The second hour," said Nicephorus, "is already past. The solemn procession to the church is about to take place. Let us now do what the hour demands. At a convenient time we will reply to what you have said."

May nothing keep me from describing this procession, and my masters from hearing about it! A-numerous multitude of tradesmen and low-born persons, collected at this festival to receive and to do honor to Nicephorus, occupied both sides of the road from the palace to St. Sophia like walls, being disfigured by quite thin little shields and wretched spears. And it served to increase this disfigurement that the greater part of this same crowd in his (Nicephorus') honor, had marched with bare feet. I believe that they thought in this way better to adorn that holy procession. But also his nobles who passed with him through the plebeian and barefoot multitude were clad in tunics which were too large, and which were tom through too great age. It would have been much more suitable had they marched in their everyday clothes. There was no one whose grandfather had owned one of these garments when it was new. No one there was adorned with gold, no one with gems, save Nicephorus alone, whom the imperial adornments, bought and prepared for the persons of his ancestors, rendered still more disgusting. By, your salvation, which is dearer to me than my own, one precious garment of your nobles is worth a hundred of these, and more too. I was led to this church procession and was placed on a raised place next to the singers. ...

"But tell us," they continued, " does your most holy master wish to close with the emperor a treaty of friendship through marriage?"

" When I came hither he wished it," I said, " but since, during my long delay, he has received no news; he thinks that you have committed a crime, and that I have been taken and bound; and his whole soul, like that of a lioness bereft of her whelps, is inflamed with a desire through just wrath to take vengeance, and to renounce the marriage and to pour out his anger upon you,"

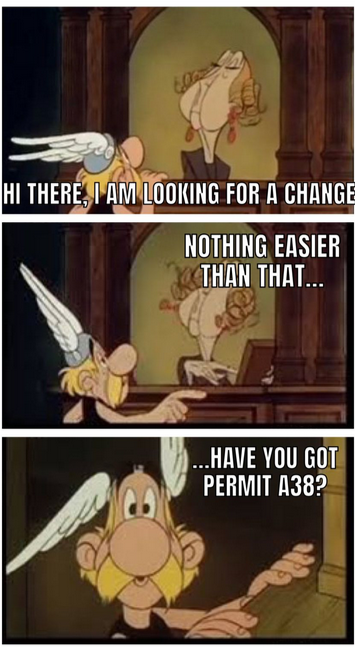

"If he attempts it," they said, " we will not say Italy but not even the poor Saxony where he was born - where the inhabitants wear the skins of wild beasts-will protect him. With our money, which gives us our power, we will arouse all the nations against him; and we will break him in pieces like a potter's vessel, which, when broken can not be brought into shape again. And as we imagine that Al thou, in his honor, hast bought some costly garments, we order you to bring them before us. What are fit for you shall be marked with a leaden seal and left to you; but those which are prohibited to all nations except to us Romans, shall be taken away and the price returned."

When this had been done they took away from me five most costly purple stuffs; considering yourselves and all the Italians, Saxons, Franks, Bavarians, Swabians-nay, all nations-as unworthy to be adorned with such vestments. How unworthy, how shameful it is, that these soft, effeminate, long-sleeved, hooded, veiled, lying, neutral gendered, idle creatures should go clad in purple, while you heroes-strong men, namely, skilled in war, full of faith and love, reverencing God, full of virtues-may not! What is this, if it be not contumely? "But where," I said, "is the word of your emperor, where the imperial promise? For when I said farewell to him, I asked him up to what price he would permit me to buy vestments in honor of my church. And he said: "Buy whatever ones and as many as you do wish;' and in thus designating the quantity and the quality, he clearly did not make a distinction as if he had said 'excepting this and this.' Leo, the marshal of the court, his brother, is witness; Enodisius, the interpreter, John, Romanus, are witnesses. I myself am witness, since even without the interpreter, I understood what the emperor said."

"But," they said, -these things are prohibited; and when the emperor spoke as you say he did, he could not imagine that you would even dream of such things as these. For, as we surpass other nations in wealth and wisdom, so also we ought to surpass them in dress; so that those who are singularly endowed with virtue, should have garments unique in beauty."

"Such a garment can hardly be called unique," I answered, " when with us the street-walkers and conjurers wear them."

"Where do they get them? " they asked.

"From Venetian and Amalfian traders," I said, " who, by bringing them to us, support themselves from the food we give them."

"Well, they shall not do so any longer," they said. They shall be closely examined , and if any thing of this kind shall be found on them they shall be punished with blows and shorn of their hair."