I think the reaons were convincing but I also think that if I had been around at the time I would have considered being the assassin. There are a few historical points about which I can get my hackles up and now I am getting them up over a fictional rendition of history.

A Special Providence

- Thread starter Director

- Start date

-

We have updated our Community Code of Conduct. Please read through the new rules for the forum that are an integral part of Paradox Interactive’s User Agreement.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Don’t even go there. The Union has to have some victories before the war starts…stnylan said:The dis-satisfaction of New England seems ominous.

I particularly liked the 'impeachment' update...the pacing of it was perfect. I even found myself a bit excited as the right honorable representative from Pennsylvania called for impeachment. That said, I probably would have voted it down...there not being enough evidence of treasonable activities in my view to actually impeach. Censure yes, impeach...tad too strong for my taste. So...you convinced me! I took the liberty of imagining the roar of the house of commons during appropriate sections of the update...hope your not offended!

TheExecuter

TheExecuter

Given that there is trouble out west, trouble down south, I would not at all be surprised if there is also trouble in the north-east.Fulcrumvale said:Don’t even go there. The Union has to have some victories before the war starts…

For a number of reasons, each in themselves fairly small but together fairly large, Abe Lincoln has a task considerably more difficult than the one that confronted him in real life.

Well, gee, things don't look at all to be, ah, welcoming for good ol' Abe, do they? We have issues in the South, possible problems in the West, and New England in the Northeast grumbling. And you question why I'm so concerned with the miltiary, D?

While I know Abe would much prefer for the 'wayward sisters’ to return to the fold on their own, but I dearly hope that he has at least begun to sound out the Army to see where it stands. There are times, and sadly it looks like this is rapidly becoming one, that the only thing that can actually prevent the descent into civil war is a nation's military. Unless the military itself is fractured.

While I know Abe would much prefer for the 'wayward sisters’ to return to the fold on their own, but I dearly hope that he has at least begun to sound out the Army to see where it stands. There are times, and sadly it looks like this is rapidly becoming one, that the only thing that can actually prevent the descent into civil war is a nation's military. Unless the military itself is fractured.

Director: ...Ahead lay… what? No one in America could have answered the question with any assurance, but every American knew that things had changed.

aye, things ain't what they used to be ! !

it seems to me that Frost wins either way. a split US or a Confederate victory. the alternative of a US victory seems somewhat unlikely...

really, the US victory would hinge on the military.

awesome update ! !

if i am able, i will clear a PM spot for ya, D.

aye, things ain't what they used to be ! !

it seems to me that Frost wins either way. a split US or a Confederate victory. the alternative of a US victory seems somewhat unlikely...

really, the US victory would hinge on the military.

awesome update ! !

if i am able, i will clear a PM spot for ya, D.

My, my - things have certainly sped up here. Toombs as President, Bright survives to do nothing for another day and now Lincoln arrives. What will his hand be in this game? He's holding firm and has kept his best poker face but he'll soon have to lay down his cards and show them to all.

In the new Confederacy the Provisional Congress continued in session in Montgomery while President Toombs departed to set up new government offices in Columbia. His journey became a festive event with his special train stopping at every town for celebrations, patriotic flourishes and of course speeches. Along with the bouncy strains of ‘Bonnie Blue Flag’ and the minstrel plunking of ‘Dixie’, the marching beat of a new song rang out:

“There’s a new star tonight in the Southern sky,

Shining bright for all the world to see!

Yes, a brave new star for a grand new land,

A Southern Confed-ra-cy!”

As exhausting as the travel must have been, Toombs undoubtedly enjoyed the celebrations and the admiring attention showered on him at every stop. His arrival in Columbia meant an end to the parade of well-wishers, replaced by a host bearing news of serious problems ahead. Instead of men who were eager to shake his hand the new President was beset by men who wanted jobs, favors or contracts. And Columbia, while a pleasant enough city, soon revealed itself unready to take on the new role as capital of an infant nation. The state government had offered the use of its facilities as an interim measure, but the sad truth was that the state had little to offer. The new statehouse, a-building since 1851, was still no more than a pile of masonry, marble, lawsuits and accusations; state officials were conducting their business in converted warehouses, rented rooms and the like. The new Confederate government had no money, little credit and lacked the officers who could oversee the construction of the new buildings that would be required. For the moment, Toombs telegraphed, the Congress must continue to meet in Montgomery. Above all, he stressed, he must have funds, and secondly he must have expert engineering assistance.

Scratching away at his writing desk in a suite at the newly renamed Confederate Hotel, Toombs wrestled first with the task of filling out his cabinet. No state could be excluded from the cabinet, which conveniently would have six positions, but other considerations were also in play. The President was a Georgian, the Vice-President was from Louisiana and the capital was to be in South Carolina. Clearly, in order that the more populous states should not seem to exert an undue share of influence, Mississippi, Alabama and Florida must be honored with appointments to the highest available offices. The new President was a moderate, as were all his close friends and allies. They believed it was essential to their chances of attracting the other Southern states that the new government be seen to be in the hands of moderates and not radicals and ‘fire-eaters’. Unstated was the assumption that a moderate, conservative government that based its case on states’ rights would be more appealing to foreign governments than a ‘fire-eating’, pro-slavery one. In order of importance, the six cabinet offices would be State, Treasury, War, Justice, Navy and the Post. War must go to Jefferson Davis, should he be well enough to accept it; Davis had been an exceptional Secretary in the Pierce administration and would be a popular choice, as well as a fulfillment of the obligation to Mississippi. The Navy could be offered to Stephen Mallory of Florida, who had extensive experience in naval and maritime affairs. The State Department must go to an Alabamian, and as William Yancey was too ‘ultra’ and too ill besides, the lesser-known Jabez Curry would receive the nod. Treasury must go to Memminger or Trenholm of South Carolina as they were the closest to financial experts that the South could offer. That left Judah Benjamin of Louisiana for Attorney General, a post for which the affable and talented man from New Orleans was perhaps not well suited, but a man of his talents must be gotten into the administration somehow. Having disposed of the major offices, Toombs proposed to offer the Postmaster’s hat to fatherly Robert Barnwell of South Carolina. He would have liked to have his good friend Alexander Stephens in the Cabinet as well, but would content himself with having a sure ally in the Congress instead.

And what of Howell Cobb, whose dreams of the Presidency had been shattered, and his brother Thomas, whose ambitions had been transparent enough to be the subject of scorn and derision from the other delegates? Howell was named presiding officer of the Provisional Congress and had done a competent if not inspiring job. His revelation of the contents of Bright’s letter had been calculated to vault him to the front-runner’s position for the Presidency, but other delegates had more accurately assessed the import of the news. Bright had only a short time remaining in office, they noted, and the reaction of the Northern public to Bright’s proposals was unlikely to be kind. Consequently, they reasoned, the best way to make use of Howell Cobb’s influence with Bright – and to remove his interference with their own presidential hopes – was to send him to Washington, post-haste, as a negotiator and advocate for the new Confederacy. Cobb must have known it was a form of political exile, but he was patriot enough to take up the task as directed. Before he could arrive in Washington the storm had well and truly broken; Bright was on trial for treason and was under virtual house arrest, certainly unable to see an ambassador from the rebellious states. Doubly crushed, Cobb returned to Montgomery and took up his former post as presiding officer, well aware that his old enemy Toombs would have no position in the administration for him. His brother Tom had also taken the temper of the proceedings and found the prospects for advancement sour. Declaring that he would not accept a Cabinet position below State, and perhaps not even that, Tom Cobb had put on his white gloves and boarded the train for Georgia.

The Provisional Congress could and did enact a sum of fiat money, essentially promissory notes to state banks, to be redeemed when the country was able to collect taxes and tariffs. An issue of bonds was eagerly subscribed by wealthy planters, and for the moment the new republic was equipped with credit necessary for its needs. The most pressing of those needs was the establishment of a national army to regularize and supplement the militias of the various states. The Yankees were not thought to be a serious threat in the short term – in Lincoln’s inaugural address he had promised to ‘suspend’ federal activities in the rebellious states ‘for a time’ – but everyone thought it was better to be safee than sorry. The arrival of P G T Beauregard in Columbia proved fortuitous as it enabled Toombs to unload most of the organizational work of the new army onto the Creole’s shoulders. The Secretary of War would be fully occupied with the setting up of the administrative and logistical elements of the service, in particular the supply of weapons, gunpowder, uniforms and rations. Most of this would have to come from foreign sources, until or unless the Confederacy could develop its own resources. Beauregard’s advice was frequently also sought on matters such as the construction of coastal fortifications and the design of a new national capitol, intended to grace the high ground to the east of the city.

In the North, Lincoln had likewise settled his Cabinet. Most of the hard choices had been made after his nomination, for the new President was determined to staff his administration with as many capable men of the new Republican Party as possible, and with as many Democrats as could be persuaded to join. To William Seward of New York, the elder statesman of the young Party, must go the most prestigious post: the State Department. Salmon Chase of Ohio would take the Treasury, though Seward did not want him in the Cabinet at all. Montgomery Blair from the critical state of Missouri would receive the War Department; Simon Cameron of Pennsylvania had coveted the Treasury, or the War office as a lesser prize, but the odor of corruption that clung to him made his confirmation impossible. He was instead sent to be Minister to France, disgruntled but unable to find anyone in the Party to take his side. Lincoln’s most surprising choice was to offer to bring in his old opponent Stephen Douglas as Attorney General. Dispirited and in ill-health, Douglas at first refused, but Lincoln tendered the offer a second time and Douglas agreed for the sake of national unity. Democrat Edwin Stanton would continue as Secretary of the Interior, having served in that capacity in the last days of the ‘dead duck’ Bright administration. Gideon Welles of Connecticut was a popular choice to head the Navy, and Edward Bates of the key state of Maryland would be Postmaster.

With the dead hand of the Bright administration removed the Congress, less the members from the seceded states, remained in session and strove diligently to produce a compromise that would bring the errant Southern states back into the Union. Taking their cue from Lincoln, Republicans participated in these discussions while remaining skeptical of any chance of success. “Let us not impede these discussions, if a compromise can be had without our giving up any of the critical points on which the administration was elected,” one Washington newspaper editor urged. “But let us make no shameful peace.” And so began the period of ‘watchful waiting’, or ‘masterly inactivity’, the North refusing to offer provocation and the Upper South refusing to secede without cause. Delegations from the Confederacy visited the Border and Upper South, but to no immediate avail. The men of those states who favored secession were a minority, and lacked the influence to carry their states out of the Union.

That did not mean the Lincoln administration was wholly idle, for supplementary appropriations were immediately necessary for the expansion of the Army and Navy, and for bringing the state militias to a higher standard of readiness. To Democrats who denounced these measures as ‘provocative’ and ‘infamous’, Lincoln merely replied that the Southern states were rapidly recruiting a large army, and that while he proposed no invasion at this time, to see to the national defense was only prudent. Pursuant to this, Lincoln was meeting on April 1st with the principal members of his military team, Secretary Blair, General of the Army Winfield Scott and the Commandant of Cadets at West Point, W T Sherman, when word arrived by telegraph that an armed gang had descended upon the little town of Harpers Ferry in western Virginia. Then the telegraph had gone dead, presumably cut by the invaders.

At that time, Harpers Ferry was a small town of only modest importance. Water power from the Shenandoah and Potomac Rivers had been its original reason for existence, but transportation along the Potomac canal was limited, and steam power had made water power of limited utility. Then the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad had come, riding the same gaps in the mountains that allowed the Potomac River to pass, and Harpers Ferry had gained a new lease on life as a way-station between the Ohio River valley and the great cities of the east. Through it all there had been the federal arsenal, a complex of buildings that used water power to shape gun butts, drill rifle barrels and carry out the hundreds of mechanical operations necessary to make small arms. It was for this stock of over 100,000 rifles and muskets, and for the gunpowder and ammunition stored nearby, that the raiders had come.

John Brown

As the world would soon know, their leader was a man named John Brown. A fervent abolitionist, Brown had taken his own advice to direct action in Kansas, killing at least eight pro-slavery farmers. As Lincoln’s election came and as the six Southern states went out of the Union, Brown had joined his voice to that of prominent New England men to urge immediate, direct action. Disgusted with Lincoln’s cautious, pragmatic policy, Brown had embarked on a speaking tour designed to raise money for a bold stroke, a move he predicted would electrify the nation. His exact intentions were disclosed to only a very few: John Brown would seize the arsenal, arm the slaves and raise the region in revolt.

Any sober contemplation would have revealed dozens of flaws, any one of which would serve to doom the plan outright. But if Brown’s plans were faulty his righteous indignation convinced his supporters to fund, equip and in some cases to join his tiny band. No more than thirty men marched over the railroad bridge in the early morning hours of April 1st, and few of them had any practical knowledge of military matters. Whatever plan Brown might have had went by the wayside when a night watchman put a bullet into Brown’s son, Watson. In the melee that followed, Brown’s supporters torched the better part of the town and retreated into the arsenal works to await the slaves they confidently expected to flock to their standard.

In mid-morning a B&O train was fired upon as it neared the Harpers Ferry station, probably by angry residents who had taken up positions on the heights around the town from which they could pepper the thick masonry walls of the arsenal. The engineer was wounded but managed to open the throttle and speed past, sending out an alert from the next stop. This telegraph was received at the War Department and forwarded to the White House in mid-morning of April 1st where it was read with amazement by President Lincoln and General Winfield Scott. After only a few minutes of deliberation it was settled that Colonels Sherman and Grant would take charge of any troops available in the Washington area and proceed at once to the site.

“There’s a new star tonight in the Southern sky,

Shining bright for all the world to see!

Yes, a brave new star for a grand new land,

A Southern Confed-ra-cy!”

As exhausting as the travel must have been, Toombs undoubtedly enjoyed the celebrations and the admiring attention showered on him at every stop. His arrival in Columbia meant an end to the parade of well-wishers, replaced by a host bearing news of serious problems ahead. Instead of men who were eager to shake his hand the new President was beset by men who wanted jobs, favors or contracts. And Columbia, while a pleasant enough city, soon revealed itself unready to take on the new role as capital of an infant nation. The state government had offered the use of its facilities as an interim measure, but the sad truth was that the state had little to offer. The new statehouse, a-building since 1851, was still no more than a pile of masonry, marble, lawsuits and accusations; state officials were conducting their business in converted warehouses, rented rooms and the like. The new Confederate government had no money, little credit and lacked the officers who could oversee the construction of the new buildings that would be required. For the moment, Toombs telegraphed, the Congress must continue to meet in Montgomery. Above all, he stressed, he must have funds, and secondly he must have expert engineering assistance.

Scratching away at his writing desk in a suite at the newly renamed Confederate Hotel, Toombs wrestled first with the task of filling out his cabinet. No state could be excluded from the cabinet, which conveniently would have six positions, but other considerations were also in play. The President was a Georgian, the Vice-President was from Louisiana and the capital was to be in South Carolina. Clearly, in order that the more populous states should not seem to exert an undue share of influence, Mississippi, Alabama and Florida must be honored with appointments to the highest available offices. The new President was a moderate, as were all his close friends and allies. They believed it was essential to their chances of attracting the other Southern states that the new government be seen to be in the hands of moderates and not radicals and ‘fire-eaters’. Unstated was the assumption that a moderate, conservative government that based its case on states’ rights would be more appealing to foreign governments than a ‘fire-eating’, pro-slavery one. In order of importance, the six cabinet offices would be State, Treasury, War, Justice, Navy and the Post. War must go to Jefferson Davis, should he be well enough to accept it; Davis had been an exceptional Secretary in the Pierce administration and would be a popular choice, as well as a fulfillment of the obligation to Mississippi. The Navy could be offered to Stephen Mallory of Florida, who had extensive experience in naval and maritime affairs. The State Department must go to an Alabamian, and as William Yancey was too ‘ultra’ and too ill besides, the lesser-known Jabez Curry would receive the nod. Treasury must go to Memminger or Trenholm of South Carolina as they were the closest to financial experts that the South could offer. That left Judah Benjamin of Louisiana for Attorney General, a post for which the affable and talented man from New Orleans was perhaps not well suited, but a man of his talents must be gotten into the administration somehow. Having disposed of the major offices, Toombs proposed to offer the Postmaster’s hat to fatherly Robert Barnwell of South Carolina. He would have liked to have his good friend Alexander Stephens in the Cabinet as well, but would content himself with having a sure ally in the Congress instead.

And what of Howell Cobb, whose dreams of the Presidency had been shattered, and his brother Thomas, whose ambitions had been transparent enough to be the subject of scorn and derision from the other delegates? Howell was named presiding officer of the Provisional Congress and had done a competent if not inspiring job. His revelation of the contents of Bright’s letter had been calculated to vault him to the front-runner’s position for the Presidency, but other delegates had more accurately assessed the import of the news. Bright had only a short time remaining in office, they noted, and the reaction of the Northern public to Bright’s proposals was unlikely to be kind. Consequently, they reasoned, the best way to make use of Howell Cobb’s influence with Bright – and to remove his interference with their own presidential hopes – was to send him to Washington, post-haste, as a negotiator and advocate for the new Confederacy. Cobb must have known it was a form of political exile, but he was patriot enough to take up the task as directed. Before he could arrive in Washington the storm had well and truly broken; Bright was on trial for treason and was under virtual house arrest, certainly unable to see an ambassador from the rebellious states. Doubly crushed, Cobb returned to Montgomery and took up his former post as presiding officer, well aware that his old enemy Toombs would have no position in the administration for him. His brother Tom had also taken the temper of the proceedings and found the prospects for advancement sour. Declaring that he would not accept a Cabinet position below State, and perhaps not even that, Tom Cobb had put on his white gloves and boarded the train for Georgia.

The Provisional Congress could and did enact a sum of fiat money, essentially promissory notes to state banks, to be redeemed when the country was able to collect taxes and tariffs. An issue of bonds was eagerly subscribed by wealthy planters, and for the moment the new republic was equipped with credit necessary for its needs. The most pressing of those needs was the establishment of a national army to regularize and supplement the militias of the various states. The Yankees were not thought to be a serious threat in the short term – in Lincoln’s inaugural address he had promised to ‘suspend’ federal activities in the rebellious states ‘for a time’ – but everyone thought it was better to be safee than sorry. The arrival of P G T Beauregard in Columbia proved fortuitous as it enabled Toombs to unload most of the organizational work of the new army onto the Creole’s shoulders. The Secretary of War would be fully occupied with the setting up of the administrative and logistical elements of the service, in particular the supply of weapons, gunpowder, uniforms and rations. Most of this would have to come from foreign sources, until or unless the Confederacy could develop its own resources. Beauregard’s advice was frequently also sought on matters such as the construction of coastal fortifications and the design of a new national capitol, intended to grace the high ground to the east of the city.

In the North, Lincoln had likewise settled his Cabinet. Most of the hard choices had been made after his nomination, for the new President was determined to staff his administration with as many capable men of the new Republican Party as possible, and with as many Democrats as could be persuaded to join. To William Seward of New York, the elder statesman of the young Party, must go the most prestigious post: the State Department. Salmon Chase of Ohio would take the Treasury, though Seward did not want him in the Cabinet at all. Montgomery Blair from the critical state of Missouri would receive the War Department; Simon Cameron of Pennsylvania had coveted the Treasury, or the War office as a lesser prize, but the odor of corruption that clung to him made his confirmation impossible. He was instead sent to be Minister to France, disgruntled but unable to find anyone in the Party to take his side. Lincoln’s most surprising choice was to offer to bring in his old opponent Stephen Douglas as Attorney General. Dispirited and in ill-health, Douglas at first refused, but Lincoln tendered the offer a second time and Douglas agreed for the sake of national unity. Democrat Edwin Stanton would continue as Secretary of the Interior, having served in that capacity in the last days of the ‘dead duck’ Bright administration. Gideon Welles of Connecticut was a popular choice to head the Navy, and Edward Bates of the key state of Maryland would be Postmaster.

With the dead hand of the Bright administration removed the Congress, less the members from the seceded states, remained in session and strove diligently to produce a compromise that would bring the errant Southern states back into the Union. Taking their cue from Lincoln, Republicans participated in these discussions while remaining skeptical of any chance of success. “Let us not impede these discussions, if a compromise can be had without our giving up any of the critical points on which the administration was elected,” one Washington newspaper editor urged. “But let us make no shameful peace.” And so began the period of ‘watchful waiting’, or ‘masterly inactivity’, the North refusing to offer provocation and the Upper South refusing to secede without cause. Delegations from the Confederacy visited the Border and Upper South, but to no immediate avail. The men of those states who favored secession were a minority, and lacked the influence to carry their states out of the Union.

That did not mean the Lincoln administration was wholly idle, for supplementary appropriations were immediately necessary for the expansion of the Army and Navy, and for bringing the state militias to a higher standard of readiness. To Democrats who denounced these measures as ‘provocative’ and ‘infamous’, Lincoln merely replied that the Southern states were rapidly recruiting a large army, and that while he proposed no invasion at this time, to see to the national defense was only prudent. Pursuant to this, Lincoln was meeting on April 1st with the principal members of his military team, Secretary Blair, General of the Army Winfield Scott and the Commandant of Cadets at West Point, W T Sherman, when word arrived by telegraph that an armed gang had descended upon the little town of Harpers Ferry in western Virginia. Then the telegraph had gone dead, presumably cut by the invaders.

At that time, Harpers Ferry was a small town of only modest importance. Water power from the Shenandoah and Potomac Rivers had been its original reason for existence, but transportation along the Potomac canal was limited, and steam power had made water power of limited utility. Then the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad had come, riding the same gaps in the mountains that allowed the Potomac River to pass, and Harpers Ferry had gained a new lease on life as a way-station between the Ohio River valley and the great cities of the east. Through it all there had been the federal arsenal, a complex of buildings that used water power to shape gun butts, drill rifle barrels and carry out the hundreds of mechanical operations necessary to make small arms. It was for this stock of over 100,000 rifles and muskets, and for the gunpowder and ammunition stored nearby, that the raiders had come.

John Brown

As the world would soon know, their leader was a man named John Brown. A fervent abolitionist, Brown had taken his own advice to direct action in Kansas, killing at least eight pro-slavery farmers. As Lincoln’s election came and as the six Southern states went out of the Union, Brown had joined his voice to that of prominent New England men to urge immediate, direct action. Disgusted with Lincoln’s cautious, pragmatic policy, Brown had embarked on a speaking tour designed to raise money for a bold stroke, a move he predicted would electrify the nation. His exact intentions were disclosed to only a very few: John Brown would seize the arsenal, arm the slaves and raise the region in revolt.

Any sober contemplation would have revealed dozens of flaws, any one of which would serve to doom the plan outright. But if Brown’s plans were faulty his righteous indignation convinced his supporters to fund, equip and in some cases to join his tiny band. No more than thirty men marched over the railroad bridge in the early morning hours of April 1st, and few of them had any practical knowledge of military matters. Whatever plan Brown might have had went by the wayside when a night watchman put a bullet into Brown’s son, Watson. In the melee that followed, Brown’s supporters torched the better part of the town and retreated into the arsenal works to await the slaves they confidently expected to flock to their standard.

In mid-morning a B&O train was fired upon as it neared the Harpers Ferry station, probably by angry residents who had taken up positions on the heights around the town from which they could pepper the thick masonry walls of the arsenal. The engineer was wounded but managed to open the throttle and speed past, sending out an alert from the next stop. This telegraph was received at the War Department and forwarded to the White House in mid-morning of April 1st where it was read with amazement by President Lincoln and General Winfield Scott. After only a few minutes of deliberation it was settled that Colonels Sherman and Grant would take charge of any troops available in the Washington area and proceed at once to the site.

Last edited:

stnylan - I've played up New England's reaction a bit from our history for story purposes. Yes, I agree that the 'starting position' is much more complex than in our history. We'll just have to hope Lincoln - and the rest of the North - are up for it.

New England had a history of political unorthodoxy; witness the early popularity of abolitionism in that region. So I think it would have been tough to get popular support for secession, but events can stampede intentions.

J. Passepartout - I'm conceited enough to take that as a credit to my writing ( ). Please let me know if I veer off from the believable.

). Please let me know if I veer off from the believable.

Fulcrumvale - War? What war? A rebellion we have, but... no war. If Bright let the seceding states go and Lincoln decides not to press the issue (he hasn't yet but he might) then, where's the war?

I wrote the events for these next six months and decided to just play the game and let things go as they would. It was always possible that there would be no Civil War. I'm not saying yet if that is true or not, just... stay with me until we get there.

Edit: Certainly Brown's raid can't help.

TheExecuter - certainly no offense could be taken; I respect Parliament as the model for our own assembly. I enjoyed writing that scene and I'm glad you enjoyed reading it. I believe the deciding votes against were from men who didn't want the very Southern VP to move up.

Draco Rexus - no, I understand why you are concerned. I share your feelings; that's why I've pumped my mobilization pool up past 30 divisions. We'll just have to see if they are needed, and if so will they be enough?

GhostWriter - thank you! I enjoyed speaking with you this week also.

coz1 - NO ONE EXPECTS THE RAID ON HARPERS FERRY!

Um... yeah, maybe they do. Still, what's 1861 without old Brown hiking into Harpers Ferry to see what sort of trouble he can raise?

Still, what's 1861 without old Brown hiking into Harpers Ferry to see what sort of trouble he can raise?

The update just past is dry but I think necessary. Next time we get Sam and Cump at the Ferry... sure to be fun.

New England had a history of political unorthodoxy; witness the early popularity of abolitionism in that region. So I think it would have been tough to get popular support for secession, but events can stampede intentions.

J. Passepartout - I'm conceited enough to take that as a credit to my writing (

Fulcrumvale - War? What war? A rebellion we have, but... no war. If Bright let the seceding states go and Lincoln decides not to press the issue (he hasn't yet but he might) then, where's the war?

I wrote the events for these next six months and decided to just play the game and let things go as they would. It was always possible that there would be no Civil War. I'm not saying yet if that is true or not, just... stay with me until we get there.

Edit: Certainly Brown's raid can't help.

TheExecuter - certainly no offense could be taken; I respect Parliament as the model for our own assembly. I enjoyed writing that scene and I'm glad you enjoyed reading it. I believe the deciding votes against were from men who didn't want the very Southern VP to move up.

Draco Rexus - no, I understand why you are concerned. I share your feelings; that's why I've pumped my mobilization pool up past 30 divisions. We'll just have to see if they are needed, and if so will they be enough?

GhostWriter - thank you! I enjoyed speaking with you this week also.

coz1 - NO ONE EXPECTS THE RAID ON HARPERS FERRY!

Um... yeah, maybe they do.

The update just past is dry but I think necessary. Next time we get Sam and Cump at the Ferry... sure to be fun.

The first shots?

This little contretemps in Harper's Ferry has decidedly lethal potential.

Interesting round-up of the two cabinets. So Davis is back in his old job, so to speak. Will be interesting to see what verdict is reached of him in this capacity as opposed to his real-life role.

This little contretemps in Harper's Ferry has decidedly lethal potential.

Interesting round-up of the two cabinets. So Davis is back in his old job, so to speak. Will be interesting to see what verdict is reached of him in this capacity as opposed to his real-life role.

Good picture of Brown. The museums in Harpers Ferry have many likenesses of the man, and he does have some fearsome eyes.

Interesting change in officers to lead the punitive expedition.

Vann

Interesting change in officers to lead the punitive expedition.

Vann

Well, the respective Cabinets are set, as are the Congresses. We know how the Southern population feels, but just how does the general public in the North feel about this move of the Deep South? For that matter, how does the populace of the Border States feel? I wonder if the right sort of propaganda campaign might bring the Border States into the Northern fold?

Although Mr. Brown's impulsive activities might just blow everything up.

Ah, my friend, what a tense cliff you've left us hanging on. Thanks!

Although Mr. Brown's impulsive activities might just blow everything up.

Ah, my friend, what a tense cliff you've left us hanging on. Thanks!

Considering the rather minor, in my mind, details that historically caused the Upper South to secede, I have no hopes for a Harper's Ferry so placed in time.

Indeed, Brown's raid does little to assist the deliberations of Virginia at least if no the other border states. And so it is to be Grant and Sherman that answer the call. Certainly not Lee in this TL.

While you may think it dry, Director, it is necessary to set up the chessboard, so to speak. And you did that masterfully without boring your audience but explaining precisely why each individual ended up where they have as well as adding this juicy little detail to the end. Nice.

While you may think it dry, Director, it is necessary to set up the chessboard, so to speak. And you did that masterfully without boring your audience but explaining precisely why each individual ended up where they have as well as adding this juicy little detail to the end. Nice.

Director: ...Toombs telegraphed .. he must have funds, and secondly he must have expert engineering assistance.

that is good. back to basics. a good plan starts with a good foundation ! !

Director: ...Cobb must have known it was a form of political exile, but he was patriot enough to take up the task as directed.

that is good. the South has no chance with petty bickering going on ! !

Director: ...The arrival of P G T Beauregard in Columbia proved fortuitous as it enabled Toombs to unload most of the organizational work of the new army onto the Creole’s shoulders.

wonderful ! !

Director: ...Beauregard’s advice was frequently also sought on matters such as the construction of coastal fortifications and the design of a new national capitol, intended to grace the high ground to the east of the city.

IRL did not that high ground eventually became Fort Jackson ? (where i took basic training in October/November 1963.)

Director: ...Lincoln’s most surprising choice was to bring .. Stephen Douglas as Attorney General.

that has to be a fantastic move ! !

Director: ...“But let us make no shameful peace.”

excellent ! !

Director: ...supplementary appropriations were immediately necessary for the expansion of the Army and Navy, and for bringing the state militias to a higher standard of readiness.

and, very appropriate for the times ! !

Director: ...Harpers Ferry .. After only a few minutes of deliberation it was settled that Colonels Sherman and Grant would take charge of any troops available in the Washington area and proceed at once to the site.

that should make short work of John Brown and company ! !

dry ? ? no way ! ! awesome update ! ! very informative ! !

that is good. back to basics. a good plan starts with a good foundation ! !

Director: ...Cobb must have known it was a form of political exile, but he was patriot enough to take up the task as directed.

that is good. the South has no chance with petty bickering going on ! !

Director: ...The arrival of P G T Beauregard in Columbia proved fortuitous as it enabled Toombs to unload most of the organizational work of the new army onto the Creole’s shoulders.

wonderful ! !

Director: ...Beauregard’s advice was frequently also sought on matters such as the construction of coastal fortifications and the design of a new national capitol, intended to grace the high ground to the east of the city.

IRL did not that high ground eventually became Fort Jackson ? (where i took basic training in October/November 1963.)

Director: ...Lincoln’s most surprising choice was to bring .. Stephen Douglas as Attorney General.

that has to be a fantastic move ! !

Director: ...“But let us make no shameful peace.”

excellent ! !

Director: ...supplementary appropriations were immediately necessary for the expansion of the Army and Navy, and for bringing the state militias to a higher standard of readiness.

and, very appropriate for the times ! !

Director: ...Harpers Ferry .. After only a few minutes of deliberation it was settled that Colonels Sherman and Grant would take charge of any troops available in the Washington area and proceed at once to the site.

that should make short work of John Brown and company ! !

dry ? ? no way ! ! awesome update ! ! very informative ! !

Ah, so much has happened and the country (or are they countries already?) is teetering on the brink. Earlier, after I read the updates about the formation of the Confederacy, Bright's impeachment trial and Lincoln's inauguration, but before I read the last update, I was thinking that this Lincoln probably will not fall to an assassin's bullet: he's cautious and careful not to offend the Southern border states, but in being so, he's being overtaken left and right (or South, West and Northeast, if you will) by those who are willing to bear enormous risks for their own purposes and are willing to break up the country. While not offending the Border States might work (and be the right approach) for those states, the Confederacy and other assorted extremists/secessionists don't play by those rules. So Lincoln might end up saving the Border States for the Union, but losing far more states everywhere else: California, Utah, the Northeast... And what about the Northwest, where Britain held claims not very long ago? Might not weakness in other parts of the US lead to renewed British interest in those parts?

But those were my pessimistic thoughts before the last update and Harpers Ferry. Now that that incident has come to pass, I must seriously doubt whether Lincoln can even keep the Border States in the fold. If I read the situation right, the Border States are basically neutral up until Harpers Ferry: not too thrilled with Lincoln and his Republican administration, but not fired up enough to join the Confederacy. Along come John Brown, embodying the worst of Northern Abolitionism. That's going to rub a lot of Border Staters wrong. And then Lincoln sends in the Federal Army, commanded by two Northern (Midwestern?) officers... I fear that's going to give the secessionist hotheads in the Border States a field day: not one, but two examples of Northern 'aggression'.

Lincoln needs to get his act together, or events need to validate his current course of inaction. Quickly. Otherwise, the country will splinter and Lincoln will be hounded out of office in four years (maybe earlier, if the Senate has gotten a taste for impeachment proceedings).

Of course, it could be that Harpers Ferry will be a shining hour for Lincoln, the "end of the beginning", to paraphrase Churchill, after which he leads the Union to diplomatic (and, sooner or later, military) victory, but right now things look pretty bleak to me.

Excellent writing, as always, Director. I look forward to further developments.

But those were my pessimistic thoughts before the last update and Harpers Ferry. Now that that incident has come to pass, I must seriously doubt whether Lincoln can even keep the Border States in the fold. If I read the situation right, the Border States are basically neutral up until Harpers Ferry: not too thrilled with Lincoln and his Republican administration, but not fired up enough to join the Confederacy. Along come John Brown, embodying the worst of Northern Abolitionism. That's going to rub a lot of Border Staters wrong. And then Lincoln sends in the Federal Army, commanded by two Northern (Midwestern?) officers... I fear that's going to give the secessionist hotheads in the Border States a field day: not one, but two examples of Northern 'aggression'.

Lincoln needs to get his act together, or events need to validate his current course of inaction. Quickly. Otherwise, the country will splinter and Lincoln will be hounded out of office in four years (maybe earlier, if the Senate has gotten a taste for impeachment proceedings).

Of course, it could be that Harpers Ferry will be a shining hour for Lincoln, the "end of the beginning", to paraphrase Churchill, after which he leads the Union to diplomatic (and, sooner or later, military) victory, but right now things look pretty bleak to me.

Excellent writing, as always, Director. I look forward to further developments.

stnylan - Hey, the game event for John Brown's raid came up... and I have to admit the timing is not good.

Davis was a pretty fair administrator but as he got older could not deal with opposing points of view. His neuralgia of the eye (probably from a venereal disease contracted in Mexico) was incredibly painful and borderline lethal.

Toombs probably did lose the Confederate Presidency because he was falling-down-drunk at a party a few days before the vote. He's a brilliant but mercurial man... we'll see how he works out.

Vann the Red - I'm always skeptical - and a little frightened - of men who are absolutely certain. Their ends usually involve painful means.

As for the inclusion of Grant and Sherman, well... there is a reason. And they are fun to write about. Historically Lee was followed at West Point by Hardee (1855-1860), Beauregard (a few months) and then John Reynolds. Sherman is a little young for the position... but perhaps someone influential whispered in Scott's ear, eh?

Historically Lee was followed at West Point by Hardee (1855-1860), Beauregard (a few months) and then John Reynolds. Sherman is a little young for the position... but perhaps someone influential whispered in Scott's ear, eh?

Draco Rexus - rather like a patient who has been deeply traumatized I doubt the Northern population knows quite what they feel right now. But soon there will grow a slow but terrible anger.

Here comes a little shove off that cliff...

J. Passepartout - Every stone in an avalanche has weight. I admit my choice here is to write about the raid, not to give it great importance. The real effects won't be felt in the South so much as elsewhere.

coz1 - Lee will have his day, I promise you. And the following post(s) should inject a bit of action into the narrative.

GhostWriter - I actually 'inferred' that there had to high ground outside Columbia somewhere but haven't a good enough map to know exactly where. It does make sense to me that a nearby rise would be co-opted for a new national capitol... fascinating that there is an army base there; I didn't know. Sometimes you guess and get lucky.

but haven't a good enough map to know exactly where. It does make sense to me that a nearby rise would be co-opted for a new national capitol... fascinating that there is an army base there; I didn't know. Sometimes you guess and get lucky.

Stuyvesant - the policy of the Lincoln administration I lay out is what was actually done in our history, with the exception that there has - so far - been no event like Fort Sumter to trigger hostilities. With the 'negotiable' patriotism of the Upper South and Border I think Lincoln is wise to feel out what the public will support, and also wise to give the Confederacy some rope with which to hang itself. Remember that the South is not peopled with patient, thoughtful men.

I agree that Lincoln needs to act, hence the increased funding for army and navy. But he doesn't have the luxury of guessing wrong...

Further developments follow.

Davis was a pretty fair administrator but as he got older could not deal with opposing points of view. His neuralgia of the eye (probably from a venereal disease contracted in Mexico) was incredibly painful and borderline lethal.

Toombs probably did lose the Confederate Presidency because he was falling-down-drunk at a party a few days before the vote. He's a brilliant but mercurial man... we'll see how he works out.

Vann the Red - I'm always skeptical - and a little frightened - of men who are absolutely certain. Their ends usually involve painful means.

As for the inclusion of Grant and Sherman, well... there is a reason. And they are fun to write about.

Draco Rexus - rather like a patient who has been deeply traumatized I doubt the Northern population knows quite what they feel right now. But soon there will grow a slow but terrible anger.

Here comes a little shove off that cliff...

J. Passepartout - Every stone in an avalanche has weight. I admit my choice here is to write about the raid, not to give it great importance. The real effects won't be felt in the South so much as elsewhere.

coz1 - Lee will have his day, I promise you. And the following post(s) should inject a bit of action into the narrative.

GhostWriter - I actually 'inferred' that there had to high ground outside Columbia somewhere

Stuyvesant - the policy of the Lincoln administration I lay out is what was actually done in our history, with the exception that there has - so far - been no event like Fort Sumter to trigger hostilities. With the 'negotiable' patriotism of the Upper South and Border I think Lincoln is wise to feel out what the public will support, and also wise to give the Confederacy some rope with which to hang itself. Remember that the South is not peopled with patient, thoughtful men.

I agree that Lincoln needs to act, hence the increased funding for army and navy. But he doesn't have the luxury of guessing wrong...

Further developments follow.

The Bright administration being dogmatically Democratic, it had found little money or enthusiasm for the Military Academy located on the grounds of the old Hudson fortifications at West Point. The development of a class of professional officers was said to be elitist, and was denounced as not at all in keeping with the popular roots of the people’s party. But there was no denying that the last commandant, Robert E Lee of Virginia, had instituted the highest standards of deportment and academic achievement for the cadets. Too, there was the enviable record of engineering achievements of the men who had graduated from the academy, and no small amount of popular good-will accrued by the Army’s successes in Mexico, Madagascar and Borneo. Unwilling to add to its many other troubles the Bright administration had largely decided to ignore the academy wherever possible.

Despite his successes in revamping the curriculum and re-establishing discipline, Lee had grown tired of the constant battles for funding and the unending stream of skeptical Congressional inspectors. The death of his wife had made settling the complex affairs of her estate an urgent necessity, and so Lee had left the Hudson highlands and returned to Virginia. The empty position of commandant had proven difficult to fill, for the senior officers of the army had all been aware of Lee’s battles with the administration over funding and autonomy. At last it had fallen to General of the Army Winfield Scott to propose a suitable compromise. A rising young Congressman from Ohio had made a national name for himself as part of an investigation into the violence in Kansas. That Congressman had a brother who had attended West Point, served in California during the Mexican War and then retired from the service to take charge of a military academy in Louisiana. With his military and educational experience this man would be an ideal candidate; the influential members of the Democratic Congressional delegation from Louisiana were mightily impressed with his talents, and the Republicans would embrace him for hi brother’s sake.

Thus it was with the benefit of a recall to active duty and a brevet promotion to Colonel that William T Sherman came to the Commandant’s office at West Point. If he found the work challenging, opinion was unanimous that he was effective, efficient and popular, especially with the younger cadets. Observed Colonel Don Carlos Buell, “If you had hunted the whole army, from one end of it to the other, you could not have found a man in it more admirably suited for the position in every respect than Sherman.” Noted graduating cadet Emory Upton of New York, “He was everywhere and knew everything. He accepted nothing from us but the most complete effort… One encounter with Sherman would terrify even the most hardened dodger.” It was therefore no surprise, with secession underway and war clouds threatening on every horizon, that Sherman should be one of the officers called to Washington to brief the new President on the state of the Army. It was in the middle of one of those extended meetings that Sherman, Scott, Lincoln and Grant first heard the news of John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry. Almost instantly, Sherman volunteered to go take charge of the situation, and as General Scott was obviously too aged and infirm to make the trip the President tactfully suggested that Colonel Grant should accompany Colonel Sherman instead.

Grant looked out of the window at the scenery speeding past, quiet farms and rolling hills covered in trees just bursting forth in new green leaves. On the other side of the coach could be seen the rocky, tumbling waters of the Potomac and the water meadows along the far shore. Sherman fidgeted, emptying out his pockets and replacing the contents before settling down to clean his revolver. Despite the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad’s famed attention to its track bed, the train was flying along at almost double its usual pace, and the rocking and jolting made it almost impossible for Sherman to keep the parts on his seat. At last he finished the task and returned the cleaning kit to the knapsack under the bench seat he shared with Grant.

The train was rocketing along with no care for other traffic for the events in Harpers Ferry had closed the line to regular service. With visions of lost fares and freight charges dancing before their eyes the managers of the B&O had been eager to set up a special train consisting of a locomotive used for fast passenger service, a tender, one passenger car and three enclosed freight cars, and to place it at the service of the nation. A company of US Marines from the Washington Naval Yard now occupied every square foot of floor space in the cars while their officers and NCOs sprawled on and over the seats. In the uncertain light of a long spring evening the men were playing cards, munching hardtack or checking weapons in preparation for what might come.

“You have a plan in mind?” Sherman asked abruptly. Grant leaned back from the window, startled, for Sherman’s face had seemed to appear suddenly from nowhere, reflected in the glass like an unquiet spirit.

Grant turned and studied his companion, then nodded. Sherman had graduated from West Point three years before Grant, and should therefore be the senior officer. However, Grant had stayed in the Army and gotten his brevet promotion to Colonel while Sherman was still a civilian. Too, Grant was the deputy of the Commanding General, but then again the President and General Scott had clearly intended for Sherman to lead… Grant shrugged, his shoulders barely moving. They would have to sort out who would command but Grant was not disposed to begin an argument. “Go right at them,” he said, and shrugged again. “Do you have a plan, sir?”

Sherman squinted at him, then relaxed. “Have you sorted out who is in charge here?”

“Reckon it’s you; least the President and General Scott think so.”

“Huh. How about we see if we can figure a way through this mess first and worry about who’s in charge later? I think our superiors just want the bandits taken care of, and I agree with that. My friends call me Cump, for Tecumseh.”

“Suits me. My friends call me Sam.” Grant’s tiny smile held a grain of bitterness; Sherman suspected he didn’t have many friends. They hadn’t known each other at West Point, not with three years between them, and Sherman hadn’t heard much about Grant in the years since. He’d gotten into combat in the Mexican War, which was more than Sherman could claim, but since then he’d been invisible.

“Just go right at them? That’s your plan?” Sherman’s voice rose, the pitch rising on the end of the question. Grant flashed him a look and tossed his head at the sleeping men around them, then nodded without meeting his eyes.

“It’s a box. No way in or out ‘cept the railroad. We could get off the train a few miles out and hike it, but that’d mean climbing on trails over those mountains. In the dark. Could take a day, maybe two. I figger we’d best go in fast, go in quiet if we can. That means riding the train into the station or just past it. You ever been there?”

“Passed through; don’t remember much about it. Big armory buildings… brick, stone, something like that. So you really mean to just go right at them? That’s likely to get us shot up, Sam.”

“Only one railroad in. No way across the river ‘cept the bridge. Can’t hike in by road in less than a day,” Grant repeated, raising his head defiantly. “What, you think I like just bulling at them? But this place… we could get hurt worse tryin’ to be clever, I think. Tracks follow the canal, cross the river on a bridge, turn hard right once they hit land, run past the armory to the station. Ain’t no easy way in.”

“Great Jehosaphat, Grant, that’s a death trap! If we ride in on the train we’ll have to slow at the curve and then they’ll shoot us full of holes!”

Grant shrugged again. “Maybe. Probably not. No loopholes in the armory walls. No easy way to knock through a couple of feet of brick. ‘Sides, Cump, these aren’t soldiers, are they? They’re bandits. They might block the tracks, but if they want to shoot at a train they’ll have to come outside to do it.”

“Any artillery at this armory?”

“Might be a few old pieces but I doubt it. The Ferry makes rifles; that’s all it’s ever done.”

Sherman slumped back in his seat, then sat bolt upright again. “You know, Sam, to be so quiet you are one genuinely crazy man. But I guess we have a plan, assuming the bandits aren’t any crazier than you are. This seat is a torture. We’re making good time, though. Wonder how fast… How long until we get there?”

“I asked the railroad to send a man with us; he’s a conductor on the route and knows the landmarks. I asked him to stop the train a mile or two before the bridge. We can walk up and see if… if we’re expected.”

Sherman gave him another hard stare, then relented. “That was good thinking, Sam. We can scout out the land; maybe cross the bridge on foot. There’ll be some militia we can talk to, find out what’s going on.”

“Militia?”

“This is Virginia; therefore militia will be present. It’s the way the South works.” Sherman grinned and jerked out of his seat. “You catch a nap if you can. I’m going to go find that railroad man.”

Despite his successes in revamping the curriculum and re-establishing discipline, Lee had grown tired of the constant battles for funding and the unending stream of skeptical Congressional inspectors. The death of his wife had made settling the complex affairs of her estate an urgent necessity, and so Lee had left the Hudson highlands and returned to Virginia. The empty position of commandant had proven difficult to fill, for the senior officers of the army had all been aware of Lee’s battles with the administration over funding and autonomy. At last it had fallen to General of the Army Winfield Scott to propose a suitable compromise. A rising young Congressman from Ohio had made a national name for himself as part of an investigation into the violence in Kansas. That Congressman had a brother who had attended West Point, served in California during the Mexican War and then retired from the service to take charge of a military academy in Louisiana. With his military and educational experience this man would be an ideal candidate; the influential members of the Democratic Congressional delegation from Louisiana were mightily impressed with his talents, and the Republicans would embrace him for hi brother’s sake.

Thus it was with the benefit of a recall to active duty and a brevet promotion to Colonel that William T Sherman came to the Commandant’s office at West Point. If he found the work challenging, opinion was unanimous that he was effective, efficient and popular, especially with the younger cadets. Observed Colonel Don Carlos Buell, “If you had hunted the whole army, from one end of it to the other, you could not have found a man in it more admirably suited for the position in every respect than Sherman.” Noted graduating cadet Emory Upton of New York, “He was everywhere and knew everything. He accepted nothing from us but the most complete effort… One encounter with Sherman would terrify even the most hardened dodger.” It was therefore no surprise, with secession underway and war clouds threatening on every horizon, that Sherman should be one of the officers called to Washington to brief the new President on the state of the Army. It was in the middle of one of those extended meetings that Sherman, Scott, Lincoln and Grant first heard the news of John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry. Almost instantly, Sherman volunteered to go take charge of the situation, and as General Scott was obviously too aged and infirm to make the trip the President tactfully suggested that Colonel Grant should accompany Colonel Sherman instead.

Grant looked out of the window at the scenery speeding past, quiet farms and rolling hills covered in trees just bursting forth in new green leaves. On the other side of the coach could be seen the rocky, tumbling waters of the Potomac and the water meadows along the far shore. Sherman fidgeted, emptying out his pockets and replacing the contents before settling down to clean his revolver. Despite the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad’s famed attention to its track bed, the train was flying along at almost double its usual pace, and the rocking and jolting made it almost impossible for Sherman to keep the parts on his seat. At last he finished the task and returned the cleaning kit to the knapsack under the bench seat he shared with Grant.

The train was rocketing along with no care for other traffic for the events in Harpers Ferry had closed the line to regular service. With visions of lost fares and freight charges dancing before their eyes the managers of the B&O had been eager to set up a special train consisting of a locomotive used for fast passenger service, a tender, one passenger car and three enclosed freight cars, and to place it at the service of the nation. A company of US Marines from the Washington Naval Yard now occupied every square foot of floor space in the cars while their officers and NCOs sprawled on and over the seats. In the uncertain light of a long spring evening the men were playing cards, munching hardtack or checking weapons in preparation for what might come.

“You have a plan in mind?” Sherman asked abruptly. Grant leaned back from the window, startled, for Sherman’s face had seemed to appear suddenly from nowhere, reflected in the glass like an unquiet spirit.

Grant turned and studied his companion, then nodded. Sherman had graduated from West Point three years before Grant, and should therefore be the senior officer. However, Grant had stayed in the Army and gotten his brevet promotion to Colonel while Sherman was still a civilian. Too, Grant was the deputy of the Commanding General, but then again the President and General Scott had clearly intended for Sherman to lead… Grant shrugged, his shoulders barely moving. They would have to sort out who would command but Grant was not disposed to begin an argument. “Go right at them,” he said, and shrugged again. “Do you have a plan, sir?”

Sherman squinted at him, then relaxed. “Have you sorted out who is in charge here?”

“Reckon it’s you; least the President and General Scott think so.”

“Huh. How about we see if we can figure a way through this mess first and worry about who’s in charge later? I think our superiors just want the bandits taken care of, and I agree with that. My friends call me Cump, for Tecumseh.”

“Suits me. My friends call me Sam.” Grant’s tiny smile held a grain of bitterness; Sherman suspected he didn’t have many friends. They hadn’t known each other at West Point, not with three years between them, and Sherman hadn’t heard much about Grant in the years since. He’d gotten into combat in the Mexican War, which was more than Sherman could claim, but since then he’d been invisible.

“Just go right at them? That’s your plan?” Sherman’s voice rose, the pitch rising on the end of the question. Grant flashed him a look and tossed his head at the sleeping men around them, then nodded without meeting his eyes.

“It’s a box. No way in or out ‘cept the railroad. We could get off the train a few miles out and hike it, but that’d mean climbing on trails over those mountains. In the dark. Could take a day, maybe two. I figger we’d best go in fast, go in quiet if we can. That means riding the train into the station or just past it. You ever been there?”

“Passed through; don’t remember much about it. Big armory buildings… brick, stone, something like that. So you really mean to just go right at them? That’s likely to get us shot up, Sam.”

“Only one railroad in. No way across the river ‘cept the bridge. Can’t hike in by road in less than a day,” Grant repeated, raising his head defiantly. “What, you think I like just bulling at them? But this place… we could get hurt worse tryin’ to be clever, I think. Tracks follow the canal, cross the river on a bridge, turn hard right once they hit land, run past the armory to the station. Ain’t no easy way in.”

“Great Jehosaphat, Grant, that’s a death trap! If we ride in on the train we’ll have to slow at the curve and then they’ll shoot us full of holes!”

Grant shrugged again. “Maybe. Probably not. No loopholes in the armory walls. No easy way to knock through a couple of feet of brick. ‘Sides, Cump, these aren’t soldiers, are they? They’re bandits. They might block the tracks, but if they want to shoot at a train they’ll have to come outside to do it.”

“Any artillery at this armory?”

“Might be a few old pieces but I doubt it. The Ferry makes rifles; that’s all it’s ever done.”

Sherman slumped back in his seat, then sat bolt upright again. “You know, Sam, to be so quiet you are one genuinely crazy man. But I guess we have a plan, assuming the bandits aren’t any crazier than you are. This seat is a torture. We’re making good time, though. Wonder how fast… How long until we get there?”

“I asked the railroad to send a man with us; he’s a conductor on the route and knows the landmarks. I asked him to stop the train a mile or two before the bridge. We can walk up and see if… if we’re expected.”

Sherman gave him another hard stare, then relented. “That was good thinking, Sam. We can scout out the land; maybe cross the bridge on foot. There’ll be some militia we can talk to, find out what’s going on.”

“Militia?”

“This is Virginia; therefore militia will be present. It’s the way the South works.” Sherman grinned and jerked out of his seat. “You catch a nap if you can. I’m going to go find that railroad man.”

In Harpers Ferry the passing of the sun behind the western mountains had brought a semblance of peace and quiet. The air was still smoky from the fires that had devastated the merchants at the foot of the hill and then spread upward, fanned by a strong wind blowing upriver. Before they caught fire the homes on the upslope had provided cover for rifle-toting citizens to snipe at the arsenal, but all thought of armed resistance had been lost as the fires spread from one rooftop to another. Men had abandoned their rifles to dash into their burning homes for prized possessions, and then had led their wives and children to safety on the mountain slopes beyond the town. Now flakes of ash drifted past the waning crescent of the moon while pinpoints of flickering light dotted the black hillside, tiny illuminated headstones for the graves of hopes and dreams.

At the foot of the hill by the riverside, the soot-streaked armory buildings sheltered John Brown and his men. A few kept watch while the rest ate, or dozed, or tended to the wounded. A small group of those closest to Brown had gathered at one end of the central structure, circled around their leader and a lantern as men have always sheltered around a fire. These men had pulled packing cases of muskets from head-high stacks of crates and begun their council of war seated upon the implements of modern warfare, all in innocence of the symbolism. As the original purpose of the raid had been to seize the weapons and then retreat to the safety of the mountains, with one voice these acolytes of slave rebellion urged a rapid and immediate withdrawal under cover of night. In the absence of any wagons and horses, and with an armed and angry citizenry across the roads to the west, they must abandon the weapons they had come to find. But a blow had been struck against the slave power, and now they must look to their escape so that they might live to fight another day.

But Brown would not hear of such a plan. “I have come,” he said. “The slaves know this, and they are coming to join me. We shall arm them, and from our stronghold here we will set up a country of free men, a magnet that will pull to it the slaves from across four states. We will drain away the power that supports the South. Against free men in arms, the slave kingdoms must fall.” The fact that twelve hours had passed without a single convert arriving to swell their ranks meant nothing to him. The presence of armed enemies across every road and path by which such reinforcements might arrive, even if anyone outside the little town had heard or approved of the raid, was not something he considered relevant. John Brown had come to Harpers Ferry and placed his destiny in the hands of the Almighty, and was content to abide thereby. Less certain but having no better option, his men bedded down for the night and awaited the dawn.

They were awakened in the moonless dark of the early morning hours by sentries who had heard the unmistakable sound of a locomotive. How far away it was no-one could say, for the constant roar of the rivers in their rocky beds and the peculiar echoes of the river valleys disguised, enhanced and confused the sounds that reached the ear. There had been no way to block the track, not with dozens of armed men camped on the hillside above the arsenal. In addition, fortifying the arsenal had never been a part of a plan that was supposed to rely on shock, surprise and speed. Now they must prepare as best they might, for not a single man doubted the train must be carrying soldiers. They loaded their weapons and they waited, but for the longest while, there was no movement and no sound beyond the roiling of the rivers. Had the train halted, or reversed its course? Were soldiers even now pouring across the railroad bridge? Eyes strained into the darkness but could see nothing.

Then there was the faintest thrum, a rumble as a fall of rocks might make, or the sound of the plucking of a gigantic bass string. One keen-eyed fellow spotted a lightless shape, black silhouetted against the deeper black of the river canyon as a locomotive dashed across the bridge, sparks flickering redly in the air above. They ran outside, ranging themselves behind makeshift barricades between the buildings, cursing at the occasional puff of dust that meant someone on the hillside had seen them, or was perhaps merely firing blind.

The train had slowed somewhat for the sharp curve at the foot of the bridge and the more adventurous of Brown’s men poked their heads around the corners of the armory buildings and let fly. Bullets whanged off the locomotive, some smashing the glass in the unlit lantern and others ringing off the bell to peal a somber warning. The glass windows of the cab were blown in, the wounded engineer falling with the whistle cord in one hand and the throttle in the other. Venting steam and boiling water from a dozen holes, whistle screaming in anguish, the train swept past, wounded but charging too hard to be stopped by mere bullets. Then the soldiers were firing volleys as the cars swept past, Brown’s men bowled over like tenpins, wounded men on both sides screaming and over it all the crash of breaking glass, the crack of splintering wood, the whack of bullets smashing into masonry…

… and then the train was past, Brown’s men scrambling for the safety of the armory rather than risk a dash onto the tracks to fire into the retreating cars.

It was three o’clock in the morning of April 2nd, 1861. On his bed of muskets, covered by a tattered old blanket, John Brown slept fitfully.

No-one else slept at all.

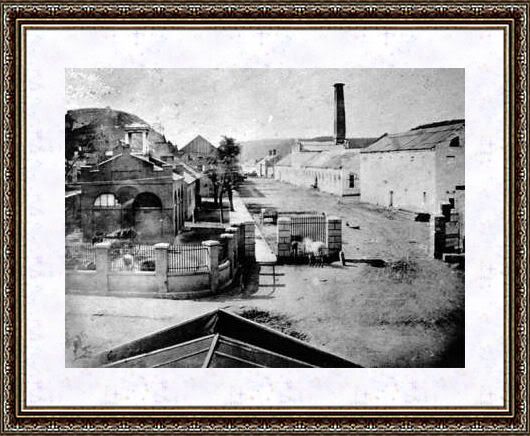

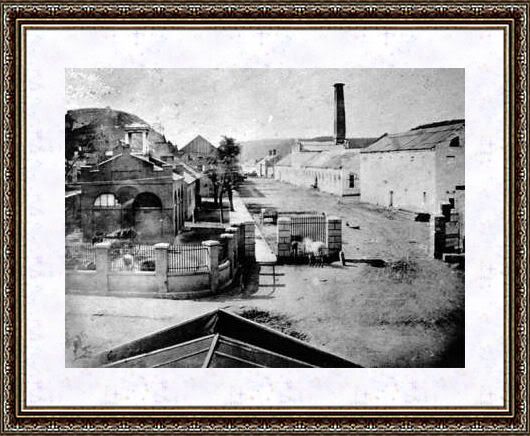

Looking north from the foot of the peninsula. The bridge is behind and to the right, the armory buildings are the large white buildings on the right. The railroad tracks are to the right of the armory and the Potomac River lies beyond that.

At the foot of the hill by the riverside, the soot-streaked armory buildings sheltered John Brown and his men. A few kept watch while the rest ate, or dozed, or tended to the wounded. A small group of those closest to Brown had gathered at one end of the central structure, circled around their leader and a lantern as men have always sheltered around a fire. These men had pulled packing cases of muskets from head-high stacks of crates and begun their council of war seated upon the implements of modern warfare, all in innocence of the symbolism. As the original purpose of the raid had been to seize the weapons and then retreat to the safety of the mountains, with one voice these acolytes of slave rebellion urged a rapid and immediate withdrawal under cover of night. In the absence of any wagons and horses, and with an armed and angry citizenry across the roads to the west, they must abandon the weapons they had come to find. But a blow had been struck against the slave power, and now they must look to their escape so that they might live to fight another day.

But Brown would not hear of such a plan. “I have come,” he said. “The slaves know this, and they are coming to join me. We shall arm them, and from our stronghold here we will set up a country of free men, a magnet that will pull to it the slaves from across four states. We will drain away the power that supports the South. Against free men in arms, the slave kingdoms must fall.” The fact that twelve hours had passed without a single convert arriving to swell their ranks meant nothing to him. The presence of armed enemies across every road and path by which such reinforcements might arrive, even if anyone outside the little town had heard or approved of the raid, was not something he considered relevant. John Brown had come to Harpers Ferry and placed his destiny in the hands of the Almighty, and was content to abide thereby. Less certain but having no better option, his men bedded down for the night and awaited the dawn.

They were awakened in the moonless dark of the early morning hours by sentries who had heard the unmistakable sound of a locomotive. How far away it was no-one could say, for the constant roar of the rivers in their rocky beds and the peculiar echoes of the river valleys disguised, enhanced and confused the sounds that reached the ear. There had been no way to block the track, not with dozens of armed men camped on the hillside above the arsenal. In addition, fortifying the arsenal had never been a part of a plan that was supposed to rely on shock, surprise and speed. Now they must prepare as best they might, for not a single man doubted the train must be carrying soldiers. They loaded their weapons and they waited, but for the longest while, there was no movement and no sound beyond the roiling of the rivers. Had the train halted, or reversed its course? Were soldiers even now pouring across the railroad bridge? Eyes strained into the darkness but could see nothing.

Then there was the faintest thrum, a rumble as a fall of rocks might make, or the sound of the plucking of a gigantic bass string. One keen-eyed fellow spotted a lightless shape, black silhouetted against the deeper black of the river canyon as a locomotive dashed across the bridge, sparks flickering redly in the air above. They ran outside, ranging themselves behind makeshift barricades between the buildings, cursing at the occasional puff of dust that meant someone on the hillside had seen them, or was perhaps merely firing blind.

The train had slowed somewhat for the sharp curve at the foot of the bridge and the more adventurous of Brown’s men poked their heads around the corners of the armory buildings and let fly. Bullets whanged off the locomotive, some smashing the glass in the unlit lantern and others ringing off the bell to peal a somber warning. The glass windows of the cab were blown in, the wounded engineer falling with the whistle cord in one hand and the throttle in the other. Venting steam and boiling water from a dozen holes, whistle screaming in anguish, the train swept past, wounded but charging too hard to be stopped by mere bullets. Then the soldiers were firing volleys as the cars swept past, Brown’s men bowled over like tenpins, wounded men on both sides screaming and over it all the crash of breaking glass, the crack of splintering wood, the whack of bullets smashing into masonry…

… and then the train was past, Brown’s men scrambling for the safety of the armory rather than risk a dash onto the tracks to fire into the retreating cars.

It was three o’clock in the morning of April 2nd, 1861. On his bed of muskets, covered by a tattered old blanket, John Brown slept fitfully.

No-one else slept at all.

Looking north from the foot of the peninsula. The bridge is behind and to the right, the armory buildings are the large white buildings on the right. The railroad tracks are to the right of the armory and the Potomac River lies beyond that.

Last edited: