5.4 THE GREAT WALL OF GORGĀN.

I have mentioned the Great Wall of Gorgān repeatedly in previous posts, but deliberately I have withheld any further comment on the subject because I thought that it deserved to be explained and explored in length and not in a passing commentary. Located in what is today Golestān Province in northern Iran, it is the second longest continuous wall in the Late Ancient world after the Great Wall of China, and it extended along 195 km from the westernmost slopes of the Ālādāgh Range (which is itself a western offshoot of the larger Koppeh Dagh Range that separates the Iranian Plateau to the South from the Turanian Basin to the north) along the valley of the Gorgān River, until reaching the shore of the Caspian Sea. The wall itself was 6-10 m wide, with over 30 fortresses at intervals of between 10 and 50 km, and with a substantial moat than ran parallel to the wall on its northern side and was filled with water of the Gorgān River. A substantial part to the west appears to be buried under marine sediments under the Caspian Sea (it is supposed that the water level of the Caspian was lower back in Sasanian times, as something similar has been noticed at the Darband Wall). It could even be linked up undersea with the similar Tammīšeh Wall, another linear barrier of similar design and built with the same type of bricks built to its west, closing the Caspian lowlands as a north-south barrier, from the Caspian shore to the Ālborz Mountains.

Satellite view of the southern Caspian Sea Shore, looking west. The widening green plain in the lower right corner is the Gorgān Plain, and the mountain chain in the center of the picture is the Ālborz Range, which separates the lowlands of the Caspian Sea from the Iranian Plateau to the south (left in the picture).

Nowadays, practically nothing remains of it at ground level, as most of the wall was made with fired bricks that were systematically looted by the local population across the centuries. The wall also runs through fertile agricultural flatlands, and many sections have been tilled over repeatedly over the centuries. But despite all these factors, it is still visible by the naked eye in the landscape, as the limits of land plots tend to follow its course, and the massive moat in front of it has not been filled in most places. Its trace becomes even more obvious and visible from the air and on satellite images, where it forms a very visible feature of the landscape. In Iranian lore, it has usually been referred to as “Alexander’s Wall”, as the Macedonian conqueror was described as a wall builder in the Qur’an and the Šāh-nāma, and also (less often) as “Anuširwān’s Wall” (after the Sasanian king Xusrō I) or “Pērōz’s Wall”, while the local Turkmen population called it “The Red Snake” (Qizil Alan, due to the red color of its fired bricks). It was abandoned sometime during the first half of the VII c. CE, as the Sasanian Empire became embroiled in its last great war against the Romans which was followed by its disintegration and the Muslim conquest soon thereafter.

The valley of the Gorgān River is (as I have said before) a fertile, well-watered and easy to cultivate area, and so it has been inhabited by agriculturalists since the Neolithic. Historically, it has been part that the region known by Classical geographers as Hyrcania, which also included the southern shore of the Caspian Sea to an undetermined limit to the west. It formed a satrapy under the Achaemenids, with its capital at Zadrakarta (located at the site called Qal’eh-ye Ḵandān or perhaps at the modern city of Gorgān. Confusingly, the Sasanian city of Gorgān does not coincide with the modern city of the same name (which was known as Astarābād before the mid-XX c.) but corresponds either to the modern town of Gonbad-e Kāvūs, located directly by the Gorgān River, or to the nearby Sasanian ruins at the site known as Dašt Qal’eh.

Properly speaking, the Gorgān Plain is the name of the flat land that stretches from the southern bank of the Gorgān River to the foothills of the Ālborz Mountains. The flat land continues across the Gorgān River, but it is usually called Gorgān Steppe here, as far as the southern bank of the Ātrak River, that runs roughly parallel to the Gorgān River to its south and in this part of the country acts as the border limit between the Islamic Republic of Iran and the Republic of Turkmenistan. North of the Ātrak, the steppe becomes dryer until it turns into the Karakum Desert all the way to the lower course of the Āmu Daryā and the Ustyurt Plateau to the north. The soil of the Gorgān Plain and Steppe is formed by fine loess deposited there after the glaciations of the Pleistocene, and is very prone to erosion; due to this all the rivers have ended up excavating relatively deep riverbeds through it, non-paved and human pathways usually end up becoming trenches (which has eased greatly the task for archaeologists and researchers when trying to reconstruct the ancient settlement patterns of this area).

The different climate and settlement areas in the Gorgān region (image taken from “Persia’s imperial power in Late Antiquity. The Great Wall of Gorgān and frontier landscapes of Sasanian Iran”, edited by Eberhard W. Sauer, Hamid Omrani Rekavandi, Tony J. Wilkinson and Jebrael Nokandeh).

The amount of rain received by the land decreases sharply following a south-north gradient, with the Gorgān River roughly being the limit between the lands where sedentary agriculturalists are attested, while settlement in the steppe to the north of the river has been more sporadic and dictated by climate changes and political circumstances. In the Sasanian era, the Caspian Sea underwent a regression event (known as the Derbent or Darband Regression) and its level was quite lower than it is today; this marked probably its lowest level between the two maximum reached around 500 BCE and the XIV-XV c. CE. Due to this, the western part of the steppe, closer to the Caspian seashore, displays several saline flatlands where only vegetation adapted to salt-ridden soils can grow, and where agriculture is not possible. The movements of the Caspian seashore also have left other marks on the landscape, like sand dunes and small cliffs where the ancient seashore used to be. Apart from the main south-north rain gradient, there is also an east-west gradient, with the eastern part of the Gorgān Steppe receiving more rainwater than the western part.

In 2007, Iranian and British archaeologists began the Gorgān Wall Survey (GWS), on which our current state of knowledge of the Great Wall of Gorgān and its environment rests. Previously, the Iranian archaeologist Mohammad Kiani had conducted an important field research which included the drawing of an excellent and very accurate set of maps of the area, but GWS employed satellite images, mainly from the CORONA satellite system taken in the 1960s and that were declassified in the 2000s as well as other satellite systems, and which offered excellent aerial pictures of very great resolution before the great changes to the landscape suffered since then by the increases in population density, the extension of irrigation networks and the deployment of heavy machinery for agrarian improvements. The results of the GWS were later published in a book, Persia’s imperial power in Late Antiquity. The Great Wall of Gorgān and frontier landscapes of Sasanian Iran, edited by Eberhard W. Sauer, Hamid Omrani Rekavandi, Tony J. Wilkinson and Jebrael Nokandeh, and published by Oxbow Books. Most of the information and maps that displayed in this chapter come from this book.

The results of the survey show that the settlement north of the Gorgān River peaked in the Late Iron Age (ending with the Achaemenid era) and concentrated (as was to be expected) on the eastern part, which receives more rainfall. Archaeologists though are unsure if these settlements should be ascribed to active colonizing policies encouraged by the Median and Achaemenid Empires or to spontaneous settlement of nomadic populations, a pattern well attested historically in Iran and the Middle East. Settlement also peaked on the western part of the steppe, but at a lower density, and thanks to the building of two large irrigation canals that drew water from the Gorgān River. The river itself has also shifted course repeatedly during historical times in its lower course, as this is a seismically active area, and several of these ancient riverbeds were identified during the survey.

Another satellite image, with the position of the modern city of Gonbad-e-Kāvūs on the Gorgān River. The Alborz Mountains merge to its southeast with the Ālādāgh Range that then runs on a southeast course forming the northern limit of Khorasan. The Koppeh Dagh Range runs parallel to the Ālādāgh Range to its north, and the upper valley of the Ātrak River separates both mountain chains. The region to the north of Gorgān and to the west of these mountains is Dihistān.

Gorgān and the steppe region immediately north to it (Dihistān) were the home of the Aparni tribe of the Saka tribal confederation, a group of which eventually moved south crossing the Alborz Range and settling in the Seleucid satrapy of Parthia in the III c. CE under the leadership of Aršak. The first Arsacid capital, know to archaeologist as Old Nisa (ancient Mithradatkert) was located to the east of the Gorgān Steppe, on the foothills of the Koppeh Dagh (today in southern Turkmenistan, very near the Iranian border), and some modern scholars have related the depopulation of the steppe north of the Gorgān River to the displacement of the Arsacid capital to Hekatompylos (its remains are located at Šāhr-e Qūmes to the west of Dāmḡān) in Parthia proper further to the south in the Iranian Plateau.

But the survey has revealed that at the time of the construction of the wall, the steppe north of the Gorgān River was mostly uninhabited or very scarcely settled, despite the finding of administrative bullae and the writings of X c. CE Islamic geographers that attest to the existence of Sasanian/Iranian settlements in Dihistān, the survey has failed to locate substantial traces of them between the Gorgān and Ātrak rivers during the V-VI c. CE. Thus, even if the Sasanian kings claimed their rule over territories located to the north of the Gorgān River, the lands cultivated by sedentary agriculturalists ended at this river, that acted at the time as a sort of border between the sedentary and nomadic worlds. There were also two other important factors that probably influenced the decision to have it built in this location: this is the pace the place where the Ālādāgh Mountains are closer to the Caspian Sea, and where the Gorgān River helped with the building process and also offered an easy way to supply the garrison of the wall with water.

During the survey, the archaeologists discovered that the trace of the wall was mainly influenced by hydraulic considerations, i.e. that the wide moat (actually a proper canal) that ran in front of the wall kept enough of a gradient to channel the water to the Caspian in a controlled way. In this, the Great Wall of Gorgān actually resembles more in its conception the linear water defenses of Mesopotamia (like the “Ditch of Šābuhr” built by Šābuhr II to protect Āsūrestān against A’rab raids on the western bank of the Euphrates) than to other linear barriers like the Darband Wall, the Wall of Hadrian or the Great Wall of China. The trace of the wall was thus determined by the trace of the canal/moat/ditch in front of it, and three connecting canals were built carrying water from the upper course of the Gorgān River to feed it. these canals had to cross river valleys in some cases (of the tributaries of the Gorgān River in its upper course), so aqueducts had to be built to keep an optimum hydraulic gradient. The survey determined that the eastern end of the wall was prolonged 15 km into the Ālādāgh Mountains, and ends in a heavily wooded region, against a steep rock cliff, atop of which the remains of a Sasanian building (probably a fort) were detected. In this part of its trace, the terrain is too steep for a moat, so the wall actually runs south of the Gorgān River, that acts as a natural moat in front of it.

Before entering the plain, the wall crosses over the Gorgān River and then continues its trace all the way to the Caspian seashore to the north of the river. Nowadays, the lower course of the Gorgān River deviates to the southwest after passing the town of Gonbad-e Kāvūs, but in Sasanian times the riverbed followed closely the trace of the wall, quite further north. In the 1930s, the American geologist Lester Thompson noted that along the entire trace of the wall across the plain, the moat formed a continuous ditch of 8-9 m. wide and 2 m. deep. The land displaced in order to dig the moat was used to erect a large linear earthwork that was located directly behind the wall, and to manufacture the fired bricks the made was built with. Due to the lack of wood or stone in the plain, the wall had to be built with bricks, but unlike in Mesopotamia, mudbricks could not be used as they would have lasted only a few years under the winter rains in this environment, so fired bricks were the only alternative. As they had to be produced as near to the building place as possible, thousands of kilns were built (which were located during the survey) along the wall to produce the 100-200 million bricks necessary for the construction of the wall. The canal/moat provided the water necessary and perhaps also allowed for the transportation of supplies for the kilns and the building crews. The result of this is that until the recent massive disruption of the site in the latest decades, the remains of the wall actually resembled three parallel obstacles: the outer embankment, the moat/canal bed, and the inner embankment on which the wall was built. And as a last line of defense, the Gorgān River followed closely the trace of the wall to its south (which became a further ditch after the lower course of the river moved).

Map of the Gorgān Plain showing the ancient riverbeds of the Gorgān River and the old irrigation channels dated to the Bronze Era that had been long abandoned when the Wall was built (image taken from “Persia’s imperial power in Late Antiquity. The Great Wall of Gorgān and frontier landscapes of Sasanian Iran”, edited by Eberhard W. Sauer, Hamid Omrani Rekavandi, Tony J. Wilkinson and Jebrael Nokandeh).

The bricks were all produced following exactly the same pattern: square in plan (40x40 cm, approx.) and 7-8.5 cm. high. The fact that the wall was built with fired bricks in a landscape that is otherwise barren of building materials has been the main reason for the poor state of preservation of the wall: for centuries, the local population robbed the bricks for other uses, until only the foundations were left. In the eastern section of the wall, the best-preserved section found by the section contained thirteen courses of bricks, to a total height of 1.47 m. In all the excavated trenches, the wall proved to be five bricks wide (2 m). In the plain, this 2 meters-thick wall was then abutted on its southern side by a large earthwork made with the earth extracted from the moat’s ditch that had not been used for making the bricks of the wall. Obviously, once the wall entered the rocky landscape of the Ālādāgh, where there was no moat, this earthwork behind the wall is also absent. The collapse of this earthworks northwards as the wall was robbed from its bricks is what has allowed the lower courses of bricks in the lower parts of the wall to survive.

Due to this robbing out process, archaeologists have no way of knowing for sure how tall the wall might have been, although they consider that it may have been quite similar in this respect to the (better preserved) Tammīšeh Wall further west. All sections of the wall (even in the Ālādāgh Mountains) were built using the same type of fired brick, and with no bonding other than mud. Archaeologists also have no clue about how the parapet of the wall might have looked like, or even if it existed at all. In the plain section, where there is the earthwork behind the wall, archaeologists have suggested that this earthwork could have been paved on its top with fired bricks and acted as a communications road behind the wall, either at the same height of the parapet, or slightly under it. That would explain the obvious absence of a road along the wall on its southern sider, as it was common in the Roman border walls, and as it would have been necessary in order to allow the garrisons to displace themselves quickly to any spot under menace. Due to the light loess soil in the area, even if such a road had been unpaved, it would have quickly become a ditch and it would have left visible traces in the landscape.

Easternmost track of the Gorgān Wall, showing how it changed course from being north to south of the Gorgān River (image taken from “Persia’s imperial power in Late Antiquity. The Great Wall of Gorgān and frontier landscapes of Sasanian Iran”, edited by Eberhard W. Sauer, Hamid Omrani Rekavandi, Tony J. Wilkinson and Jebrael Nokandeh).

East of the Pīš Kamar Rocks, where the wall leaves the plain, the earth bank at the bank of the wall disappears, even though there is still a dry moat in front of it, which also disappears in front of it. Archaeologists think that in this part of the wall, the top of the wall must have been three or four bricks wide at the top (1.20-1.60 m), far too narrow to allow for a parapet or a walkway, and think that some sort of wooden scaffolding behind the wall might have been a possibility. And there is still a further possibility to be considered: that the wall lacked indeed any parapet or walkway and that it acted just as a demarcation line. In this respect, it is worth nothing that the survey unable to elucidate if there were interval towers along the wall. CORONA satellite images from the 1960s seem to show small mounds adjacent to the wall, near Fort 8, but these remains are still unexcavated. Archaeologists though warn that towers, especially if they were built on an elevated earthwork base, could have been robbed out of bricks all the way to their foundations, which would make them difficult to detect. Only one interval tower was located by the archaeologist J. Nokandeh, and the survey was able to locate another one later at the Tammīšeh Wall.

The conclusion of the members of the survey was that the wall had not been designed to be an insurmountable obstacle in itself, but that its purpose was to bring small-scale raiding to a halt and to turn any large-scale attacks into dangerous and difficult enterprises. Given that any attackers from the north would have been a cavalry army, and possibly nomads (although this conclusion of the surveyors does not really apply to the Hephthalites, who were far from being “real” nomads), even if they managed to climb the wall, they could not bring their horses with them, and any attack that would have wanted to breach the wall would have needed the use of siege machines like rams, difficult to use given the wide and deep moat and the fact that the wall was well cushioned by the earth mound on its back. Mining would also have been easily detected by the defenders in the flat and bare landscape of the steppe, and the nature of the loess soil would have made the mining in itself quite risky. In short, breaching the wall would have needed the attack of a large army, with the establishment of large-scale siege operations, that conceivably would have given the Sasanian defenders time to react and prepare countermeasures.

But rather than simply its design or construction, the real interest of the Gorgān Plain Survey lies in the fact that it has shed new light onto the organization and numbers of the Sasanian army of the V c. CE, and as a consequence, on the very nature of the Sasanian state itself. Over thirty forts separated about 5-6 km from each other, have been detected along the wall through satellite images, of which Fort 4 was chosen to conduct a more thorough archaeological study.

Remains of two of the canals that fed the moat of the Gorgān Wall (image taken from “Persia’s imperial power in Late Antiquity. The Great Wall of Gorgān and frontier landscapes of Sasanian Iran”, edited by Eberhard W. Sauer, Hamid Omrani Rekavandi, Tony J. Wilkinson and Jebrael Nokandeh).

The reason for this choice was the mound of this fort was the best preserved along the wall, probably due to the existence of a small burial ground on its top, which had caused it to be left undisturbed. As a contrast, Forts 28 and 33, which are perfectly visible on the CORONA images, had been completely flattened by the time the survey took place. The forts along the wall in the plain followed a standard plan, of which Fort 4 is a representative example, although not all of them were of the same size.

Fort 4 was built on a raised earth platform built directly against the Gorgān Wall, that enclosed it to the north, and was surrounded by a moat filled with water, and fed by its own canal that took water from the Gorgān River to the south. It is possible (but not proved) that this moat was connected to the main moat of the Gorgān Wall and so that some (or perhaps all of the forts) acted like an integral part of the whole hydraulic system, helping to keep the water flowing along the main moat. It follows a rectangular plan with a total surface inside the walls of 5.50 ha. On the west, south and west sides it was surrounded by a defensive wall built of mudbricks as the Gorgān Wall and provided with projecting towers that projected 4.50 m in front of the wall, at intervals of 30 m. As with the main wall, it is impossible to know with any degree of certainty how tall the towers and the walls of the fort were; the surviving mounds for the towers measure about 3.70 m in height. The walkway of the wall and the top of the towers may have been paved with paved bricks to reduce the damage caused by winter rains, and the same may have been possible in the case of the parapet.

Inside the walls, there were eight long buildings distributed symmetrically, with two buildings by quadrant, with the long streets between them in the north-south direction being much wider than the narrow passageways in the west-east direction. Each of these buildings measured 116 m of length and was divided into 24 pairs of rooms (one room opening to each long “street” to its east and west) at ground level, for a total of 748 rooms at ground level. Archaeologists are almost sure that these buildings were military barracks, and that they had two floors, as the height of the surviving mudbrick walls is 3.30 m, far too high for a single height military building of this sort. This would mean that the total number of rooms (if they were indeed fully divided, and the upper space did not work as an attic) may have been as high as 1,496.

Map of the reconstituted track of the Gorgan Wall (its westernmost end is located in a saltwater lagoon heavily covered by sediments), the Gorgān River and the forts along it, which were numbered by the Survey. The arrows indicate the canals that brought water to the moat from the Gorgān River (image taken from “Persia’s imperial power in Late Antiquity. The Great Wall of Gorgān and frontier landscapes of Sasanian Iran”, edited by Eberhard W. Sauer, Hamid Omrani Rekavandi, Tony J. Wilkinson and Jebrael Nokandeh).

Reconstructed plan of Fort 4, showing the barracks and the canals that crossed the compound and the trenches dug during the excavation (image taken from “Persia’s imperial power in Late Antiquity. The Great Wall of Gorgān and frontier landscapes of Sasanian Iran”, edited by Eberhard W. Sauer, Hamid Omrani Rekavandi, Tony J. Wilkinson and Jebrael Nokandeh).

Not all these rooms may have been soldiers’ lodgments, as there would have been a need for storage space, as well as larger lodgments for officers. This has allowed for some rough estimates about the size of the fort’s garrison, using as a guide the well-studied Late Roman forts of El-Lejjūn (Israel) and Deutz (Divitia) in Germany, as well as the Late Roman or Sasanian fortress at Ain Sinu in northern Iraq. The researchers thought that the garrison must have been around 2,000 men (same as the garrison of El-Lejjūn between 300 and 363 CE, while Fort 4 is actually 120% of the size of the Roman fort). There is also the possibility that all or at least part of the garrison may have consisted of mounted soldiers, as the main north-south “corridors” onto which the rooms open are wide enough (21 m, and 34 m in the case of the central one) to keep horses tethered in front of the barracks, on both sides of the corridor. Incidentally, a number of 2,000 men would be the equivalent of two gunds (regiments), with each half of the fort, divided by the wider central corridor, lodging one gund.

The German historian Franz Altheim showed in the last century, based on an episode by Tabari concerning events in the 630s CE, that Sasanian soldiers in permanent garrisons lived with their wives and children. But the barracks seem quite cramped for this sort of coexistence, and inside the fort not a single “gendered” object attributable to women or children has been located. Instead, there are quite telling remnants of some sort of dispersed habitat outside the fort, that the surveyors think may have been where the families of the garrison lived in. Although no excavations were conducted there, the reasoning behind this is that Ammianus Marcellinus wrote that in the IV c. that Sasanian soldiers in garrisons were not paid in cash but in kind (only the field army was paid in cash), and that this is possibly also applicable to the Sasanian garrisons of the V-VII c. CE. This is reinforced by the fact that no coins at all have been found in the fort. The lack of cash would have meant that these forts might not have attracted traders and so that commercial settlements that the ones that appeared next to legionary encampments during the High Empire might not have formed in this case. This leaves the families of the soldiers as the only plausible reason for the existence of such settlements.

Satellite image of Fort 4; notice the canal that brought water to the fort on its southern corner (image taken from “Persia’s imperial power in Late Antiquity. The Great Wall of Gorgān and frontier landscapes of Sasanian Iran”, edited by Eberhard W. Sauer, Hamid Omrani Rekavandi, Tony J. Wilkinson and Jebrael Nokandeh).

The main “irregularity” in the outlay of the Wall is the inclusion of the hill/mound known as Qīzlar Qal’eh within the defenses. This is a 16-meter-high mound located 200-400 meters north of the wall, and it was a potentially weak point of the defense, as from its top it would have been possible to oversee the troop movements happening behind the wall. Two wall sections protrude from the main wall at this point at a 90º angle and run all the way to Qīzlar Qal’eh, surrounding all its base in a “loop-shaped” extension. Qīzlar Qal’eh itself is part of a much larger site, called Qārniāreq Qal’eh, which extends well to the south and west of the “loop” The occupation of this larger site may have lasted from prehistory to Arsacid or Sasanian times. If it was still in inhabited when the Great Wall of Gorgān was built, then it must have been evacuated, as the “loop” cuts right across the sight. Due to its singularity, it was submitted to a more detailed survey.

It is possible that Qīzlar Qal’eh may have been the citadel of the larger site. It was itself surrounded by a 2.20-meter-wide mudbrick wall, while the mount was surrounded at the base by the “loop” built with the same fired bricks as the rest of the Gorgān Wall. The moat in front of the main wall also followed the track of the loop, enveloping the Qal’eh on three sides. The awkwardness of the whole design has made archaeologists think that its inclusion within the defensive system was probably an afterthought. The Qal’eh may also have acted as another fort along the Wall, as it is located between Forts 29 and 30, which are separated by a distance of 9.70 km, greater that between any two other forts.

Heavily eroded remains of the canal that brought water to Fort 4 (image taken from “Persia’s imperial power in Late Antiquity. The Great Wall of Gorgān and frontier landscapes of Sasanian Iran”, edited by Eberhard W. Sauer, Hamid Omrani Rekavandi, Tony J. Wilkinson and Jebrael Nokandeh).

Given the results of the Survey, the archaeological team ventured into an estimate of the permanent garrison of the Great Wall of Gorgān. Although they did not explore all the forts, the CORONA images clearly show that although not all the forts were of the same size as Fort 4, all of them had remains of barracks in their interior. The more plausible size of the garrison estimate was 30,000 men (between a minimum of 15,000 and a maximum of 45,000). In order to further test the plausibility of this estimate, they compared it to the well-studied case of Hadrian’s Wall in Britain. If the same density of soldiers per kilometer that existed there were to be applied in the case of Gorgān, we would obtain a result of 26,000 men, which the archaeological team considered close enough to their estimate. In their opinion, the higher number of 30,000 men would be more credible if we account for the fact that the enemy north of the Gorgān Wall was much more dangerous than the one across Hadrian’s Wall.

The surveyors also noticed that the larger forts were concentrated on the eastern part of the Wall, and they concluded that this was probably due to the fact that terrain is more irregular in this part of its trace, where there are several valleys that the Wall has to cross, and which are potentially weak points. Also, if the Sasanian city of Gorgān was located at Gonbad-e Kāvūs or at the nearby site of Dašt Qal’eh, then the large Forts 10, 12 and 13 would have provided added protection to it.

The westernmost end of the Wall is the most damaged part, and the visible remains (visually or by CORONA images) disappear some km before reaching the actual coastline. Given that the water level of the Caspian Sea was then lower than in contemporary times, a part of the Wall might be laying submerged under the waters, north of the medieval port of Ābeskūn, which according to the surveyors was probably also in existence during the Sasanian era. There is a possibility that the forts laying under the waters there may also have been of the larger sort, in order to prevent the possibility of a flanking attack that tried to outflank the Wall with boats.

The Tammīšeh Wall was built further to the west, on a north-south axis from the northern slopes of the Ālborz Mountains to the southern shore of the Caspian Sea. It receives its name from the nearby town of Tammīšeh, located immediately to the east of the Wall. Traveling west to east along the southern Caspian shoreline, the distance between the Alborz Mountains and the shore diminishes, so the location of the Wall is the most convenient one, as in this point the coastal plan has been reduced to a narrow corridor. It is slightly oriented on a N-NW axis because of the presence of a nearby river valley. In 1964, A. H. D. Bivar and G. Fehérvári were able to conduct excavations in this area before modern agricultural machinery was able to have much of an impact, and this helped immensely the survey, because in the 40 years in between the landscape has changed considerably. The fertile land and the humid climate make this one of the most productive agrarian landscapes in Iran, and the place has been heavily disturbed. On top of it, the bricks of the Wall have been robbed even more intensely than at Gorgān, and the humid climate has damaged remains other than brick or stone in a much more extensive way.

CORONA image of the northern terminal of the Tammīšeh Wall, with the remains of a fort submerged in an area of shallow water in the Caspian Sea (image taken from “Persia’s imperial power in Late Antiquity. The Great Wall of Gorgān and frontier landscapes of Sasanian Iran”, edited by Eberhard W. Sauer, Hamid Omrani Rekavandi, Tony J. Wilkinson and Jebrael Nokandeh).

The extension of the damage is such that archaeologists do not even know how wide it might have been. XIX c. travelers wrote that to them the wall looked like a succession of three ditches, but today the only remnants are a ditch and a land embankment to the east of it, suggesting that (contra intuitively) the ”enemy” side of the Wall was the western one, where the wide ditch might have acted like a moat. The embankment was 5.60-5.10 meters wide at the base, and 1.00-3.00 meters high, and 2.00-2.25 meters wide at the top. The surveyors think (although with a considerable degree of uncertainty) that this earthwork was probably flanked on both sides by walls of fired brick to protect it from erosion (given the rainy climate), and that it acted as a foundation for the Wall proper, which would have been built on top of it. This relies of the results from Bivar and Fehérvári’s 1964 dig: by chance, they found at the southern end of the Tammīšeh Wall the remains of a brick wall and a projecting tower of semi-elliptical plan built on top of the embankment. Due to the lack of remains elsewhere, this is the only real inkling at what the actual wall could have been like in Sasanian times.

Some more guesses can be made from comparisons with other Sasanian defensive walls. At the Darband wall (made of stone), the interval between the towers is of ca. 3.00-4.00 km. At the Ghilghilchay Wall (which is 50 km long in total, and made of mudbrick), the projecting towers are placed at variable 29-49 m intervals, with smaller projecting semi-circular protrusions that acted as buttresses located every 7.00-7.30 m; the wall was 4.10 m thick and the buttresses projected 5.20 m from its faces, on both sides. This can also serve as a guide for the Gorgān Wall, where few projecting towers have been found too.

The Tammīšeh Wall was built with fired bricks remarkably similar to the ones used in the Gorgān Wall (only slightly smaller, 38x38 cm instead of 40x40 cm), and actually these bricks are identical to the ones employed in the westernmost parts of the Gorgān wall. This suggests that both walls were built at the same time, and that probably the same teams that worked at the Tammīšeh Wall worked also in the western part of the Gorgān Wall. The construction of the Tammīšeh Wall was not uniform; in its southern part the wall climbs up a deep slope when it meets the Ālborz Mountains for a while before reaching its end. Here, building the earthwork as a foundation would not have been practical, but the moat was remained in front of the wall. When the Wall ends, it is followed by an earth bank that the surveyors believe may have been the aqueduct that fed the moat with water The survey team thought that as for the height of the wall, the earthwork at its base would have been 2.80 meters high at the very least and 4.00 m high maximum. As for the possible height of the upper wall, that is not possible to ascertain in situ due to the systematic robbing of its bricks. The only guess that can be made is again through comparison with other Sasanian walls, or through the accounts of XIX c. travelers or earlier Islamic accounts.

Still today, the parts still standing of the Darband Wall reach a height of 6 meters. In a report from 1580, the two parallel walls at Darband that go from the city to the sea would have been still 9 feet thick and 28-30 feet tall (i.e. 9.00 meters). Another report from 1770 stated that the walls still stood to a height of 9 meters. Another report of the XIX c. gives a height of 8-9.00 meters. This seems to be in agreement with the volume of the piles of rubble detected by Russian archaeologists under the Caspian Sea in the submerged part of the Darband wall. The current wall at Darband was built in the VI c. CE to replace an earlier one built of mudbrick between 439 and 450 CE, and which according to the descriptions of the ancients sources had a width of 8.00 m and a height of up to 16.00 m. The better-preserved parts of the Ghilghilchay Wall stand today to a height of 6.00-7.00 m. As an additional comparison, the earthen walls built in China during the IV c. CE survive to a height of 18 m. To the archaeologists of the GWS, it seems unlikely that the Gorgān Wall, built without foundations and without lime mortar, may have been higher than the Darband Wall, but the Tammīšeh Wall may have been higher.

Then there is the added matter of the submerged parts of both walls, and the possibility that they may have been joined back in the day of their construction due to the lower water level of the Caspian Sea. Underwater research under the Caspian in this area was complicated due to the murkiness of the water, but archaeologists were able to confirm the presence of a submerged fort under shallow waters where the Tammīšeh Wall reaches the current coastline, and that this Wall continues 700 meters following its same N-NW axis under the sea.

Old house at the village of Sarkālateh whose foundations have been built with bricks from the Tammīšeh Wall (image taken from “Persia’s imperial power in Late Antiquity. The Great Wall of Gorgān and frontier landscapes of Sasanian Iran”, edited by Eberhard W. Sauer, Hamid Omrani Rekavandi, Tony J. Wilkinson and Jebrael Nokandeh).

But there was less luck in the case of the Gorgān Wall. Nowadays, traces of the Wall disappear in what is now a shallow water lagoon, and the in area where it supposedly should have entered the Caspian Sea the bottom of the sea is completely silted up by sediments of the Gorgān River, which anciently used to meet the Caspian a bit to the south from here. According to a XIX c. traveler, he could observe that the wall ran to the south along the coast to the mouth of the Qarah Sū stream, which is located southern than the current mouth of the Gorgān River, but the survey was unable to verify these claims. From the mouth of the Qarah Sū current to the current end of the Tammīšeh Wall there is only a distance of 2.4 km, but the fact that the underwater survey detected that said Wall is prolonged 700 m to the N-NW under the current water level makes any possibility of both walls joining according to this XIX c. report quite implausible.

Other than the submerged fort at the Caspian shore, only another fort has been detected along the Tammīšeh Wall, at its southern terminal, where the Wall starts its climb of the steep slopes of the Ālborz Mountains. This is the Bānsarān Fort (Qal’eh-ye Bānsarān). It is actually located 500-700 meters east of the Wall, and the archaeological team though this was probably done so that its garrison would be better positioned to intercept any attempt at outflanking the Wall through the mountains. At this point, the surveyors also noted that the town of Tammīšeh itself was known as a strongly fortified town in the early Islamic era, and is already attested by Ṭabarī to have been in existence in 650-651 CE, and so that in Sasanian times it may also have had a strong garrison.

Bānsarān Fort is somewhat shrouded in legend. According to Ferdowsī, the legendary King Fāridūn resided here, and the same tale is repeated by Ibn Isfandīyār. It covers a surface of 5 ha. and it was built on a distinct raised platform. It was surrounded by a defensive wall built exactly like the main Tammīšeh Wall. The excavations inside the precinct though provided a different result than at Fort 4. Mudbricks were of no use here due to the rainy climate, so probably wood was the main construction material. Many ceramic tiles were also found scattered around the site, which perhaps formed the roofs of the buildings. Also, at the center of the compound the excavators found the remains of a large three-aisle building with a monumental façade, all built in fired brick. They were unsure about its use or chronology; it could even be an early Islamic mosque; the bricks were of a different, smaller size than the bricks used to build the Wall, so archaeologists suspect that this building was built during a later stage. Given the amount of rubble generated by its collapse, the building might have been of substantial height, and certainly the higher one within the fort.

Remains of one of the excavated kilns that were used to make the fired bricks for the Gorgān Wall (image taken from “Persia’s imperial power in Late Antiquity. The Great Wall of Gorgān and frontier landscapes of Sasanian Iran”, edited by Eberhard W. Sauer, Hamid Omrani Rekavandi, Tony J. Wilkinson and Jebrael Nokandeh).

As for garrison estimates, the surveying team gave an amount of 2,000 men at Bāndirān Fort and 500 men at the submerged fort. There may also have been more forts further north (under water now) and as I wrote above, it is quite possible that the town of Tammīšeh was also garrisoned, with its prominent citadel. As we will see later in more detail, the plan of the old town strongly resembles that of one of the “campaign bases” at the Gorgān Plain: rectangular with a citadel on a corner, like the great encampment of Qal’eh Ḵarābeh. If this was indeed its origins, then in Sasanian times, with a surface of ca. 20 ha. (about half of that of Qal’eh Ḵarābeh) could have quartered up to 5,000 cavalrymen.

There are also some mountain refuges and forts scattered around the mountains to the south of the end of the Tammīšeh Wall (the refuges being clearly intended as a hiding for the civilian population in troubled times), but their chronology is unclear; it is possible that all of them were built during the early Islamic era.

I have mentioned the Great Wall of Gorgān repeatedly in previous posts, but deliberately I have withheld any further comment on the subject because I thought that it deserved to be explained and explored in length and not in a passing commentary. Located in what is today Golestān Province in northern Iran, it is the second longest continuous wall in the Late Ancient world after the Great Wall of China, and it extended along 195 km from the westernmost slopes of the Ālādāgh Range (which is itself a western offshoot of the larger Koppeh Dagh Range that separates the Iranian Plateau to the South from the Turanian Basin to the north) along the valley of the Gorgān River, until reaching the shore of the Caspian Sea. The wall itself was 6-10 m wide, with over 30 fortresses at intervals of between 10 and 50 km, and with a substantial moat than ran parallel to the wall on its northern side and was filled with water of the Gorgān River. A substantial part to the west appears to be buried under marine sediments under the Caspian Sea (it is supposed that the water level of the Caspian was lower back in Sasanian times, as something similar has been noticed at the Darband Wall). It could even be linked up undersea with the similar Tammīšeh Wall, another linear barrier of similar design and built with the same type of bricks built to its west, closing the Caspian lowlands as a north-south barrier, from the Caspian shore to the Ālborz Mountains.

Satellite view of the southern Caspian Sea Shore, looking west. The widening green plain in the lower right corner is the Gorgān Plain, and the mountain chain in the center of the picture is the Ālborz Range, which separates the lowlands of the Caspian Sea from the Iranian Plateau to the south (left in the picture).

Nowadays, practically nothing remains of it at ground level, as most of the wall was made with fired bricks that were systematically looted by the local population across the centuries. The wall also runs through fertile agricultural flatlands, and many sections have been tilled over repeatedly over the centuries. But despite all these factors, it is still visible by the naked eye in the landscape, as the limits of land plots tend to follow its course, and the massive moat in front of it has not been filled in most places. Its trace becomes even more obvious and visible from the air and on satellite images, where it forms a very visible feature of the landscape. In Iranian lore, it has usually been referred to as “Alexander’s Wall”, as the Macedonian conqueror was described as a wall builder in the Qur’an and the Šāh-nāma, and also (less often) as “Anuširwān’s Wall” (after the Sasanian king Xusrō I) or “Pērōz’s Wall”, while the local Turkmen population called it “The Red Snake” (Qizil Alan, due to the red color of its fired bricks). It was abandoned sometime during the first half of the VII c. CE, as the Sasanian Empire became embroiled in its last great war against the Romans which was followed by its disintegration and the Muslim conquest soon thereafter.

The valley of the Gorgān River is (as I have said before) a fertile, well-watered and easy to cultivate area, and so it has been inhabited by agriculturalists since the Neolithic. Historically, it has been part that the region known by Classical geographers as Hyrcania, which also included the southern shore of the Caspian Sea to an undetermined limit to the west. It formed a satrapy under the Achaemenids, with its capital at Zadrakarta (located at the site called Qal’eh-ye Ḵandān or perhaps at the modern city of Gorgān. Confusingly, the Sasanian city of Gorgān does not coincide with the modern city of the same name (which was known as Astarābād before the mid-XX c.) but corresponds either to the modern town of Gonbad-e Kāvūs, located directly by the Gorgān River, or to the nearby Sasanian ruins at the site known as Dašt Qal’eh.

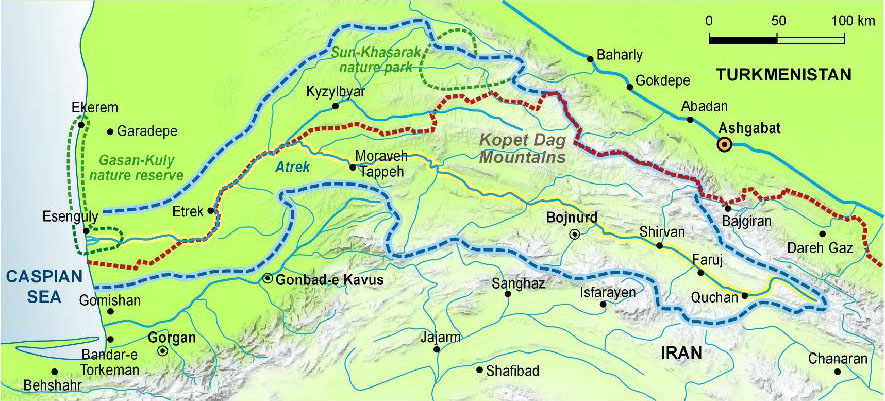

Properly speaking, the Gorgān Plain is the name of the flat land that stretches from the southern bank of the Gorgān River to the foothills of the Ālborz Mountains. The flat land continues across the Gorgān River, but it is usually called Gorgān Steppe here, as far as the southern bank of the Ātrak River, that runs roughly parallel to the Gorgān River to its south and in this part of the country acts as the border limit between the Islamic Republic of Iran and the Republic of Turkmenistan. North of the Ātrak, the steppe becomes dryer until it turns into the Karakum Desert all the way to the lower course of the Āmu Daryā and the Ustyurt Plateau to the north. The soil of the Gorgān Plain and Steppe is formed by fine loess deposited there after the glaciations of the Pleistocene, and is very prone to erosion; due to this all the rivers have ended up excavating relatively deep riverbeds through it, non-paved and human pathways usually end up becoming trenches (which has eased greatly the task for archaeologists and researchers when trying to reconstruct the ancient settlement patterns of this area).

The different climate and settlement areas in the Gorgān region (image taken from “Persia’s imperial power in Late Antiquity. The Great Wall of Gorgān and frontier landscapes of Sasanian Iran”, edited by Eberhard W. Sauer, Hamid Omrani Rekavandi, Tony J. Wilkinson and Jebrael Nokandeh).

The amount of rain received by the land decreases sharply following a south-north gradient, with the Gorgān River roughly being the limit between the lands where sedentary agriculturalists are attested, while settlement in the steppe to the north of the river has been more sporadic and dictated by climate changes and political circumstances. In the Sasanian era, the Caspian Sea underwent a regression event (known as the Derbent or Darband Regression) and its level was quite lower than it is today; this marked probably its lowest level between the two maximum reached around 500 BCE and the XIV-XV c. CE. Due to this, the western part of the steppe, closer to the Caspian seashore, displays several saline flatlands where only vegetation adapted to salt-ridden soils can grow, and where agriculture is not possible. The movements of the Caspian seashore also have left other marks on the landscape, like sand dunes and small cliffs where the ancient seashore used to be. Apart from the main south-north rain gradient, there is also an east-west gradient, with the eastern part of the Gorgān Steppe receiving more rainwater than the western part.

In 2007, Iranian and British archaeologists began the Gorgān Wall Survey (GWS), on which our current state of knowledge of the Great Wall of Gorgān and its environment rests. Previously, the Iranian archaeologist Mohammad Kiani had conducted an important field research which included the drawing of an excellent and very accurate set of maps of the area, but GWS employed satellite images, mainly from the CORONA satellite system taken in the 1960s and that were declassified in the 2000s as well as other satellite systems, and which offered excellent aerial pictures of very great resolution before the great changes to the landscape suffered since then by the increases in population density, the extension of irrigation networks and the deployment of heavy machinery for agrarian improvements. The results of the GWS were later published in a book, Persia’s imperial power in Late Antiquity. The Great Wall of Gorgān and frontier landscapes of Sasanian Iran, edited by Eberhard W. Sauer, Hamid Omrani Rekavandi, Tony J. Wilkinson and Jebrael Nokandeh, and published by Oxbow Books. Most of the information and maps that displayed in this chapter come from this book.

The results of the survey show that the settlement north of the Gorgān River peaked in the Late Iron Age (ending with the Achaemenid era) and concentrated (as was to be expected) on the eastern part, which receives more rainfall. Archaeologists though are unsure if these settlements should be ascribed to active colonizing policies encouraged by the Median and Achaemenid Empires or to spontaneous settlement of nomadic populations, a pattern well attested historically in Iran and the Middle East. Settlement also peaked on the western part of the steppe, but at a lower density, and thanks to the building of two large irrigation canals that drew water from the Gorgān River. The river itself has also shifted course repeatedly during historical times in its lower course, as this is a seismically active area, and several of these ancient riverbeds were identified during the survey.

Another satellite image, with the position of the modern city of Gonbad-e-Kāvūs on the Gorgān River. The Alborz Mountains merge to its southeast with the Ālādāgh Range that then runs on a southeast course forming the northern limit of Khorasan. The Koppeh Dagh Range runs parallel to the Ālādāgh Range to its north, and the upper valley of the Ātrak River separates both mountain chains. The region to the north of Gorgān and to the west of these mountains is Dihistān.

Gorgān and the steppe region immediately north to it (Dihistān) were the home of the Aparni tribe of the Saka tribal confederation, a group of which eventually moved south crossing the Alborz Range and settling in the Seleucid satrapy of Parthia in the III c. CE under the leadership of Aršak. The first Arsacid capital, know to archaeologist as Old Nisa (ancient Mithradatkert) was located to the east of the Gorgān Steppe, on the foothills of the Koppeh Dagh (today in southern Turkmenistan, very near the Iranian border), and some modern scholars have related the depopulation of the steppe north of the Gorgān River to the displacement of the Arsacid capital to Hekatompylos (its remains are located at Šāhr-e Qūmes to the west of Dāmḡān) in Parthia proper further to the south in the Iranian Plateau.

But the survey has revealed that at the time of the construction of the wall, the steppe north of the Gorgān River was mostly uninhabited or very scarcely settled, despite the finding of administrative bullae and the writings of X c. CE Islamic geographers that attest to the existence of Sasanian/Iranian settlements in Dihistān, the survey has failed to locate substantial traces of them between the Gorgān and Ātrak rivers during the V-VI c. CE. Thus, even if the Sasanian kings claimed their rule over territories located to the north of the Gorgān River, the lands cultivated by sedentary agriculturalists ended at this river, that acted at the time as a sort of border between the sedentary and nomadic worlds. There were also two other important factors that probably influenced the decision to have it built in this location: this is the pace the place where the Ālādāgh Mountains are closer to the Caspian Sea, and where the Gorgān River helped with the building process and also offered an easy way to supply the garrison of the wall with water.

During the survey, the archaeologists discovered that the trace of the wall was mainly influenced by hydraulic considerations, i.e. that the wide moat (actually a proper canal) that ran in front of the wall kept enough of a gradient to channel the water to the Caspian in a controlled way. In this, the Great Wall of Gorgān actually resembles more in its conception the linear water defenses of Mesopotamia (like the “Ditch of Šābuhr” built by Šābuhr II to protect Āsūrestān against A’rab raids on the western bank of the Euphrates) than to other linear barriers like the Darband Wall, the Wall of Hadrian or the Great Wall of China. The trace of the wall was thus determined by the trace of the canal/moat/ditch in front of it, and three connecting canals were built carrying water from the upper course of the Gorgān River to feed it. these canals had to cross river valleys in some cases (of the tributaries of the Gorgān River in its upper course), so aqueducts had to be built to keep an optimum hydraulic gradient. The survey determined that the eastern end of the wall was prolonged 15 km into the Ālādāgh Mountains, and ends in a heavily wooded region, against a steep rock cliff, atop of which the remains of a Sasanian building (probably a fort) were detected. In this part of its trace, the terrain is too steep for a moat, so the wall actually runs south of the Gorgān River, that acts as a natural moat in front of it.

Before entering the plain, the wall crosses over the Gorgān River and then continues its trace all the way to the Caspian seashore to the north of the river. Nowadays, the lower course of the Gorgān River deviates to the southwest after passing the town of Gonbad-e Kāvūs, but in Sasanian times the riverbed followed closely the trace of the wall, quite further north. In the 1930s, the American geologist Lester Thompson noted that along the entire trace of the wall across the plain, the moat formed a continuous ditch of 8-9 m. wide and 2 m. deep. The land displaced in order to dig the moat was used to erect a large linear earthwork that was located directly behind the wall, and to manufacture the fired bricks the made was built with. Due to the lack of wood or stone in the plain, the wall had to be built with bricks, but unlike in Mesopotamia, mudbricks could not be used as they would have lasted only a few years under the winter rains in this environment, so fired bricks were the only alternative. As they had to be produced as near to the building place as possible, thousands of kilns were built (which were located during the survey) along the wall to produce the 100-200 million bricks necessary for the construction of the wall. The canal/moat provided the water necessary and perhaps also allowed for the transportation of supplies for the kilns and the building crews. The result of this is that until the recent massive disruption of the site in the latest decades, the remains of the wall actually resembled three parallel obstacles: the outer embankment, the moat/canal bed, and the inner embankment on which the wall was built. And as a last line of defense, the Gorgān River followed closely the trace of the wall to its south (which became a further ditch after the lower course of the river moved).

Map of the Gorgān Plain showing the ancient riverbeds of the Gorgān River and the old irrigation channels dated to the Bronze Era that had been long abandoned when the Wall was built (image taken from “Persia’s imperial power in Late Antiquity. The Great Wall of Gorgān and frontier landscapes of Sasanian Iran”, edited by Eberhard W. Sauer, Hamid Omrani Rekavandi, Tony J. Wilkinson and Jebrael Nokandeh).

The bricks were all produced following exactly the same pattern: square in plan (40x40 cm, approx.) and 7-8.5 cm. high. The fact that the wall was built with fired bricks in a landscape that is otherwise barren of building materials has been the main reason for the poor state of preservation of the wall: for centuries, the local population robbed the bricks for other uses, until only the foundations were left. In the eastern section of the wall, the best-preserved section found by the section contained thirteen courses of bricks, to a total height of 1.47 m. In all the excavated trenches, the wall proved to be five bricks wide (2 m). In the plain, this 2 meters-thick wall was then abutted on its southern side by a large earthwork made with the earth extracted from the moat’s ditch that had not been used for making the bricks of the wall. Obviously, once the wall entered the rocky landscape of the Ālādāgh, where there was no moat, this earthwork behind the wall is also absent. The collapse of this earthworks northwards as the wall was robbed from its bricks is what has allowed the lower courses of bricks in the lower parts of the wall to survive.

Due to this robbing out process, archaeologists have no way of knowing for sure how tall the wall might have been, although they consider that it may have been quite similar in this respect to the (better preserved) Tammīšeh Wall further west. All sections of the wall (even in the Ālādāgh Mountains) were built using the same type of fired brick, and with no bonding other than mud. Archaeologists also have no clue about how the parapet of the wall might have looked like, or even if it existed at all. In the plain section, where there is the earthwork behind the wall, archaeologists have suggested that this earthwork could have been paved on its top with fired bricks and acted as a communications road behind the wall, either at the same height of the parapet, or slightly under it. That would explain the obvious absence of a road along the wall on its southern sider, as it was common in the Roman border walls, and as it would have been necessary in order to allow the garrisons to displace themselves quickly to any spot under menace. Due to the light loess soil in the area, even if such a road had been unpaved, it would have quickly become a ditch and it would have left visible traces in the landscape.

Easternmost track of the Gorgān Wall, showing how it changed course from being north to south of the Gorgān River (image taken from “Persia’s imperial power in Late Antiquity. The Great Wall of Gorgān and frontier landscapes of Sasanian Iran”, edited by Eberhard W. Sauer, Hamid Omrani Rekavandi, Tony J. Wilkinson and Jebrael Nokandeh).

East of the Pīš Kamar Rocks, where the wall leaves the plain, the earth bank at the bank of the wall disappears, even though there is still a dry moat in front of it, which also disappears in front of it. Archaeologists think that in this part of the wall, the top of the wall must have been three or four bricks wide at the top (1.20-1.60 m), far too narrow to allow for a parapet or a walkway, and think that some sort of wooden scaffolding behind the wall might have been a possibility. And there is still a further possibility to be considered: that the wall lacked indeed any parapet or walkway and that it acted just as a demarcation line. In this respect, it is worth nothing that the survey unable to elucidate if there were interval towers along the wall. CORONA satellite images from the 1960s seem to show small mounds adjacent to the wall, near Fort 8, but these remains are still unexcavated. Archaeologists though warn that towers, especially if they were built on an elevated earthwork base, could have been robbed out of bricks all the way to their foundations, which would make them difficult to detect. Only one interval tower was located by the archaeologist J. Nokandeh, and the survey was able to locate another one later at the Tammīšeh Wall.

The conclusion of the members of the survey was that the wall had not been designed to be an insurmountable obstacle in itself, but that its purpose was to bring small-scale raiding to a halt and to turn any large-scale attacks into dangerous and difficult enterprises. Given that any attackers from the north would have been a cavalry army, and possibly nomads (although this conclusion of the surveyors does not really apply to the Hephthalites, who were far from being “real” nomads), even if they managed to climb the wall, they could not bring their horses with them, and any attack that would have wanted to breach the wall would have needed the use of siege machines like rams, difficult to use given the wide and deep moat and the fact that the wall was well cushioned by the earth mound on its back. Mining would also have been easily detected by the defenders in the flat and bare landscape of the steppe, and the nature of the loess soil would have made the mining in itself quite risky. In short, breaching the wall would have needed the attack of a large army, with the establishment of large-scale siege operations, that conceivably would have given the Sasanian defenders time to react and prepare countermeasures.

But rather than simply its design or construction, the real interest of the Gorgān Plain Survey lies in the fact that it has shed new light onto the organization and numbers of the Sasanian army of the V c. CE, and as a consequence, on the very nature of the Sasanian state itself. Over thirty forts separated about 5-6 km from each other, have been detected along the wall through satellite images, of which Fort 4 was chosen to conduct a more thorough archaeological study.

Remains of two of the canals that fed the moat of the Gorgān Wall (image taken from “Persia’s imperial power in Late Antiquity. The Great Wall of Gorgān and frontier landscapes of Sasanian Iran”, edited by Eberhard W. Sauer, Hamid Omrani Rekavandi, Tony J. Wilkinson and Jebrael Nokandeh).

The reason for this choice was the mound of this fort was the best preserved along the wall, probably due to the existence of a small burial ground on its top, which had caused it to be left undisturbed. As a contrast, Forts 28 and 33, which are perfectly visible on the CORONA images, had been completely flattened by the time the survey took place. The forts along the wall in the plain followed a standard plan, of which Fort 4 is a representative example, although not all of them were of the same size.

Fort 4 was built on a raised earth platform built directly against the Gorgān Wall, that enclosed it to the north, and was surrounded by a moat filled with water, and fed by its own canal that took water from the Gorgān River to the south. It is possible (but not proved) that this moat was connected to the main moat of the Gorgān Wall and so that some (or perhaps all of the forts) acted like an integral part of the whole hydraulic system, helping to keep the water flowing along the main moat. It follows a rectangular plan with a total surface inside the walls of 5.50 ha. On the west, south and west sides it was surrounded by a defensive wall built of mudbricks as the Gorgān Wall and provided with projecting towers that projected 4.50 m in front of the wall, at intervals of 30 m. As with the main wall, it is impossible to know with any degree of certainty how tall the towers and the walls of the fort were; the surviving mounds for the towers measure about 3.70 m in height. The walkway of the wall and the top of the towers may have been paved with paved bricks to reduce the damage caused by winter rains, and the same may have been possible in the case of the parapet.

Inside the walls, there were eight long buildings distributed symmetrically, with two buildings by quadrant, with the long streets between them in the north-south direction being much wider than the narrow passageways in the west-east direction. Each of these buildings measured 116 m of length and was divided into 24 pairs of rooms (one room opening to each long “street” to its east and west) at ground level, for a total of 748 rooms at ground level. Archaeologists are almost sure that these buildings were military barracks, and that they had two floors, as the height of the surviving mudbrick walls is 3.30 m, far too high for a single height military building of this sort. This would mean that the total number of rooms (if they were indeed fully divided, and the upper space did not work as an attic) may have been as high as 1,496.

Map of the reconstituted track of the Gorgan Wall (its westernmost end is located in a saltwater lagoon heavily covered by sediments), the Gorgān River and the forts along it, which were numbered by the Survey. The arrows indicate the canals that brought water to the moat from the Gorgān River (image taken from “Persia’s imperial power in Late Antiquity. The Great Wall of Gorgān and frontier landscapes of Sasanian Iran”, edited by Eberhard W. Sauer, Hamid Omrani Rekavandi, Tony J. Wilkinson and Jebrael Nokandeh).

Reconstructed plan of Fort 4, showing the barracks and the canals that crossed the compound and the trenches dug during the excavation (image taken from “Persia’s imperial power in Late Antiquity. The Great Wall of Gorgān and frontier landscapes of Sasanian Iran”, edited by Eberhard W. Sauer, Hamid Omrani Rekavandi, Tony J. Wilkinson and Jebrael Nokandeh).

Not all these rooms may have been soldiers’ lodgments, as there would have been a need for storage space, as well as larger lodgments for officers. This has allowed for some rough estimates about the size of the fort’s garrison, using as a guide the well-studied Late Roman forts of El-Lejjūn (Israel) and Deutz (Divitia) in Germany, as well as the Late Roman or Sasanian fortress at Ain Sinu in northern Iraq. The researchers thought that the garrison must have been around 2,000 men (same as the garrison of El-Lejjūn between 300 and 363 CE, while Fort 4 is actually 120% of the size of the Roman fort). There is also the possibility that all or at least part of the garrison may have consisted of mounted soldiers, as the main north-south “corridors” onto which the rooms open are wide enough (21 m, and 34 m in the case of the central one) to keep horses tethered in front of the barracks, on both sides of the corridor. Incidentally, a number of 2,000 men would be the equivalent of two gunds (regiments), with each half of the fort, divided by the wider central corridor, lodging one gund.

The German historian Franz Altheim showed in the last century, based on an episode by Tabari concerning events in the 630s CE, that Sasanian soldiers in permanent garrisons lived with their wives and children. But the barracks seem quite cramped for this sort of coexistence, and inside the fort not a single “gendered” object attributable to women or children has been located. Instead, there are quite telling remnants of some sort of dispersed habitat outside the fort, that the surveyors think may have been where the families of the garrison lived in. Although no excavations were conducted there, the reasoning behind this is that Ammianus Marcellinus wrote that in the IV c. that Sasanian soldiers in garrisons were not paid in cash but in kind (only the field army was paid in cash), and that this is possibly also applicable to the Sasanian garrisons of the V-VII c. CE. This is reinforced by the fact that no coins at all have been found in the fort. The lack of cash would have meant that these forts might not have attracted traders and so that commercial settlements that the ones that appeared next to legionary encampments during the High Empire might not have formed in this case. This leaves the families of the soldiers as the only plausible reason for the existence of such settlements.

Satellite image of Fort 4; notice the canal that brought water to the fort on its southern corner (image taken from “Persia’s imperial power in Late Antiquity. The Great Wall of Gorgān and frontier landscapes of Sasanian Iran”, edited by Eberhard W. Sauer, Hamid Omrani Rekavandi, Tony J. Wilkinson and Jebrael Nokandeh).

The main “irregularity” in the outlay of the Wall is the inclusion of the hill/mound known as Qīzlar Qal’eh within the defenses. This is a 16-meter-high mound located 200-400 meters north of the wall, and it was a potentially weak point of the defense, as from its top it would have been possible to oversee the troop movements happening behind the wall. Two wall sections protrude from the main wall at this point at a 90º angle and run all the way to Qīzlar Qal’eh, surrounding all its base in a “loop-shaped” extension. Qīzlar Qal’eh itself is part of a much larger site, called Qārniāreq Qal’eh, which extends well to the south and west of the “loop” The occupation of this larger site may have lasted from prehistory to Arsacid or Sasanian times. If it was still in inhabited when the Great Wall of Gorgān was built, then it must have been evacuated, as the “loop” cuts right across the sight. Due to its singularity, it was submitted to a more detailed survey.

It is possible that Qīzlar Qal’eh may have been the citadel of the larger site. It was itself surrounded by a 2.20-meter-wide mudbrick wall, while the mount was surrounded at the base by the “loop” built with the same fired bricks as the rest of the Gorgān Wall. The moat in front of the main wall also followed the track of the loop, enveloping the Qal’eh on three sides. The awkwardness of the whole design has made archaeologists think that its inclusion within the defensive system was probably an afterthought. The Qal’eh may also have acted as another fort along the Wall, as it is located between Forts 29 and 30, which are separated by a distance of 9.70 km, greater that between any two other forts.

Heavily eroded remains of the canal that brought water to Fort 4 (image taken from “Persia’s imperial power in Late Antiquity. The Great Wall of Gorgān and frontier landscapes of Sasanian Iran”, edited by Eberhard W. Sauer, Hamid Omrani Rekavandi, Tony J. Wilkinson and Jebrael Nokandeh).

Given the results of the Survey, the archaeological team ventured into an estimate of the permanent garrison of the Great Wall of Gorgān. Although they did not explore all the forts, the CORONA images clearly show that although not all the forts were of the same size as Fort 4, all of them had remains of barracks in their interior. The more plausible size of the garrison estimate was 30,000 men (between a minimum of 15,000 and a maximum of 45,000). In order to further test the plausibility of this estimate, they compared it to the well-studied case of Hadrian’s Wall in Britain. If the same density of soldiers per kilometer that existed there were to be applied in the case of Gorgān, we would obtain a result of 26,000 men, which the archaeological team considered close enough to their estimate. In their opinion, the higher number of 30,000 men would be more credible if we account for the fact that the enemy north of the Gorgān Wall was much more dangerous than the one across Hadrian’s Wall.

The surveyors also noticed that the larger forts were concentrated on the eastern part of the Wall, and they concluded that this was probably due to the fact that terrain is more irregular in this part of its trace, where there are several valleys that the Wall has to cross, and which are potentially weak points. Also, if the Sasanian city of Gorgān was located at Gonbad-e Kāvūs or at the nearby site of Dašt Qal’eh, then the large Forts 10, 12 and 13 would have provided added protection to it.

The westernmost end of the Wall is the most damaged part, and the visible remains (visually or by CORONA images) disappear some km before reaching the actual coastline. Given that the water level of the Caspian Sea was then lower than in contemporary times, a part of the Wall might be laying submerged under the waters, north of the medieval port of Ābeskūn, which according to the surveyors was probably also in existence during the Sasanian era. There is a possibility that the forts laying under the waters there may also have been of the larger sort, in order to prevent the possibility of a flanking attack that tried to outflank the Wall with boats.

The Tammīšeh Wall was built further to the west, on a north-south axis from the northern slopes of the Ālborz Mountains to the southern shore of the Caspian Sea. It receives its name from the nearby town of Tammīšeh, located immediately to the east of the Wall. Traveling west to east along the southern Caspian shoreline, the distance between the Alborz Mountains and the shore diminishes, so the location of the Wall is the most convenient one, as in this point the coastal plan has been reduced to a narrow corridor. It is slightly oriented on a N-NW axis because of the presence of a nearby river valley. In 1964, A. H. D. Bivar and G. Fehérvári were able to conduct excavations in this area before modern agricultural machinery was able to have much of an impact, and this helped immensely the survey, because in the 40 years in between the landscape has changed considerably. The fertile land and the humid climate make this one of the most productive agrarian landscapes in Iran, and the place has been heavily disturbed. On top of it, the bricks of the Wall have been robbed even more intensely than at Gorgān, and the humid climate has damaged remains other than brick or stone in a much more extensive way.

CORONA image of the northern terminal of the Tammīšeh Wall, with the remains of a fort submerged in an area of shallow water in the Caspian Sea (image taken from “Persia’s imperial power in Late Antiquity. The Great Wall of Gorgān and frontier landscapes of Sasanian Iran”, edited by Eberhard W. Sauer, Hamid Omrani Rekavandi, Tony J. Wilkinson and Jebrael Nokandeh).

The extension of the damage is such that archaeologists do not even know how wide it might have been. XIX c. travelers wrote that to them the wall looked like a succession of three ditches, but today the only remnants are a ditch and a land embankment to the east of it, suggesting that (contra intuitively) the ”enemy” side of the Wall was the western one, where the wide ditch might have acted like a moat. The embankment was 5.60-5.10 meters wide at the base, and 1.00-3.00 meters high, and 2.00-2.25 meters wide at the top. The surveyors think (although with a considerable degree of uncertainty) that this earthwork was probably flanked on both sides by walls of fired brick to protect it from erosion (given the rainy climate), and that it acted as a foundation for the Wall proper, which would have been built on top of it. This relies of the results from Bivar and Fehérvári’s 1964 dig: by chance, they found at the southern end of the Tammīšeh Wall the remains of a brick wall and a projecting tower of semi-elliptical plan built on top of the embankment. Due to the lack of remains elsewhere, this is the only real inkling at what the actual wall could have been like in Sasanian times.

Some more guesses can be made from comparisons with other Sasanian defensive walls. At the Darband wall (made of stone), the interval between the towers is of ca. 3.00-4.00 km. At the Ghilghilchay Wall (which is 50 km long in total, and made of mudbrick), the projecting towers are placed at variable 29-49 m intervals, with smaller projecting semi-circular protrusions that acted as buttresses located every 7.00-7.30 m; the wall was 4.10 m thick and the buttresses projected 5.20 m from its faces, on both sides. This can also serve as a guide for the Gorgān Wall, where few projecting towers have been found too.

The Tammīšeh Wall was built with fired bricks remarkably similar to the ones used in the Gorgān Wall (only slightly smaller, 38x38 cm instead of 40x40 cm), and actually these bricks are identical to the ones employed in the westernmost parts of the Gorgān wall. This suggests that both walls were built at the same time, and that probably the same teams that worked at the Tammīšeh Wall worked also in the western part of the Gorgān Wall. The construction of the Tammīšeh Wall was not uniform; in its southern part the wall climbs up a deep slope when it meets the Ālborz Mountains for a while before reaching its end. Here, building the earthwork as a foundation would not have been practical, but the moat was remained in front of the wall. When the Wall ends, it is followed by an earth bank that the surveyors believe may have been the aqueduct that fed the moat with water The survey team thought that as for the height of the wall, the earthwork at its base would have been 2.80 meters high at the very least and 4.00 m high maximum. As for the possible height of the upper wall, that is not possible to ascertain in situ due to the systematic robbing of its bricks. The only guess that can be made is again through comparison with other Sasanian walls, or through the accounts of XIX c. travelers or earlier Islamic accounts.

Still today, the parts still standing of the Darband Wall reach a height of 6 meters. In a report from 1580, the two parallel walls at Darband that go from the city to the sea would have been still 9 feet thick and 28-30 feet tall (i.e. 9.00 meters). Another report from 1770 stated that the walls still stood to a height of 9 meters. Another report of the XIX c. gives a height of 8-9.00 meters. This seems to be in agreement with the volume of the piles of rubble detected by Russian archaeologists under the Caspian Sea in the submerged part of the Darband wall. The current wall at Darband was built in the VI c. CE to replace an earlier one built of mudbrick between 439 and 450 CE, and which according to the descriptions of the ancients sources had a width of 8.00 m and a height of up to 16.00 m. The better-preserved parts of the Ghilghilchay Wall stand today to a height of 6.00-7.00 m. As an additional comparison, the earthen walls built in China during the IV c. CE survive to a height of 18 m. To the archaeologists of the GWS, it seems unlikely that the Gorgān Wall, built without foundations and without lime mortar, may have been higher than the Darband Wall, but the Tammīšeh Wall may have been higher.

Then there is the added matter of the submerged parts of both walls, and the possibility that they may have been joined back in the day of their construction due to the lower water level of the Caspian Sea. Underwater research under the Caspian in this area was complicated due to the murkiness of the water, but archaeologists were able to confirm the presence of a submerged fort under shallow waters where the Tammīšeh Wall reaches the current coastline, and that this Wall continues 700 meters following its same N-NW axis under the sea.

Old house at the village of Sarkālateh whose foundations have been built with bricks from the Tammīšeh Wall (image taken from “Persia’s imperial power in Late Antiquity. The Great Wall of Gorgān and frontier landscapes of Sasanian Iran”, edited by Eberhard W. Sauer, Hamid Omrani Rekavandi, Tony J. Wilkinson and Jebrael Nokandeh).