Collapse of the Müller Government

And Hindenburg's Appointee

The Müller Government oversaw a number of reforms to insurance, but such goodwill was quickly evaporated by the economic ruin beginning in 1929. Increased coverage in a time of a failing economy required an injection of taxpayer money, which rarely curries political favor. Furthermore, the governing coalition fractured in disagreements over how precisely to raise the funds; though Müller himself was ready to concede to Heinrich Brüning's centrist compromise, the parliamentary Social Democrats vetoed such measures.

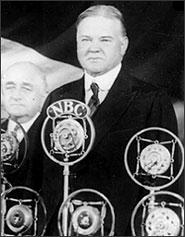

No doubt contributing to the decline of this coordination was the unfortunate health of Müller, whose very life was threatened by illness for several months throughout 1929. Communication broke down and he lacked the status and backing to wrangle the chaotic happenings of Weimar politics. Perhaps more importantly, Müller lacked a relationship with President von Hindenburg, who had already prepared to distance himself closer to the right.

Through the authority of the presidential office, Hindenburg could have secured for Müller the ability to enforce his plans, maintaining some sense of stability at the expense of democracy. At the behest of his advisers and of his own thoughts, Hindenburg denied Müller this support. Without any other recourse, Müller was forced to resign March 27, 1930.

Already, President von Hindenburg and his cabal of advisers had prepared for this inevitability. As early as August 1929, Heinrich Brüning had been approached by Kurt von Schleicher, a military man who wielded the immense influence of the army and Hindenburg. By his own hand, von Schleicher had helped organize a number of intrigues that accelerated the implosion of the Müller Government. Brüning was contacted numerous times before the fall of Müller, with the plan being that Müller would be discarded after becoming essentially the fall man in instituting the unpopular Young Plan.

President von Hindenburg himself had not spoken to Brüning until February 1930, at the recommendation of von Schleicher. Hindenburg was impressed, chiefly by Brüning's experience as a machine gun officer. More practically, Brüning held sway among centrists, especially within his own party of Zentrum, and was a trained economist. Brüning offered solutions to the immediate problems of Germany, namely those of economic importance, speaking on the necessity of liberating the nation from the intense burdens imposed by foreign nations as well as balancing the disastrous budget left by Müller.

Only two days following the resignation of Müller, President von Hindenburg appointed Heinrich Brüning as chancellor. Tasked with the unenviable hardship of lifting Germany from its languish, at a period of intense political polarization, Brüning prepared to propose his policies to a hostile parliament, while Hindenburg and his advisers readied themselves to implement a system that would shore up their ideal state.