Part V

Part V: The New Standard Program

June 1937

"She's going to rule the seas."

Comments made by Ram Dass Katari,

Minister of the Navy, upon seeing the

designs for HMIS Vikrant

in April 1937

-------------------------------------

Despite the chaos that resulted from the attempted assassination of Mahatma Gandhi, the Indian government continued its program of expanding its major shipyards. Unlike most other government projects, which found themselves without any funding during the period, the maritime technological and industrial expansion program continued unabated. The Indian National Army made its disgust known over this decision, especially since its soldiers were fighting and dying with too few reinforcements and antiquated weaponry. One divisional commander, Bernard Montgomery, even resigned in the middle of the crisis over what he saw as the mismanagement of government funds. The loss of the popular commander severely hindered efforts to suppress the rebellion. The entire funding incident left bad blood between the two services that continues to the present day.

By the middle of 1937, however, the rebellion had been suppressed and the shipyard expansion program had been completed. The debate that had ended inconclusively over a year earlier now returned as Rajendra Prasad and the Indian government turned to the issue of rearmament. The positions of the different factions had changed little during the recess. Most Indians still called for a navy of light warships and a primarily infantry-based army that could better defend India. British officers on loan pushed for a military that would be able to assist the empire in the event of war, which meant capital ships for the navy and motorized infantry and tanks for the army. Such a military would be much smaller than that planned by Indian officers. The officers of the Royal Indian Air Force simply sat quietly, knowing that it would become a subsidy of whichever branch won the bulk of the government's funding.

On June 18th, 1937, after delaying as long as possible, the major officers and civilian leaders of the armed forces gathered together in Delhi to witness the unveiling of the rearmament plan. When the Minister of the Navy, Ram Dass Katari, walked to the center of the room to announce the plan, an audible groan came from the army officers, who knew the plan would almost certainly favor the Royal Indian Navy. The minister's introduction confirmed the impression. Stating that India's destiny rested on international commerce, he described her need for a navy to defend that commerce. With her long border, a defense of the frontier by the army would be too expensive to maintain while leaving India's source of wealth open to enemy attack. Thus, India would place its hopes on a navy.

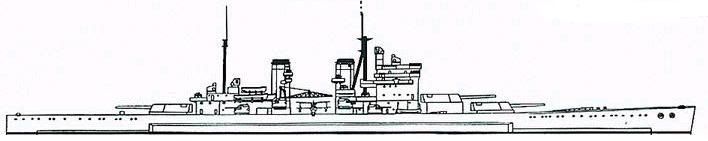

The proposed armament plan was called the New Standard Program. At its heart, lay three massive capital ships: two battleships and an aircraft carrier. The battleships, the

Taragiri and

Vindhyagiri, displaced 40,000 tons with a length of nearly 230 meters and a beam of about 30 meters. They were to be capable of 30 knots at full steam and were to be armed with ten 14-inch guns in two triple and a quadruple turret. The naval ministry had debated equipping them with 15-inch guns, which would significantly increase their firepower. The cost, however, would be prohibitive. India possessed a numer of 14-inch coastal guns that could be disassembled and used on the

Taragiri-class battleships, while the 15-inch guns would have to be constructed from scratch. Even so, with a crew of 1500 men, they were the equal of any vessel in the region.

Line Drawing of the Taragiri-class Battleship

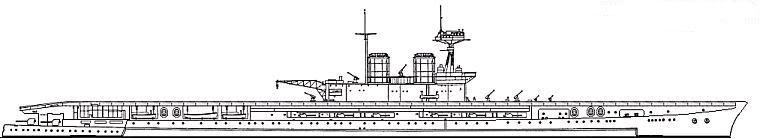

To complement the two battleships, the Royal Indian Navy would feature a fleet carrier. This carrier,

HMIS Vikrant, would carry between 60 and 80 aircraft. She would be capable of 30 knots, enabling her to keep up with the battleline. The vessel would displace 20,000 tons. Her length and beam would measure 240 and 28 meters respectively. The

Vikrant was envisioned for two roles. First, she would be a scouting unit for the battlewagons, a necesity given the large area to be covered by the RIN and its small size. Secondly, Ram Dass Katari intended for her to be a testing platform for his new and radical ideas on carrier warfare. Her air group would be composed largely of torpedo planes intended to destroy enemy fleets. The idea had firm support from the ranking officer of the Royal Indian Air Force, Frederick Bowhill.

Line Drawing of the Vikrant-class Carrier

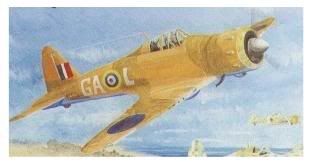

In regards to cost, the

Vikrant would be much cheaper than either of the battleships. The air group would slightly increase her pricetag, but not significantly. Recently, in the United Kingdom, Gloster had produced a prototype fighter, the F.5/34. The aircraft was to be a long range fighter to replace the Gloster Gladiator. The Royal Air Force, however, decided on another design, the Hawker Hurricane. Having already spent money on research and development, as well as a pair of prototypes, Gloster was desparate to find a buyer. The Royal Indian Air Force and the Royal Indian Fleet Air Arm could purchase the fighter quite cheaply. Since Gloster had several factories in India, the money would even stay in the Indian economy; it was an ideal situation. Ram Dass Katari's torpedo planes would be more expensive but the overall cost for the air groups would be much less than anticipated.

Conceptual Drawing of a Gloster F.5/34 Fighter

The New Standard Program also planned the construction of several lighter warships for screening purposes. Three light cruisers, as yet unnamed and undesigned, would support the battleline. The vessels were to be capable of 30 knots and would be armed with at least eight 6-inch guns but no other details were available. Construction on these warships wouldn't begin until 1938 at the earliest. Furthermore, the fleet would have the support of no less than 20 destroyers, displacing 1500 tons and equipped with five 4.5-inch guns. As with the light cruisers, construction wouldn't commence for at least a year. Altogether, the New Standard Program anticipated the completion of a fleet of twenty destroyers, three cruisers, an aircraft carrier, and two battleships by the middle of 1940.

Had the presentation ended there, the room would have erupted in riot. The navy was clearly one intended for operations in either the Mediterranean or the South China Sea; in other words, intended for the defense of the Commonwealth rather than India. The plan would not leave much if any funding for the army, meaning that India would have nothing but the current two divisions of the Indian National Army for defense. As if in ignorance of the growing anger in the room, Ram Dass Katari calmly removed the presentation card displaying the design of the

Vikrant and replaced it with another, reading "New Standard Tentative Program." Intruiged, the shouts of dismay stopped before they could begin.

The New Standard Tentative Program at the time was not as formalized as the New Standard Program, essentially the second phase of that armament plan. It would entail expansion of the army as well as the navy. Unlike the New Standard Program, the heart of the naval portion of the Tentative Program was not the battleship but the carrier. The two

Taragiri-class battleships would absorb a disproportionate amount of the Indian economy. Additional battleships would cripple the economy. At best, the New Standard Tentative Program could expect either a small battleship or a battlecruier. Ram Dass Katari called for a force of three

Vikrant-class carriers for the new plan, which would function as its striking rather than scouting arm. A number of cruisers and destroyers would also be constructed to support the force, but their numbers would depend on whether or not the New Standard Tentative Program would include a battleship. Either way, this second wave of construction would function as a fleet for the Indian Ocean.

The Tentative Program also included an auxiliary building plan. Construction of this force would probably not begin until 1941 at the earliest and was intended to be a long range Pacific striking group. At its heart would lay the aviation cruiser

HMIS Garunda and an as yet undesigned heavy cruiser. Several destroyers, displacing 1500 tons, would support the battle group. The force would accompany what Ram Dass Katari labelled a fast amphibious assault transport. More accurately, it was a passanger liner that France was looking to sell that could be hastily converted with light armor and anti-aircraft guns. The vessel would carry a full division of troops. Together, the task group would sail through the Pacific in the event of war with Japan, attacking convoys and seizing lightly protected islands. Alternatively, it could be used to ferry troops to south east Asia or Australia if needed.

The army would receive a major overhaul with the New Standard Tentative Program. An armored division composed of a new infantry support tank would be assembled. The tank was slow, but heavily armored and deadly against enemy infantry. Future infantry divisions would also receive supporting battalions of these tanks. A number of infantry divisions would be mobilized as well. The final number had not yet been determined, but it would be no less than six and almost certainly much higher. The armored division and two or three of the infantry divisions would be based in Bombay along with the bulk of the New Standard Program vessels, sending a clear signal that they were intended for action in the Mediterranean. The rest of the units would take up positions along the border or in major cities like Calcutta. As with the rest of the New Standard Tentative Program, mobilization would not commence until 1940.

The final element was the Royal Indian Air Force. Unlike its British counterpart, it knew that geography would never permit it to become the dominant service of the Indian military. The Indian border was simple to rough to permit successful aerial interception of an enemy invasion. Still, the RIAF would grow to about 300 aircraft under the new program. Perhaps as a form of compensation to the much ignored service, the RIAF was not forced to adopt Gloster F.5/34 fighters. The RIAF quickly let it be known that it looked for a modified version of the Hawker Hurricane. Armed with 20 mm cannons rather than the .303 machine guns of the standard model, the Indian version would have some ground attack capabilities rather than being solely an interceptor.

When Ram Dass Katari sat down, the room was moderately satisfied. The navy was the clear winner. The army and the air force were were unhappy but relatively content since they had received more than they had anticipated after the unveiling of the

Taragiri. Niether Indian nor British officers were completely displeased as the New Standard Programs balanced Commonwealth and Indian interests. The New Standard Programs were certainly ambitious and would take several years to complete yet, when finished, it would make India the dominant player in the region.