IMPERIAL STATE OF IRAN

Marā dād farmūd-o khod dāvar ast

THE POLITICS OF IRAN

A Prelude to the Royalist Restoration

A Prelude to the Royalist Restoration

The Politics of Iran

Shifting Political Sands: Growing Power of the Shah

Shifting Political Sands: Growing Power of the Shah

In modern Iran, the Office of the Prime Minister, the Cabinet and Parliament [Majlis] continue to serve as the established instrument of power and government. The latter instrument, the Parliament, functions without an effective party system. Concepts of left or right, democrats or monarchists have not taken root in Iran, where politics is akin to shifting desert sands as one faction or another seeks to advance its narrow interests.

The Iranian Parliament

Increasingly, however, amongst intellectual and popular circles alike, a strong Shah is viewed as a bulwark against factional turmoil. The prestige accrued to the monarchy in the wake of the Azerbaijan Crisis of 1946 had not only augmented the growing power of the Crown, but had forged an inextricable link between the Shah and the Army, an arm of the state that had its reputation tarnished by the aforementioned military debacle but now enjoyed something of a revitalisation, basking in the limelight alongside the Shah.

Prime Minister Razmara

The Rise and Fall of Prime Minister Razmara (1950 - 51)

All the King’s Men: The Shah’s Prime Minister

Thus it came as no surprise when on 26 June 1950 the Shah appointed the former military chief, General Ali Razmara, as Prime Minister. Unlike previous premiers, Razmara was not Moscow’s or London’s man in Tehran, nor was he beholden to a particular faction in the legislature. He was the Shah’s man. Razmara’s eminent military reputation did not, however, carry over into the political sphere. In Moscow he was criticised as being in the pay of the British and Americans, in London he was berated for his alleged communist sympathies, and, most importantly, in Tehran he was expected [by the various court factions] to both preserve the status quo as well as enact far-reaching reforms.

Funeral of Prime Minister Razmara

The divided Persian legislature could agree on one issue: the renegotiation of the country’s relationship with the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (A.I.O.C). Opposition to the company and its operations were echoed by all significant political groups. As such, Razmara’s support of a moderate solution allowed his domestic rivals to brand him as a traitor. Parliament rejected a profit-sharing proposal and convened the Assembly’s Special Oil Commission, chaired by Dr. Mosaddeq, which recommended nationalisation. Prime Minister Razmara challenged this recommendation with directness and vigor, dismissing the proposed nationalisation of the A.I.O.C as impracticable. For his staunch position against nationalisation, on 07 March 1951, Prime Minister Razmara was assassinated.

Prime Minister Mosaddeq

The Rise of Prime Minister Mosaddeq (1951 - 1953)

Home and Abroad: The Shah Eclipsed and the Shah Resplendent

Foreign Relations and the Nationalisation of the A.I.O.C (1951)

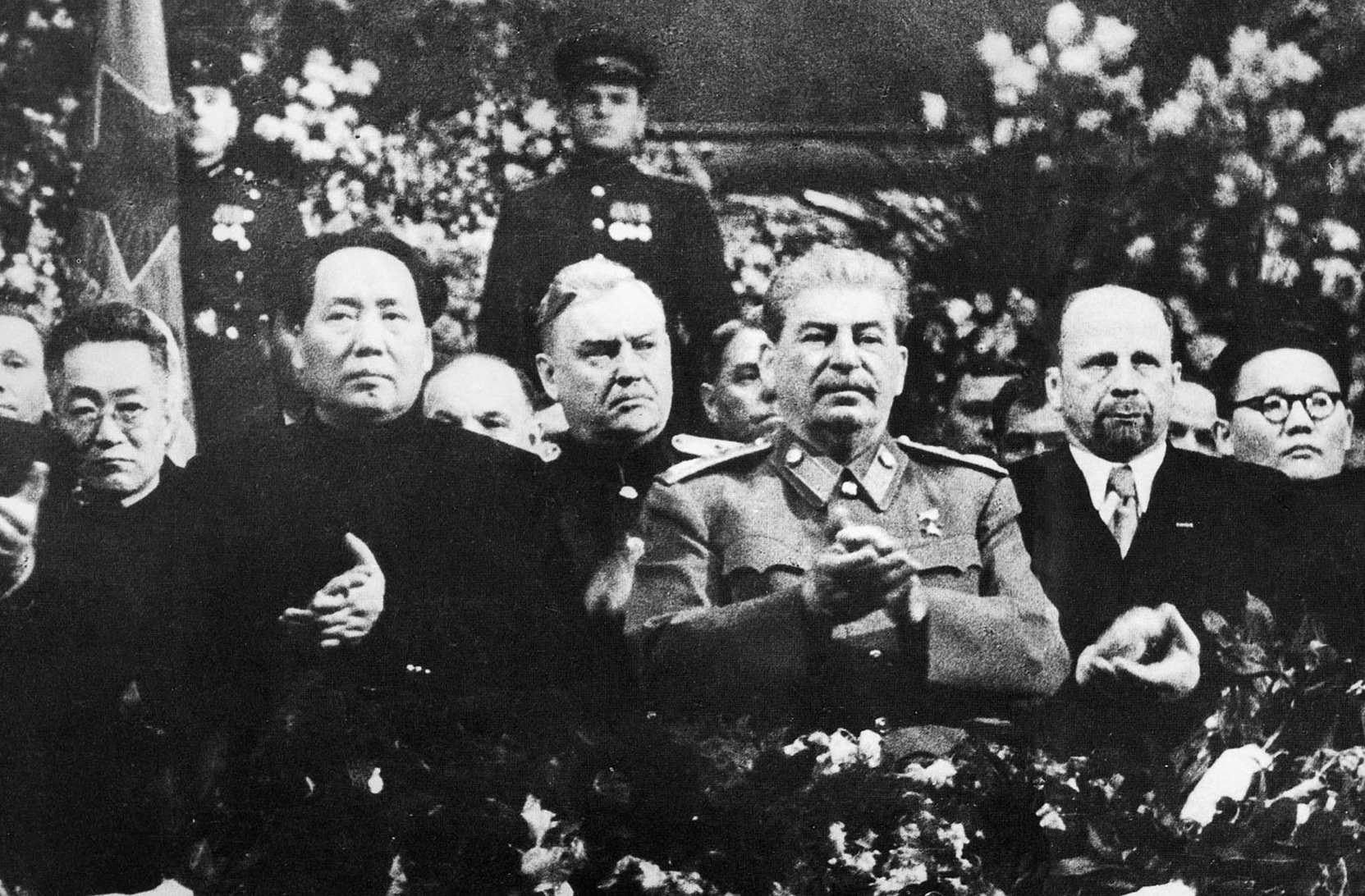

Notwithstanding his popularity at home, Mosaddeq’s perception abroad was hardly that of an eminent statesman. Unlike Nehru, India’s Harrow-educated parliamentarian, Mosaddeq was not well-regarded in London, and was viewed in some cases as a figure of fun. His excessive rhetoric has been seen as further evidence to the widely-held belief that Arabian passion often clouds pragmatism. Had Mosaddeq’s premiership been cast against a different tableau – that is, should it have transpired in a context other than the emerging Cold War – its comic elements would have taken pride of place. Nevertheless, the times are such that political deviations and experiments are inevitably cast within the milieu of cold calculation and constant mistrust that is part and parcel of the ongoing contest between East and West.

Prime Minister Mosaddeq announcing the nationalisation of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company

While Mosaddeq’s fervent nationalism has fallen upon receptive ears at home, it has earned an increasingly unfavourable reception in London as well as Washington. It was well known that Mosaddeq could not rely upon the Shah’s support in the eviction of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company. Nevertheless, the Prime Minister assumed that American petroleum interests would relish the opportunity to dislodge the British from their preeminent position in Iran. Although the United States voiced no objection when, on 01 May 1951, Prime Minister Mosaddeq announced the nationalisation of the A.I.O.C, the realities of the Cold War brought, by 1953, Washington more closely in line with London in opposing Mosaddeq.

The Bitter Quarrel with the Shah (1952)

It was one thing not to have the Shah as a friend, it was quite another to turn the monarch into an enemy. Yet, with tensions brewing between Tehran and London, this is precisely what Mossadeq opted to do when in 1952 he insisted that the power to appoint the Minister of War rested within the purview of the prime-ministerial office. The Shah, relying on the traditional dignity of his title and the enduring loyalty of the military corps, rejected Mosaddeq’s encroaching influence within the Armed Forces.

Pro-Mosaddeq Supporters rally in Tehran

Mosaddeq resigned in protest, accusing the Shah of violating the constitution. Violent riots ensued, and the Shah was forced to reinstate the wayward Prime Minister. In defiance and arrogance, Mosaddeq took the post of Minister of War for himself and set out to humble the Shah by launching a purge of the upper ranks of the officer corps and cutting the military budget by fifteen percent.

To the Victor Go the Spoils (1953)

A Triumphant Mosaddeq Celebrating the Nationalisation of the A.I.O.C

A Triumphant Mosaddeq Celebrating the Nationalisation of the A.I.O.C

Buoyed by popular support following the July 1953 Referendum, which accorded to the Prime Minister special extraordinary powers, Mosaddeq did not waver in his mission to humiliate the Shah. The Prime Minister nationalised the Shah’s private estates, reduced the funds allocated to the Royal Court, and brought royal charities under government surveillance. To add insult to injury, the Shah was prohibited from receiving diplomats, who would now conduct their business through the Foreign Ministry. The Shah’s glistening war medals and glowing international reputation did not prevent one British observer from commenting: “so much power is concentrated in the office of the Prime Minister and so little in the hands of the Shah.”