A Brief History of Zunism

Before the advent of Islam in Afghanistan, people followed different religions, some widely known like Zoroastrianism, Hinduism, and Buddhism, while others not so well known but were locally very popular and zealously followed. One such indigenous religion, with a large following in Zabulistan during the 7th to 9th centuries, was the cult of Žun.

Xuanzang, the famous Chinese Buddhist pilgrim, had visited Zabul in 644, who described, in Da Tang Xiu Jee, the shrine of Suna or Zhuna in some detail, but he neither mentioned its origin nor the identity of its followers:

The Coming of Islam

Arab Muslims appeared in Sistan in 652-53CE as part of the last stage of claiming Iran and after the death of Yazdagird III, the last Sassanid king in 651. A year later, the Arab forces advanced against the Hindu Kush and the lands of Zabulistan and Kabulistan. The new Arab Governor of Sistan, 'Abd al-Rahman bin Samurah launched an offensive against these rulers and reduced both kingdoms during 664-65. He surrounded the holy mountain on which the temple of Zun was located. He “went into the temple of Zur (Žun), an idol of gold with two rubies for eyes, he cut off a hand and took out the rubies. Then he said to the Satrap, ‘keep the gold and gems. I only wanted to show that it had no power to harm or help.’”. However, Abd al-Rahman was relieved of his governorship in 666 which led to the loss of these kingdoms as quickly as they had been captured.

Barha Tegin appears in history following the capture of Kabul by the Arabs under Abd al-Rahman circa 665 CE. The ruler of Kabul at that time was Ghar-ilchi of the Nezak Huns. The Arab conquest mortally weakened the Nezak Dynasty. The Shahis under Barha Tegin, who were already ruling in Zabulistan, were then able to take control of Kabulistan. Some authors attribute the rise of Barha Tegin precisely to the weakening of the last Nezak Hun ruler Ghar-ilchi, after the successful Arab invasion under Abd al-Rahman ibn Samura. Around the time the first ruler of the Turk Shahis Barha Tegin died, his dynasty split into two kingdoms. From 680 AD, Tegin Shah became the king of the Turk Shahis, and ruled the area from Kabulistan to Gandhara. His title was "Khorasan Tegin Shah" (meaning "Tegin, King of the East"), and he was known in Chinese sources as Wusan Teqin Sa. His grand title probably refers to his resistance to the peril of the Umayyad caliph from the west.

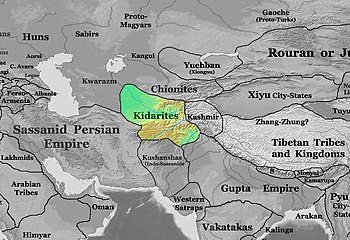

The ruler of Zabulistan split from his brother, the Shahi of Kabul, and established the Zunbil dynasty. The title Zunbil can be traced back to the Middle-Persian original Zūn-dātbar, 'Zun the Justice-giver'. The geographical name Zamindawar would also reflect this, from Middle Persian 'Zamin-i dātbar' (Land of the Justice-giver). This dynasty, Rutbil or Ratbil in the Arab literature, became famous for their tenacious resistance to the Arab advance towards the east and northwards to Kabul. Both the rulers and their dynasties, which survived for about two centuries, were considered by the Arabs as Turkish. However, the opinion of modern scholars greatly differs with regard to their origin and identity, with some positing them to be of Kidarite or Hepthalite origin.

The petty kingdom of Zabulistan bordered Kabulistan in the northeast and in the south and west it included areas of al-Rukhkhaj, the modern Kandahar region, Zamindawar and area up to Bost on the confluence of Arghandab and Helmand rivers. The Sulaiman Mountains formed the eastern border. Ghazni was the winter capital of the kingdom while Zamindawar was the summer capital and religious and pilgrimage centre devoted to Žun.

The relationship between the two related families of Kabul and Zabul was at times antagonistic, but they fought together against Arab incursions. In 698 Ubayd Allah ibn Abi Bakra, governor of Sijistan and a military commander of the Umayyad Caliphate, led an 'Army of Destruction' against the Zunbils. He was defeated and was forced to offer a large tribute, give hostages including three of his sons, and take an oath not to invade the territory of the Zunbils again.

About 700, Al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf appointed Ibn al-Ash'ath as commander of a huge Iraqi army, the so-called "Peacock Army", to subdue the troublesome principality of Zabulistan. During the campaign, al-Hajjaj's overbearing behaviour caused Ibn al-Ash'ath and the army to rebel. After patching up an agreement with the Zunbils, the army started on its march back to Iraq. On the way, a mutiny against al-Hajjaj developed into a full-fledged anti-Umayyad rebellion.

The Arabs regularly claimed nominal overlordship over the Zunbils, and in 711 Qutayba ibn Muslim managed to force them to pay tribute. In 725–726, Yazid ibn al-Ghurayf, governor of Sistan failed to do so. The Arabs would not be able to again obtain tribute from the Zunbils until 769 CE, when Ma'n b. Za'ida al-Shaybanl defeated them near Ghazni.

Arabic sources recount that, after the Abbasids came to power in 750, the Zunbils made submissions to the third Abbasid Caliph al-Mahdi (r. 775–785), but these appear to have been nominal acts, and the people of the region continued to resist Muslim rule. The Muslim historian Ya'qubi in his Ta'rikh ("History"), recounts that al-Mahdi asked for, and apparently obtained, the submission of various Central Asian rulers, including that of the Zunbils.

Arab campaigns of destruction are documented around 795 CE, as the Muslim writer Kitāb al-buldān records the destruction of a Šāh Bahār (“Temple of the King”), though to be Tepe Sardar, at that time: he recounts that the Arabs attacked the Šāh Bahār, "in which were idols worshipped by the people. They destroyed and burnt them"

Current Era – 867CE

Zabulistan has been reduced to a rump state after repeated attacks by the Arabs with a distinct Hepthalite identity, though there has been some assimilation with the local Iranian populations. Firoz is the current Zunbil but is facing a grave threat – the ascendant Saffarids and their Amir-e Amiran Ya’qub al-Laith. Already, his cousin Hurmiz has bent the knee and surrendered Bost and Firuz is scrambling to pull together the native tribes of Pamiris, Afghanis and Turco-Hepthalites to defend the old ways against the wave of Islamification.

Before the advent of Islam in Afghanistan, people followed different religions, some widely known like Zoroastrianism, Hinduism, and Buddhism, while others not so well known but were locally very popular and zealously followed. One such indigenous religion, with a large following in Zabulistan during the 7th to 9th centuries, was the cult of Žun.

Xuanzang, the famous Chinese Buddhist pilgrim, had visited Zabul in 644, who described, in Da Tang Xiu Jee, the shrine of Suna or Zhuna in some detail, but he neither mentioned its origin nor the identity of its followers:

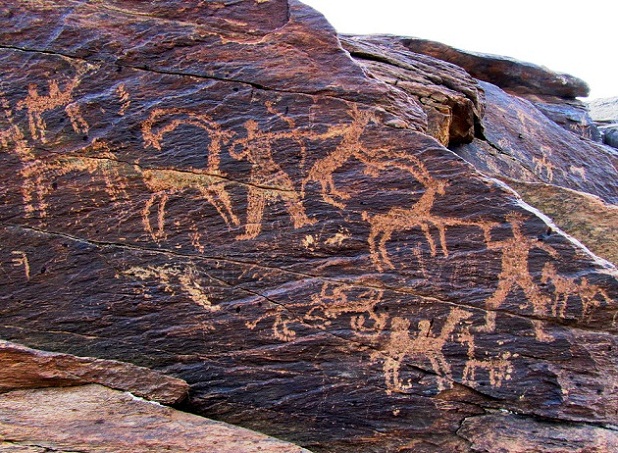

As a custom of this country, people worship a deity of dubious character. On Mount Congling is its statue called Zhun. The ceremonial institution is extremely gorgeous. The shrine is roofed with both gold and silver plates and paved with silver on the floor. More than one thousand people visit this shrine everyday. In front of the shrine is a back bone of fish. At the center is a hole through which a mounted horseman can pass freely.

According to local tradition, the deity Zhuna first came from far to this mountain desiring to dwell on it, but the original deity of the mountain trembled with anger and shook the valleys. Zhuna said, "As having no wish to live together, you might be thus trembling. If you only entertained me as a guest, I would confer on you great riches and treasure. Now I go to Mount Zhunahira in Zabul. Whenever the king and his ministers may offer me their tributes every year, then you shall stand face to face with me"

There are several dozen 'deva' temples, and the sectarians of various denominations dwell together. Among those counted, the Tirthakas are many in number and very powerful. They follow Zhuna). In the past this deva came from Mount Aruna of Kapisi to live on Mount Zhunahira on the southern border of this country. He showed dignity and gave the people happiness, or perpetrated violence and evil. Those who believed in this deity attained their wishes, whereas those who looked down on him received misfortune. Therefore all people, both from far and near, worshipped him; and all people, both from the upper and lower classes, held him in reverence. People from neighbouring countries and of different manners and customs, kings and courtiers assemble together every year on an auspicious day of that year, and sincerely devote themselves by presenting gold and silver as well as rare treasures, or by competitively dedicating cattle and horses as well as domestic animals. Accordingly, the floors were full of gold and silver, while the valleys were full of sheep and horses. Nobody has any intention to steal them, but solely tries to offer such objects. The heretics who intently serve the deva practice asceticism, and then the deva gives them magical power in return. The heretics effectively perform magic to treat illness, by which many recover completely.

The Coming of Islam

Arab Muslims appeared in Sistan in 652-53CE as part of the last stage of claiming Iran and after the death of Yazdagird III, the last Sassanid king in 651. A year later, the Arab forces advanced against the Hindu Kush and the lands of Zabulistan and Kabulistan. The new Arab Governor of Sistan, 'Abd al-Rahman bin Samurah launched an offensive against these rulers and reduced both kingdoms during 664-65. He surrounded the holy mountain on which the temple of Zun was located. He “went into the temple of Zur (Žun), an idol of gold with two rubies for eyes, he cut off a hand and took out the rubies. Then he said to the Satrap, ‘keep the gold and gems. I only wanted to show that it had no power to harm or help.’”. However, Abd al-Rahman was relieved of his governorship in 666 which led to the loss of these kingdoms as quickly as they had been captured.

Barha Tegin appears in history following the capture of Kabul by the Arabs under Abd al-Rahman circa 665 CE. The ruler of Kabul at that time was Ghar-ilchi of the Nezak Huns. The Arab conquest mortally weakened the Nezak Dynasty. The Shahis under Barha Tegin, who were already ruling in Zabulistan, were then able to take control of Kabulistan. Some authors attribute the rise of Barha Tegin precisely to the weakening of the last Nezak Hun ruler Ghar-ilchi, after the successful Arab invasion under Abd al-Rahman ibn Samura. Around the time the first ruler of the Turk Shahis Barha Tegin died, his dynasty split into two kingdoms. From 680 AD, Tegin Shah became the king of the Turk Shahis, and ruled the area from Kabulistan to Gandhara. His title was "Khorasan Tegin Shah" (meaning "Tegin, King of the East"), and he was known in Chinese sources as Wusan Teqin Sa. His grand title probably refers to his resistance to the peril of the Umayyad caliph from the west.

The ruler of Zabulistan split from his brother, the Shahi of Kabul, and established the Zunbil dynasty. The title Zunbil can be traced back to the Middle-Persian original Zūn-dātbar, 'Zun the Justice-giver'. The geographical name Zamindawar would also reflect this, from Middle Persian 'Zamin-i dātbar' (Land of the Justice-giver). This dynasty, Rutbil or Ratbil in the Arab literature, became famous for their tenacious resistance to the Arab advance towards the east and northwards to Kabul. Both the rulers and their dynasties, which survived for about two centuries, were considered by the Arabs as Turkish. However, the opinion of modern scholars greatly differs with regard to their origin and identity, with some positing them to be of Kidarite or Hepthalite origin.

The petty kingdom of Zabulistan bordered Kabulistan in the northeast and in the south and west it included areas of al-Rukhkhaj, the modern Kandahar region, Zamindawar and area up to Bost on the confluence of Arghandab and Helmand rivers. The Sulaiman Mountains formed the eastern border. Ghazni was the winter capital of the kingdom while Zamindawar was the summer capital and religious and pilgrimage centre devoted to Žun.

The relationship between the two related families of Kabul and Zabul was at times antagonistic, but they fought together against Arab incursions. In 698 Ubayd Allah ibn Abi Bakra, governor of Sijistan and a military commander of the Umayyad Caliphate, led an 'Army of Destruction' against the Zunbils. He was defeated and was forced to offer a large tribute, give hostages including three of his sons, and take an oath not to invade the territory of the Zunbils again.

About 700, Al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf appointed Ibn al-Ash'ath as commander of a huge Iraqi army, the so-called "Peacock Army", to subdue the troublesome principality of Zabulistan. During the campaign, al-Hajjaj's overbearing behaviour caused Ibn al-Ash'ath and the army to rebel. After patching up an agreement with the Zunbils, the army started on its march back to Iraq. On the way, a mutiny against al-Hajjaj developed into a full-fledged anti-Umayyad rebellion.

The Arabs regularly claimed nominal overlordship over the Zunbils, and in 711 Qutayba ibn Muslim managed to force them to pay tribute. In 725–726, Yazid ibn al-Ghurayf, governor of Sistan failed to do so. The Arabs would not be able to again obtain tribute from the Zunbils until 769 CE, when Ma'n b. Za'ida al-Shaybanl defeated them near Ghazni.

Arabic sources recount that, after the Abbasids came to power in 750, the Zunbils made submissions to the third Abbasid Caliph al-Mahdi (r. 775–785), but these appear to have been nominal acts, and the people of the region continued to resist Muslim rule. The Muslim historian Ya'qubi in his Ta'rikh ("History"), recounts that al-Mahdi asked for, and apparently obtained, the submission of various Central Asian rulers, including that of the Zunbils.

Arab campaigns of destruction are documented around 795 CE, as the Muslim writer Kitāb al-buldān records the destruction of a Šāh Bahār (“Temple of the King”), though to be Tepe Sardar, at that time: he recounts that the Arabs attacked the Šāh Bahār, "in which were idols worshipped by the people. They destroyed and burnt them"

Current Era – 867CE

Zabulistan has been reduced to a rump state after repeated attacks by the Arabs with a distinct Hepthalite identity, though there has been some assimilation with the local Iranian populations. Firoz is the current Zunbil but is facing a grave threat – the ascendant Saffarids and their Amir-e Amiran Ya’qub al-Laith. Already, his cousin Hurmiz has bent the knee and surrendered Bost and Firuz is scrambling to pull together the native tribes of Pamiris, Afghanis and Turco-Hepthalites to defend the old ways against the wave of Islamification.

Last edited:

- 4

- 1