Conquest of the Dahae

300-279 BCE

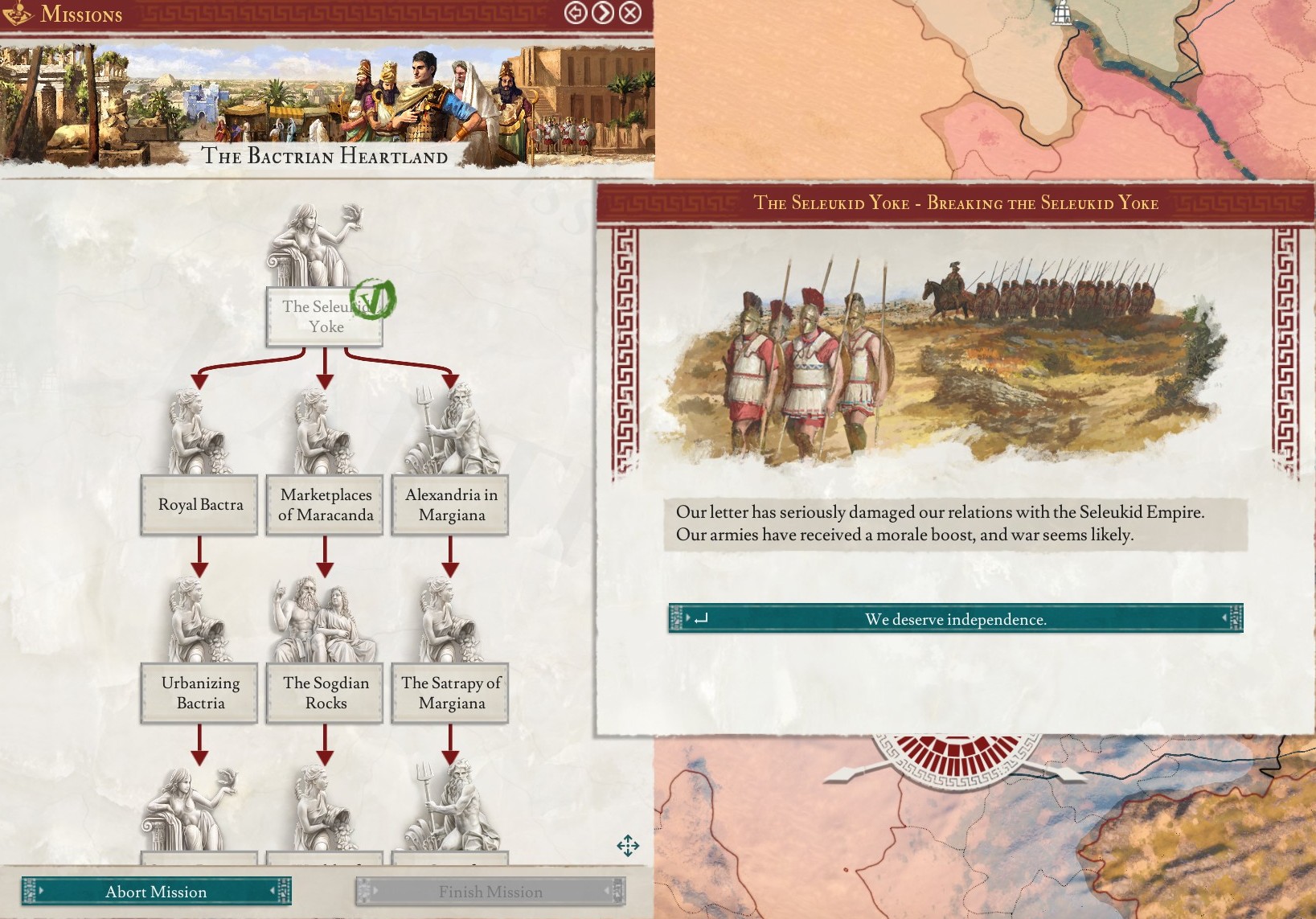

Only two years after the victory of the Seleukids, Sophytes shifted back onto the war path. After having secured the independence of Bactria as well as a southern foothold, he would spend the rest of his life warring to consolidate control of Central Asia and put an end to border raids perpetrated by their Scythian Neighbours.

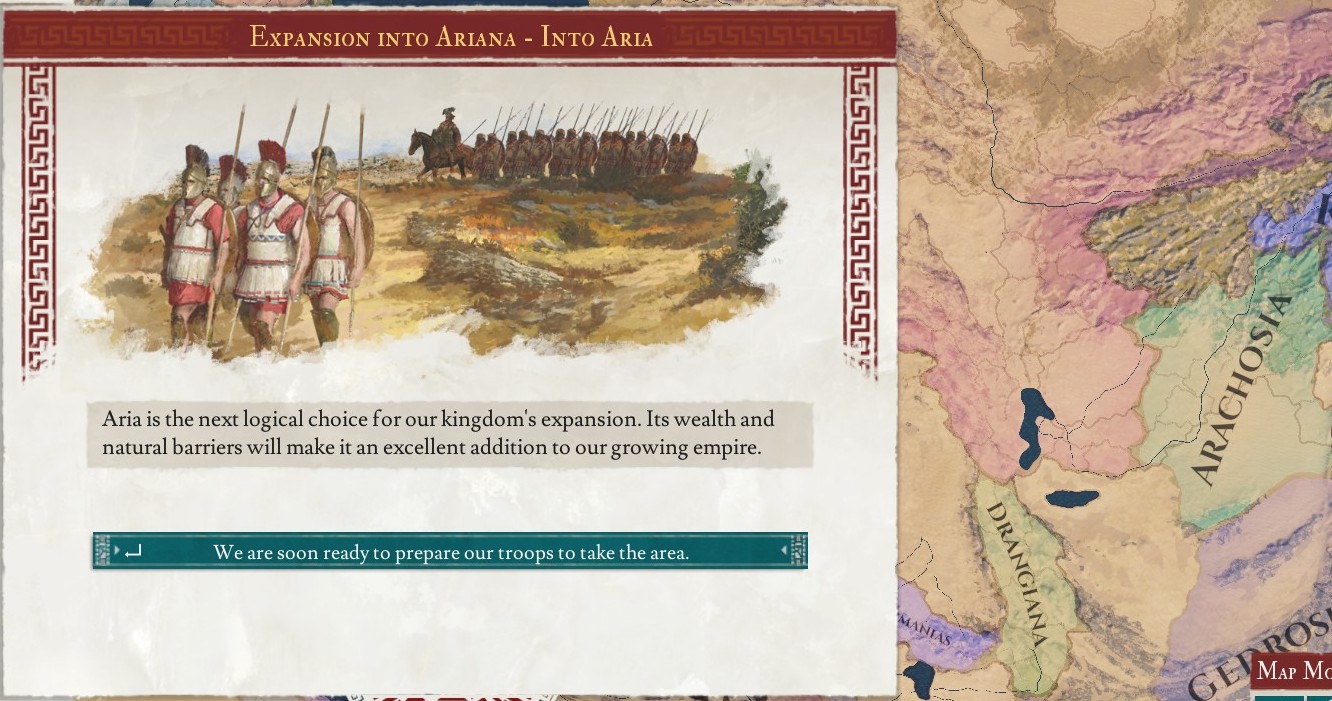

Sophytes would instead begin with the Kingdom of Tayaun which ruled over the rich Ferghana Valley. They had a similar history to Bactria, a region nestled in the mountains, with cities culturally dominated by greeks exiled by the Achaemenid empire, only to be later bolstered by Greek settlers brought by Alexander. Sophytes sent his armies marching north to seize their wealth and unite the greeks of Central asia.

The Bactrians split into three groups, with two beginning the siege of the cities of Kyropolis and Alexandria Eschate. The third guarded the passes to the south, stopping the Ionians from slipping into Bactria. The Ionians were wealthy and their cities were beautiful, but they did not have the force of arms to stop the Bactrians. Their cities were sacked and their nobility banished as the kingdom was annexed into Bactria.

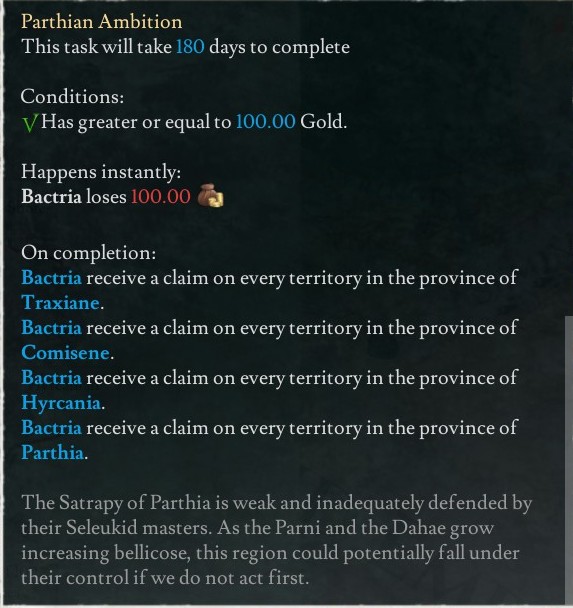

Then it came time for the Dahae nomads. They controlled the Steppe to the west of Bactria, occasionally launching small raids on their neighbors, but never amounting to anything more. Perhaps if they hadn’t been conquered, they could have built an empire of their own, but that would never come to pass. Sopytes launched a war against the three tribes of Kharesmia, Pissuria and Zantha.

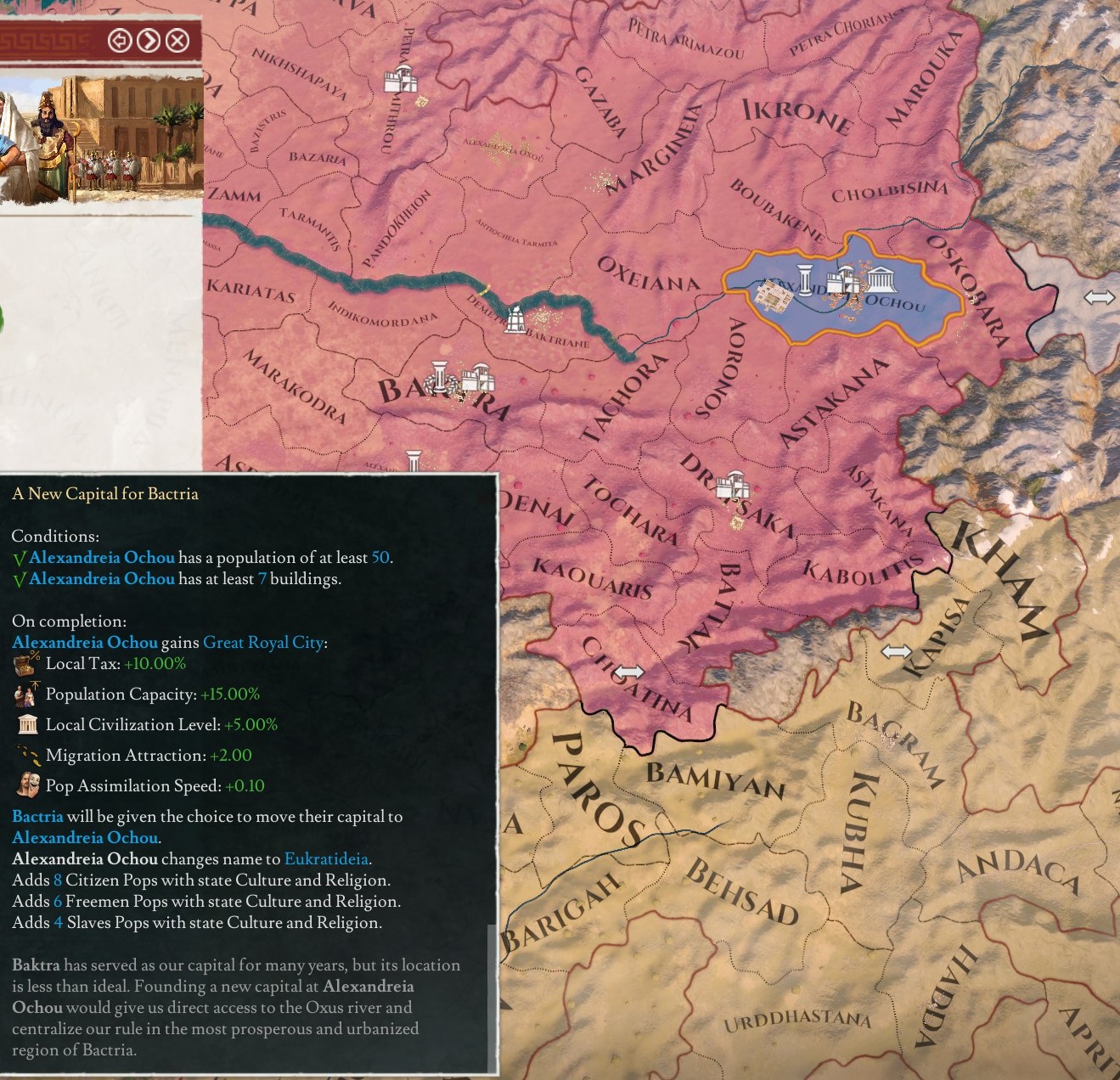

Part of his motivation was to take full control of the river Oxus. He would make an active effort to build cities all along the river, as well as develop the farmland and pastures of the region. But the other motivation was to put an end to the Dahae raiding. They threatened the cities of Bactria, and that could not be allowed.

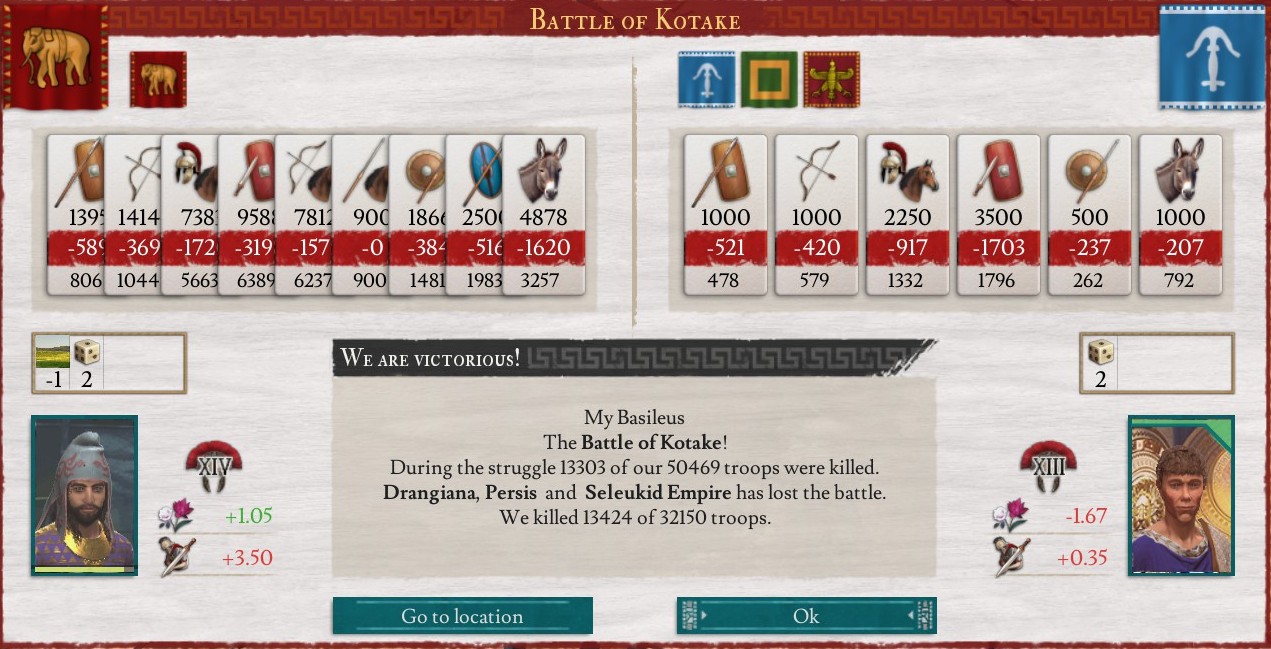

The war began, as Bactrian cavalry rushed down the Oxus river, taking control of Kharesmia, while a smaller force pushed into Pissuria. These two Dahae tribes were weak, and the Bactrians were able to quickly push aside their forces and siege down their forts. Pissuria was the first to fall, and Sophytes began a push into Zantha.

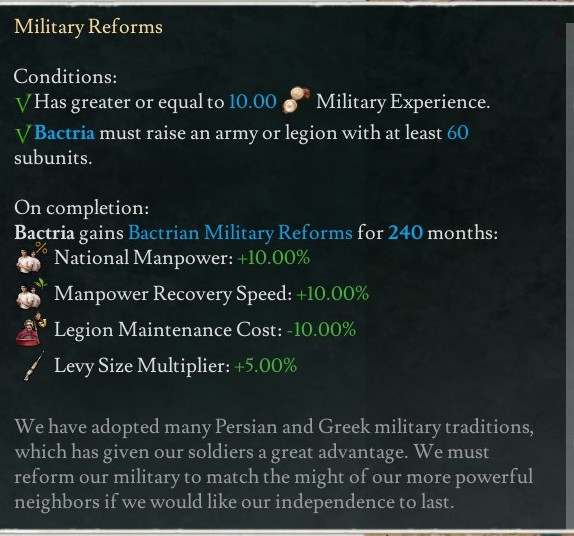

The Zanthians were a much harder fight for the Bactrians. The initial push into southern Zanthia was repelled. While the Bactrians brought Heavy Cavalry and Horse Archers to fight the Zanthians, they still struggled to defeat them in the open steppe. They had spent decades in the Hellenic sphere, and experience fighting other cavalry armies had grown scarce. Once the Kharesmians fell, the Bactrians launched a northern push, but once again the Zanthians rallied their forces north and pushed back the Bactrians.

Forced back, the Bactrians hired on Sogdian and Greek Mercenaries, before pushing into Zanthia in the north and south simultaneously. This time the Zanthians split their forces, and the Bactrians were able to use their superior numbers to overwhelm them. The Zanthians were defeated, leaving Parnia the last free tribe of the Dahae Nomads.

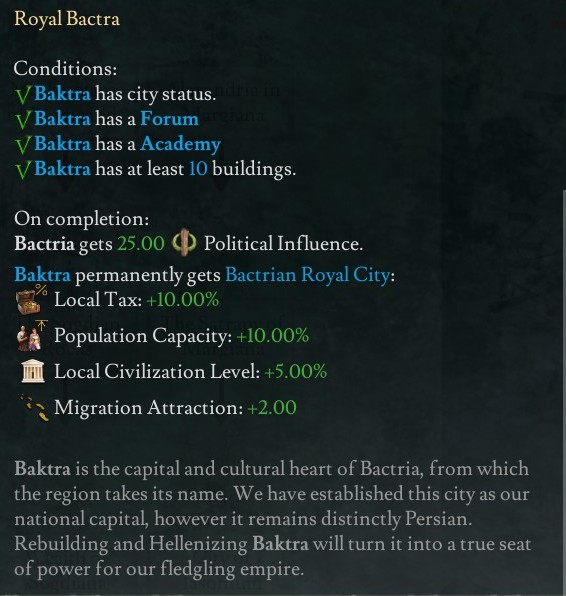

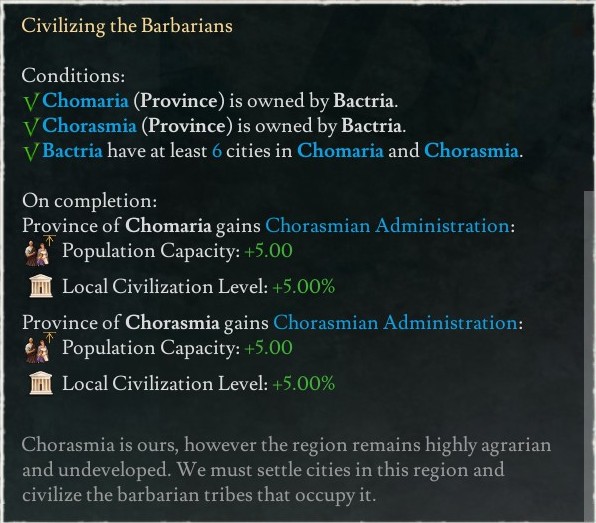

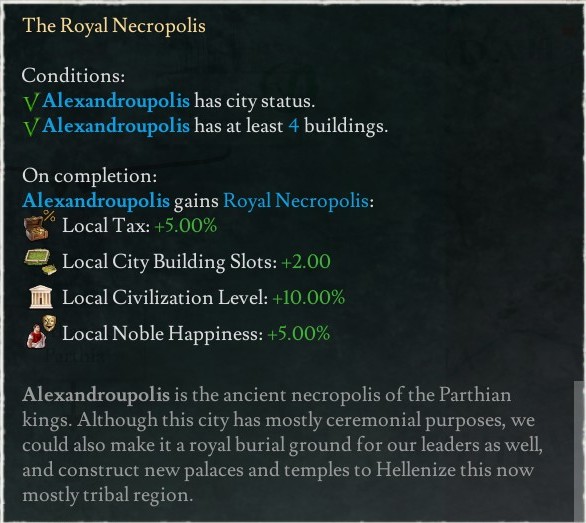

With the west secured and the Dahae pacified for now, Sophytes focused some time developing the conquered lands. Greeks and local Dahae were resettled in the lower Oxus to establish new cities. They would grow slowly, spreading down the river, from Bactra, eventually reaching the Aral Sea.

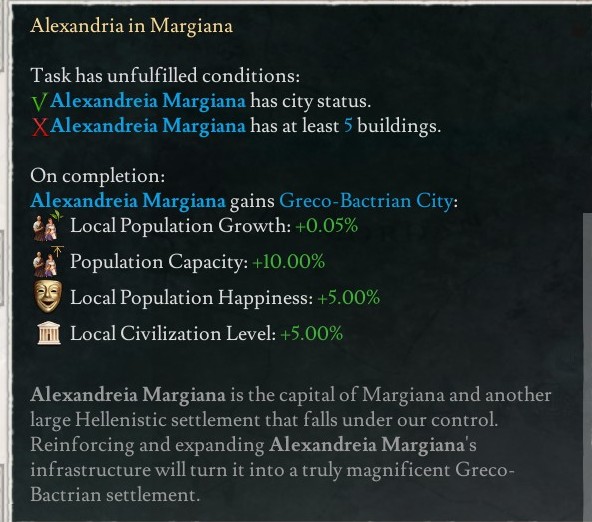

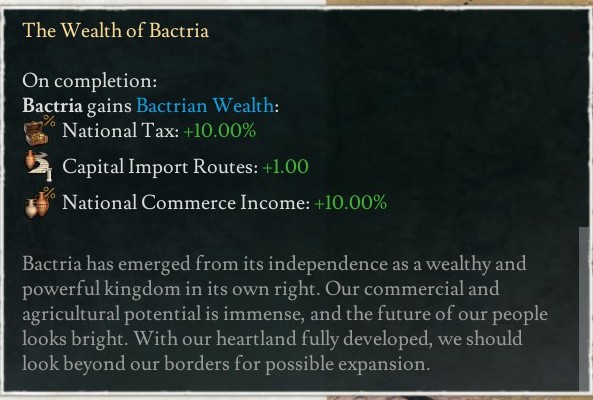

At the same time, new cities were growing in the Bactrian heartlands. These cities were dominated by Bactrians, rather than Greeks. These were not the first Bactrian cities, but unlike the older Bactrian cities, Greek influence could be seen in the architecture. The growing urbanization of Bactria would rapidly expand the economy and fill the Kingdom’s coffers, but it would also create a growing demand for more food.

But before the farms of Bactria could be expanded, Sophytes began the second and final phase of his war against the Dahae. He sought to push the border above the Central Asian desert and conquer the last of the Dahae. This put the Kingdom in a war against the Parnian and Attasian Dahae, as well as the Scythian tribe of Yancai, which had pushed into the Dahae lands after their defeat at the hands of Bactria.

This time, the Bactrians made a united push, and the combined Scythian and Dahae armies were unable to stop them. The Bactrians directly assaulted their fortifications and pushed aside their armies as they took control of the land and established a new border.

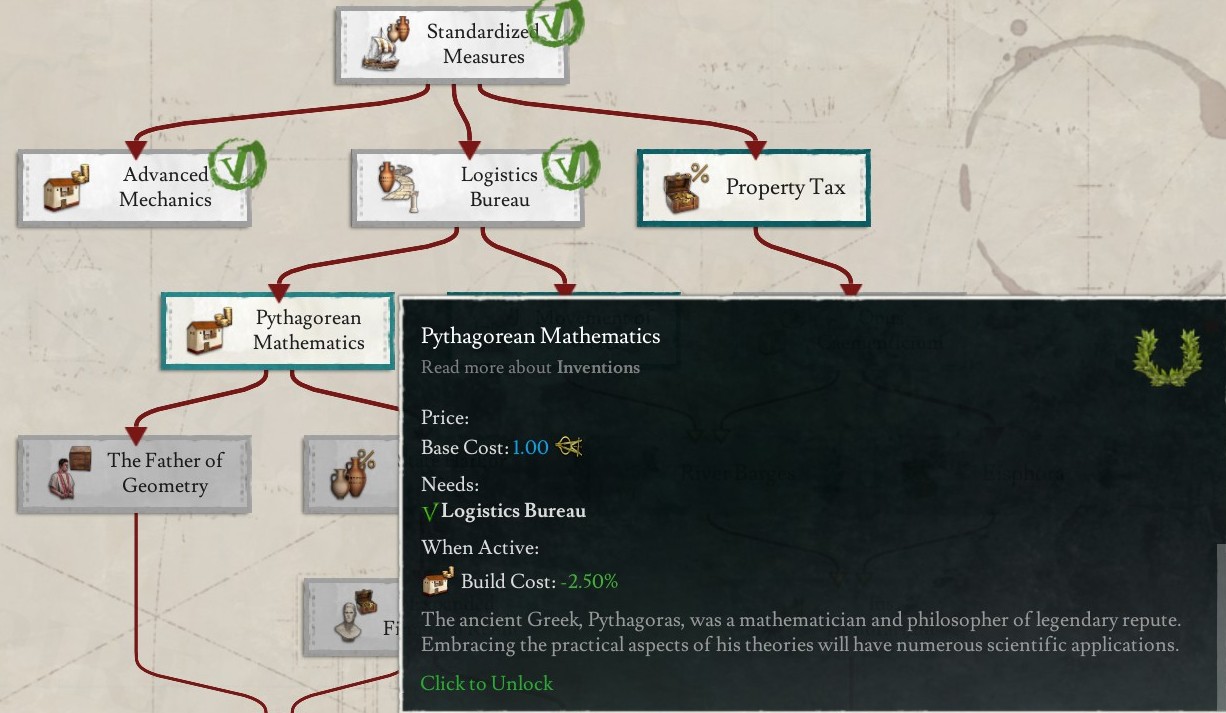

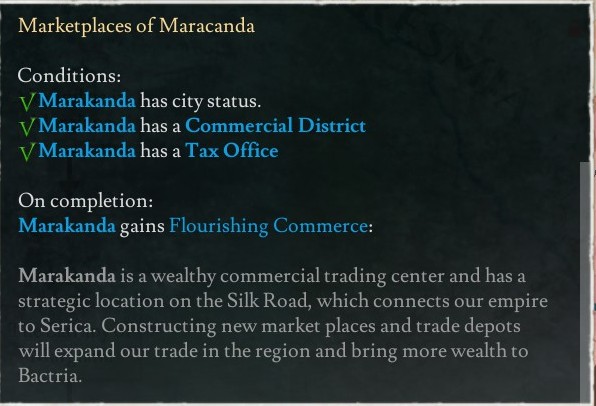

The loot taken from conquering the Dahae lead to a spike in the development of Ferghana. Trade was stimulated, expanding the northern markets, through which the silk road passed. At the same time, Sophytes invested in the administration and capacity to tax their newfound wealth.

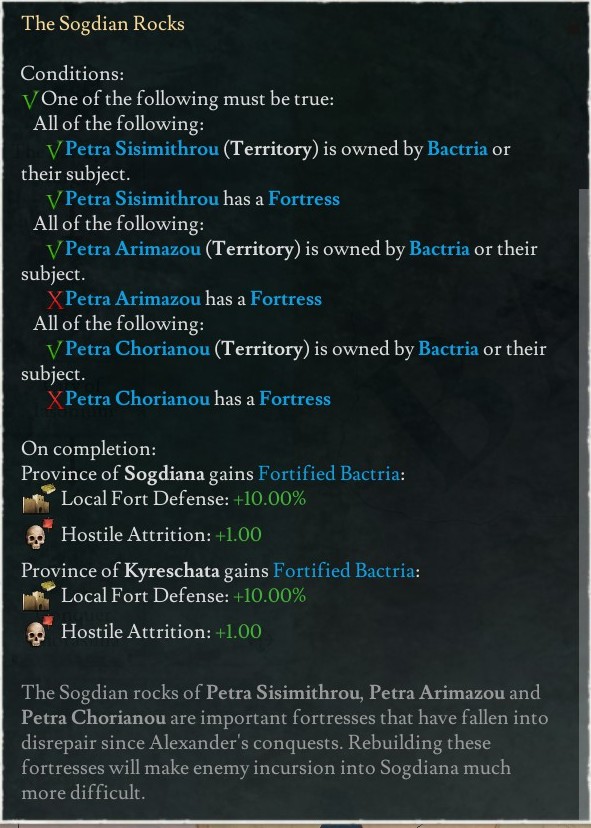

The remainder of the windfall went to fortifying the southern border with the Seleukids and Maurya. Those two empires served as major rivals and threatened Bactria, as its newfound wealth was inspiring jealously in its southern neighbours. The threats posed by the Northern Scythian raiders were minor in comparison to the threat of conquest.

The rapid conquest of the Dahae, following the expansion in the east had destabilized Bactria, and even as the cities in the east grew in wealth and power, the conquered Dahae grew restless. This led to a period of small rebellions that had to be put down by the Bactrian military. The first of which took place in the conquered region of Parthia. The rebelling Parthians were vastly outnumbered, and fell without much note, except for the pillaging of their lands a second time.

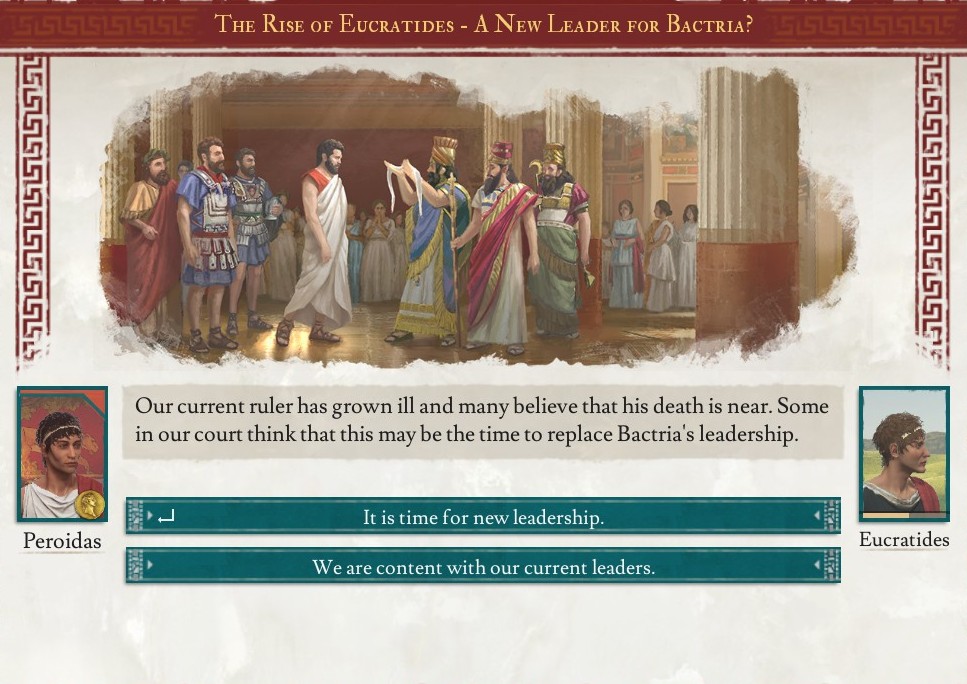

Shortly after the Parthian rebellion, Sophytes died of an unnamed illness, leaving the Kingdom to his twelve year old son, Periodas. Shockingly, despite his youth and the chaos of Bactria, he retained the throne after succession. His father had built up a wide coalition of supporters, amongst the Bactrian and Greek nobility, whose support kept the Kingdom from collapsing into a civil war.

On his fourteenth birthday, after his rule had been secured, the court Oracle began proclaiming doom, should Periodas continue to reign. The Oracle was removed, and grand sacrifices were held to appease the gods, and reassure the population. But rumors and stories of inevitable doom continued regardless, which only spread fear throughout Bactria.

Even the Ionians began to revolt as news of the prophecy spread. They banded together with the Sogdians and the entirety of the Ferghana valley rose up in revolt to secede or replace Periodas as King. Once again, they simply had far too few soldiers to face down the royal army of Bactria, but their revolt damaged the Ionian cities and threatened famine as farmlands were burned or left vacant.

The final rebellions took place in the east, as the Dahae rose up. First in the south under Pissuria, then again in the north under Parnia. These uprisings were disorganized, and the tribes were far weaker than they had been when Bactria had conquered them. They fell just the same as the other rebels, and the Kingdom finally began to move towards stability.

With the return of peace, farms began to expand and develop in Ferghana and along the Oxus. Pastures were expanded, and improved with more secure fencing, while farmland was cleared and plowed. This worked to bring down food prices and allow the cities to continue to grow unimpeded. The cities of Ferghana and Bactria flourished, while Sogdiana was rapidly becoming a core part of the Kingdom.

In the South, the mining industry expanded to help feed the growing demands of the Kingdom. The Goldmines were expanded to enable the minting of more coins, while Iron mines armed the military and allowed cities to produce more tools for artisans and farmers. As merchants traveling along the silk road spent more time in Bactria buying and selling their goods, the Lapis Lazluli mines expanded to meet the demand for dyes.

With the East secure, Periodas sought a victory to secure his reign. The Scythians to the north were able to raid Sogdia, and now that it had grown so far in wealth, protecting them became a priority. The Scythians like the other tribes of Northern Asia were outmatched by the Bactrian cavalry, and they forced the border north, where raiders could be stopped in mountain passes or along the river.

To secure their position against the Seleukids, Periodas sent diplomats across the Caspian sea to speak with the Armenian King. They would organize an alliance to counter their common foe, fully securing the southern border against threat. Of course, the eastern border with Maurya was still a concern. The wealth and power of India was yet unmatched, except perhaps for rumors of Serica in the far east.