4.14 THE END OF THE KIDARITE KINGDOM.

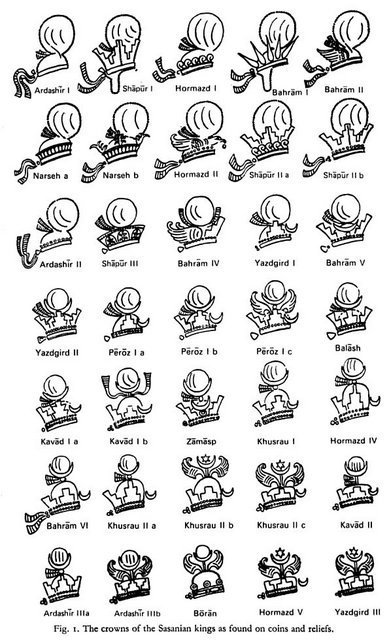

The succession war recorded in practically all the accounts between Pērōz and his brother and the lack of coins minted in Hormazd III’s name has raised some doubt. So, some historians think that Pērōz would have been appointed king by his father and that it would have been Hormazd III who revolted against him, based on the lack of coins minted in the latter’s name and because Łazar P’arpec’i attributed 27 years of reign to Pērōz, which would only make sense if he counted from 457 CE. This could be further supported because, as showed by the numismatist Nikolaus Schindel, Pērōz displayed a different crown on his coinage from his second regnal year onwards. But according to Daniel T. Potts and Nicholas Sims-Williams, there are three

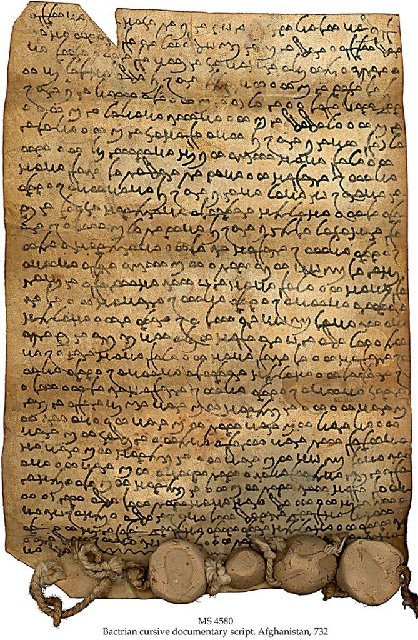

Bactrian Documents dated to these confused time frame that could shed some light on the issue. In these documents, a certain

Kirdēr-Warahrān appears with different titles. In one of them, he bears the title “loyal to Pērōz” and on the other two is called

*Hormazd-farrox (“famous in Hormazd’s name”). To these scholars this seems to show that there was indeed a civil war between Pērōz and Hormazd, and that this Kirdēr-Warahrān allied first with one brother and then with the other, and that he accordingly received honors from each of them.

Then there is the issue of Pērōz’s flight to Hephthalite territory, and asking for their help, among them Shapur Shahbazi and Rahim Shayegan (also earlier historians like Theodor Nöldeke, Josef Marquart or Arthur Christensen); in the post about Pērōz’s accession to the throne I followed their theory. But not everybody agrees with that. Shayegan and Shahbazi base their refusal of Pērōz’s flight to Hephthalite territory on the Armenian sources, in which this story is completely absent. And this is important, because these sources are the ones closest in time to the events (they were written in the second half of the V c. CE or slightly later), and they were written within the Sasanian Empire.

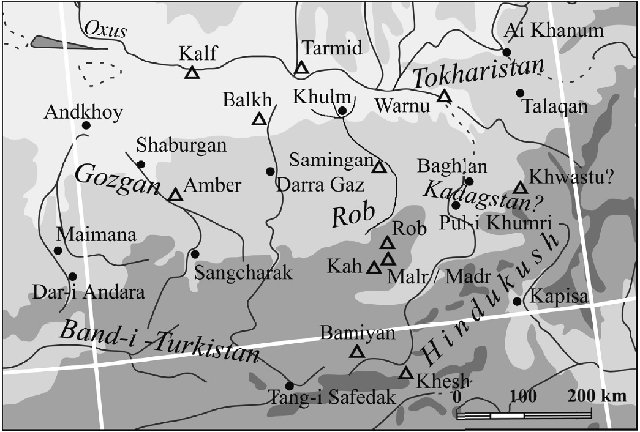

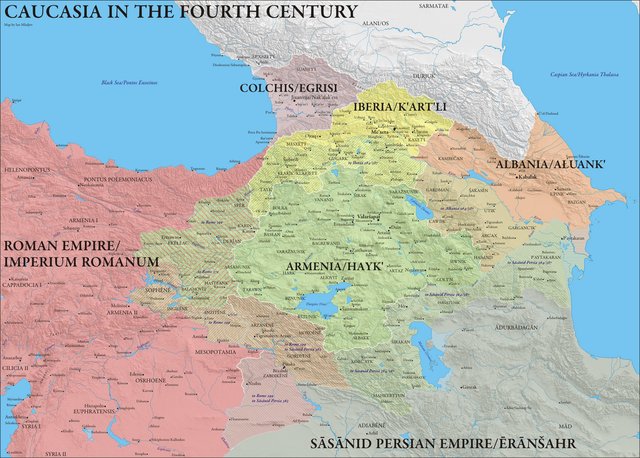

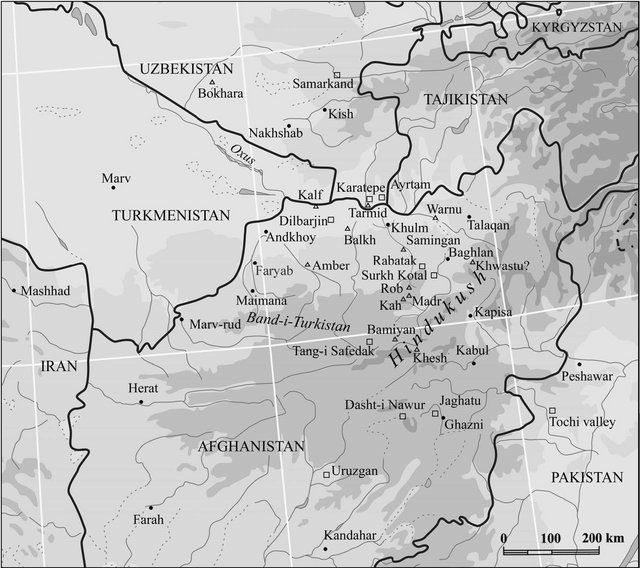

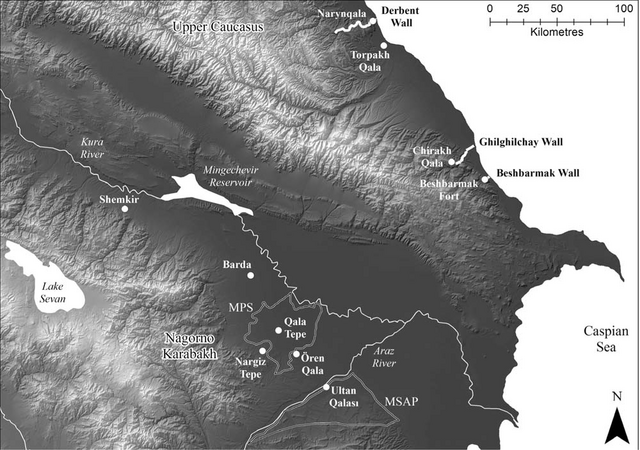

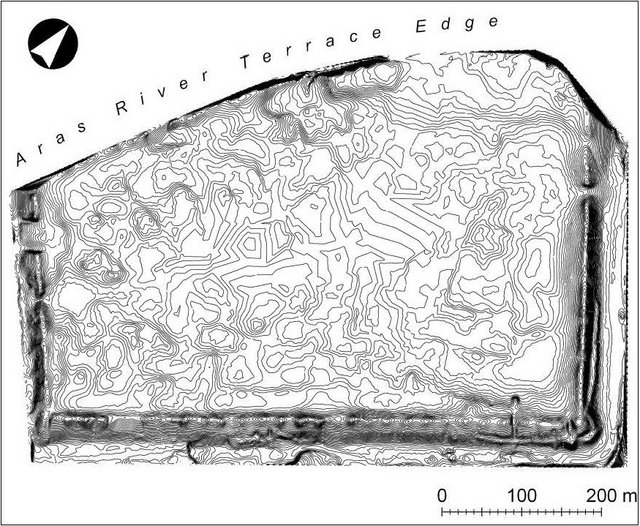

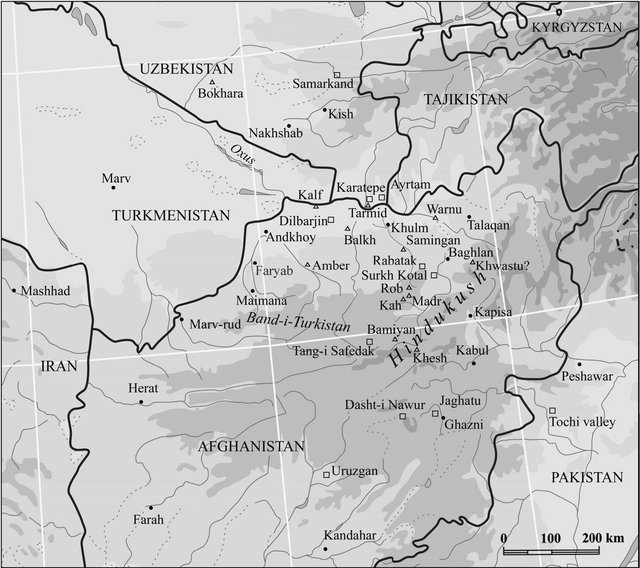

Although I have already posted this map in previous posts, I will post it here again as this post will contain again plenty of geographical terms, especially in Ṭoḵārestān. The “Saghaniyan” in the map is the “Čaḡānīān” in the text.

But not everyone agrees with it, seeing that almost all the Perso-Arabic sources agree on this point. It’s worth noticing that Pērōz would not have been asking for help the same people who had defeated his father a few years earlier (the Kidarites) but to the Hephthalites, who presumably would have rebelled against them, in a tactic similar to the alliance of Xusrō I in the VI c. CE when he allied himself with the Türks against the Hephthalites. Not only Ṭabarī, but also Bal’amī and other sources wrote that Pērōz was

Sakān Šāh when his father died, and Bal’amī specifies that he was in Sīstān when his father died. The key issue here is where do the Perso-Arabic sources locate the Hephthalites at this point in time, as modern historians place them in eastern Ṭoḵārestān, as we have already seen.

Perso-Arabian sources differ considerably when placing the Hephthalites at this point in time:

- Ṭabarī: “Khorasan” and “Ṭoḵārestān”.

- Nihāyat al-arab: Kābul or Kābolestān.

- Dīnawarī: Kābul/Kābolestān, Čaḡānīān and Balḵ.

- Ferdowsī: Čaḡānīān.

- Bal’amī: Ṭoḵārestān, Balk, Badaḵšān and Ġarğestān.

As you can see, Ṭabarī is the only source who mentions “Khorasan”. In late Sasanian times, “Khorasan” designated one of the four large partitions in which Xusrō I divided his empire, and which encompassed Abaršahr (ancient Parthia), Gorgān, and the territories reconquered by him in Ṭoḵārestān and the Hindu Kush. In Islamic terms though the term came to encompass practically all of the Islamic East north of India, including all of Transoxiana. So, his account is the only that could have accounted for the use of troops recruited within the Sasanian borders. Bal’amī locates the Hephthalites in Ṭoḵārestān at large (as does Ṭabarī), without specifying further, while Dīnawarī limited Hephthalite control to the Bactrian region of Čaḡānīān, which is also quoted by Ferdowsi under the name of

Čaġān. The region of

Čaḡānīān is located to the northeast of Termeḏ, in the upper valley of the Sorḵān Daryā River, and it formed the northeastern border of Ṭoḵārestān. According to Dīnawarī, the Hephthalite lands limited with Balḵ, but according to Bal’amī, Balḵ was already controlled by them.

Badaḵšān is located between the upper valley of the Āmu Daryā and the Hindu Kush. The

Nihāyat al-arab is the only source that specifies the alleged destiny of Pērōz when he fled the Sasanian Empire to request for Hephthalite help: Kābul, and Dīnawarī also says that Kābolestān was under Hephthalite control.

Ġarğestān is a region located on the upper valley of the Morġāb River, to the east of Herāt.

So, if we accept the accounts in the Perso-Arabic tradition as veridic ones, in 457 CE the Hephthalites would have already in control of most of Ṭoḵārestān, would have already been in control of the Bactrian territories north of the Amu Darya, and would control the main pass across the Hindu Kush to India, the Kābul basin (Kābolestān). They would have probably cut Kidarite-ruled territory in half. The Kidarites retained control in Gandhāra for some more time, and in Kashmir even longer, as the

Beishi records an embassy from

Jiduoluo (the Chinese term for

Kidarite) coming from Kashmir in 477 CE, and until 509 CE Sogdiana kept sending its own embassies to China, which the Chinese sources named differently from the ones sent by the

Yeda/

Hua. In this respect, it’s important to keep in mind that the first Hephthalite embassy to China is recorded by the

Weishu/

Tongdian in 456 CE, just a year before the death of Yazdegerd II and the start of the succession war between is two sons, so chronologically it is perfectly possible that the Hephthalites had already formed an independent state by then, able to send its own embassies to the court of the Northern Wei. There is absolutely no historical account or proof in which to base this assumption, but I agree with Hans T. Bakker that this sudden appearance of the Hephthalites as independent players north of the Hindu Kush must have been related to the Hunnic defeats in northwestern India and probably also to the long war between Kidarites and Sasanians, in which the former had also suffered defeats against Warahrān V and Yazdegerd II.

Again, I have already posted this map, but I am posting it again. It completes the map above for a proper following of most of the toponyms in the text. Notice the location of Termeḏ (“Tarmid” in the map) and Tālaqān to the east of Ṭoḵārestān.

Another important point is the prize that Pērōz had to pay the Hephthalites in return for their alleged support against his brother Hormazd III. According to Ṭabarī, Bal’amī and the

Nihāyat al-arab, he had to hand down the city of (

al-)

Tālaqān to the Hephthalites, but the identification of this city is problematic, as there are several cities called so in Greater Khorasan. The

Tālaqān located near Qazvin can be completely discarded as it is located in the northwest of Iran, the are two other candidates:

- A city now disappeared that was called Tālaqān and that according to Islamic geographers was located in Gūzgān, between Balḵ and Marw-Rūd and probably near Maymanah, in northeastern Afghanistan.

- The Nihāyat al-arab names specifically the city of Tālaqān in northern Ṭoḵārestān, between Balk and Kondūz.

Both candidates are located south of the Āmu Daryā, which would agree with the general consensus among historians that at this time the limits of the Sasanian Empire did not extend north of said river. Dīnawarī and Ferdowsī though wrote that the price paid by Pērōz was the city of Termeḏ, also in Ṭoḵārestān but on the northern shore of the river, in its confluence with the Sorḵān Daryā. And Ferdowsī adds the city of

Vīsehgerd to the price paid, which was located north of the Āmu Daryā. The geographical problems don’t stop here, though: all these cities are located east of Balḵ, which would mean that after his long wars, even after his defeat in 453 CE, Yazdegerd II had managed to recover Balḵ and most of Ṭoḵārestān, which is hard to understand given that this seems to contradict one of the surviving fragments left by Priscus of Panion (if the city of

Balaam that according to him was the Kidarite capital and was conquered by Pērōz is indeed the same as Balḵ).

The name of the Hephthalite king is also problematic. Most sources do not name him, but he is named as

Faġānīš by Ferdowsī and as

Ḵušnawār/Ḵušnawāz by Bal’amī (

Xašnawāz in MP). According to the French scholar Xavier Tremblay, the New Persian

Faġānīš is a corruption of the Sogdian word for “husband”. The last Hephthalite king according to Ferdowsi also had this same name, and the first

Faġānīš would have been succeeded by the

Ḵušnawār/Ḵušnawāz of Bal’amī’s account. Ṭabarī and Dīnawarī name a certain

Aḵšonvār as the Hephthalite king that would later inflict three devastating defeats upon Pērōz; it is unclear if it is the same name, corrupted by textual transmission. In its second form

Aḵšonvār, it is probably an Arabic corruption of the Sogdian word for “king” (literally “he who holds power”) and some scholars think that it may have been a title displayed by all the Hephthalite kings. The real problem though is that neither of these names is attested in sources other than literary ones. Hephthalite coins do not display the king’s name, only his effigy and the letters ηβο (

ebo, abbreviation for Bactrian

ηβοδαλο,

ebodalo), or the Hephthalite

tamgha.

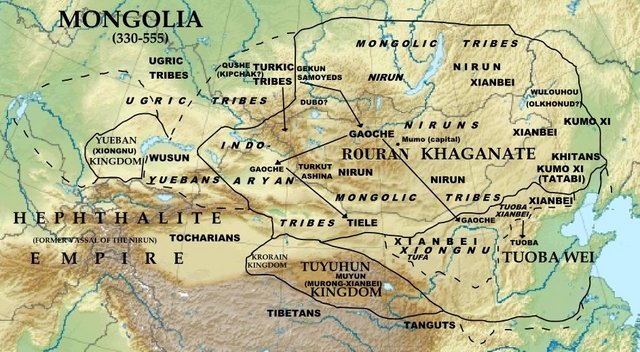

As described by the Austrian numismatists Michael Alram and Matthias Pfisterer, the Hephthalite

tamgha has curious origins. It appears for the first time in Alkhan coins from Kābolestān in the late IV c. CE, but then it disappears and appears only in a coin by the Alkhan king

Khiṅgila minted in Gandhāra. Nevertheless, during the first half of the V c. CE appear in Ṭoḵārestān some coins minted in name of a certain king

Tobazini that imitate Sasanian coins of Warahrān IV. The numismatist Nicholas Sims-Williams believes that

Tobazini could be a composite from the Turkic

Tupa or Chinese

Dubo, which was a Turkic tribe ruled by the Rouran. Sims-Williams proposed that maybe this king spent some time with the

Tupa tribe, and hence his name “under the protection of the

Tupa”. What is remarkable about these coins is that they display the Hephthalite

tamgha, and from this moment in time onwards, this

tamgha comes to be associated exclusively with the Hephthalites not only in coins but also in seals and other objects, in Ṭoḵārestān and in Sogdiana. The common use of the Hephthalite

tamgha by both Hephthalites and Alkhan has been interpreted by Alram and Pfisterer (cautiously) as a hint at a common origin of both dynasties/clans.

Obverse of one of the coins issued by “Tobazini”. To the right, Hephthalite tamgha.

As for the relations between the Alkhans in northwestern India and the Hunnic dynasties north of the Hindu Kush, there is still quite a lot of uncertainty. Hans T. Bakker and other scholars believe that a silver bowl found in the Swāt valley (ancient

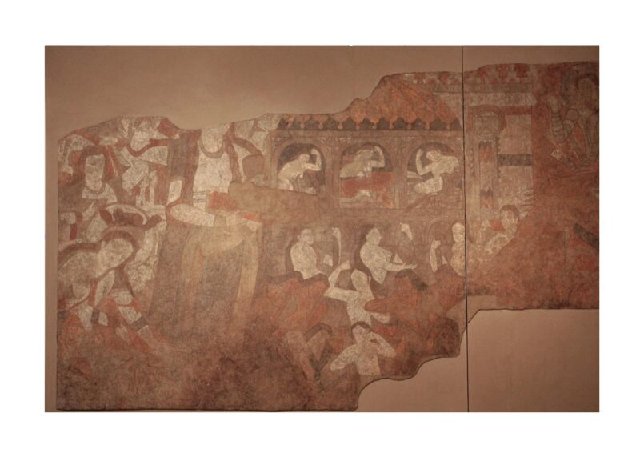

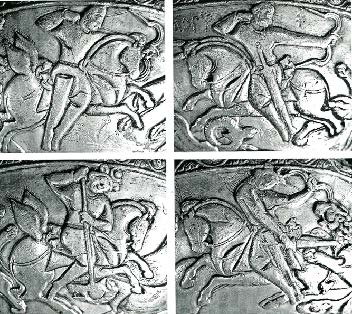

Uḍḍiyāna) north of Gandhāra can shed some light in the relationship between Kidarites and Alkhans during the first half of the V c. CE. The provenance of this bowl is not completely clear. Its discovery was announced to the Society of Antiquaries of London in 1912, when Charles Hercules Read reported that, according to his informant, this vessel had been recovered when “during a flood on the Swāt River part of the bank was washed away”. It may originally have been gilded. Advances in the interpretation of the iconography of the bowl were not made until numismatists examined it closely. They supported tentatively a chronology dating back to the first half of the V c. CE, based on the similarities between the crowns and headgear of the four mounted hunters depicted on the bowl with those that appear on the coinage of Hunnic kings in Swāt and Gandhāra.

The Austrian numismatist Robert Göbl compared the crowns of two of the four hunters with Kidarite coins, one with, the other without korymbos. The third hunter, according to Göbl, displays an elongated skull, comparing it to early Alkhan coins of king Khiṅgila. The fourth hunter, who might be the same one depicted on the central medallion of the bowl, is without crown, which, according to Göbl, was common in early coin issues of Indian Huns, both Kidarite and Alkhan ones. He also supported the chronological attribution to the first half of the V c. CE, which has become accepted by all subsequent numismatists.

There exists to date a general consensus regarding the iconographic interpretation of the bowl from Swāt: it represents a secular scene of a hunt in which princes of two ethnic groups take part, probably Kidarite and Alkhan. According to the historian Elizabeth Errington, the bowl represents the c-existence between Kidarites and Alkhans in the first half of the V c. CE in Gandhāra and Swāt, who may have been in control of different areas at the same period. The bowl also displays a Brahmi inscription near the upper rim, which Hans T. Bakker reads as displaying the Hunnic name

Khiṅgi(la) and a date “206”, that if is taken to have been written according to the Bactrian Era (that starts with the founding of the Sasanian Empire by Ardaxšīr I in 224 CE), would correspond to the year 428-429 CE.

The Swāt bowl, and detail of the four mounted hunters.

Bakker points out that if his reading of the inscription is correct, this could be put in relation with another silver bowl that also displays the name

Khiṅgila. In 1970, an eight-lobed silver bowl was found in the former Northern Wei capital of Dai/Pincheng (today Datong, in Shanxi province) bearing many similarities to the bowl of Swāt and to another similar one (but without inscriptions) found at Chilek near Samarkand, and which displays a Bactrian inscription that reads as “Property of Khiṅgila the lord”. Bakker speculates that this object could have reached the court of the Northern Wei with the 459 CE embassy from

Jiduoluo recorded in the

Weishu. As we will see in later posts, Bakker argues rather convincingly that after the collapse of Kidarite rule in Ṭoḵārestān and its replacement by the Hephthalites, the later placed a ruler over the Alkhan in northwestern India who was named

Khiṅgila and who minted names in his own name, and could have been the same ruler whose name appears engraved in these bowls.

To confuse matters even more about political boundaries and control in Central Asia during the first decade of Pērōz’s rule, there is another interesting document. One of the Bactrian Documents, dated to the year 239 of the Bactrian Era (i.e. to between December 461 CE and January 462 CE) This document is a letter in which a certain

Meyam, king of the

Kadag, calls himself “governor of the famous and prosperous

Šahān Šāh Pērōz”. This

Meyam could be the same person that appears in a seal with a male bust under the Bactrian name

Mēhan. Some scholars have vinculated also this character with the Alkhan king

Mehama, which is listed in the Schøyen Copper Scroll as

mahāṣāhi Mehama. But this association is problematic by several reasons. First, there’s the chronology: the scroll is dated to 492-493 CE (or 495-496 CE), and second, despite the fact that the scholar who first published it in 2006 (Gudrun Melzer) located the

Tālagāna quoted in the scroll with

Tālaqān in eastern Ṭoḵārestān, but in 2007 Étienne de la Vaissière argued convincingly for an Indian (specifically, Punjabi) origin of the scroll, and that the

Tālagāna quoted in it should be identified with

Tālagang in Punjab. Bakker thinks that

Meyam/

Mēhan/

Mehama should be treated as three distinct people: the first and last one are far too separated in time, and we have no secure chronological frame for the second one.

One of the early coins issued in the name of the Alkhan ruler Khiṅgila. On the obverse, bust of Khiṅgila with the Bactrian legends “kiggilo” (left) and “alchono” (right), and the Alkhan tamgha. On the (badly worn out) reverse, fire altar with attendants, a relic from the original Sasanian coinage that the Huns began copying in the late IV c. CE. Tentatively dated to the mid-V c. CE. Notice the elongated skull, displayed in the portraits of all the Alkhan kings.

The interesting bit though is that in 461-462 CE there was a certain local king named

Meyam who ruled

Kadag/

Kadagstān, and declared himself to be Pērōz’s governor (more specifically, MP

kadag-bid, which translates as “master of the royal household”, implying that perhaps this area was considered part of the royal demesne of this Sasanian king), a region located northeast from Rōb, in the area of Baġlan south of Tālaqān, in eastern Ṭoḵārestān. There is another Bactrian Document dated to years later (474-475 CE) in which

Meyam appears again, and still describes himself as being subordinated to Pērōz. In my opinion, this scattered evidence complicates considerably the storyline that seems to have become the current consensus among historians, i.e. that the Sasanian border with the Kidarites stood at the line Marw – Marw-Rūd – Herāt, and that the entire Ṭoḵārestān was under Kidarite control. The strongest proof for this theory is that there are no Sasanian coins of Yazdegerd I, Warahrān V and Yazdegerd II minted in Balḵ or any other Bactrian city, but the fact is that a certain

Meyam (who could be a Hun, as a later Alkhan name bore this same name) ruled over a province/principality in eastern Ṭoḵārestān (well to the east of Balk) in Pērōz’s name. And as we have also seen, there are also hints that the Hephthalites had already broken free from Kidarite rule in eastern Ṭoḵārestān. If we consider both possibilities together (that the Sasanians controlled territory in Ṭoḵārestān as far east within Ṭoḵārestān as Tālaqān and Kadagstān, and that the Hephthalites may have already become an independent force in eastern Ṭoḵārestān (Čaḡānīān, Badaḵšān, and perhaps even Kābolestān), on both banks of the Amu Darya, then the claim of the Perso-Arabic sources that Pērōz handed them Tālaqān, or Termeḏ (or both) in pay for their intervention in the Sasanian war of succession could gain some semblance of plausibility.

The main problem though is that the only literary sources that are roughly contemporary to the events (Łazar P’arpec’i and Ełišē) say nothing about an Hephthalite intervention, and that based on their accounts the eastern wars of Yazdegerd II had been not remarkably successful. In this respect, not much more can be said, but in my opinion is that the evidence seems to point toward a certain degree of Sasanian control deep into Ṭoḵārestān, well to the east of Balḵ. The Bactrian Document of

Meyam dated to 461-462 CE is direct evidence of it, and it cannot be discarded.

It would not be until 464 CE when Pērōz resumed the war against the Kidarites. In the meantime, according to Ṭabarī, he had to deal with a seven-year drought that devastated his territories:

Ṭabarī,

History of the Prophets and Kings;

The Kings of the Persians and the Kings of al-Ḥīra:

He displayed just rule and praiseworthy conduct and showed piety. During his time, there was a seven year long famine, but he arranged things very competently: he divided out the monies in the public treasury, refrained from levying taxation, and governed his people to such good effect that only one person died through want in all those years.

Ṭabarī actually offers two versions of Peroz’s reign, stating that he follows two different sources with differing views:

Another purveyor of historical traditions other than Hishām has stated that Fayrūz was a man of limited capability, generally unsuccessful in his undertakings, who brought down evil and misfortune on his subjects, and the greater part of his sayings and the actions he undertook brought down injury and calamity upon both himself and the people of his realm. During his reign, a great famine came over the land for seven years continuously. Streams, qanats, and springs dried up; trees and reed beds became desiccated; the major part of all tillage and thickets of vegetation were reduced to dust in the plains and the mountains of his land alike, bringing about the deaths there of birds and wild beasts; cattle and horses grew so hungry that they could hardly draw any loads; and the water in the Tigris became very sparse. Dearth, hunger, hardship, and various calamities became general for the people of his land. He accordingly wrote to all his subjects, informing them that the land and capitation taxes were suspended, and extraordinary levies and corvées were abolished, and that he had given them complete control over their own affairs, commending them to take all possible measures in finding food and sustenance to keep them going. He wrote further to them that anyone who had a subterranean food store, a granary, foodstuffs, or anything that could provide nourishment for the people and enable them to assist each other, should release these supplies, and that no one should appropriate such things exclusively for himself. Furthermore, rich, and poor, noble, and mean, should share equally and aid each other. He also told them that if he received news that a single individual had died of hunger, he would retaliate upon the people of that town, village, or place where the death from starvation had occurred, and inflict exemplary punishment on them.

In this way, Fayrūz ordered the affairs of his subjects during that period of dearth and hunger so adroitly that no one perished of starvation except for one man from the rural district of Ardashīr Khurrah, called Dīh. The great men of Persia, all the inhabitants of Ardashīr Khurrah and Fayrūz himself considered that as something terrible. Fayrūz implored his Lord to bestow His mercy on him and his subjects and to send down His rain (or, assistance) upon them. So God aided him by causing it to rain. Fayrūz's land once more had a profusion of water, just as it had had previously, and the trees were restored to a flourishing state.

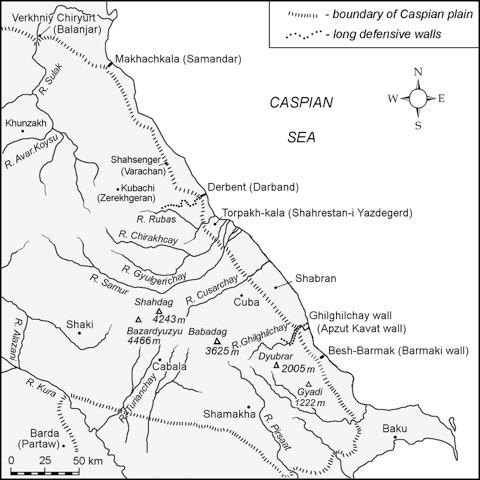

If we assume that Ṭabarī counts here his regnal years starting in 457 CE and not in 459 CE, then seven years is the exact time elapsed between 457 CE and 464 CE, when Pērōz renewed the war in the East. In this precise year or a little latter (464-465 CE), there was a diplomatic row with the Eastern Romans about the matter of the Roman “contribution” to the upkeep of the fortifications in the Caucasus, as recorded by Priscus of Panion:

Priscus of Panion,

Fragment 32, from the

Excerpts on Foreigners’ Embassies to the Romans of Constantine VII Porphyrogenites:

While the fugitive nations feuded against the Eastern Romans, an embassy arrived from Italy, saying that they could no longer resist unless the Easterners reconciled them to the Vandals. An embassy also arrived from the Persian monarch on behalf of Persian fugitives dwelling in the Roman Empire and on behalf of Magi who dwelled in Roman land from ancient times. The ambassadors charged the Romans with wishing to keep these people from practicing their ancestral customs, laws, and religious practices, and so harassing them and not permitting them to perpetually kindle the fire they call unquenchable, as the law required. The embassy also stated that the Romans must provide money and show concern for the fortress Iouroeipaach, which lies at the Caspian Gates, or at least to send soldiers to guard it. The Persians, they said, should not be alone in bearing the expense and the protection of the place. For if they should fail, the neighboring nations’ violence would readily strike not only the Persians but also the Romans. They also said that they must, like allies, supply funds for the war against the so-called Kidarite Huns. If the Persians should succeed, the Romans would benefit from the nation not being permitted to cross into the Roman Empire.

Regarding all these demands, the Romans answered that they would send someone to negotiate with the Parthian monarch. They said that there were no fugitives among them, nor were they harassing the Magi about their religious worship; furthermore, they were not justified in demanding money for garrisoning the fortress Iouroeipaach and for the war against the Huns since the Persians had taken up these activities on their own behalf.

Tatianos, a man enrolled at the rank of patrician, was sent as ambassador to the Vandals on behalf of Italy. Constantius, who had attained the consulship three times and had reached the rank of patrician as well as consul, was sent to the Persians.

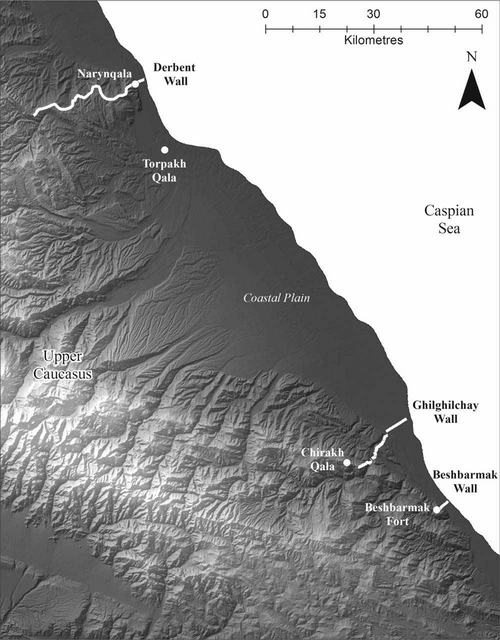

Graeco-Roman sources often mistake the Caucasian passes with each other, so it is unclear if the Sasanian ambassadors were referring here to the fortifications at Darband or at Darial. Sasanian demands for money (or tribute) from the Romans for the upkeep of the Caucasian garrisons, as we have seen, are nothing new, but were always contentious because they were hard to justify by the Roman emperors and the Sasanian court exploited them for their propaganda value as “tribute”. Probably, the death of Attila and the disarray of the western Huns (who, as we have seen in a previous post, were engaged in their own internecine conflicts) were considered by the court of Constantinople as encouraging signs and they refused to pay. What seems to be new (or at least unattested in the sources until now) is Pērōz’s demand for help against the Kidarites, an enemy that was located too far away from the Roman borders for the Eastern Romans to feel threatened by them. It is also thanks to this fragment by Priscus that we know that the enemies Pērōz was about to engage were Kidarites, as the Perso-Arabic sources name them systematically as “Hephthalites”. Fortunately, another fragment by Priscus has survived which narrates the development of the embassy of Constantius:

Priscus of Panion,

Fragment 33, from the

Excerpts on Foreigners’ Embassies to the Romans of Constantine VII Porphyrogenites:

The Persian monarch (i.e. Pērōz) then received into his land the ambassador Constantius, who had remained in Edessa for a time, as I said about his embassy. He ordered him to come while he was occupied not in the cities, but on the border between his cities and the Kidarite Huns. He was engaged in [a war] caused by the Huns’ refusal to take the tribute that past Persian and Parthian kings had agreed upon. His father, having refused to pay the tribute, took up the war and then bequeathed it and the kingdom to his son. Because they kept suffering defeat in battle, the Persians wished to solve the Hunnic problem by deception.

And so, it was said, Peirozes (this was the Persian king’s name at the time) sent messages to Kounchas, the Hunnic leader, stating that, hoping for peace with them, he wanted to agree to an alliance and to offer his sister in marriage; for he happened to be very young and not yet the father of children. Kounchas, it was said, accepted the proposal, but married not Peirozes’s sister, but another woman decked out in royal fashion, whom the Persian monarch sent off after informing her that if she revealed nothing of the deception, she would share in kingship and happiness, but if she revealed the theatrics, she would suffer death as a penalty since the Kidarite ruler would not endure a servile wife in place of a well-born woman.

The treaty thus negotiated, Peirozes did not enjoy his deception against the Hunnic leader very long. Because the woman was concerned that the nation’s ruler would learn of her situation from others and would cruelly subject her to death, she revealed what had been perpetrated. Kounchas praised the woman for her truthfulness and kept her as his wife. He wished to punish Peirozes for his trickery, and so he pretended that he was having a war against neighboring peoples, and that he needed men, not men fit for war (for there were thousands available to him) but men who would be his generals. Peirozes sent him three hundred elite men. The Kidarite ruler killed some, and others he maimed and sent back to Peirozes to report that he had paid this penalty for his deceit.

Thus the war was rekindled, and they fought violently. Peirozes accordingly received Constantius in Gorga (this was the name of the place where the Persians were encamped). After treating him kindly for several days, he sent him away with no auspicious response to his embassy.

This fragment is filled with valuable information. It repeats that it was the Kidarites that Pērōz was fighting against, and that their king was a certain

Khounchas (

Koúγxas), usually transliterated into English as

Kunkhas, a name which some scholars have interpreted as

*Xūnqan (reconstructed Turkic for “Khan of the Huns”), but there’s no consensus about this reading. Priscus also informs us that the Sasanian kings had been paying tribute to the Kidarites, and that it had been Yazdegerd II who had stopped paying it, thus rekindling the war against them, a war inherited by his son. It’s possible that the negotiations for a marriage between Pērōz’s sister and “Kunkhas” would have been undertaken during the difficult years between 459-464 CE, when

Ērānšahr was devastated by drought, as a way to compensate the Kidarites for not paying a tribute that would have been difficult to gather anyway in such situation. The story as such is difficult to believe, because if the initiative for the marriage offer came from Pērōz, attempting such a crude deceit would have been extremely stupid, and especially because it’s an exact parallel to the story/legend of Amasis and Cambyses as told by Herodotus, as noted by Nikolaus Schindel. Alternatively, it is also possible that the war had started with a Sasanian defeat against the Kidarites and that “Kunkhas” had forced Pērōz to agree to a royal wedding, which would perhaps explain such an uncommon story.

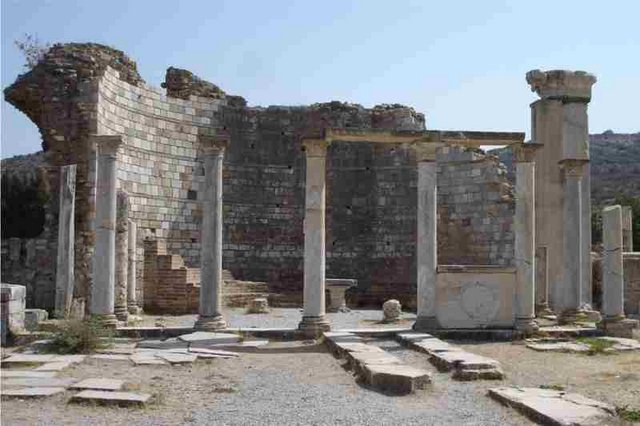

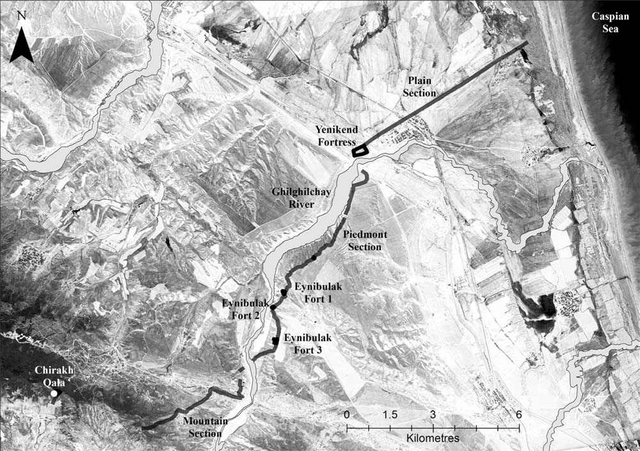

Aerial photograph of the remains of the Great Wall of Gorgān and one of its attached forts.

Another bit of information delivered by this fragment is that Pērōz received Constantius at

Gorga, “the place where the Persians were encamped”. It is almost certain that this place was Gorgān, where Pērōz probably (according to extensive archaeological research conducted during the last twenty years) this king completed the construction of the impressive fortifications of the Great Wall of Gorgān, as well as the tens of fortified encampments located near it. Some of them were large enough to accommodate large armies, and it is almost sure that they acted as the launching point for Pērōz’s campaigns in the East, against the Kidarites and Hephthalites. Joshua the Stylite also supports Priscus’ account (minus the tale about the false bride):

Chronicle of Joshua the Stylite, VII:

Even in our days Pērōz, the king of the Persians, because of the wars that he had with the Kūshānāyē or Huns, very often received money from the Greeks, not however demanding it as tribute, but exciting their religious zeal, as if he was carrying on his contests on their behalf, “that,” said he, “ they may not pass over into your territory”. What made these words of his find credence was the devastation and depopulation which the Huns wrought in the Greek territory in the year 707 (of the Seleucid Era, 395-396 CE), in the days of the emperors Honorius and Arcadius, the sons of Theodosius the Great, when all Syria was delivered into their hands by the treachery of the prefect Rufinus and the supineness of the general Addai.

Notice how the author of this Chronicle (it is uncertain if it was Joshua or not, as it is sometimes referred to as “Chronicle of the Pseudo-Joshua the Stylite”) takes care to underline that the money paid by the Eastern Romans to Pērōz was not tribute, but a precautious measure of self-defense. Joshua also describes Pērōz’s enemies as “Kušāns”, as the Armenian sources do (Armenian and Syriac sources usually employed this term to refer to the Kidarites) but he also describes them as Huns, and links them up with the 395 CE Hunnic incursion through the Caucasus that apparently left a very harsh impression in the Roman eastern provinces.

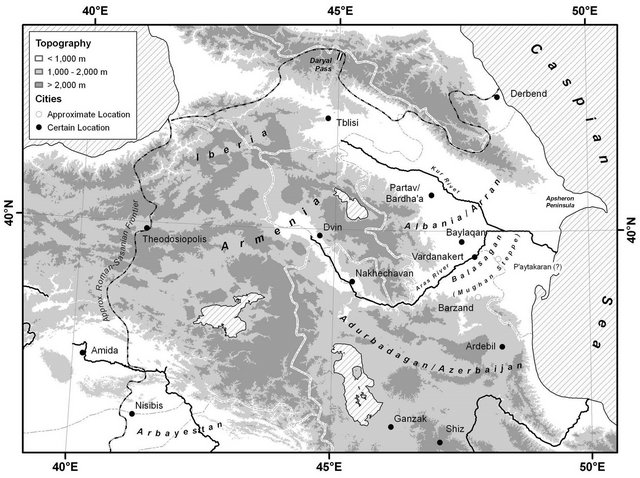

Map of Lazica in Late Antiquity. Notice the location of Suania to its northeast.

While the Sasanian Empire had all its attention centered in the East, the Romans got embroiled in a conflict in the Caucasus that, had the Sasanians not been so distracted in Central Asia, could easily have degenerated into a war between both empires. The area of conflict was Lazica (also called

Colchis by the ancient Greeks), which was the only territory of the southern Caucasus that was not under Caucasian control. It corresponds roughly with the western half of the modern Republic of Georgia and the territory of Abkhazia. The Romans went to great pains to keep this remote corner of land out of Sasanian control in order to deny their foes a naval base in the Black Sea that could have turned into a direct menace for Constantinople. In the 460s CE, the small (but strategically important) kingdom of Suania succeeded in breaking away from Lazic control, an event which was to have repercussions in negotiations between Rome and Persia a century later. There were stirrings too in Sasanian-controlled Armenia, where Vahan Mamikonian, nephew of the rebel leader of 450-451 CE, sought help from the Romans. Although emperor Leo I agreed to lend his support, none was forthcoming. In the VI c. CE, Lazica would figure as one of the main objects of dispute between Romans and Sasanians. We know about this localized conflict thanks to Priscus of Panion:

Priscus of Panion,

Fragment 25, from the

Excerpts on Romans’ Embassies to Foreigners of Constantine VII Porphyrogenites:

After the Romans went to Kolchis and fought the Lazi, the Roman army returned to their stations and the emperor’s retainers began preparing for another campaign. They debated whether they would initiate the war by taking the same road or the road through Armenia that borders Persia if they could first prevail upon the Parthian monarch with an embassy. They thought it was completely impracticable to sail along the difficult coast since Kolchis lacks a harbor. Gobazes himself sent ambassadors to the Parthians, and also sent ambassadors to the Roman emperor. The Parthian monarch, since he was fighting a war against the so-called Kidarite Huns, turned away the Lazi who were fleeing to him.

Priscus offers no chronological frame for this fragment, except that it happened during the reign of Marcian (450-457 CE), as we will see later, so it should be dated to the very end of the reign of Yazdegerd II (more on this below). Notice how

Gobazes, the king of Lazica, tried to get the Sasanians to intervene, but they refused due to their ongoing war against the Kidarites.

Priscus of Panion,

Fragment 26, from the

Excerpts on Foreigners’ Embassies to the Romans of Constantine VII Porphyrogenites:

Gobazes sent ambassadors to the Romans. The Romans replied to the ambassadors sent by Gobazes that they would refrain from war if Gobazes himself gave up his power or at least if he deprived his son of the kingship. It violated longstanding law, they said, for both men to govern the land. So Euphemios, who held the office of magister, proposed that one of them rule Kolchis, Gobazes or his son, and that the war be resolved like that. Euphemios, who was admired for his intelligence and rhetorical excellence, managed Emperor Marcian’s affairs and guided him through many good deliberations. He also took Priscus the historian to share in the concerns of his office.

Given the choice, Gobazes chose to hand over the kingship to his son and give up the symbols of his power. He sent messengers to the Roman ruler to ask that, now that only one Kolchian was governing, he no longer took up arms in anger against him. The emperor ordered him to cross into Roman territory and to give an account of his decisions. He did not refuse the meeting, but he asked him to give Dionysios, the man long ago sent to Kolchis to negotiate with Gobazes, as a pledge that he would do nothing irreversible. Therefore Dionysios was sent to Kolchis and they came to terms over the disputes. Marcian’s ability to send his major ambassadors to minor hotspots perhaps indicates the sense of relief the Romans experienced after the death of Attila. With the Hunnic Empire quickly dissolving, attention could be turned elsewhere. The same was true in the West. There, though, instead of focusing on the many pressing problems such as the Franks’ continuing immigration or the Vandals’ hold on North Africa, attention turned inward and became dissension.

And there is still a third fragment covering this minor episode:

Priscus of Panion,

Fragment 34, from the

Excerpts on Foreigners’ Embassies to the Romans of Constantine VII Porphyrogenites:

After the city was burned in the time of Leo, Gobazes came with Dionysios to Constantinople wearing Persian dress and attended by bodyguards in the Median manner. When the courtiers received him, at first they censured his rebellion, but then sent him away cordially because he captivated them with his flattering words and by wearing Christian tokens.

The conflict in Lazica began under Marcian and ended under Leo I; the transition between one emperor and the other happened in 457 CE, the same year of Yazdegerd II’s death, so this final fragment should be probably allocated to the reign of Pērōz (during the civil war against Hormazd III). Some scholars think that Gobazes’ Persian dress may be significant. As Priscus stated earlier, the Lazi had rebelled against their status as a Roman client kingdom and had asked for Sasanian help. The Sasanian court refused at first, but the “Persian dress” and protocol (i.e. the “Median guard”) displayed by Gobazes could hint at a Sasanian acceptance of Gobazes’ offer, so that he now enjoyed some degree of “protection” from Pērōz, although this would push this trip of Gobazes to Constantinople quite forward in time, until Pērōz had achieved final success against the Kidarites, as it seems quite unlikely that otherwise the Sasanians would have risked a war against the Eastern Romans while they were still fighting in Central Asia. The end result of these disputes between the Suani and their traditional overlords, the Lazi, was thus that the latter were brought into alignment with the Sasanians, while the former retained their independence and their loyalty to the Romans.

Landscape of the Caucasus Mountains in the modern region of Svaneti in the Republic of Georgia, which corresponds roughly to ancient Suania.

Although Ełišē and Łazar P’arpec’i did not mention anything about a war between Pērōz and the Kidarites, some scholars see in their accounts of events a hint of that conflict. As we have seen in a previous post, the Armenian rebel nobles were liberated and sent to Herāt on the sixth regnal year of Pērōz, and this would have to bee seen in the context of the Sasanian war against the Kidarites. According to the German historian Andreas Luther, this conflict may have begun in 457 CE and would have lasted until 462-463 CE, and according to this chronology Luther proposed to date the agreement between Pērōz and “Kunkhas” to 462 CE, kept the date for Constantius’ embassy to 464-465 CE and proposed that a new Sasanian defeat would happen in 465 CE, which would lead to the captivity of Pērōz’s son Kawād in 465-467 CE (we’ll talk about this later). It is also interesting to notice that in his 1997 translation of the

Chronicle of Joshua the Stylite, Luther read

Kyonāye (i.e.

Chionites) instead of

Kūshānāyē, although Luther’s reading is not accepted by everybody, and the old reading by Wright is still accepted. The most accepted view nowadays is that the final war between Kidarites and Sasanians began (or rather restarted) after Kunkhas’ “revenge” and carried on until 467/468 CE, and ended with a total victory by Pērōz, who destroyed the Kidarite empire.

Priscus of Panion,

Fragment 41, from the

Excerpts on Foreigners’ Embassies to the Romans of Constantine VII Porphyrogenites:

As the Romans’ and Lazi’s dispute with the Souani was very great and the Souani vehemently fought against […], and as the Persians wished to make war on him because of the fortresses that had been taken away [by] the Souani, he sent an embassy, asking the emperor to send him reinforcements from among the soldiers who were guarding the boundaries of the Armenians who paid tribute to the Romans. Since they were near, he said, he would thereby have ready assistance and not be in peril while anxiously awaiting men coming from afar. Moreover, since they were close, he would not be beset by their expenses if by chance the war were delayed, as had happened before. When Herakleios had come with help against the Persians and the Iberians who were making war on him, he became preoccupied in fighting other nations and dismissed his allies because of the burden of supplying their provisions. So when the Parthians turned their sights toward them, he called in the Romans again.

After they promised to send help and a commander, a Persian embassy also arrived, announcing that they had defeated the Kidarite Huns and had forced their city Balaam to surrender. They publicized the victory and boasted about it in barbarian fashion, wishing to demonstrate how much power they had at the time, but the emperor dismissed them as soon as the news was announced, since he was deep in thought about Sicilian events.

This fragment is key and is the one that is the main proof for modern historians about the fate of the Kidarites. Based on the other events described in this fragments in the Caucasus and in Sicily (which had been occupied by the Vandals), it has been dated securely to 467-468 CE. And it is usually assumed that the city

Balaam (

Βαλαάμ) refers to Balḵ, the capital city of Ṭoḵārestān, but there are doubts about it. Some scholars, like János Harmatta, Evgeniy V. Zeimal or Frantz Grenet, identified it with Balḵ. But others (like Josef Marquart and Geoffrey Greatrex) have identified it with the Balxān province in western Turkmenistan, on the shore of the Caspian Sea. And still Andreas Luther located it near Marw. The option that

Balaam is not identical with Balḵ was also supported by Kazuo Enoki, as he thought that by this time the Hephthalites would have already pushed the Kidarites out of Ṭoḵārestān. But there are powerful reasons to identify it with Bal

k. The place of Igdy Kala, that the scholars mentioned above would have been the Kidarite capital in Balxān seems to have been actually just a fort built and occupied during the Arsacid era (see the chapter about Khwārazm in the second thread). Another problem is the identification of Priscus’

Balaam with the

Boluo quoted in Chinese sources, which is said to be a Kidarite city and which has been identified with Balk, Balxān or a city to the west of Bāmīān by some historians.

Scyphate dinar of Pērōz minted in Balḵ.

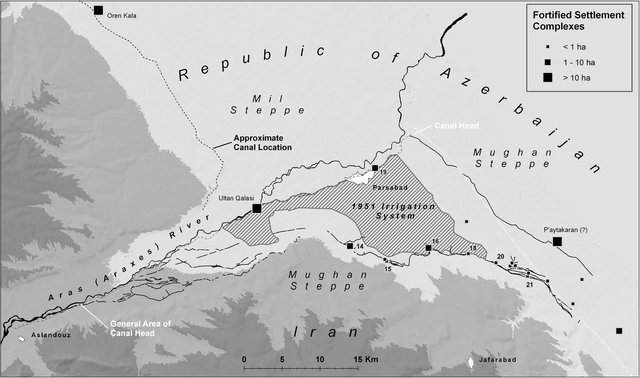

This Sasanian victory has been also associated with a coin and a seal by Pērōz. The coin is a rare gold issue minted in Balḵ, following the Kušān and Kidarite model of scythed dinars. In this coin, Pērōz is depicted with his second crown and with a legend in Bactrian that reads “Pērōz, king of kings”. This second crown by Pērōz is the one that Pērōz began to display after his victory against Hormazd III, and which he would keep until 474 CE, when Pērōz was defeated by the Hephthalites and the mint of Balḵ was captured by them.

Pērōz announced his victory far and wide. For starters, he started displaying again in his great seal the legend

Šahān Šāh Ērān ud Anērān that had been abandoned by the Sasanian kings after Šābuhr III’s reign, signaling that he had finally managed to reassert Sasanian rule over the lands of

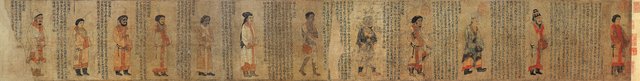

Anērān. And just as he had sent an embassy to Constantinople to announce his victory, he also sent embassies to China. Sasanian diplomacy had been very active in Chine during this final stage of the war against the Kidarites; there had been Sasanian embassies (embassies from

Bosi, as the Chinese called Iran) to the Northern Wei in 455 and 461 CE, but Pērōz sent two more embassies, very close in time, to the court of emperor

Xianwen of Wei (465-471 CE) in Pingcheng, in 466 and 468 CE. The second one probably announced the final Sasanian victory to the Wei.

Joshua the Stylite confirms the Sasanian victory, although he adds more details:

Chronicle of Joshua the Stylite, X-XI:

By the help of the money which he received from the Greeks, Pērōz subdued the Huns, and took many places from their land and added them to his own kingdom; but at last he was taken prisoner by them. When Zenon, the emperor of the Greeks, heard this, he sent money of his own and freed him, and reconciled him with them. Pērōz made a treaty with the Huns that he would not again cross the boundary of their territory to make war with them ; but he went back from and broke his covenant, like Zedekiah, and went to war, and like him he was delivered into the hands of his enemies, and all his army was destroyed and dispersed, and he himself was taken alive. He promised in his pride that he would give for the safety of his life thirty mules laden with silver coin|; and he sent to his country over which he ruled, but he could hardly collect twenty loads, for by his former wars he had completely emptied the treasury of the king who preceded him. Instead therefore of the other ten loads, he placed with them as a pledge and hostage his son Kawād, until he should send them, and he made an agreement with them for the second time that he would not again go to war.

When he returned to his kingdom, he imposed a poll- tax on his whole country, and sent the ten loads of silver coin, and delivered his son. But he again collected an army and went to war; and the word of the Prophet was in very reality fulfilled regarding him, who says, “I saw the wicked uplifted like the trees of the forest, but when I passed by he was not, and I sought him but did not find him”. For when a battle took place, and the two hosts were mingled together in confusion, his whole force was destroyed, and he himself was sought but not found; nor to the present day is it known what became of him, whether he was buried under the bodies of the slain, or threw himself into the sea, or hid himself in a cave underground and perished of hunger, or concealed himself in a wood and was devoured by wild beasts.

According to this second account, Pērōz was first defeated by the Kidarites, had to leave his son Kawād as a hostage, he released him and then he went to war again, obtaining victory. This first defeat could be the one mentioned above in Luther’s proposed chronology, also accepted by other scholars like Nikolaus Schinkel. It’s within the frame of the sustained Sasanian pressure by Yazdegerd II and Pērōz (almost continuous state of war between 442 and 467-468 CE) that Frantz Grenet and Étienne de la Vaissière proposed to situate the great construction and fortification effort of the Kidarites in Sogdiana (which Grenet dated to the period 440-470 CE), as well as the arrival of Bactrian influences in Sogdiana, that both French historians see as “refugees” fleeing Ṭoḵārestān, which was apparently the main theater of war. Also it’s within this context that we should see the appearance of the Hephthalites in eastern Ṭoḵārestān; in 456 CE they were already noticeable enough to send an embassy to the Northern Wei, and if we are to believe the Perso-Arabic sources, strong enough to intervene in the Sasanian war of succession in 457-459 CE. It is also within this context that we should understand the “Indian episode” of the war between the Gupta emperor Skandagupta (r. 455-468 CE) and the Huns, which should be probably dated to the early to middle 450s, after Yazdegerd II’s defeat in 453 CE, but which could have failed (among other reasons) by the emergence of the Hephthalites in eastern Ṭoḵārestān, which, together with the renewed Sasanian pressure after Pērōz defeated his brother Hormazd III. I’m also unsure about what would have been the situation in Ṭoḵārestān after Pērōz’s conquest of Balḵ in 467-468 CE. This conquest is certain, because Pērōz minted coins there: gold dinars in Kushano-Sasanian style, describing himself in the legends as “Great Kušān King”, but I am not so certain about the status of the rest of the country. It is usually assumed by historians that most of the Kidarite territory was overtaken by the Hephthalites, but as we have seen still in 474-475 CE the king of Kadagstān called himself “the governor” of Pērōz, and Kadagstān is located quite to the east of Balḵ, so it seems that at least south of the Āmu Daryā the Hephthalites (in the aftermath of Pērōz’s victory in 467-468 CE) may have controlled little more than what I described above: Kondūz, Badaḵšān and perhaps the Kābolestān (Čaḡānīān is located north of the river). Historians also write about an alliance between Pērōz and the Kidarites, but this is not actually attested anywhere, it is only an extrapolation from the fact that allegedly they may have helped him defeat his brother in 457-459 CE. It is of course possible that both the

Šahān Šāh and the Hephthalites were waging war against the Kidarites at the same time but having a firm alliance between them is another matter altogether.

Seal of the Sasanian king Pērōz, wearing his third crown.

As we have seen though, the defeat in 467-468 CE did not represent the end of the Kidarites. They ceased being an empire and a threat to

Ērānšahr, but some Kidarite-ruled territories remained in existence in northern India, in

Jilin, from where they still sent an embassy to the Wei in 477 CE. Kazuo Enoki thought that Jilin referred to Swāt or the Punjāb, but Xiang Wan thinks that it refers to Kashmir. These embassies are recorded in the

Weishu as having been sent by

Jiduoluo, which was the Chinese transcription of

Kidāra, so there’s little doubt about their political adscription. The case of Sogdiana is more complicated. Several embassies from

Sute (Sogdiana) to the Northern Wei are recorded in the

Weishu in 435-479 CE, and

Xiwanjin (Samarkand) sent embassies in 473-509 CE, from this late date onwards such embassies change and start to describe themselves as Hephthalite. The interpretation of this phenomenon is disputed. Kazuo Enoki thought that the Hephthalites had already occupied Sogdiana between 473 and 479 CE, but that there was freedom to send embassies to China without the compulsion of acknowledging Hephthalite rule, but Shoshin Kuwayama thought that this may show that Samarkand did not fall to the Hephthalites until 509 CE, and that the time elapsed between the first Hephthalite embassy to the Wei (456 CE) and the second one (507 CE) represents the time the Hephthalites spent at war in Ṭoḵārestān and Sogdiana against the Sasanians and Kidarite resistance.

Khodadad Rezakhani also thinks that a Kidarite kingdom may have survived in Sogdiana, possibly in the area of Osrušana. The legend on the famous Kidarite seal found near Samarkand reads:

Lord Ularg the King of the Huns, the Great Kušān Šāh, the Afšiyan of Samarkand.

The title of

Afšiyan is a rendition of the well-known Islamic title of

Afšin, for kings of Osrušana is akin to other titles from the region originating from Old Iranian

*xšaita-, which also renders MP

Šāh. The seal thus shows the position of a king of the Huns, with claims to the position of

Kušān Šāh, living in Samarkand, a situation that matches well our other evidence for the presence of the Kidarites in Sogdiana. However, Rezakhani thinks that we should not assume that the Kidarite presence in eastern Sogdiana disappeared quickly after their demise in Ṭoḵārestān. Indeed, centuries later, in the early IX c. CE, the local king of Osrušana and the Abbasid general Al-Afšīn bore the personal name of

Khydhar (Ṭabarī IX.11), which was sometimes transcribed as

Haydar in Arabic (as in Dīnawarī) but was specified as

Khydhar by later writers as well, while at least one source has the form

Kydr. The name

Kydr seems to have indeed been a popular one among the people of Osrušana, as several characters bearing it, including a certain

Kydr ibn ‘Abd-Allāh al-Osrušanī, are mentioned in the Islamic sources like Ṭabarī or Ya’qūbī. This might also be related to the

Afšun,

Khuv of Khāhsar who is mentioned on one of the documents from the Moḡ Mountain as the addressee of a rather unhappy letter from 722 CE by Dēwāštič, the ruler of Panjikant and the last opponent of the Muslim conquest of Sogdiana.

Compilation of the crowns worn by Sasanian kings as shown in their iconography. From “The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 3: The Seleucid, Parthian, and Sasanian periods (Part 1)”. Collection of essays from several authors, edited by Ehsan Yarshater.