A Time for Changin’ – June 1950 – January 1951

While the campaign in Benin-Nigeria at the beginning of the year had been costly for the United States and her allies, General Patton believed that the longer an attack on the second syndicalist West African enclave – based around the syndicalist Republics of Senegal, Guinea and Sierra Leone – the stronger their defences would become as a the large numbers of soldiers evacuated out of Lagos reorganised and the Internationale readied its defences. The quick opening of a second front would be key.

The first step towards this aim wasn’t to be wielded by the United States, at least not primarily, but by their Brazilian comrades in arms in the islands of Cape Verde. The islands had been at the centre of fierce naval competition for many years, and were home to some of the Internationale’s most westerly remaining bases in the Atlantic. However, notable syndicalist naval losses over the course of 1950 – with the evacuation of troops from Lagos causing significant strain on its own – had seen the reds’ position around the islands weaken. As a result, the Brazilians would take the lead in a joint operation that involved Canadian and American naval forces to launch an invasion of the islands. While the syndicalists had strong fortifications and well-stocked garrison, with the loss of control of the seas around the islands their positions were battered by the guns of allied battleships and relentless aerial sorties – allowing the Brazilian landing forces to overwhelm the beaches on the main island of Santiago and capture the city of Praia after just a few days of fighting. With the loss of Paia, the smaller defensive forces on the other islands of the archipelago soon began to fold – leaving them under firm Brazilian occupation by early July.

The capture of Cape Verde was vital to the wider war effort, with the Brazilians happily providing support for joint Canadian and American air and naval bases on the islands that placed them in an ideal position to support a larger attack on the syndicalist enclave in the West African mainland, and constantly threaten their supply lines running into Dakar to support it.

The American invasion began on 13 August, as a sizeable marine force landed in the far south-eastern corner of what was once Liberia. Fighting was hard from the first, with the syndicalists possessing a large army in West Africa numbering in the hundreds of thousands – including both low quality African forces and crack European troops – the reds defended fiercely as they attempted to stem the American advance and push them back into the sea, inflicting very heavy losses. For their part, the Americans poured troops wildly into the fray, despite the serious risks of a disaster on a grander scale than the previous year’s ill-fated Portuguese campaign if they failed to consolidate their foothold. Salvation and security would come after a month of fighting with the fall of Monrovia to the United States. Indeed, nearly two thirds of all American losses during the West African campaign were endured prior to the capture of the former Liberian capital.

The strategic importance of Monrovia in the West African theatre could not be overstated. Second only to Dakar as the most developed port in syndicalist West Africa, its loss both provided the American forces in the sector with their first truly secure supply line; it also made a syndicalist defence of the south eastern portion of the West African region untenable – with overland transport routes insufficiently developed and no other port offering facilities capable of sustaining such a large army for a prolonged period of fighting. As such, the syndicalists began a controlled withdrawal from back towards Dakar. This retreat would result in the surrender of the People’s Republic of Sierra Leone, which included both the former British and latterly German colony of the same name and once American-aligned Liberia, on 4 and Guinea on 14 October.

While the syndicalists had initially managed their retreat well, the breakdown in morale among their African troops – many of whom were reluctant to fight on as their homelands were abandoned – opened up gaps in the front that incisive American forces hoped to exploit. After piercing through the syndicalist lines to take control of one of the few well-developed roads in central Guinea – American armour raced northwards at breakneck pace to cut off a large force of 110,000 British, French, Spanish and Swedish leg infantry just shy of the relative safety of the Senegalese border at the end of October. Already exhausted from their retreat, and with attempts to break them out from syndicalist forces operating in Senegal quickly failing, these troops turned themselves over to the Americans at the beginning of November.

Even after this great victory in Guinea, fighting in the West African theatre was not yet finished with more than a quarter million syndicalist soldiers still in the field and hastily establishing defensive perimeters to protect the port of Dakar. Unfortunately for the reds, the Americans had learned lessons from past campaigns and made highly effective use of aerial and naval forces operating from bases in Cape Verde, Ghana and even the recently captured territory in Liberia to block off any possible evacuations out of Dakar and strangle the port’s fragile supply lines.

Short of the food, fuel and ammunition to sustain such a large force, and with morale in a desperate state, the syndicalists struggled to stabilise the front in the face of relentless American attacks and steadily conceded ever more ground as November wore on. The campaign would conclude on 26 November when, with the situation hopeless, the syndicalists surrendered. This was a grand victory, and effectively ended the Internationale’s global pretensions beyond Europe and the Mediterreanen. In total, the Internationale had lost around half a million men in the West African campaign, the large majority of them captured and a similar tally to the number lost in Nigeria-Benin earlier in the year. For their part, United States suffered comparable losses to that previous campaign, with the total number of casualties sustained through the war fast approached half a million – a heavy price for the liberation of a clutch of West African states that few Americans could point to on a map.

The arrest of Francis Yockey in December 1949 and the effective collapse of the Christian Nationalist Party saw a number of splinters from the old American extreme right split off into small and increasingly radicalised sects. These included adherents to Yockey’s own revolutionary nationalist Integralism in the Organisation of the New Revolution (ORN) – and also groups focused around the ideology of Christian Identity. This was a movement that had split off from British Israelism, a centuries-old religious sect believing that the British were descendants of the Ten Lost of Tribes of Israel and therefore a part of God’s Chosen People, around militant racial beliefs that saw all non-whites, and indeed those of outwith a Germanic and Celtic Aryan origin, as subhumans. It had gained notable traction in the 1930s and 1940s, aligning with the religious revivalism and highly charged racial climate of the time and become influential in the Christian Nationalist Party. Now, many adherents of Christian Identity had drifted towards the need for revolutionary terror to spark a third American revolution and race war.

While through 1950 these small factions radicalised at pace, the nature of their political evolution only came to the attention of mainstream America in August. After a summer of race riots and rising unrest throughout society, a Christian Identity militant group going by the name the Aryan Legion orchestrated the assassination of New York Governor Herbert Lehman. A Liberal and a Jew, Lehman’s very right to occupy the office of Governor had been challenged in the supreme court after his election in 1946 and he had remained a hate figure for many long afterwards – acting as a symbol for the extreme right of the failure of the Longist revolution in the 1930s. His murder shocked America and added to a growing sense of domestic chaos in the face of the nation’s titanic struggle with the Internationale.

As the spectre of political terror reared its head again in the United States, it was notable that despite syndicalism’s very recent militant history in the country and the ongoing war with the Internationale – no similar far left terrorist organisations emerged during this period.

As the nation looked towards the upcoming midterm elections, one of the most intriguing races was taking place in Illinois. Once the seat of American syndicalism, by the end of 1940s it had emerged as a key electoral battleground between an America First establishment based in proletarian Chicago and a Conservative-leaning hinterland. However, the state was also home to a fast-rising Liberal Party – with Eleanor Roosevelt recording her best vote share in the state outside of the North East and Pacific Coast at nearly a fifth of the vote. The character of the party here was quite distinctive compared to those other heartlands; with a more working class and egalitarian character and significant influence from reformed syndicalists in a state where Jack Reed won two million votes in 1936.

In early 1950, the Liberal Party establishment was upturned by the insurgent candidacy of progressive firebrand Paul Douglas – who won the primary to be the party’s Illinois Senatorial by a hefty margin. A leftwing Chicagoan economist, while never a true revolutionary in belief or inclination, he had provided his public support for the syndicalist movement during the 1930s and even briefly served in the bureaucracy of Jack Reed’s rebel administration in 1937 until the fall of his home city to the Longists early in the Civil War. Like so many in the Mid West who had chosen the wrong side in the fighting, Douglas spent years of his life in imprison and re-education, not being released until 1941 and only having his full constitutional rights restored later in the decade during the Taft administration. Since then, he had become politically active once more – joining the Liberal Party and campaigning on progressive social and economic causes. His campaign for the Illinois Senate found great success with a highly progressive stump demanding racial equality, civil rights for all, an end to the mistreatment of ex-syndicalists – which after years of growing more relaxed had harshened since America’s entrance into the Weltkrieg, and extensive redistributive programmes. Gaining momentum even after the primary, Douglas was assembling a broad coalition of Illinois’s large pool of 1940s non-voters (remarkably, fewer votes were cast in the 1948 election in Illinois than in 1936 – largely as a result of low levels of voting by Black and ex-syndicalist voters, even after the withdrawal of legal restrictions on their voting earlier in the decade) and disaffected supporters of the two major parties.

Douglas’ candidacy caused significant tremors both within and without the Liberal Party. Internally, many Liberals in other states – particularly its North Eastern heartland – were uncomfortable with the apparent confirmation of the accusations that had dogged the party since its foundation that it acted as a vehicle for the return of crypto-syndicalist politics into America that had caused such destruction in the 1930s. Meanwhile, the strength of his rhetoric, his ostentatious multiracial political rallies and overt campaigning in deprived Black neighbourhoods added to his air of radicalism. The party’s opponents went further, challenging Douglas’ constitutional right to stand for election on the grounds that his past syndicalist associations meant that he ran afoul of the constitutional bar on ‘un-American’ political candidacies. While the Illinois Supreme Court dismissed this case on the grounds that his past history was not relevant to his present platform, soon the issue was brought forward to the Federal Supreme Court. There, the Justices offered much less sympathy – ruling against Douglas, placing particular emphasis on past connections to Britain and France before the Civil War as evidence of the dangerous and un-American candidacy.

The Court’s ruling riled Liberals, nowhere more so than in Illinois itself, as they turned the Senatorial nomination over to Douglas’s wife Emily Taft-Douglas. Unlike her husband, her connections to 1930s syndicalism and active participation in the movement were much more muted; while, as a distant cousin of former Presidents Robert and Howard Taft, her family name alone provided some degree of protection from legal challenge – ensuring that her name would appear on the ballot.

Turquoise – America First hold

Dark Green – America First gain

Dark Purple – Conservative hold

Salmon– Conservative gain

Yellow - Liberal Hold

Pale Yellow - Liberal Gain

President Thurmond and his party had been prepared for a tough set of midterm results, even with the nation going to the polls in the context of the latter stages of a victorious campaign in West Africa, but despite this the scale of the Purple wave that swept over the nation – North and South, East and West – shocked even America First’s greatest pessimists. Hit by the biggest House swing since the collapse of the Democratic and Republican parties in the late 1920s and 1930s, dropping 69 seats; America First dramatically lost the Congressional majorities it had held since the outbreak of the Civil War and the decampment of loyalists to the Baton Rouge Congress in 1937. In the House vote, the party lost half of its remaining seats in New York and was swept out of New Jersey entirely. In the West, it lost every single seat beyond the Rockies with the exception of a small clutch around Los Angeles where it was organisationally strong. It also faced more modest but still damaging losses in the Mid West and even in the rock solid South with the Conservatives hammering them in Virginia, Florida, Kentucky in particular.

Meanwhile, just a decade after its formation, the Conservative party secured a healthy majority in the House of Representatives, a feet that had seemed scarcely possible even in the heady days half a decade ago when it had secured the White House by a whisker. The picture for the Liberals was more mixed. The party performed well in the big cities – gaining five seats across Los Angeles, Chicago and New York City, largely at the expense of America First in working class districts with large non-white populations who were mobilised who voted in unusually large numbers following concerted campaigning. However, this was balanced against significant losses in its New England heartlands to the resurgent Conservatives in a modestly weakened position relative to 1948.

Turquoise – America First hold

Dark Purple – Conservative hold

Salmon– Conservative gain

Yellow - Liberal Hold

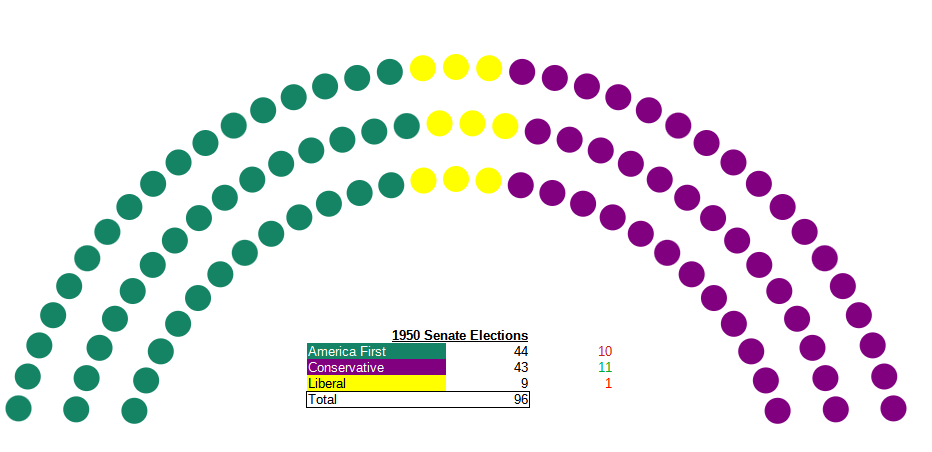

In the Senate elections, the swing was equally dramatic – with the Conservatives picking up no fewer than 11 additional seats. One of these came at the expense of the Liberals in Connecticut, but the other nine came from America First seats that the party had been able to win in 1944, the year of Robert Taft’s presidential election victory. These included shocking losses in states that Thurmond had won by large margins just two years before – including Florida, Kentucky and Missouri as well as William Fullbright’s impressive defence of Arkansas against the odds. The only seats America First held out in beyond their Deep South heartland were in Iowa, Pennsylvania and Indiana.

One of the most eagerly watched individual contests was in Illinois, where Paul Douglas’s wife Emily Taft-Douglas carried on the momentum of her husband’s campaign to drive the incumbent America First Senator, former Chicago Mayor Edward Kelly, into a humiliating third place even as she fell short of the victorious Conservative candidate, Everett Dirksen. Indeed, it was on the coattails of this campaign, that the Liberals cracked secured their first Congressional representation in the state as they flipped two House seats in Chicago.

While the House of Representatives elections had seen power shift entirely in the House, the Senate was now finely balanced. America First remained the largest party with 44 seats, just one more than the Conservatives, but they had lost their majority and were four seats short of controlling half the chamber – an effective working majority for the party holding the tie-breaking Vice Presidency.

With 33 of the nation’s 48 states holding gubernatorial races, it was also a bumper year in the struggle for power at a state level – which saw the same pattern of Conservative victories across much of the nation. However, with an unfavourable map that saw all sitting Liberal governors up for election, it was the leftwing party that suffered particularly badly as it was reduced to just two governorships – in Vermont and Rhode Island, with Herbert Lehman’s successor failing to retain control over the jewel in the party’s crown in the New York governor’s mansion.

As the new Congress was inaugurated in January, the Speaker’s gavel was turned over to a new figure who had now secured his place as one of the most powerful men in Washington, arguably second only to the President himself – John Bricker. Part of the Robert Taft’s Ohioan clique, Bricker owed his leadership position within the Conservative House delegation to his closeness to the former President and with it the established leadership faction within the party. However he was determined to make use of the power his party had won in Congress to push the Conservative agenda forward on a number of fronts – challenging the President’s authority in overseeing the war effort, America First’s centralist state and touchstone cultural issues, not least the increasingly unpopular and costly prohibition of alcohol.