Please excuse me if my replies are too short, I'm away from my computer for a few days and I'm too old to be comfortable typing on a cell phone.

It seems to me that this post and your last one paint a different picture of the eastern steppe. Is it surrounded by natural obstacles or are they also in the interior? If they aren't, then I don't see how they would impede conquest from west to east more than the reverse? If they are, then wouldn't they also make it easier for forest zone semi-nomads to transition?

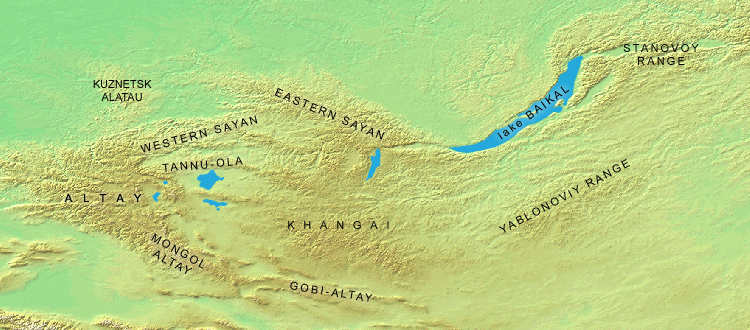

There's mountains inside Mongolia yes. Not as high as the Altai themselves but still significant. Here's a map of the country:

Not obviously they are flat valley in between where nomads dwells but the geography is quite different from the vast western plains.

The Tarim basin is even worse with steeper mountain range and an even more arid climate.

The eastern edge, by the way, is a forest zone, the steppe doesn't reach all the way to the Pacific.

There's another mountain range that separate the Manchurian forest from the Mongolian steppe but otherwise, yes you are correct.

The east to west movement starts with Xiongnu, whose rise is almost exactly parallel to the establishment of the Han empire.

Arguable. The Tocharians started migrating westward before the Xiongnu. Some say because of the pressure of the Xiongnu but they moved to the tarim basin and to Transioxana before the rise of the Xiongnu.

Tributes are a derivative of plunder in the sense that one gets the former by credibly threatening the latter.

Let's just agree to disagree. I don't feel like arguing tonight.

If the western steppe is richer, then how do you explain the frequent victory of the weaker side? The pattern we're talking about is, after all, not the repeated success of western steppe peoples at fending off their neighbors. The Scandinavia example us nice but you don't give us an equivalent to the naval techniques that provided the vikings with their crucial mobility advantage. Horsemanship works for confrontations between steppe peoples and their settled neighbors but not for intra-steppe conflicts. So what is the x factor?

Actually the effectiveness of the Huns/Turks/Mongols are often attributed to innovation in their way of conducting war. But as this is a field I am not confident in, I won't argue it further.

The thing I am more interested is the argument that victories where frequent. In which I have to disagree. I am sure that if you start counting the number of invasions from the east you will be barely find a few. For literally millenias (plural) of history.

Contrast this with the number of "barbarian" invasions we know of in a few centuries of Roman history (most also coming from the east funnily enough)? Or in the dark ages?

No, what actually stand out is how rare those actually rare. The Turkish/Mongols invasion may have been dramatically effective but how many failed coup have never been chronicled? History is written by the winners afterall and while Romans were quick to boast about the dozens of people they crushed, we do not know how many tribes migrated westward and were just absorbed or crushed by those already present.

The case of the Avars and the Huns is particularly interesting in how different they were. The Avars resettlement and conquest was dramatically fast. The Xiongnu/Huns? Not so much. It took centuries from the collapse of their empire to them appearing in the doorstep of Rome. What happened in between? Difficult to ascertain.

And in the case of the Avar, they really did not subjugate any of the western nomadic realms. The Turks did yes but not the Avars. They subjugated a lot of settled europeans tribes and weaker nomadic tribe but I don't remember any major conflict recorded before they started fighting the Roman Empire. To be fair the steppes was still in flux after the collapse of the Huns but yes. Interesting fact nonetheless.