanan ordered the troops landed at once. In short order the Creoles turned out the malcontents from the city streets and the remnants of Brooke’s old army surrendered the forts.

An exchange of diplomatic notes led nowhere; the British protested, the Sultan dithered and the pirates and rebels continued to run amok. By hard-marching and use of the squadron’s command of the sea, Harmon managed to cross the Rajang River and reach Sibu ahead of the Sultan’s army. The latter moved cautiously up the Igan River from Mukah and Oya, as the thick foliage, soggy ground and non-existent roads made movement along the rivers difficult and travel overland impossible. Thinking to achieve surprise, the Sultan launched an all-out assault on Christmas Day, only to have the attack shattered by modern firearms. As the Sultan’s army routed, Harmon’s Creoles charged them with bayonets, following up the resounding victory with a combined sea-born and overland movement on Brunei itself. By March of 1858 the entire west coast of Borneo had been pacified and the remaining crew of the ‘Isaiah Pownall’ rescued from the Sultan’s prison. Negotiations would continue through September of that year, complicated by the death of Mason at Madagascar, Harmon’s contraction of malaria and a succession crisis in the Sultan’s court. At last even the British agreed that something had to be done about the pirates and rebels of ‘wild, wild Borneo’ and so the territory was officially made an American Colony in December.

Meanwhile, the Reform elements that had ascended to power in Mexico were finding their attempts to curtail the powers of the Church were met with enthusiasm – and vociferous resistance. Led by the capable Benito Juarez, the Reformists managed to hold out against the first coup attempt, but the second, in November of 1857, sent them flying to Vera Cruz, where they set up a rival government to the conservative faction in Mexico City. Knowing that Juarez was pro-American and the conservative ‘Lords of the Haciendas’ wanted nothing more than to recover the lands lost in the Mexican War, the Bright government provided some funds and assistance to the Reformists but otherwise kept out of the quarrel.

That administration certainly had its hands full with domestic issues and could in truth not spare the time and attention for intervention in Mexico, even had they been so inclined. For in March of 1857 the Supreme Court issued its opinion in the case of Dred Scott v Sandford, and in the next month it delivered another on Lemmon v The People of New York. Both cases involved slavery, and in both the Democrats hoped to finally settle the issue so far as the law and the Constitution would allow.

In brief, Dred Scott was a slave belonging to Dr John Emerson, who was in the Army and thus often transferred. At various times he resided in Illinois, a free state, and in Minnesota, then a part of the Wisconsin Territory and a free territory by virtue of the old Northwest Ordinance and the Missouri Compromise. On these grounds and others, Scott sued for his freedom in 1846. The case traveled a torturous path through Missouri state courts and was appealed to the Supreme Court. Pressure was brought to have the case delayed until after the presidential election and delivered before the inauguration in March. Chief Justice Roger Taney evidently agreed, for the majority decision was read out three days before Bright’s inauguration on March 4th.

The court could have simply found that, as a slave, Scott had no right to sue in his own behalf, and many – including two justices of the court – expected it to do no more than that. But Taney went on for page after page, first holding that Negroes were, "beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race, either in social or political relations, and so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect." Further, the Court held that a slave carried to a territory would not thereby be freed because Congress had not the power to forbid slavery in the territories. The Fifth Amendment, said the Court, prohibited any law that would deprive a citizen of property merely because he went into a territory. Further, the Court stated that no territorial government had the right to ban slavery.

In October of 1852, two citizens of Virginia, Jonathan and Juliet Lemmon, traveled to New York City in company with her servants, intending to take passage on a steamship to Texas as soon as passage could be arranged. But a free black man of that city, observing the situation, petitioned a judge for a writ of habeas corpus on the grounds that, as New York state law forbade slavery, the servants were now free, to wit: "No person held as a slave shall be imported, introduced, or brought into this State, on any pretence whatever. Every such person shall be free." And, "Every person brought into this State as a slave shall be free."

The State of Virginia immediately undertook to assemble a crack legal team for the appeal, while the State of New York was ably represented by Chester A Arthur. This case, too, found its way through the state courts and was accelerated to the Supreme Court by pleas from prominent men throughout the Southern states. Building and expanding upon the previous Dred Scott decision the Court found the New York law invalid. The mere act of crossing a state line could not free a slave. The regulation of interstate commerce was reserved to the federal Congress, and the ‘full faith and credit’ clause required New York to respect Virginia law in this case. In short, the Court held, a slave owner might take his property into any state or territory, for any length of time, and no territorial or state government could do anything to stop him.

It would not be too extreme to characterize the reaction in the North to these decisions as pyrotechnical. Overnight the ranks of the Republican Party swelled. Even heretofore staunch Democrats abandoned the cause. “I am gone from the Party, or rather the Party has gone from me,” one wrote to a friend. “Hold no place for me; I shall not return.” In the Southern states the mood was jubilant, triumphant, and the tone of the newspaper articles and public speeches was one of gloating satisfaction. “The Abolitionists and Black Republicans are dead, dead, dead,” Senator Jefferson Davis of Mississippi opined. His funereal proclamation was a bit premature. In the by-year elections of 1858 the Democratic candidates were virtually swept from the previously solid states of New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Delaware. Maryland trembled upon the brink but narrowly elected a Democratic majority in its state houses; the new governor was a Know-Nothing, however, and a Republican in all but name. The border states of Kentucky and Tennessee were riven by bloody violence, particularly in Louisville and Knoxville. Both remained in the Democratic camp, but the governor of Kentucky (not up for re-election until 1859) was already a Republican-leaning Know-Nothing. Missouri, despite repeated bloody riots, went solidly Republican due to the large number of anti-slavery votes cast by German immigrants in St Louis.

In Washington, President Bright had invited some political intimates and their wives to an election-eve get-together. As the results came in from the telegraph in the nearby War Department, one attendee noted, “We drank toasts to our losses and laughed at our defeats until our tears ran… so absolute was our destruction that no other response was possible.” In every election above the Mason-Dixon Line, and in a few below it, the new Republican Party had made sweeping gains. There was, however one notable exception: in Illinois, where Stephen Douglas intended to be returned to his seat in the US Senate.

Senate seats, in those days, were not filled by popular election. In most states the state legislature (or even merely the state Senate) would elect the men to represent the interests of the state government in Washington. By campaigning, a candidate might hope to get representatives and senators of his own party elected to the state legislature and thus ensure his own selection to the national office. Douglas’s six-year term was up, and as he desired to return to his senatorial office, he was stumping across the state giving rousing orations in dozens of little Illinois towns. Along the way he acquired a competitor, someone well known if not previously very successful in Illinois politics. A Springfield lawyer named Abraham Lincoln had been so moved by the Kansas-Nebraska Acts and the recent Court decisions that he had decided to follow Douglas around, giving his own speech in each town a day or so after Douglas had moved on. Quickly it occurred to both that their interests would best be served by a series of head-to-head debates, one in each of the seven districts Douglas had not yet visited. Although he had the most at stake, Douglas believed his powers of oratory would carry the day, for he and Lincoln were acquaintances and opponents of long standing in Illinois politics.

Because of Douglas’ national reputation and his role in crafting the Kansas-Nebraska Acts the debates were covered by reporters from many of the newspapers of the big cities: Chicago, Philadelphia, Boston, and even New York. As far as their effect on the state elections, the debates were a draw. Enough Democrats remained in the Illinois Senate, and just a few legislators had problems with Lincoln personally, and so Douglas’ re-election was a certainty. But the Northern press faithfully reported the speeches, and the Northern readers went wild for Lincoln. His calm, measured prose and clearly reasoned arguments gave voice to anti-slavery feelings in a way no-one else had done to date. Overnight, Lincoln Clubs and Corresponding Societies sprang up across the Western and Northern states. Although deeply depressed after his defeat, Lincoln found his spirits revived by the cascade of letters and telegrams that praised and congratulated him. Along with these came offers of speaking engagements, but as Lincoln felt no strong desire to become an orator – nor did he believe he had any special talent for it – he politely declined them all.

And so the nation staggered on, through the elections of 1858 and into the dark new day of 1859. Whatever else might be said, it was universally recognized that the United States had become a Republic run by – and for – the slaveholding powers of the South. But even the elections of 1858 did nothing to convince the Southern men that the North could, or would, do anything about the situation. In every test of wills so far, and in every Presidential election of modern times, the threat of secession had served to bring the North to heel. One man did clearly see the course that history might take, though he had but one working eye. His name was Jefferson Davis, Senator from Mississippi. In a letter to the governor of that state, he wrote, “The arithmetic is against us, absolutely. Without the lower northern states, and without the absolute loyalty of the border men, we will be overthrown, our property confiscated and our rights set at naught. We must make provision now… in the crisis, only independence will do.”

In 1839 the English adventurer James Brooke had arrived on the island of Borneo, aided the Sultan in thwarting a rebellion, and wound up the ‘White Rajah’ of Sarawak. His assassination in 1856 had opened the field to prospective claimants and rebels, for the Sultan possessed little power and few advisors of any ability. In September of 1856 one of the new pirate kings had taken the New England packet ‘Isaiah Pownall’ at cutlass-point and were holding out for a large ransom for ship and crew. After nearly a year of fruitless dickering the American Governor General of Madagascar Colony, John Mason of North Carolina, entrusted the resolution of the crisis to a pair of brisk young officers and dispatched a substantial force to overawe Sultan, pirate king and all.

In charge of the naval side of the operation was Captain Franklin Buchanan, a bluff, capable and hard-headed Marylander. His force consisted of the ships of the line ‘North Carolina’ and the older and less-satisfactory ‘Columbus’, and two frigates. The first of these was the ‘Independence’, originally a sister-ship to ‘Columbus’. Having proven badly-designed and being very much overweight, she was cut down into a gigantic frigate by having her upper gun-deck removed. With her broad beam, lighter weight and original liner-sized masts and spars, not to mention the massive 32-pounder cannon in her broadside, she was one of the fastest and most powerful frigates in any navy. The other frigate was virtually brand-new, having been launched in 1842, and was of the most modern design for a sailing warship. In keeping with the American tradition of naming frigates for rivers, she was christened, ‘Cumberland’. Several small steamers and a number of transports completed the little armada.

The land forces of the punitive expedition consisted of a single division of Creoles recruited from Hispaniola, reinforced by a brigade of elite troops, the Cap-Haitien Guards, commanded by William W Harmon. Harmon was one of the few American officers of high rank who had not attended West Point, and his assignment to the Creole division shows he was without the political pull necessary to obtain a more prestigious position. In his letters home, Harmon would reveal he was spoiling for a fight, eager to make a name for himself and earn a command closer to home.

The squadron hove to off the city of Sarawak (formerly and latterly Kuching) in late October of 1857 in the midst of yet another coup attempt. Unsettled political conditions due to Brooke’s assassination and the ongoing mutiny in India had led to a seemingly endless series of coups and incursions, and the arrival of such a large and powerful squadron drove apprehensions to new heights. On the day after the Americans arrived a fort began booming out a salute – or so they thought, until one cannonball skipped the surface a few yards from the bow of the ‘Columbus’. Incensed, Flag Officer Buchanan ordered the troops landed at once. In short order the Creoles turned out the malcontents from the city streets and the remnants of Brooke’s old army surrendered the forts.

An exchange of diplomatic notes led nowhere; the British protested, the Sultan dithered and the pirates and rebels continued to run amok. By hard-marching and use of the squadron’s command of the sea, Harmon managed to cross the Rajang River and reach Sibu ahead of the Sultan’s army. The latter moved cautiously up the Igan River from Mukah and Oya, as the thick foliage, soggy ground and non-existent roads made movement along the rivers difficult and travel overland impossible. Thinking to achieve surprise, the Sultan launched an all-out assault on Christmas Day, only to have the attack shattered by modern firearms. As the Sultan’s army routed, Harmon’s Creoles charged them with bayonets, following up the resounding victory with a combined sea-born and overland movement on Brunei itself. By March of 1858 the entire west coast of Borneo had been pacified and the remaining crew of the ‘Isaiah Pownall’ rescued from the Sultan’s prison. Negotiations would continue through September of that year, complicated by the death of Mason at Madagascar, Harmon’s contraction of malaria and a succession crisis in the Sultan’s court. At last even the British agreed that something had to be done about the pirates and rebels of ‘wild, wild Borneo’ and so the territory was officially made an American Colony in December.

Meanwhile, the Reform elements that had ascended to power in Mexico were finding their attempts to curtail the powers of the Church were met with enthusiasm – and vociferous resistance. Led by the capable Benito Juarez, the Reformists managed to hold out against the first coup attempt, but the second, in November of 1857, sent them flying to Vera Cruz, where they set up a rival government to the conservative faction in Mexico City. Knowing that Juarez was pro-American and the conservative ‘Lords of the Haciendas’ wanted nothing more than to recover the lands lost in the Mexican War, the Bright government provided some funds and assistance to the Reformists but otherwise kept out of the quarrel.

That administration certainly had its hands full with domestic issues and could in truth not spare the time and attention for intervention in Mexico, even had they been so inclined. For in March of 1857 the Supreme Court issued its opinion in the case of Dred Scott v Sandford, and in the next month it delivered another on Lemmon v The People of New York. Both cases involved slavery, and in both the Democrats hoped to finally settle the issue so far as the law and the Constitution would allow.

In brief, Dred Scott was a slave belonging to Dr John Emerson, who was in the Army and thus often transferred. At various times he resided in Illinois, a free state, and in Minnesota, then a part of the Wisconsin Territory and a free territory by virtue of the old Northwest Ordinance and the Missouri Compromise. On these grounds and others, Scott sued for his freedom in 1846. The case traveled a torturous path through Missouri state courts and was appealed to the Supreme Court. Pressure was brought to have the case delayed until after the presidential election and delivered before the inauguration in March. Chief Justice Roger Taney evidently agreed, for the majority decision was read out three days before Bright’s inauguration on March 4th.

The court could have simply found that, as a slave, Scott had no right to sue in his own behalf, and many – including two justices of the court – expected it to do no more than that. But Taney went on for page after page, first holding that Negroes were, "beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race, either in social or political relations, and so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect." Further, the Court held that a slave carried to a territory would not thereby be freed because Congress had not the power to forbid slavery in the territories. The Fifth Amendment, said the Court, prohibited any law that would deprive a citizen of property merely because he went into a territory. Further, the Court stated that no territorial government had the right to ban slavery.

In October of 1852, two citizens of Virginia, Jonathan and Juliet Lemmon, traveled to New York City in company with her servants, intending to take passage on a steamship to Texas as soon as passage could be arranged. But a free black man of that city, observing the situation, petitioned a judge for a writ of habeas corpus on the grounds that, as New York state law forbade slavery, the servants were now free, to wit: "No person held as a slave shall be imported, introduced, or brought into this State, on any pretence whatever. Every such person shall be free." And, "Every person brought into this State as a slave shall be free."

The State of Virginia immediately undertook to assemble a crack legal team for the appeal, while the State of New York was ably represented by Chester A Arthur. This case, too, found its way through the state courts and was accelerated to the Supreme Court by pleas from prominent men throughout the Southern states. Building and expanding upon the previous Dred Scott decision the Court found the New York law invalid. The mere act of crossing a state line could not free a slave. The regulation of interstate commerce was reserved to the federal Congress, and the ‘full faith and credit’ clause required New York to respect Virginia law in this case. In short, the Court held, a slave owner might take his property into any state or territory, for any length of time, and no territorial or state government could do anything to stop him.

It would not be too extreme to characterize the reaction in the North to these decisions as pyrotechnical. Overnight the ranks of the Republican Party swelled. Even heretofore staunch Democrats abandoned the cause. “I am gone from the Party, or rather the Party has gone from me,” one wrote to a friend. “Hold no place for me; I shall not return.” In the Southern states the mood was jubilant, triumphant, and the tone of the newspaper articles and public speeches was one of gloating satisfaction. “The Abolitionists and Black Republicans are dead, dead, dead,” Senator Jefferson Davis of Mississippi opined. His funereal proclamation was a bit premature. In the by-year elections of 1858 the Democratic candidates were virtually swept from the previously solid states of New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Delaware. Maryland trembled upon the brink but narrowly elected a Democratic majority in its state houses; the new governor was a Know-Nothing, however, and a Republican in all but name. The border states of Kentucky and Tennessee were riven by bloody violence, particularly in Louisville and Knoxville. Both remained in the Democratic camp, but the governor of Kentucky (not up for re-election until 1859) was already a Republican-leaning Know-Nothing. Missouri, despite repeated bloody riots, went solidly Republican due to the large number of anti-slavery votes cast by German immigrants in St Louis.

In Washington, President Bright had invited some political intimates and their wives to an election-eve get-together. As the results came in from the telegraph in the nearby War Department, one attendee noted, “We drank toasts to our losses and laughed at our defeats until our tears ran… so absolute was our destruction that no other response was possible.” In every election above the Mason-Dixon Line, and in a few below it, the new Republican Party had made sweeping gains. There was, however one notable exception: in Illinois, where Stephen Douglas intended to be returned to his seat in the US Senate.

Senate seats, in those days, were not filled by popular election. In most states the state legislature (or even merely the state Senate) would elect the men to represent the interests of the state government in Washington. By campaigning, a candidate might hope to get representatives and senators of his own party elected to the state legislature and thus ensure his own selection to the national office. Douglas’s six-year term was up, and as he desired to return to his senatorial office, he was stumping across the state giving rousing orations in dozens of little Illinois towns. Along the way he acquired a competitor, someone well known if not previously very successful in Illinois politics. A Springfield lawyer named Abraham Lincoln had been so moved by the Kansas-Nebraska Acts and the recent Court decisions that he had decided to follow Douglas around, giving his own speech in each town a day or so after Douglas had moved on. Quickly it occurred to both that their interests would best be served by a series of head-to-head debates, one in each of the seven districts Douglas had not yet visited. Although he had the most at stake, Douglas believed his powers of oratory would carry the day, for he and Lincoln were acquaintances and opponents of long standing in Illinois politics.

Because of Douglas’ national reputation and his role in crafting the Kansas-Nebraska Acts the debates were covered by reporters from many of the newspapers of the big cities: Chicago, Philadelphia, Boston, and even New York. As far as their effect on the state elections, the debates were a draw. Enough Democrats remained in the Illinois Senate, and just a few legislators had problems with Lincoln personally, and so Douglas’ re-election was a certainty. But the Northern press faithfully reported the speeches, and the Northern readers went wild for Lincoln. His calm, measured prose and clearly reasoned arguments gave voice to anti-slavery feelings in a way no-one else had done to date. Overnight, Lincoln Clubs and Corresponding Societies sprang up across the Western and Northern states. Although deeply depressed after his defeat, Lincoln found his spirits revived by the cascade of letters and telegrams that praised and congratulated him. Along with these came offers of speaking engagements, but as Lincoln felt no strong desire to become an orator – nor did he believe he had any special talent for it – he politely declined them all.

And so the nation staggered on, through the elections of 1858 and into the dark new day of 1859. Whatever else might be said, it was universally recognized that the United States had become a Republic run by – and for – the slaveholding powers of the South. But even the elections of 1858 did nothing to convince the Southern men that the North could, or would, do anything about the situation. In every test of wills so far, and in every Presidential election of modern times, the threat of secession had served to bring the North to heel. One man did clearly see the course that history might take, though he had but one working eye. His name was Jefferson Davis, Senator from Mississippi. In a letter to the governor of that state, he wrote, “The arithmetic is against us, absolutely. Without the lower northern states, and without the absolute loyalty of the border men, we will be overthrown, our property confiscated and our rights set at naught. We must make provision now… in the crisis, only independence will do.”

Last edited:

Fulcrumvale - You would be correct about the violence and increasing savagery of the responses This is going to be a battle to the death.

'Dred Scott' is historical; 'Lemmon' would have come before the court in 1860 had secession not rendered it moot.

At long last the people of the North are stirring... perhaps too late?

stnylan - Good to have you back! I have certainly missed you!

This is such a BIG canvas... the sheer number of really important men in the US alone is staggering, not to mention the UK, France, Prussia... And the things that are going on, all over the globe, are so numerous and significant it is hard to keep track.

I have another day off on Thursday. With any luck we'll move a major step forward then. Sorry for the long, dense passages... but that probably won't change for a while.

'Dred Scott' is historical; 'Lemmon' would have come before the court in 1860 had secession not rendered it moot.

At long last the people of the North are stirring... perhaps too late?

stnylan - Good to have you back! I have certainly missed you!

This is such a BIG canvas... the sheer number of really important men in the US alone is staggering, not to mention the UK, France, Prussia... And the things that are going on, all over the globe, are so numerous and significant it is hard to keep track.

I have another day off on Thursday. With any luck we'll move a major step forward then. Sorry for the long, dense passages... but that probably won't change for a while.

To carry on my previous analogy - it appears the hurtling train is just now trying to take a hairpin bend, and its wheels cannot yet decide whether to stay on the rails or not.

The image of toasting defeats is another nice touch. There is a touch of Hitler in his bunker about it - of a place where reality and perception start to separate.

The image of toasting defeats is another nice touch. There is a touch of Hitler in his bunker about it - of a place where reality and perception start to separate.

I seem to recall reading about Lemmon somewhere, although as it did not get to the court it obviously isn't as famous as Scott.

Interesting little escapade off in the Indies.

Interesting little escapade off in the Indies.

Two updates this week!

Hurrah for dense text!

Also, a toast to the growth of the Republican party...may it live long and prosper (for a few years).

So, the specter of secession and civil war looms large, well nigh inescapable. Perhaps the following words express my feelings about it best.

The Almighty has his own purposes. "Woe unto the world because of offenses! for it must needs be that offenses come; but woe to that man by whom the offense cometh." If we shall suppose that American slavery is one of those offenses which, in the providence of God, must needs come, but which, having continued through his appointed time, he now wills to remove, and that he gives to both North and South this terrible war, as the woe due to those by whom the offense came, shall we discern therein any departure from those divine attributes which the believers in a living God always ascribe to him? Fondly do we hope--fervently do we pray--that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman's two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn by the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said, "The judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether."

Thanks D!

TheExecuter

Hurrah for dense text!

Also, a toast to the growth of the Republican party...may it live long and prosper (for a few years).

So, the specter of secession and civil war looms large, well nigh inescapable. Perhaps the following words express my feelings about it best.