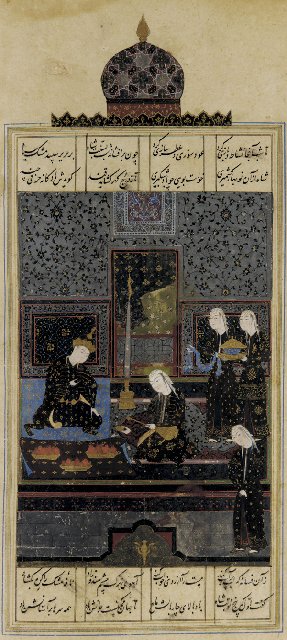

4.4 THE KIDARITE KINGDOM IN THE V c. CE.

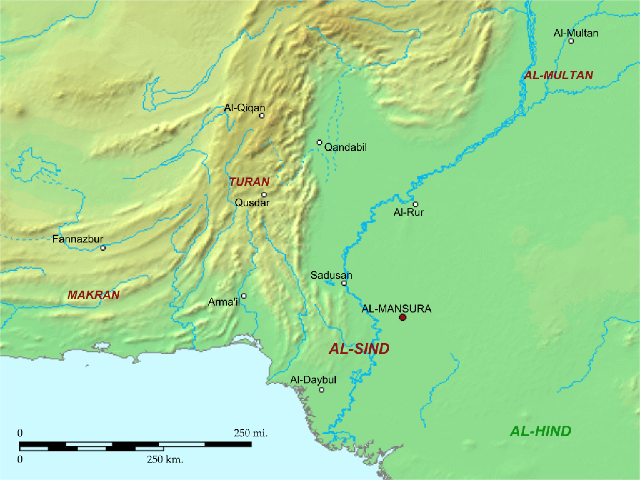

No ancient historians covered the kingdom that the Kidarite Huns established in Central Asia, despite the fact that it lasted for a century and put against the ropes two powerful empires:

Ērānšahr and the Gupta Empire in India. In the absence of reliable written sources, we are forced to rely on several alternatives that put together can let us draw a rough sketch of thus key period in the history of Central Asia:

- Indirect references in other historical sources: the Armenian chronicles of Movsēs Xorenac’i and Łazar P’arpec’i, the Perso-Arabic tradition as transmitted by Ṭabarī and other Islamic authors who derive their material ultimately from the Xwadāy-Nāmag tradition, and some rare accounts in Greek sources, basically in the fragments of the lost works of Priscus of Panion. Some fragments in Syriac texts contain also valuable information.

- Numismatics (including seals and bullae).

- Epigraphy and photographical studies.

- The travel accounts of several Chinese Buddhist monks who traveled to India by land from Central Asia (Faxian and Song Yun).

- Archaeology.

- Chinese dynastic stories (the Wei Shu and Tongdian) which cover political events that affected the courts of some Chinese dynasties in this period, among them official embassies.

This list gives an idea of the nature of the work of putting together a history of the Kidarites; it is like working on a jigsaw puzzle without a plan and without knowing how many pieces should be there. With the added difficulty (for professional historians) that these sources cover several academic disciplines (textual studies, numismatics, archaeology) and several ancient languages (Greek, Armenian, Syriac, Middle and New Persian, Arabic, Bactrian, Sogdian, Sanskrit and several Indian dialects like Gandhāri, and Middle Chinese) as well as several scripts (Pahlavi, Greek, Syriac, Bactrian, Arabic, New Persian, Sogdian, Chinese, Brāhmī and Gupta). Due to the nature of academics and the limitations of human life and intellect, it is impossible for a single individual to cover all these disciplines, so it is necessary to cover many different secondary sources in order to get a picture as complete as possible, integrating all of them into a single comprehensive unity.

Silver drahm of Kidāra. Notice how the design keeps the fire altar with two attendants on the obverse typical of Sasanian coinage.

Detail of Kidāra’s portrait on the drahm above, which differs sharply from the traditional image of Sasanian kings.

Of all these sources, numismatics has showed itself to be really important, to the extreme that without the discovery and study of ancient coins, it would have been impossible for historians to confirm the historicity of the account by Priscus of Panion about the “Huns whom they call Kidarites”. But although valuable, they also have their limits. As I explained in a post in the previous thread, proper Kidarite coinage began appearing in the 370s CE bearing the bust of a king named

Kidāra, but all the subsequent coinage issued by the Kidarites follows exactly the same pattern, with the same bust and with the same name. Another coin type (classified by the Austrian numismatist Klaus Vondrovec as “type 16”) carries the name of

Varā Saha (“King Varā”), who might be a later authority of the Kidarites. This means that for the whole Kidarite period (practically a whole century) we only know the name of two rulers through the coinage. In that same post I also mentioned a clay

bulla found in Swāt (northwestern Pakistan) with the effigy of a Kidarite king. But unfortunately, that one example was broken exactly at the point where the name of the king should have been. Fortunately, two more examples of bullae made with the same sealing have appeared, and in them the name of the king is fully legible in the Bactrian legend as

Ularg:

Lord Ularg, the King of the Oghlar Huns, the Great Kušān King, the Afšiyān of Samarkand.

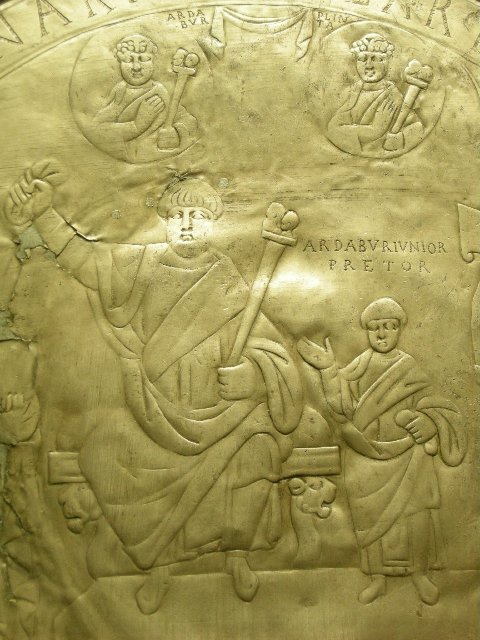

Thus, we know already the names of two Kidarite kings, but it is obviously still not enough. Priscus of Panium wrote that the last Kidarite king, who lost the final war against the Sasanian king Pērōz (who was allied with the Hephthalites) was

Kunkhas (Greek

κουνχας), a name that many historians suspect was not a proper personal name but a title, perhaps a corruption of “Khan of the Huns”, or “Hunnic Khan”, corrupted by the translation from “Hunnic” (or Bactrian) into Middle Persian and then into Greek. That is as far as we can arrive in our reconstruction of the names of Kidarite kings, resorting to all the available sources.

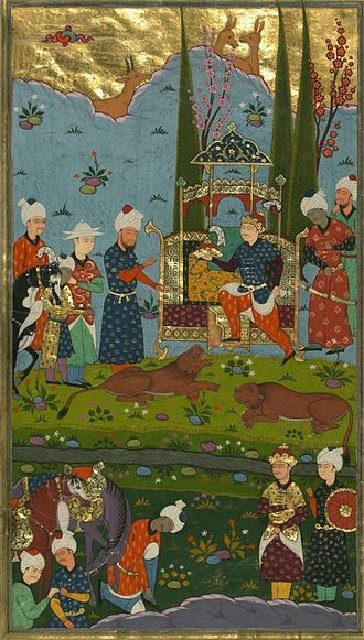

The Kidarites also appropriated Kayanian ideology (which as we have seen was first adopted by the

Kušān Šāhs) The presence of the title of

Kay in their coinage, first appearing on imperial Sasanian coins on a stable basis during the reign of Yazdegerd II (438–457 CE), led Vondrovec in 2014 to suggest a

terminus post quem for the whole of the series of 438 CE to match the beginning of the rule of Yazdegerd II. But as we have seen, actually the title Kay appears already on some coins issued by Šābuhr II. Additionally, as Rezakhani points out, the assumption that the direction of cultural borrowing is necessarily from the Sasanians to the Kidarites is historically unreasonable and assumes a hegemony on the part of the Sasanians which in fact did not exist. Borrowings from East Iran to West Iran, particularly in terms of iconography and ideology, are well known and documented. It is thus possible that

Kay was a known title of the eastern dynasts, being borrowed and used by the Sasanians in their process of absorbing the political power of the Kushano-Sasanian and Kidarite dynasties.

Some Kidarite coins have been found bearing names of kings hitherto unknown to historians and which are therefore impossible to date with any precision. This silver Kidarite drahm bears the name “Buddhamitra” and is vaguely dated to the “IV-V c. CE”.

The coins and

bullae confirm that the Kidarite kings assumed the title of “Kushan Kings” (or “Great Kushan Kings”) in a deliberate manner, trying to claim legitimacy to rule over ell the territory that was once controlled by the “real” Kushans and the Kushano-Sasanian kings. And this also is reflected in how other countries saw and named them. The Armenian chroniclers P’avstos Buzand and Ełiše use the name

K’ušan systematically to refer to them. And the same is true for the Chinese sources. Thus, according to the

Wei Shu:

The king of the Great Yuezhi called Jiduoluo, brave and fierce, eventually dispatched his troops southwards and invaded Bei Tianzhu (northern India?), crossing the great mountains to subjugate the five kingdoms which were located to the north of Gandhāra.

The Japanese historian Shoshin Kuwayama proved in 2002 that

Jiduoluo is the Chinese rendering of

Kidāra, and thus that this part of the

Wei Shu is a brief account of the Kidarite conquest of Gandhāra (as we saw in the previous thread). The Chinese sources talk about the same political entity as the Armenian Kushans but conflate them with the usual grouping of this population under the rubric of the

Da (“Greater”)

Yuezhi. According to the

Wei Shu:

The Da Yuezhi country, of which the capital had been situated at Lujianshi city, lies to the west of Fudisha (i.e Badaḵšān), 14,500 li away from Dai (the capital of the Wei dynasty). In the north it touched the Ruanruan, which invaded (the Da Yuezhi) so many times that the Yuezhi had at last to move the capital westwards as far as Boluo city, 2,100 li away from Fudisha (i.e. Badaḵšān). The King Jiduoluo (i.e. Kidāra), who was a brave warrior, at last organized troops and marched to the south to invade Northern India, crossing the Great Mountains (i.e. the Hindu Kush), and completely subjugated five countries to the north of Qiantuoluo (i.e. Gandhāra).

The Xiao Yuezhi have their capital at Fulousha (i.e. Puruṣapura, modern Peshawar). The King was originally the son of Jiduoluo, king of the Da Yuezhi. Jiduoluo was forced to move westwards by the attack of the Xiongnu and later made his son guard this city. For this reason, the kingdom was named the Xiao Yuezhi.

The same source further tells us that the king of the Xiao (Lesser) Yuezhi, determined by scholars to be in the area of Gandhāra, is the son of the king of the Da (Greater) Yuezhi. Previous scholars have noticed the similarity between this narrative of the rise of the Kidarites/Da Yuezhi and those provided in much earlier sources (i.e. the

Hou Hanshu) for the rise of the original Da Yuezhi tribe. These were the tribe who, hundreds of years earlier, had migrated westwards into Transoxiana and Bactria as the result of the onslaught of the Xiongnu. In 2007, Elizabeth Errington and Vesta Sarkosh Curtis suggested that the

Wei Shu is “echoing” the accounts in the

Hou Hanshu of the rise of the Yuezhi when talking about the rise of the Kidarites, because of the similarity of the Kidarites to the earlier Kushans. In fact, many conclusions about the origins of the Kidarites have been based on the Chinese historical sources which provide the above account of their rise, or the account understood to refer to their rise.

The Swat District is today part of the Pakistani province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Anciently, this area (basically the valley of the Swat river) was know as Uḍḍiyāna and was one of the “five kingdoms” north of Gandhāra that according to Faxian had been conquered by the “Yuezhi”.

Khodadad Rezakhani though thinks more prudent to consider the literary nature of the Chinese historical accounts and their tendency to follow patterns established by earlier historians and to repeat similar information. Here, we can identify cases of similarity between those accounts relating to the earlier Yuezhi (thus the Kushans) and the later Kidarites. As mentioned before, while talking about the Yuezhi and the Kushan, the

Shiji tells us that the Xiongnu attacked and drove the Yuezhi to the west. The

Hou Hanshu then provides information that the five

yabghus of the Yuezhi were eventually subdued by

Qiujiuque, the great prince of the

Guishuang. This is usually understood by modern scholars to mean that the ruler of the Kušān (the

Guishuang of the

Hou Hanshu) tribe or clan,

Vima Kadphises (i.e.

Qiujiuque), managed to assert his control over the other four clans or tribes of the Yuezhi people.

In turn, the

Wei Shu’s account of the rise of the Kidarites is remarkably similar to the composite account of these earlier sources on the rise of the Kushans, to the extent that the

Bei Shi also uses

Guishuang to refer to the tribe of

Jiduoluo (i.e.

Kidāra). The presence of five as the number of the countries “north” of Gandhāra conquered by him also exactly matches the description of the five

Yabghus of the Da Yuezhi as described in the

Hou Hanshu.

Following with Rezakhani’s

caveats, it is also worth noting that according to the

Wei Shu, the division of the Yuezhi to the

Da (Greater) and the

Xiao (Lesser) also holds for the Kidarites. While in the earlier account of the

Shiji, the

Xiao Yuezhi is a division of the tribe remaining behind in their homeland following the migration of the

Greater Yuezhi to the west, in the

Wei Shu account, they are simply those in the kingdom of

Jiduoluo’s son. This kingdom is said to be located in Gandhāra, with its capital at

Fulousha, or Puruṣapura (i.e. modern Peshawar). The conclusion from this could be simply that the later Chinese sources talking about the Kidarites should be taken not as merely “echoing” the earlier sources on the rise of the

Da Yuezhi and the Kushans, but also copying them wholesale, providing a narrative for the region which they simply knew as the territory of the Da Yuezhi and trying to fit in details such as the “five countries” and the “

Lesser Yuezhi” known from the earlier sources.

Rezakhani considers however that we can conclude that the Kidarites indeed ruled over the territory previously dominated by the

Da Yuezhi/Kushans, and that their embassies were received in the Chinese court as representing this territory. The Chinese even considered Balḵ to be the capital of the

Da Yuezhi, similar to the role of that city in the Kushan administration. Their path of invasion, as presented above, takes them across a certain range of mountains, identified differently by various scholars. In 1969 the Japanese scholar Kazuo Enoki proposed that the

Da Shan (Great Mountains) referred to in the

Wei Shu is the Hindu Kush and that

Bei Tianzhu is the Kabul-Jalalabad region or the classical

Paropanisadae.

Rezakhani’s view sums up quite well that of most Iranologists, but here we have a problem: like most Iranologists he does not know Chinese (and obviously, Early Middle Chinese even less) so that he only has access to translations, and to a limited pool of them (the only one I know about who is fluent in ancient Iranian languages and also in Chinese is De la Vaissière). The Japanese scholars Kazuo Enoki and Shoshin Kuwayama were the first ones to address the history of Central Asia and northwestern India from the analysis of Chinese sources. But in 2012 an important paper was published by the Chinese historian Xiang Wan criticizing their work in relation to their analysis of the Buddhist Chinese sources (meaning basically the accounts of Faxian and Song Yun). These are very tricky but also invaluable sources. On one side, they are almost exclusively interested in Buddhism, and ignore most secular aspects of the lands they crossed, but on the other side, theirs are the only eyewitness accounts of the Kidarite realm, written in the first person by a contemporary. There are simply no other sources comparable to them in this respect.

Wan’s paper is long and not an easy read (sixty-one pages with bibliography, and abundant philological and religious

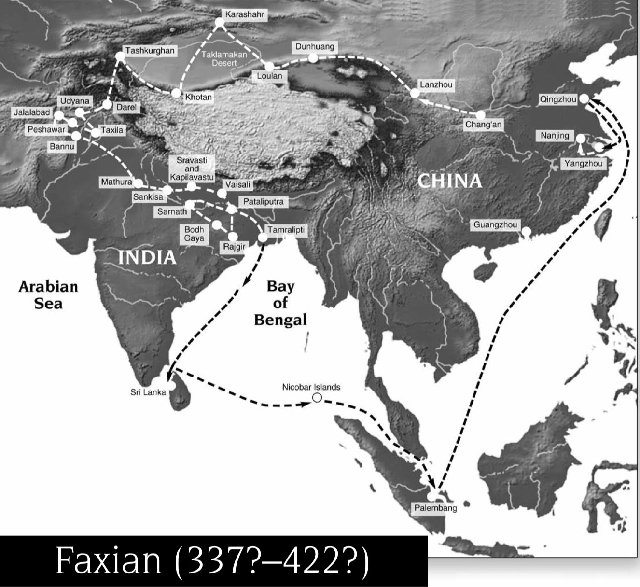

excursus about the meaning of Chinese words and Buddhist terms). Faxian’s voyage took place between 399 CE and 412 CE. He left Chang’an to look for Buddhist texts in India, and traveled by land through the Gansu corridor, passed through Dunhuang into the Tarim Basin, crossed the Pamir Range into Ferghana and proceed then into Sogdiana and Ṭoḵārestān, from where he crossed the Hindu Kush via the Kabul Basin and arrived to Gandhāra. He stayed in India for several years traveling extensively, and returned to China by sea, where he wrote down the account of his trip in 414 CE. He spent the next decade until his death translating the Buddhist texts he had brought with him from India into Chinese. This means he crossed all the Kidarite kingdom, from north to south, during the early reign of Yazdegerd I and when Chandragupta II ruled in the Gupta Empire in northern India.

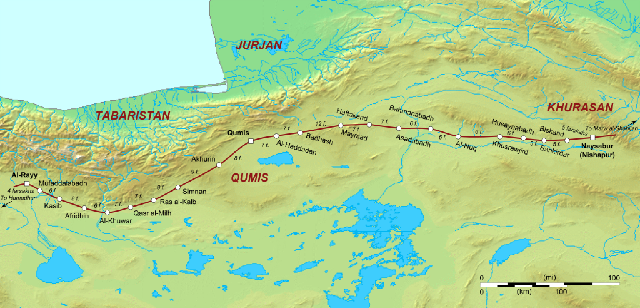

The travel of Faxian.

According to Wan’s analysis of Faxian’s account, together with the

Wei Shu and the

Bei Shi, Gandhāra itself (with Puruṣapura as its capital) was under direct Kidarite rule, with Kidāra himself having installed his own son as the ruler over the territory, while the “five kingdoms” to the north of Gandhāra were ruled by vassal kings. So, according to the Chinese accounts, Kidāra ruled north of the Hindu Kush over the

Da Yuezhi and his (unnamed) son ruled south of the Hindu Kush over Gandhāra and indirectly over some neighboring vassal kingdoms, and this (smaller) political entity was known to the Chinese as

Xiao Yuezhi. Despite the many parallelisms in the Chinese court chronicles between this story and that of the “authentic Yuezhi/Kušāns in the Hanshu and the Hou Hanshu, a pilgrim like Faxian did not need to follow courtly literary precedents, yet his narration follows roughly the same scheme, and makes perfect sense if we take into account that to the Chinese the terms

Kušān and

Yuezhi were completely equivalent, and the Kidarites identified themselves fully in their coinage and official documents with the Kušān heritage.

It is also clear from Faxian’s account that during his trip, Gandhāra was still a mainly Buddhist country, and its many Buddhist shrines and monasteries were still flourishing. From his account, it is quite clear that Kidāra himself either professed the Buddhist faith or acted like a benevolent patron towards its institutions (like the ancient Kušān kings had done). This is important, because Buddhist tradition attributes to “the Huns” (and specifically to the later king

Mihirakula) the demise of Buddhism in Gandhāra; but at least it seems clear that during Kidarite rule Buddhist still kept its preeminence. And archaeology confirms Faxian’s account, because there are no signs of destruction or abandonment in Buddhist monuments in Gandhāra attributable to the late IV or early V c. CE. This seems to be supported in a Chinese Buddhist manuscript from Dunhuang dated to 412-430 CE where it is described how a contemporary ruler and his army paid respects to the relics of the Buddha at

Uḍḍiyāna (the Swāt valley) and

Nagarāhara (Jalalabad in Afghanistan, where the ancient Buddhist complex of Haḍḍa stood). Given the geographical and chronological frame, this ruler can only have been the Kidarite ruler (probably not Kidāra himself, given the relatively late date), and this seems to be supported by the use of the Chinese title

Tianzi to refer to this ruler. The title means “Son of Heaven” (the title usually given to the Chinese emperor) but in its Sanskrit translation

Devaputra it was also a traditional title of Kušān kings.

The problem though is that Chinese Buddhist sources use exactly the opposite terminology than Chinese dynastic histories: in these sources, “Lesser Yuezhi” makes reference to Ṭoḵārestān and “Greater Yuezhi” to Gandhāra and Swāt. This particular use of the terminology in the Chinese Buddhist sources is explained by wan because understandably these sources were interested mainly in religious affairs, and it was in Gandhāra and Swāt where the most revered and larger number of relics of the Buddha were kept; some of them were kept at Balk, but that was nothing compared to what was hold south of the Hindu Kush. These Buddhist sources though (at least in Wan’s analysis) seem to be free from any need to follow slavishly the Hanshu or the Hou Hanshu in their descriptions. According to Wan, they use the name

Yuezhi like an ethnonym, to refer to the people (as in “political ethnic-tribal entity”), while they use the toponym

Jibin to refer to the country of Gandhāra, independently of who controlled it.

Another Chinese source that confirms the extent of Kidarite rule is the

Bei Shi, according to which a king called

Kidāra (which the Korean scholar Hyun Jin Kim considers more likely to be the attribution of the name of the dynasty to an individual king, rather than a personal name) conquered the territory north and south of the Hindu Kush some time before 410 CE and had subjected the Gandhāra region to his rule.

Let us leave aside now for a while the Chinese sources. How were the political arrangements in northwestern India, if (as we have seen before) an unknown authority/group/dynasty calling themselves

Alkhono in their coins seem to have been present too in Gandhāra at this time, how does that fit in with Kidarite rule? Some scholars, like the Dutch Indologist Hans T. Bakker, believe that the Alkhon Huns were a sort of confederation, in turn subordinated to the overall lordship of the Kidarite “Great Kušān King” north of the Hindu Kush. The main proof for this relationship is a silver bowl dated to the first half of the V c. CE found in Swāt to the north of Gandhāra. In it, four Hunnic riders can be seen hunting; one of them displays the elongated cranium that would be typical in Alkhon kings in later coinage, and two others wear crowns very similar to the ones that can be found in Kidarite coins and

bullae. This could be a hint at the Huns being ruled by four rulers in typical steppe custom (see my previous thread), one of whom at least seems to be clearly an Alkhon. Bakker also points out that when the Alkhons seem to have broken out with the Kidarites, they in turn seem to have adopted too this sort of government with four kings (one of whom would be the “supreme king”, as we will see).

Silver drahm issued by an anonymous Alkhon Hun ruler ca. 400-440 CE, imitating the coins of Šābuhr II. Notice the Alkhon tamgha on the obverse, to the left of the king’s bust.

Bakker and Wan disagree though in a key chronological point: the end of Kidarite rule in Gandhāra and the “independence” of the Alkhon Huns. According to Wan, after 420 CE the term

Yuezhi is not used anymore by Chinese Buddhist sources to refer to northwest India, and

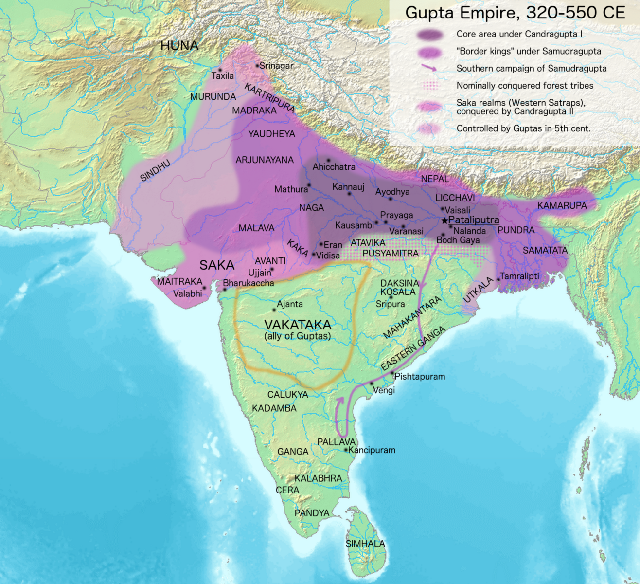

Jibin is used instead, and to him this denotes a shift in political suzerainty. But Bakker sets this shift twenty years later, to ca. 440 CE, when according to him the Kidarite Huns attacked the Gupta Empire during the last years of rule of Kumaragupta I, and it had to be his son and heir Skandagupta who defeated the invaders after these had reached almost central India. According to Bakker, this defeat would have marked the end of Kidarite rule south of the Hindu Kush, with the local Alkhon rulers becoming de facto independent in Gandhāra and Punjab.

The biographies of two latter Chinese Buddhist pilgrims, Sengbiao and Fasheng, are preserved in the

Mingseng Zhuan Chao, but this source does not document the visit of relics in Puruṣapura or Nagarāhara. Slightly before 439 CE when they arrived at Northwest India; the territory was being ravaged by war. Consequently, Sengbiao was hindered in Gandhāra, while Fasheng’s biography barely mentions his journey in Uḍḍiyāna (i.e. the Swāt Valley), where he visited the colossal statue of Maitreya.

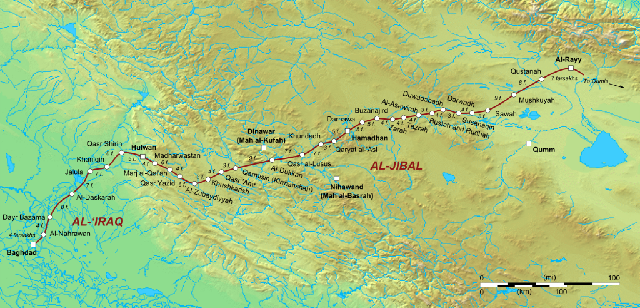

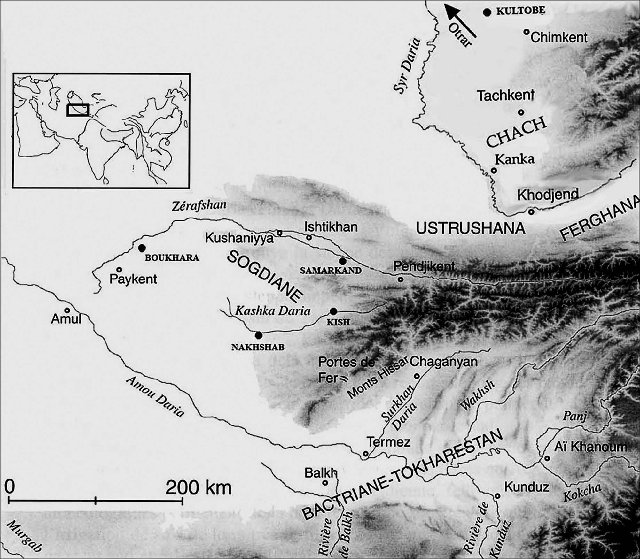

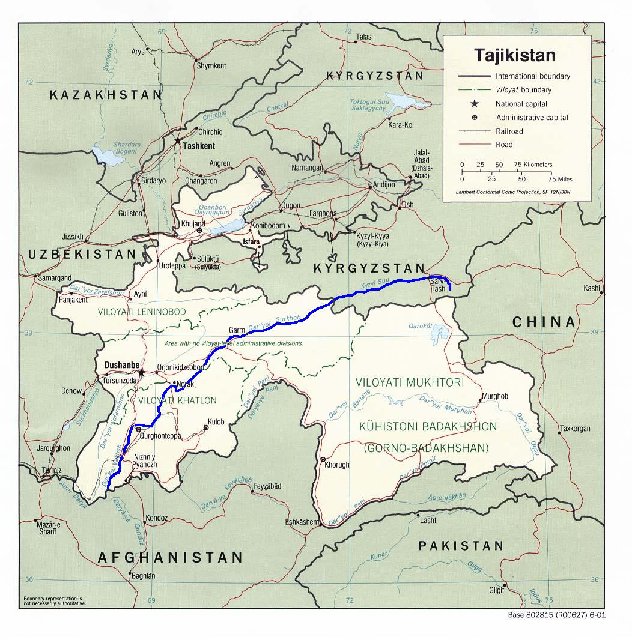

The situation in Ṭoḵārestān and Sogdiana, which were also under Kidarite rule, was studied by French historians Frantz Grenet and Étienne de la Vaissière in the 2000s. According to Grenet, Chinese documents seem to suggest that regular contacts with China were interrupted between ca. 313 and 437 CE, which must have had a disastrous effect on the merchants of the Sogdian and Bactrian cities. In consequence, the Sogdiana that was invaded by the Huns was a stagnant country, and the Hunnic invasion seems to have had a dynamizing effect on it. According to Grenet, archaeological data show that from the V c. CE onwards, Sogdiana entered a dynamic phase that would last until the Arab conquest in the VIII c. CE.

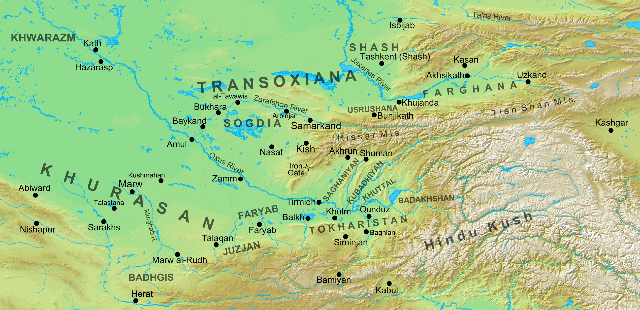

Map of Sogdiana and northern Ṭoḵārestān. The Hissar Mountains divided Ṭoḵārestān from Sogdiana, and the Iron Gates were the main pass between both regions.

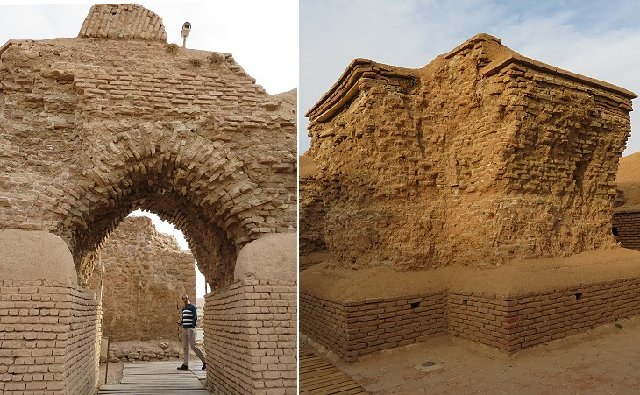

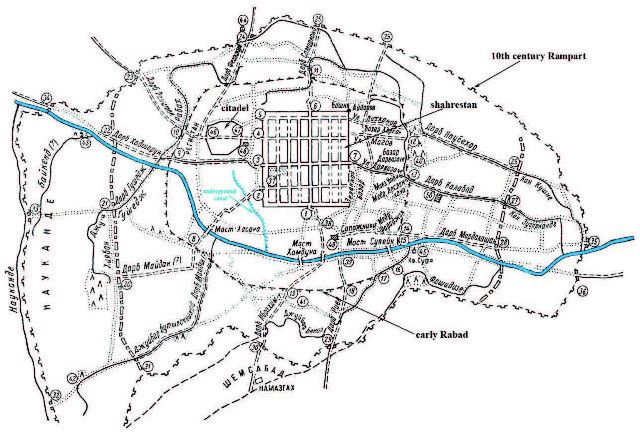

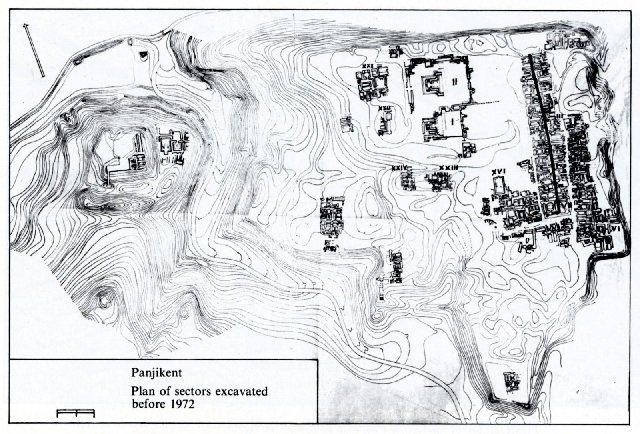

It was under Kidarite rule that three of the more famous Sogdian cities were founded or re-founded (see Chapter 7.8 of my previous thread: Boḵārā, Panjikant and Paykand. The latter, built to the south of Boḵārā, midway between this city and the crossing on the Āmu Daryā at Āmul, was probably built to act as the Kidarite/Sogdian counterpoint to the great Sasanian fortress of Merv, which was located 200 km to the southwest of Āmul. This was proposed in 1989 by the Soviet archaeologist G.L. Semenov and seems to have been largely accepted today. The Soviet archaeologist Aleksandr Naymark and the Russian archaeologist Andrey V. Omel’chenko, who directed excavations at Paykand for thirty years, even consider that a first phase in the reconstruction of Paykand as a great-scale military base could have happened in the late III or early IV c. CE, under Kushano-Sasanian control, and that when the Huns took the city, they enlarged it and the citadel even more. Paykand is mentioned by many medieval Islamic authors, who reported that Paykand was older than Boḵārā and that it was well fortified; this last feature earned the city its nickname, “Brazen city” (

shārestān-e rūīn). Interestingly, Ferdowsī mentions a “Brazen castle” (

rūīn-dezh or

dez-e rūīn) in his

Šāh-nāma in connection with the third campaign of the Iranian prince Esfandīār against the Turanians. Already the German scholar Josef Marquart in the first third of the XX c. identified this castle with Paykand.

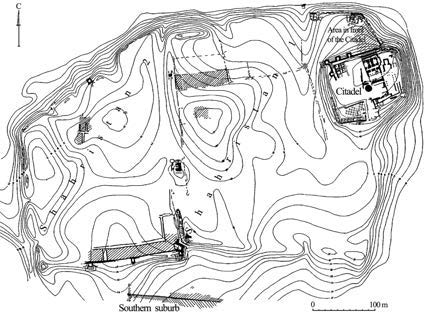

Other than the stratigraphy and the archaeological dating, Semenov observed that the primitive plan of the three cities, dated to the first half of the V c. CE, presents important similarities:

- The city walls followed a rectangular outline.

- The streets were laid following an orthogonal ground plan.

- The citadel was built physically separated from the city walls, overbuilding an older settlement.

Linguistic research has also showed that the very name Boḵārā could also be derived from the foundation (or re-foundation) of the city at this time (Chinese sources of the early V c. CE support this, as according to them, Boḵārā would’ve have been the capital of a kingdom of the lower Zarafšān valley). In the early XX c. the German scholar Josef Marquart proposed that “Boḵārā” could derive from the Sogdian form for “the new residence”, while in the second half of the XX c. the American Iranologist R. N. Frye proposed a similar etymology derived from the Sogdian for “the new town”. These “new towns” are of a smaller size than the large fortified precincts from the Hellenistic era, and thus more aligned with the reality of the shrunk Sogdian cities of the late IV and early V c. CE: 15-20 ha. for Boḵārā, 8 ha. at Panjikant and Paykand and the remains at Erkurgan (ancient

Naḵšab) near Samarkand, which even now remained the second largest Sogdian city with 70 ha (more about this below); the archaeological Franco-Uzbek mission in which Grenet took part confirmed that the foundations of the ramparts of late ancient Samarkand are dated to the early V c. CE. It is quite possible that the (now destroyed) city of Rabinjan, between Boḵārā and Samarkand, was also founded at this time, and that the same happened at Kurgan Tepe and Durmen Tepe, located slightly to the west of Samarkand.

Map of medieval Boḵārā (maximum extension in the X c. CE under the Samanids), showing the Hippodamian city re-founded under Kidarite rule in the V c. CE with a separate citadel, according to Soviet archaeologists.

That these cities underwent through a period of prosperity during the V c. CE is attested by the fact that Samarkand, Paykand, Panjikant and Boḵārā had to rebuild and enlarge their walled precincts before the century ended. All these foundations seem to have been done during a limited temporal horizon, and in a systematic and deliberate way by a single authority, following roughly similar plans in most places. In the case of Samarkand, it also implied the phenomenal effort of raising the level of the floor of the old citadel. Rectangular cities with Hippodamian city plans were unknown in Central Asia in old Hellenistic settlements; the closest known example would be Taxila in the Punjab. Grenet thinks that the inspiration for these foundations should be sought in Sasanian royal foundations in the East like Herāt, a city with a square plan and which in an old British plan from 1842 the orthogonal traces of its foundations can still clearly be seen.

Grenet also speculates that the lower city of Balḵ could have reached its largest extension during Kushano-Sasanian times (its walls enclosed a surface of 400 ha., making it by far the largest city in Central Asia at this time) and that its internal layout could have also have followed an Hippodamian plan, making it an example to follow in the Sogdian foundations. The walled precincts of the Sogdian cities never reached the monumental size of those of Balḵ and Merv, which were probably far too oversized for their population levels in Late Antiquity (we know from the account of the Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang in the VII c. CE that this was certainly the case for Balḵ). Two IV c. CE fortresses near Samarkand, at Kindikli and Dzhartepe, were turned in the early V c. CE respectively into a country manor and a monumental temple (both without defensive fortifications) which suggests a peaceful and prosperous environment. Archaeology shows a strange paradox for Sogdiana during the V-VII c. CE: during this time, the Sogdian lands were part of empires who were enemies of

Ērānšahr (successively, Kidarites. Hephthalites and Türks), but Sasanian influence increased over time during these centuries, substituting the Hellenistic-Kušān legacy of Antiquity. In 313 CE, Sogdian merchants in China still made their accounts in silver staters, but in 639 CE they used Sasanian drahms (explicitly described as such).

The change in money coinage happens precisely at this time when the Sogdian cities began issuing copies of the Sasanian drahms of Warahrān V and Yazdegerd II (and kept issuing them until the Arab conquest). The local coinage of Ṭoḵārestān would survive a bit longer, and it would not be substituted for local copies of Sasanian coins until the 470s and 480s. Among the Sasanian influences, Grenet notes also religious ones. The Sogdian religion continued to be a traditional Iranian religion, without the many changes introduced in it by the Sasanian mowbeds in Iran proper since the III c. CE (Khodadad Rezakhani even uses the word

Zoroastrianism to refer to this “reformed” form of the religion and

Mazdeism to refer to the original form that was still practiced outside the borders of

Ērānšahr, although I don’t know if this usage is followed by any other historians). The Kidarite control of both sides of the Hindu Kush and Sogdiana, together with the increased dynamism of the Sogdian cities, introduced Indian iconography in Sogdian religion, but it remained an Iranian religion (in a paper, Grenet described it as “Iranian deities in Hindu garb”). But curiously, Buddhism made no inroads in Sogdiana. Not a single Buddhist shrine or monument has been found there, and this is confirmed by the accounts of Chinese Buddhist pilgrims, who reported about the indifference or even hostility of Sogdians towards Buddhism. The Sasanian influence in Sogdian religion, according to Grenet, was the popularization of burials according to the Zoroastrian rite (exposition of the corpses to carrion-eating beasts and later the inhumation of the bones in ossuaries) while previously corpses were disposed of by inhumation. Grenet thinks (through the study of the forms and iconography of the ossuaries) that this custom became extended in Sogdiana from the Sasanian Empire rather than from Khwārazm, where it had also been a common practice before. Grenet also pushes forward the hypothesis (for which he admits he has no evidence) that perhaps the Sasanians engaged in some sort of “missionary activity” in Sogdiana, similar in its objectives to those stated by the

mowbed Kirdēr in his III c. CE inscriptions (but obviously with much more peaceful methods), as for example across these centuries the ossuaries in Sogdiana show a constant trend towards aligning themselves with the ritual prescriptions of the

Vendīdād. There is also the information that reached the Tang court in China in the VII-VIII c. CE that:

Jiu Tangshu, 198, 24b:

(…) the diverse Hu peoples of the western countries (i.e. the peoples of Central Asia, the Sogdians in particular) who follow the worship of the Heavenly God have all of them learnt this religion by going to learn it at Anxi (i.e. Iran).

Grenet also makes an interesting proposal regarding the financing of such a huge wave of large-scale construction: that it was financed by the tribute received from the Sasanians, especially under Hephthalite rule at the end of the V c. CE, but possibly also during Kidarite rule. As we will see when we deal with the reign of Yazdegerd II, he entered war against the Kidarites because he refused to keep paying the tribute that “his ancestors” had paid them, and that can only mean Yazdegerd I and Warahrān V (at least during part of his reign). Grenet supports the hypothesis that military contingents from the Sogdian cities joined the Kidarite and Hephthalite armies in their raids against eastern

Ērānšahr, and that this would have been a direct way to explain the growing influence of Sasanian culture in Sogdiana (city-planning, funerary customs, etc.) as well as a way to acquire direct wealth through looting. Sasanian captives may have played an important role as well.

Map of the excavations at Paykand. It was built on an existing hill, with the V c. CE reconstruction re-using the ancient foundation as the citadel while a new šahrestān on a Hippodamian plan was built at a certain distance from it (like at Boḵārā), of which you cans see a corner of the walls on the lower left side of the map.

I agree with Grenet in this respect, because forcing conquered peoples into the armies was the normal practice among both the Xiongnu and the European Huns, so there’s no reason why it should not have been the case with the Central Asian Huns. And as Grenet points out, this hypothesis has the support of the Zoroastrian apocalyptic text

Zand-ī Bahman Yašt, where “the Sogdians” are listed among the invaders of Iran at the end of Zoroaster’s millennium. And the same would have been true in the cases of Ṭoḵārestān and Gandhāra too, obviously.

The main commercial route between Central Asia via Balḵ and Kabul could have been interrupted due to the state of war in Ṭoḵārestān, and the alternative route further to the east developed by Indian and Sogdian traders since the III c. CE seems to have gained importance. This was a much longer route that implied traveling 1,100 from Samarkand to Khotan crossing the Pamir Plateau and roughly 400 km from there crossing the Karakorum range into the upper Indus valley. This route is longer and riskier than the main one through Balḵ, Bāmīān and Kabul to Gandhāra, so its rise to prominence must have been due to major reasons that prevented its use. The crossing of the Karakoram range was particularly dangerous and involved travelling along narrow paths carved on the side of mountain cliffs and on hanging bridges across precipitous valleys. The French scholar Étienne de la Vaissière linked its appearance to the Sasanian conquest of Ṭoḵārestān in the III c. CE, when this region and the Hindu Kush passes were first affected by war.

During the construction of the Karakorum Highway between Pakistan and China, a great number of inscriptions were found dated to the III-V c. CE and which were carved by merchants that followed this route, in the Pakistani region of Gilgit-Baltistan. They are located at several places, of which the most interesting in our case is Shatial, where hundreds of inscriptions have been found, with those in Sogdian being the most abundant ones:

- 550 in Sogdian.

- 410 in Brāhmī.

- 12-15 in Kharoṣṭhī.

- 9 in Bactrian.

- 2 in Parthian.

- 2 in Middle Persian.

Apart from these ones, only 3 more Bactrian inscriptions have been found, for a grand total of more than 650 inscriptions in Sogdian in all the locations. Clearly, this trade route was more frequented by Sogdian than by Bactrian merchants. At campsite there are also inscriptions in Hebrew, and near Shatial, some interesting inscriptions in Chinese have been found. Most of the Sogdian inscriptions are merely onomastic statements: “X. son of Y” or “X, son of Y, son oz Z”, etc. The longest one reads:

I, Nanai-Vandak, the (son of) Narisaf, came on (here) the tenth and have requested the favor from the soul of the holy place K’rt (that) I reach Tashkurgan quickly and see (my) dear brother in good (health).

Some Sogdian names appear also in the inscriptions in Brāhmī script. But what De la Vaissière found more interesting from the Sogdian inscriptions (mainly in Shatial, but also at two other sites) is that the first or last name more frequent in them is

xwn (Sogdian rendition of

Hun). He also noticed a peculiar pattern:

xwn is always displayed always as part of the son’s name, but never as part of the father’s name: it is always “

xwn son of X”, but never “X son of

xwn” with “X” being a purely Sogdian name. These onomastics are only explainable if we assume that the inscriptions to a period not long after the Hunnic conquest of Sogdiana, when a first generation of Sogdians were starting to assimilate and to display a “Hunnic” identity. De la Vaissière dated the inscriptions to the late 430s or early 440s CE at the very earliest because some of these Sogdian individuals appear associated to the Sogdian city of Māymorḡ, which is first attested anywhere in an entry dated to 437 CE in the

Wei Shu. The fact that there are no names with “

xwn” quoted as fathers probably means that the end of Sogdian trade along this route must have happened in quite a brusque way, before a second generation of “Hunnic Sogdians” had time to appear. In contrast, the Brāhmī inscriptions seem to date mainly to the III-IV c. CE.

Some of the rock inscriptions at Shatial.

According to De la Vaissière, archaeology shows that great agricultural progress was made in Sogdiana during the V-VI c. CE, which allowed for a surge in population. South of Samarkand, three quarters of archaeological sites are dated to this period and most of them were abandoned afterwards. Of 131 settlements at the Zarafšān Steppe and between the Zarafšān River and the Dargom canal, 115 appear during this period, while at the end of the Middle Ages only 52 remain. Also, it is during this period when in the swampy part of the Zarafšān valley region of Ištiḵan, 100 km west of Samarkand is developed and drained. The same situation has been observed at the Karši Oasis (where Erkurgan, ancient Naḵšab, is located): of 460 sites of all periods, 350 were occupied between the V-VI c. CE. The western limit of the Boḵārā Oasis, which had been retreating in front of the Kyzyl Kum Desert for centuries, stopped its retreat and advanced 22 km westwards thanks to the extension of the irrigation system at the expense of the sands of the desert. De la Vaissière also dated to this period the construction of great works like canals, irrigation systems and walls around the oasis, to protect them both from encroachment by the desert and nomadic raids. According to the American historian R. N. Frye, it was during this period that the 250 km long wall around the Boḵārā Oasis was built. The IV-VI c. CE were also the heyday of Naḵšab, which with a surface of 150 ha was by far the largest Sogdian city (Samarkand at this time had an extension of only 70 ha within its walls).

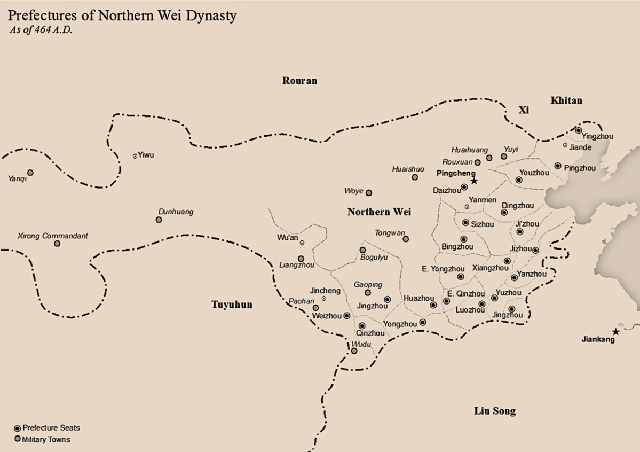

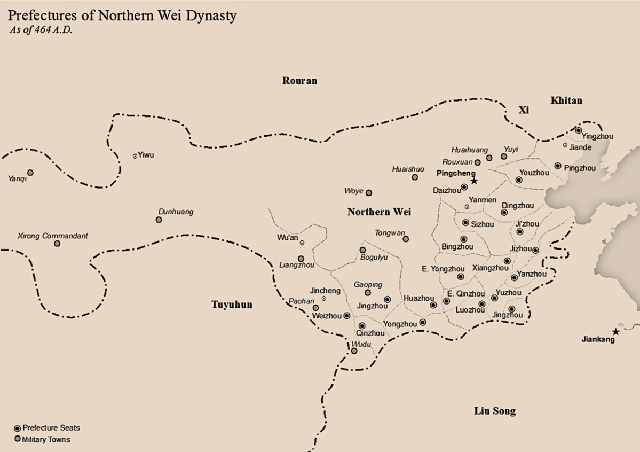

Territories ruled by the Northern Wei in northern China in the V c. CE. This dynasty was of nomadic origins, as they were descended from the Tuoba clan of the Xianbei people who conquered the North China Plain after the fall of the Eastern Han.

De la Vaissière thinks that the three four decades of the V c. CE would have been a peaceful time in Sogdiana which would’ve allowed the peaceful integration of the refugees from the Syr Daryā valley into Sogdian society, and also the start of the assimilation of the Sogdian population with the new Hunnic political order, although in this respect it’s important to note that both he and Grenet are defenders of a late date for the rise of the Kidarite kingdom, which they date to the 430s CE, a date which is contested by numismatists and some historians (like K. Rezakhani or Xiang Wan) and which seems to have been discredited by the most recent scholarship. In my opinion, the economic progress and the demographic growth in Sogdiana can be dated to this time safely independently of which date is chosen for the rise of Kidāra. The main argument for the “late date” of Kidara’s reign defended by De la Vaissière, Grenet or Kazuo Enoki is this fragment of the Wei Shu, dated to 457 CE, when an embassy from Sogdiana reached the court of Emperor Wencheng of the Northern Wei and informed the Chinese about the latest developments in Samarkand, where a king named

Huni was ruling:

Wei Shu,102:

The country of Sute is located west of the Pamirs. It was called “Yancai” in ancient times. It is also called “Wennasha”. It is located next to a great swamp and to the north-west of Kangju. It lies 16,000 li from Dai (the capital of the Western Wei). Anciently, the Xiongnu killed the king and seized the country. King Huni is the third one of his line to rule.

According to this theory, Kidāra would have been a Hunnic ruler who rose in Ṭoḵārestān in the 420 CE. After seizing control of this country, he tried to attack the Sasanian empire and after being repelled by Warahrān V, he then turned to the north and south and seized Gandhāra and Sogdiana in the 430s CE. The problem with this chronology is that while it seems to align well with the Wei Shu, it goes against the numismatic evidence and, the interpretation of Faxian’s testimony by Xiang Wan and possibly also the Armenian chronicler P’avstos Buzand, who wrote that Šābuhr II had been defeated twice between 368 CE and 374 CE by the “King of the Kušān” (the only Hunnic kings who called themselves such were the Kidarites). Priscus of Panion is of little help here, as his account of the “Huns called Kidarites” is posterior to the one in the

Wei Shu.

This theory though would allow perhaps for a better explanation of the decline of Ṭoḵārestān (see below). According to it, a new Hunnic clan/dynasty, the Hephthalites, would have risen in Bactria against the Kidarites relatively early, so that this region would have been contested from the 440s until the 470s between them, the Kidarites and the Sasanian

Šahān Šāhs Yazdegerd II and Pērōz, which would explain the devastation suffered by it. There are also problems with this chronology in its later phases though: according to western sources (Priscus mainly) the Sasanian king Pērōz seized Balḵ from Hunnic foes who were not Hephthalites (who were his allies in that war). That leaves only the Kidarites as the ones controlling Balḵ as late as 474 CE. On the other side, between 456 CE and 509 CE several Sogdian embassies reached the Chinese court, but none of them identified as “Hephthalite” before the one in 509 CE, which means that at least until 509 CE the Hephthalites did not control Sogdiana.

In contrast to the continuity that can be detected in Gandhāra and the newfound dynamism of Sogdiana, the V c. CE is a time of economic shrinkage and populational loss in Bactria/Ṭoḵārestān. The invasions of the IV c. CE seem to have had a quite different character on both sides of the Amu Darya. In Sogdiana, the archaeological record shows no signs of fire or violent destructions but detects a sudden presence of ceramics characteristic of the Džetyasar culture from the middle and lower Syr Darya. In the original homeland of this culture, considerable destruction can be observed at this time has been detected by archaeologists, together with mass depopulation. The interpretation given to these facts by scholars (see the previous thread for more detailed information) is that waves of refugees fled south and settled in Sogdiana, where the local Sogdians seem to have submitted to the northern conquerors (the Huns in all probability) without resistance, thus sparing most of the destruction.

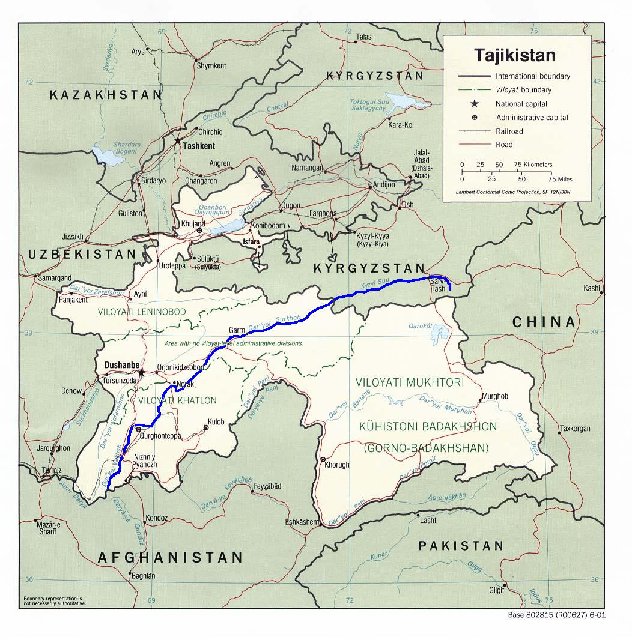

The Vakhsh River in what’s today Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan.

The archaeological horizon is completely different for Ṭoḵārestān though, starting with the IV c. CE. A shrinkage or even vanishing of the urban centers in the plains and valleys of northern Ṭoḵārestān has been detected in all archaeological digs. In the Vakhsh valley north of the Āmu Daryā (modern Tajikistan) the irrigation system was partially abandoned, while south of the Āmu Daryā, layers of fires have been found in most sites in the Kunduz region. Up to the Türk period, the Bactrian valleys north of the Āmu Daryā seem to have been scarcely inhabited. When the Chinese monk Xuanzang visited Balk in the 630s, he noted that although the oasis was agriculturally very rich, the city itself was scarcely populated within its huge circuit of walls, and that despite having more than 3,000 Buddhist monks in 10 convents, most of them were poorly informed about the Buddhist doctrine, due to frequents sieges and lootings suffered by the city (including the prestigious Nowbahār monastery). Ṭoḵārestān does not seem to have recovered until after the Arab conquest, and the same seems to be true for its capital Balḵ.

There are also traces in Sogdian art of Bactrian influence; historians think that it is possible that there was a migration of artists northwards to Sogdiana as a result, carrying with themselves the Indian influences that had been commonplace in Bactrian art since the I c. CE. For example, the first paintings at Panjikant are almost identical in style to the last paintings at Dal’verzin in Ṭoḵārestān. De la Vaissière also notes the appearance of Bactrian toponyms in Sogdiana (like Kušāni/Kušāniyya) which according to this historian can only be due to migrants/refugees who resettled in Sogdiana from their southern homeland.

Map of Panjikant, as excavated in 1972. The citadel was established on upper ground to the left of the map, separated from the original šahrestān, built on a Hippodamian plan located to the right of the map. As in other Sogdian cities, the city grew in the VI, VII and early VIII c. CE and the original Hippodamian plan became blurred.